4. Steps That Work and Those That Don’t

On May 3, 2011, CPJ representatives traveled to Pakistan to raise concerns about the increasing attacks against journalists there and the country’s high rate of impunity. It was a moment of drama: The previous day, American forces had killed Osama bin Laden in nearby Abbottabad. But Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari kept his commitment and met CPJ to discuss the growing number of Pakistani journalists murdered because of their work, and the absence of prosecution against the assailants.

Zardari made strong commitments at the meeting. “The protection of journalists is in my mandate,” he told the delegation. Zardari asked the interior minister to provide detailed information on the status of the outstanding cases and ordered his cabinet members to work with Parliament to develop new legislation strengthening press freedom.

The Road to Justice

• Table of Contents

• Sidebar: Serbia murders

Multimedia

• Slideshow

In print

• Download a pdf

In other languages

• Español

• Français

• Português

• العربية

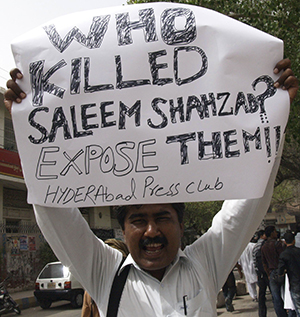

• Русский

Since then, 11 more journalists have been murdered in Pakistan. Just weeks after the meeting, the body of investigative journalist Saleem Shahzad was found with signs of torture—a victim, past threats against him suggested, of Pakistan’s Inter-Intelligence Services directorate. Neither Zardari nor his cabinet members produced the promised follow-up information, nor did his government pass legislation that might bring relief from the constant barrage of threats faced by journalists in Pakistan.

CPJ returned to Pakistan nearly three years later and this time met with Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. Sharif readily acknowledged that Pakistan had a problem when it comes to preventing or punishing violent attacks against journalists. He agreed to take up several of CPJ’s proposals to address impunity, including the establishment of a special prosecutor. He even threw in his own idea of creating a joint commission involving government, civil society, and media to review unsolved cases and other press freedom threats. These commitments have not moved substantially forward.

CPJ’s meetings with the top leaders in Pakistan and other countries with poor records of solving journalist killings reflect a familiar pattern: Commitments from these governments go largely unfulfilled. Years of intensive advocacy by press freedom groups, human rights organizations, and journalists around the world have transformed the issue of deadly anti-press violence into one that governments now readily admit. Many, like Pakistan’s leadership, pledge to address it. What’s often lacking is the next step: action.

CPJ has elicited similar pledges elsewhere. In 2008, President Masoud Barzani, head of the Kurdistan Regional Government, promised CPJ’s visiting delegation that it would “create an atmosphere that is conducive to journalism.” By 2014, when a CPJ team revisited Kurdistan, a range of new attacks had taken place, including the murders of two journalists and an arson attack on a TV station, all unpunished. “The government, from the president to the prime minister and across its branches, takes those cases seriously and will do everything it can to ensure justice,” Interior Minister Karim Sinjari told CPJ’s second delegation.

Other groups have experienced similar disappointments. In Iraq, the government made a pledge to the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) to establish special chambers in consultation with the journalist’s union to investigate the killings of journalists. “This has yet to happen,” Ernest Sagaga, IFJ’s head of human rights and safety, told CPJ.

In the Philippines, press freedom activists have been disappointed that despite repeated commitments to act strongly against impunity and violence against the media, President Benigno Aquino III has brought little change. At least eight journalists have been killed for work-related reasons in the Philippines since his election in 2010. “We weren’t expecting any miracles” from Aquino “that suddenly everything would be happy and just, but we were expecting that he would at least initiate the reforms necessary to lead the way to justice,” said Rowena Paraan, chair of the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines. “But he hasn’t done that.”

It was not always the case that officials were even ready to meet and discuss ways to address impunity in their countries.

