3. Where Impunity Thrives

A climate of impunity reached a tragic culmination on November 23, 2009, when gunmen ambushed a caravan escorting political candidate Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu as he prepared to file papers to become a candidate for provincial governor in the Philippines. The attackers slaughtered 58 people, among them 30 journalists and two media workers, the largest toll of journalists murdered in a single act since CPJ began keeping track in 1992.

The mass killing on the outskirts of Ampatuan Town provoked immense outrage. But no one has been convicted of playing any role in the massacre, and few are surprised. Many saw the attack as a natural result of the Philippines’ long-running mix of powerful, armed groups, government corruption and inaction, and weak law enforcement. This cycle of violence and impunity shows no sign of weakening.

The Road to Justice

• Table of Contents

• Sidebar: Estemirova

Multimedia

• Slideshow

In print

• Download a pdf

In other languages

• Español

• Français

• Português

• العربية

• Русский

More than 50 journalists were murdered, without justice, for their work in the Philippines between 2004 and 2013. Hundreds more human rights defenders, activists, and politicians have become victims of extrajudicial killings, mostly without consequence for the assailants. And in this, the Philippines is not alone.

Journalist murders are rarely isolated events. They are not usually the spontaneous act of a hothead angered by what he reads in the newspaper. All too often they are premeditated—ordered, paid for, and orchestrated. They fit into two overarching patterns: intimidation against those who reveal corruption, expose political and financial misconduct, or report on crime; and circumstances where everyday violence by militant groups or organized crime obstructs justice. Enabling these patterns is the simple fact that murdering a journalist is easy to get away with. According to CPJ research, there are no consequences for the killers of journalists in nearly nine out of 10 cases.

A culture of impunity in killings of journalists is self-fueling. Where justice fails, violence often repeats, according to trends documented over the last seven years by CPJ’s Global Impunity Index. Iraq, for example, has by far the largest number of unsolved murders and recorded nine new targeted killings of journalists in 2013. Russia saw two more journalists murdered last year, bringing to 14 its total of journalism-related killings with full impunity since 2004. In Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, and India, a total of seven journalists were murdered in 2013. All but one of the countries where murders of journalists took place in 2013 had records of impunity in four or more earlier killings. “Every act of violence committed against a journalist that goes uninvestigated and unpunished is an open invitation for further violence,” then-United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said earlier this year at a Human Rights Council meeting.

There are many ways that widespread, enduring impunity takes hold when it comes to attacks on journalists. In some cases, it is a lack of political will. In others, conflict or weak law enforcement keeps justice at bay. In most situations, it is a combination of these factors. Examining the environments in which impunity thrives is the first step to ending it.

Governments often complain that justice is out of their hands. Impunity in journalist killings is the tip of the iceberg, their argument goes, and immense systemic problems from widespread corruption to continuing strife are the real issues. It is true that insecure or dysfunctional environments seed impunity, but CPJ has seen repeatedly that lack of political will to prosecute is the most prevalent factor behind the alarming numbers of unsolved cases. States too often show that they are unwilling, not simply unable, to pursue justice when it comes to journalist killings. “The most important element is political will,” said Frank LaRue, the former U.N. special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

CPJ has documented case after case that fails to advance toward justice despite evidence that points to potential culprits. In others, law enforcement officials have failed to follow leads, interview witnesses, collect sufficient evidence, or pursue complete prosecutions. When a prominent Sri Lankan newspaper editor, Lasantha Wickramatunga, was assassinated in 2009, his attackers beat him with iron bars and wooden poles on a busy street, within sight of soldiers at an airbase. According to his widow, Sonali Samarasinghe, the police made little use of witnesses and reported Wickramatunga’s death as a shooting, contradicting medical reports that did not mention any bullet wounds. These were but two of several complaints and questions raised in an investigation that, despite pledges from President Mahinda Rajapaksa to solve the crime, has passed its fifth anniversary without a trial.

Evidence in this and other cases frequently suggests the perpetrators are top officials in a country’s power structure. CPJ data analyzing cases since 1992 show that state actors or government or military officials are suspected of being responsible for more than 30 percent of journalists’ murders. In hundreds of other cases, political groups or individuals who wield strong economic and political influence are the suspected killers. Against this reality, it is not surprising that justice is so often nipped in the bud.

“Journalists may become victims of political vendettas or are targeted by politicians. Local-level politicians may also have business interests that journalists write about or report on,” said Geeta Seshu, consulting editor of The Hoot, a media watchdog in India, where seven journalists have been murdered with complete impunity in the last decade. “Political party members who target journalists are protected by their parties and can exercise great influence on the local administration or police so as to delay or hamper investigation.”

In the Gambia, after the 2004 murder of Deyda Hydara, a respected editor and columnist known for his criticism of President Yahya Jammeh, authorities did not interview at least two key witnesses who were injured with Hydara in the attack, nor did they conduct basic ballistics tests—failings recently acknowledged by the regional court of the Economic Community of West African States. The court ruled in June 2014 that the Gambia did not conduct a meaningful investigation into Hydara’s murder, in part because the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), itself a suspect, conducted the investigation. “How can the NIA do an investigation when they are one of the suspects?” said Rupert Skilbeck, litigation director at the Open Society Institute Justice Initiative, who worked with lawyers to bring the case to the regional court.

Worldwide, there has been a near-total failure to prosecute those who order crimes against journalists. In only 2 percent of cases of journalists murdered for their work from 2004 through 2013 was complete justice achieved. In most, there was no justice whatsoever, or convictions targeted lower-level accomplices and triggermen but not the masterminds. Case in point: In the high-profile trial in the murder of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, even a mention of the suspected mastermind has been kept out of the courtroom; closed-door proceedings were ordered for another high-level suspect who might have revealed his identity.

Last year’s conviction of the killer of popular Philippine radio journalist Gerardo Ortega was a victory for justice. But it was also a stark reminder that two suspects, Joel Reyes and Mario Reyes, brothers and both powerful local politicians whom Ortega had accused of corruption, were yet to be even apprehended despite implicating testimony from the convicted gunman. In a statement that echoes the sentiments of dozens of other family members of killed journalists, Michaella Ortega, Gerardo Ortega’s daughter, appealed to authorities to pursue full justice against those with “the power, the money, and the motive to have my father killed.”

The Ortega family’s partial victory typifies the one in 10 cases in which there is some measure of justice. Nearly all of the successful prosecutions are the result of intense international and local pressure, media attention, dogged pursuit from family members, parallel investigations by colleagues, or legal challenges by civil society groups. When pressed from all sides, states do respond, proving that where there is political will, there is a way.

If lack of political will is justice’s first adversary, conflict is not far behind. The various forms of conflict—sectarian strife, political insurgencies or combat as defined in international law—are backdrops to some of the most entrenched climates of impunity. Journalists operating in these environments are exposed to immense physical risk. Many are injured or killed by crossfire or by terrorist acts in the course of day-to-day assignments. Even amid these dangers, however, targeted murder is the No. 1 reason journalists are killed. More than 95 percent of those targeted are local reporters, most of them covering politics, corruption, war or crime at the time of their murders.

For the last five years, Iraq and Somalia have held the top two spots in CPJ’s Impunity Index, with a combined total of 127 cases of journalists murdered, more than twice the number killed in crossfire and dangerous assignments. Syria, one of the few countries where crossfire deaths of journalists outnumber murders, shows signs of following suit. It joined CPJ’s Global Impunity Index for the first time in 2014 with seven cases of targeted murder—a number that has since grown with the shocking beheadings of U.S. freelance journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff by the Islamic State militant group. The rate of total impunity for these three countries combined is 99 percent.

Armed sectarian groups waged the majority of these attacks. The Al-Qaeda splinter group Islamic State and other Sunni militant groups are believed responsible for a few of the targeted murders of nine journalists last year in Iraq, according to CPJ research. In earlier years of high violence there, Iraqi journalists were similarly targeted by Sunni and Shiite groups. In Somalia, Al-Shabaab militants for years have threatened and assaulted journalists over coverage of the group’s activities. With this fact comes a crucial question: When states are at war with the perpetrators of anti-press violence, can the states be blamed for not prosecuting them?

Some say the answer is no. “Somalia has been in conflicts since 1991 and the country is still at war with extremists,” said Abdirahman Omar Osman, senior media and strategic communications adviser to Somalia’s government. “Somalia faces challenges such as lack of resources, lack of functioning institutions, lack of security as Al-Shabaab is fighting with the government, lack of good governance, and much more.”

Yet media colleagues are frustrated by what they see as complete inaction. “The police do nothing after the journalist is killed,” said Abukar Albadri, director of the Somali media company Badri Media Productions. “If the government wants to prosecute killers of the journalists it would make all its pledges functional. It pledged to form a task force that would investigate the murders of the journalists; it didn’t work. It pledged to investigate and bring the culprits to justice; there is no investigation made on any case so far.”

The inaction is particularly stark in cases when suspicion points to government officials themselves, and to other culprits not shielded by the might and facelessness that armed groups can provide. In the northern Iraqi city of Kirkuk, for example, assailants shot freelance writer Soran Mama Hama in 2008 shortly after he had exposed police complicity in the local prostitution trade. Despite pledges to CPJ from local authorities to give the case full attention, no arrests have been reported.