In Russia, for example, it took three CPJ missions to get the authorities to sit down and discuss the high number of unprosecuted murders there. Promises made to a delegation in 2009 to demonstrate progress in each case submitted by CPJ have fallen short. But noteworthy movement has occurred in several cases, including convictions in three, though in none have the crimes’ perpetrators been sentenced.

The Inter-American Press Association paved the way for freedom of expression groups when it began its regional impunity campaign nearly two decades ago. The campaign’s director, Ricardo Trotti, recalled the early challenges in making impunity in journalists’ attacks a cause for widespread concern. “At the beginning of our campaign in 1995, the issue of impunity was not one of public debate and the authorities were not reacting,” he said. Years of “constant preaching,” in the form of reports, missions, public awareness campaigns and the use of the Inter-American Human Rights System helped put the issue on the public agenda, he said. “Thanks to that, governments felt more under pressure to respond.”

“There began to be more laws on the protection of journalists, special prosecutor’s offices were set up, the issue was made a federal matter in Mexico, punishment was increased in penal codes, and some offenses were declared as crimes against humanity,” Trotti said. “Clearly, we did not reach perfection, or even much less, but very useful legal and judicial mechanisms were achieved.”

In some countries, the battle to get governments to give recognition and attention to anti-press violence and impunity has been more frustrating. Edetaen Ojo, executive director of the Nigerian press freedom group Media Rights Agenda, observed that there is little public reference to the issue by high levels of government, let alone attempts to address it. “No policy, legislative or administrative measures have been put in place during this period to address the situation,” Ojo said.

“Zero impunity” is the declared goal of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. In May 2014, a CPJ-led international delegation met with Rousseff and Brazil’s ministers for justice, human rights and social communications in Brasília. They presented findings and recommendations from “Halftime for the Brazilian press: Will justice prevail over censorship and violence?” a CPJ special report. In the meeting, Rousseff said, “The federal government is fully committed to continue fighting against impunity in cases of killed journalists.”

Brazil’s fight may be a long one. Despite its standing as one of the world’s largest economies, with a diverse and vibrant press, the host of the recent World Cup still ranks as the 11th deadliest country in the world for journalists. At least 27 journalists have been murdered in Brazil in direct reprisal for their work since CPJ began tracking killings in 1992. Ten of these murders took place since Rousseff came to power at the start of 2011, CPJ research shows.

Though Brazil has made impressive strides recently in achieving convictions, the country ranked 11th on CPJ’s 2014 Global Impunity Index, with nine unsolved murders for the 2004-13 period covered by the survey. Government officials are the leading suspects in the majority of cases. The problem of violence and impunity is more extreme for provincial journalists than for their colleagues working in urban areas. Killers often target journalists who cover corruption, crime, or politics—like Rodrigo Neto, shot in March 2013. Investigations frequently identify the assailants, but they are prosecuted only intermittently.

In “Halftime for the Brazilian Press,” CPJ reported that justice for many Brazilian journalists targeted for their work has been “halting and incomplete.” The report cited several cases in which strong investigations led to arrests. But family members and colleagues of the victims, the report said, find that “the chains of accountability broke down once the case reached the judicial branch,” often due to corruption.

In one murder case, Edinaldo Filgueira, founder and director of the local newspaper Jornal o Serrano in northeastern Serra do Mel, frequently denounced city government on his blog. He was shot six times by three unidentified men outside his office on June 15, 2011. A special investigator was assigned to the case and the initial results were encouraging. In December 2013, seven men were convicted of planning and participating in the crime, including the gunman. Another man, Josivan Bibiano, mayor of Serro do Mel at the time of Filgueira’s death, was charged with being the crime’s mastermind. He was jailed twice but later released in a decision viewed by critics as irregular. There is no indication of whether he will be tried.