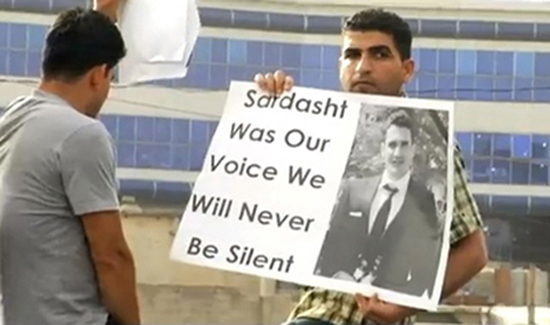

In a special report on impunity in Iraqi Kurdistan, CPJ examined other cases, including the 2010 killing of Sardasht Osman, a student journalist widely popular for his articles about corruption involving high-ranking government officials. Osman was abducted and found dead two days later. Kurdistan’s security forces attributed the murder to a group affiliated with Al-Qaeda, but relatives and colleagues found this account implausible. Seventy-five Kurdish journalists, editors and intellectuals blamed the government. “We believe the Kurdistan Regional Government and its security forces are responsible first and foremost, and they are supposed to do everything in order to find this evil hand,” they said in a statement at the time.

In Nigeria, where five journalists have been murdered with impunity in the last decade, a similar dynamic is in play—though with lower overall levels of violence. In response to CPJ’s 2013 Global Impunity Index, a spokesman for President Goodluck Jonathan blamed the crossfire of the extremist group Boko Haram for journalist deaths. Boko Haram clearly is responsible for many journalist fatalities in Nigeria. But killings have not been investigated in cases like that of the editor Bayo Ohu, who was shot at his front door by six unidentified assailants in retaliation, colleagues believe, for his reporting on local politics.

Boko Haram’s terror also does not offer an explanation for why the 2006 shooting of award-winning journalist Godwin Agbroko was never fully investigated. Agbroko was found dead in his car, with a single bullet in his neck, his valuables untouched. The police initially said the crime appeared to be an armed robbery, but later suggested it could be an assassination; there have been no developments since. Agbroko’s family still struggles for answers eight years later. “It was all shrouded in uncertainty and there was no procedure for investigation,” the journalist’s daughter Teja Agbroko Omisore told CPJ. “Nothing was open. Nothing was done.”

During his first state of the nation address in 2011, Philippine President Benigno Aquino III pledged that his administration would work to end impunity and bring an era of “swift justice.” His words were welcomed by colleagues and families of the victims of the 2009 Maguindanao Massacre, who have been seeking resolution and solace after the killings of 58 people, 32 members of the press among them. But justice has not been swift.

At the start of the Maguindanao case, few observers expected a quick prosecution. With 58 victims, and more than 180 suspects, even the most efficient system would be hard-pressed to dispatch justice quickly. Nevertheless, as the fifth anniversary of this heinous crime nears with no convictions in sight, the slow pace of justice has many worried that justice will be unbearably protracted or severely compromised, or both.

The trial of the Maguindanao massacre has been described by President Aquino as a “litmus test” for justice in the Philippines, a chance to show that the oldest democracy in Asia has a threshold for how much impunity it will tolerate. Instead, the proceedings have underlined the country’s failings.

Countries where CPJ has recorded high rates of anti-press violence and impunity, such as the Philippines, often suffer from weak investigative and prosecutorial capacities, or find their justice system has been co-opted by corruption and violent intimidation. The events of the massacre reflect this pattern of impunity—a flawed investigation, privileges for some suspects in detention, poor witness solicitation and protection, and delaying tactics of the defense—according to Prima Jesusa Quinsayas, a lawyer working for the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists. Quinsayas is also a private prosecutor representing many of the victims’ families. In the Philippines justice system, private prosecutors may work alongside the state prosecution team.

The evidence collected is widely thought to be flawed. Local press groups conducted a fact-finding mission immediately after the killings and found the area surrounding the crime scene was not cordoned off. Recovery teams used a backhoe rather than shovels to raise the buried victims, a method that might have destroyed forensic evidence. Personal effects of victims, including mobile phone SIM cards, had not been collected. “The case would collapse if you rely on evidence,” said Jose Pablo Baraybar, executive director of Equipo Peruano de Antropologia Forense, a Peruvian-based NGO invited to look at the crime scene. Dozens of suspects have not yet been apprehended.

Because of these shortcomings, witness testimony has been paramount to the case. But in a series of violent setbacks, three important witnesses were killed. One, Esmael Amil Enog, was found hacked to pieces and stuffed into a bag. Enog, a driver hired the day of the massacre, had offered direct testimony identifying many of the armed men. Two relatives of witnesses were killed and a third was injured after being shot multiple times. The loss of witnesses has brought scrutiny of the Philippines Witness Protection Program, considered heavily under-resourced. Quinsayas said she has been asked to escort witnesses herself to trial motions, in lieu of state protection. Mary Grave Morales, whose husband and sister, both journalists, were among the 2009 Ampatuan victims, told CPJ last year, “When all of those who witnessed the crimes are also dead, the trial will be useless. Justice will not be served.”

The defendants, several of them high-ranking members of the powerful and wealthy Ampatuan clan, have extensive resources to forestall justice. Some families of the victims, many coping with the loss their breadwinner, say they have been approached with bribes and threats. The defense mobilized by the accused, meanwhile, has prolonged the case for years with legal tactics, exploiting rules of the court that many feel need reform in the Philippines. In other cases, notably the murders of the popular whistle-blowing journalists Marlene Esperat and Gerardo Ortega, this kind of maneuvering has bought time and opportunity to allow the masterminds to wrangle a way out of a trial. For witnesses and victims’ family members, every year added to the trial is another year to live under intense psychological and financial strain or fear.

But they also are wary of a contradictory threat: that the state may be acting in too much haste. In February 2014, the prosecution told the court it was “no longer inclined” to present more evidence against the 28 defendants who have been arraigned, and was ready to rest its case against them. On the one hand, this would move cases against these suspects, including Andal Ampatuan Jr., accused of leading the attack, from bail hearings to criminal trial. But it also would limit the range of admitted evidence. “I worry that in the guise of speedy justice, what we get instead is compromised justice,” said Quinsayas.

Deficiencies in law and order help perpetrators elude justice in other countries where journalists are targeted, among them Pakistan, Nigeria, and Honduras. In Mexico, widespread corruption among law enforcement, the judiciary, and the political system has resulted in only the most perfunctory investigations into dozens of cases where journalists have been murdered or gone missing while covering the criminal activities of drug cartels. The use of violence to eliminate or intimidate anyone who stands in the way of impunity is also in play in Mexico, seventh in the world for unsolved journalist cases according to CPJ’s Global Impunity Index. In one disconcerting case, both the lead federal investigator and his replacement working on the murder of the veteran crime reporter Armando Rodríguez Carreón were murdered. Gunmen shot Rodríguez in his car in front of his 8-year-old daughter in November 2008.

The battle to address these systemic problems is not a small one, but strategies have emerged. Mexico recently adopted legislation allowing federal authorities to investigate attacks against journalists instead of local police, more likely to be complicit or influenced by the criminal groups that dominate their areas. In the Philippines, freedom of expression organizations jointly presented recommendations to the Department of Justice in 2010. They include: strengthening the Witness Protection Program; forming response teams with government, media, and NGO representation that investigate journalists’ murders; and revising court rules that, in the words of Melinda Quintos De Jesus, director of the Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility, “scrape off the age-old barnacles of a judicial system that seems to exist only for the benefit of lawyers.”

It will take time for such steps, even if fully adopted and implemented, to make a difference. In the interim, international and local vigilance over the Maguindanao trial must be sustained, said Prima Quinsayas, who added: “To lose it in the public radar is to be defeated by the protracted proceedings, which is one of the characteristics of the culture of impunity in the Philippines.”

Few countries have more ingredients than Pakistan to make a climate of impunity. The nation and its media suffer habitual violence waged by well-armed militant extremists and political groups, along with criminal organizations. Its politics are turbulent and its judicial institutions weak. With a history of contentiousness between media and government, political will can easily be questioned. Deadly and injurious assaults against media are frequent. At least 23 journalists were murdered between 2004 and 2013. Until this year, Pakistan had a perfect record of impunity in these cases.

Then came the news in early March 2014 that the Kandhkot Anti-Terrorism Court convicted six suspects of the murder of the popular television broadcaster Wali Khan Babar. Babar, a news presenter for Geo TV, was assassinated on his way home from work in Karachi on January 13, 2011. Four men were sentenced to life; two others, whom police have not apprehended, were sentenced to death in absentia. But justice is far from complete. In addition to the two suspects who remain at large, no one has been prosecuted for ordering the crime. Although the case represents a victory of sorts for Pakistani journalists, it is a somber one. “All the same, we’d rather not be congratulated for losing a journalist,” Shahrukh Hasan, managing director of the Jang Group, which owns Geo TV, told CPJ during a visit to the station in March of this year.