International and domestic freedom of expression groups like the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists, or ABRAJI, have lambasted Brazil’s record of incomplete justice and failure to protect journalists, and have campaigned for a strong response from the government. Other colleagues have formed grassroots movements around the cases of Neto and Filgueira. In Filgueira’s case, a local community of bloggers established a National Bloggers’ Day in his honor to keep the case in the public eye. The press corps in Neto’s home state, Minas Gerais, founded the Rodrigo Neto Committee after the murders of Neto and Walgney Assis Carvalho, a photographer from the same newspaper, Vale do Aço. The committee pressed the authorities for a full prosecution in the cases.

The pressure has yielded results.

In late 2012, the administration of Rousseff, who sought re-election this year, formed a working group to investigate attacks on the press and prepare recommendations to the federal government. The group included several civil society organizations, presidential advisers, and the communications and justice ministries. Its report, issued in March 2014, documented 321 cases of murder, kidnapping, assault, death threats, arbitrary detention, and harassment from 2009 to 2014. It also gave extensive recommendations to the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the federal government, some addressing impunity as well as protection.

The group advised that the Human Rights Ministry and the Ministry of Justice establish a national Observatory on Violence Against Journalists in cooperation with local field offices of UNESCO and the United Nations Information Center to chronicle press violations and create a system of investigations and resolution. It also urged Congress to provide for federal police involvement in investigations of crimes against freedom of expression—particularly in cases when there is evidence of omission, lapses, or complicity by local authorities. In addition to the working group’s proposal, a bill under consideration by Congress aims to speed cases through the judiciary.

Most significantly, Brazil has increased its convictions. In 2013, Brazil’s courts sentenced perpetrators in three cases of journalist murders, more than any other country in a single year over the last decade. In addition to the partial justice meted out last year in the case of Filgueira, a 27-year prison sentence was handed to the killer of crime reporter Francisco Gomes de Medeiros, shot five times in front of his home in 2010. The mastermind behind the 2002 murder of newspaper owner, publisher, and columnist Domingos Sávio Brandão Lima Júnior was also convicted in 2013. In 2014, two men were sentenced for the 2012 murder of journalist and blogger Décio Sá.

In May’s meeting with CPJ, President Rousseff pledged to address impunity during the United Nations General Assembly in September. If Brazil can comprehensively implement the recommendations of the working group, and continue to secure convictions, it will show that state commitments are not always hollow, setting a model for other countries to fulfill theirs.

Brazil is not the only country to consider federal action to bring justice to media killings. From Mexico to Somalia, states have responded to pressure to rein in impunity through actions such as legislation, creation of task forces, and appointments of special prosecutors and commissions. These have met with varying degrees of success. Some initiatives opened new doors on old cases; some were well conceived but poorly resourced; some were little more than a means to deflect criticism.

In few places would an effective mechanism be more welcome than in Somalia, the second-worst country in the world after Iraq when it comes to solving journalist killings. In 2012, the announcement by Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud of a new task force to investigate all cases involving the killing of journalists offered some hope during a bleak year during which 12 journalists were murdered. This kind of push from the government to mobilize Somalia’s police is badly needed, Somali independent journalist Abukar Albadri said. “The police don’t normally visit the crime scene to start an investigation,” he said. “They are not interested in investigating a journalist’s murder.”

Two years later, however, there is little to show. In only one of 27 cases of journalists assassinated in Somalia since 2005 were any perpetrators convicted. Authorities executed a suspect in the 2012 murder of Hassan Yusuf Absuge, though lack of due process in the case led many to view the development with concern.

According to one government representative, the task force was formed but lacks money to operate. “The task force was set up last year and they really conducted investigations on cases; however, due to no budget and funding, it was difficult to carry out their work efficiently,” said Abdirahman Omar Osman, senior media and strategic communications adviser to the Somali government. “They still exist but cannot function without resources.”

Osman noted the lack of international help, despite pledges from the United Kingdom and elsewhere to increase aid for institution-building in Somalia. “There is no funding at all on this regard from international partners,” he said, “and no expertise in this field.”