The full motives behind Babar’s killing have not been revealed, but several suspects convicted in Khan’s murder are linked to the Muttahida Qaumi Movement, a political party that wields immense power in Karachi. In a CPJ special report in 2013, journalist Elizabeth Rubin examined impunity in Pakistan’s violence against the news media, including this case, concluding that Babar’s work for Geo had put him at odds with the party.

Babar’s killers went to unthinkable lengths to protect themselves, and the path to justice has been a shockingly bloody one. In the three years that passed between killing and conviction, at least five people connected to the investigation and prosecution of the crime were themselves murdered. They included an informant, found dead in a sack within two weeks of the murder, two policemen who worked on the case, the brother of a local police chief possibly targeted as a warning, and an eyewitness, shot days before he was due to testify. Two prosecutors who worked on the case were driven into exile with threats.

At some point, the case caught the attention of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who took office after general elections in 2013. Sindh province’s home secretary recalled in a meeting with CPJ that the prime minister began making calls to check on the case’s progress. In September 2013, Pakistan’s then-Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry excoriated Karachi law enforcement agencies in a hearing, demanding a report on their failures in the Babar case. All the while, Geo TV, at that time one of the country’s largest and most popular stations, kept a heavy media spotlight on the case.

Pakistan’s press freedom groups campaigned vigorously for the cases of Babar and dozens of other journalists killed in the line of duty. International attention also mounted. In early 2013, the United Nations began to implement its interagency Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, which named Pakistan as a focus country. The plan, drafted by UNESCO, calls on states to take steps to improve investigations and prosecutions in cases of journalist murders and, among other measures, improve journalist safety.

Babar’s family also refused to let matters lie. His brother, Murtaza Khan Babar, hired lawyers to assist the prosecution, but threats drove two of them to drop out. Another was killed. He spent 1.5 million Pakistani rupees (about US$15,000), in a country where the average annual salary is just over $3,000. “My business suffered. I sold my house,” recalled Babar’s brother, who also fears for his own safety as long as some of the suspects roam free.

His petitions and the immense pressure surrounding the tumultuous case led to a relocation of the trial from Karachi to an anti-terrorism court in Shikarpur, where the powerful network backing the accused had less reach and influence. Anti-terrorism courts expedite proceedings and offer a more protected environment. Though too late to have a direct bearing on the Babar case, the Sindh provincial assembly passed legislation to establish a formal witness protection program in late 2013. The verdict that followed has laid the groundwork for Pakistan to reverse its record of impunity. “Now anyone who murders journalists will think 10 times,” said Murtaza Khan Babar.

The elements behind this conviction showcase strategies that can be effective in fighting impunity. Trial relocation to ensure a fair process and greater protection of witnesses have been used to secure convictions in other cases. In the Philippines, the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, with the help of private prosecutors, successfully petitioned for venue changes in the trial of those accused of killing Marlene Garcia-Esperat and other cases that ended with convictions of key suspects. Intense media coverage by Brazil’s TV-Globo after drug traffickers abducted and murdered its reporter Tim Lopes in 2002 pushed the authorities to get complete justice; it also galvanized Brazil’s media to begin a fight against impunity that continues today. The sacrifices and determination of family members, like Murtaza Khan Babar and Myroslava Gongadze, are indispensible. Foremost, support at the highest levels of leadership is what makes or breaks justice.

A CPJ delegation visited Pakistan in March 2014 shortly after the verdict and raised the Babar case in meetings with Prime Minister Sharif and other government officials. They widely agreed that the proceedings offered lessons to be learned and an opportunity for Pakistan to go from reprobate to model on this issue. Sharif made several commitments during the meeting that, if implemented, could sustain momentum. They include establishment of a joint government-journalist commission to address continued attacks on journalists and impunity; changing trial venues in other cases; and expanding witness protection programs. Pakistan Information Minister Pervaiz Rasheed said the government would appoint both provincial and federal special prosecutors to investigate crimes against journalists.

It would be grossly incorrect to say a new page has turned for impunity in Pakistan. The government has not yet made good on these pledges. Justice has not been meted out for witnesses and prosecutors who were killed in the course of the Babar trial, and it remains stalled in other journalist killings. In many ways the situation has worsened in Pakistan since the verdict and CPJ’s visit. There have been several new attacks, including the shooting of Geo News’ senior anchor Hamid Mir. And the government has harassed the Jang Group’s media outlets after its assertions that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence perpetrated the attack on Mir. But Babar’s case offers a glimpse, however brief, of a future where justice is possible even in the most hostile media environments.