Albadri, though, said the government could demonstrate more political will and accountability. “We never had a report from the government where either the police or the ministry for information explained any detail related to investigations,” he said. “Promises don’t work if the government doesn’t order the police to take the matter seriously and investigate the cases and bring the alleged culprits to justice.”

In the Philippines, meanwhile, the government in recent years established an array of task forces under the Philippine National Police, but they were criticized as “useless” by the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines. Advocates there suggest a better approach would be rapid response teams that include civil society and government representation and that could be dispatched immediately after an attack.

Establishing an investigative body dedicated to specific cases can bring results, but not when its findings are paltry or opaque. After the Pakistani media widely protested the murder of Saleem Shahzad, the government opened a commission of inquiry. Shahzad, who had written about alleged links between Al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Navy before his disappearance in May 2011, had received threats from Pakistan’s Inter-Intelligence Services. The commission’s report, issued in 2012, included strong recommendations for instilling greater accountability in the conduct of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, but it failed to identify any perpetrators.

Though disappointingly inconclusive, the Shahzad commission made it one step further than the judicial inquiry formed in response to the 2006 abduction and murder of Pakistani journalist Hayatullah Khan. Despite repeated calls from domestic and international press freedom groups, that report has never been made public.

In another case of a commission yielding no results, President Masoud Barzani of Iraqi Kurdistan announced the appointment of a committee to investigate the murder of a popular student journalist, Sardasht Osman, abducted and killed in 2010. No details of the committee’s makeup or its findings have since been released. CPJ urged full disclosure of the committee’s activities in a special report on impunity in Kurdistan and in meetings with government officials this year.

Colombia established a special sub-unit under the Public Prosecutor’s Office to conduct investigations into crimes committed against journalists, but this has not led to more effective or efficient prosecutions, CPJ has found. However, the controversial 2005 Law of Justice and Peace, which grants leniency to members of illegal armed groups in exchange for demobilization and full confessions to their crimes, has helped establish the truth in some older cases, and led to a conviction in the 2003 murder of radio commentator José Emeterio Rivas.

In situations where impunity is fed by corruption, collusion, or lack of resources by local and provincial authorities, many look to models that allow national agencies to investigate when a journalist is a victim of violence. This has been encouraged in Brazil and in Mexico. In the latter, lawmakers approved legislation in April 2013 supporting enactment of a constitutional amendment that gives federal authorities jurisdiction to prosecute crimes against journalists. Though the law is viewed as an important step toward improving press freedom in Mexico, seventh on CPJ’s 2014 Impunity Index, little has come of it so far.

Under the new power, Mexico’s Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes Committed Against Freedom of Expression, known as the fiscalía, can claim control of investigating crimes committed for reasons having to do with practicing journalism. But journalists told CPJ that the office is slow to exercise this power.

They point to the case of Gregorio Jiménez de la Cruz, who was kidnapped on February 5, 2014, from his home in Veracruz. Jiménez had reported on sensitive topics such as abuses against migrant laborers, but the federal prosecutor’s office has not intervened because it says it has not determined that journalism was a motive. Press freedom advocates say this is a step that should come later, when an effective investigation has taken place. “If you take the option of investigating to see if it is related to journalism, you’re going to lose time,” said Javier Garza Ramos, a journalist from Mexico who also specializes in security training and protection for the media.

Special Prosecutor Laura Borbolla told CPJ in an interview that it has been difficult to get information from authorities in Veracruz. “What I believe is that they are guarding their political image,” she said. “This undoubtedly harms an investigation or coordination.”

There is much riding on Mexico’s ability to make this program successful, not only for its own journalists but also for media communities in other countries, desperate for evidence that it’s possible to break cycles of violence and impunity. One local official working with an international organization observed, “If the fiscalía starts winning sentences, it will send the message that the trend is being reversed or can be reversed. This is something any state or any government will read and understand.”