Nigeria’s press freedom record is on the decline.

For the first time since 2008, when CPJ began publishing its annual Impunity Index, Nigeria has made the list of the “worst nations in the world for deadly, unpunished violence against the press.”

Dapo Olorunyomi, leading Nigerian journalist and editor-in-chief of online newspaper Premium Times, in an op-ed encapsulated the state of Nigeria’s press as “perhaps the most dismal” since the country’s return to civil rule in 1999. Citing Islamist terrorists in the North and national insurgents in the South; thieving politicians; a swelling climate of intolerance; criminal gangs sustained through official corruption, oil theft, and kidnappings; ethno-national mobs; and politically-financed terror squads, Olorunyomi says this recent wave of impunity has “finally come home to roost.”

“These are the notations of impunity, the hydra-headed monster that now threatens freedom, rights, and ultimately, the democratic aspirations of citizens. In all climes, reporting events like these comes at dreadful costs,” Olorunyomi wrote.

The Nigerian government has tried to downplay these facts. Presidential spokesman Reuben Abati told daily Leadership that CPJ’s report is “referring to journalists caught in the cross fire of the Boko Haram activities in the North and it is in protest to the security challenges in the Northern part of the country.” He said CPJ’s survey “promotes sensationalism, rather than the truth” and is “not a true reflection of journalists in the country.”

Abati got it wrong on several fronts.

Firstly, CPJ’s Impunity Index, published since 2008, does not include cases of journalists killed in combat. It documents countries where journalists are deliberately killed in relation to their work and their killers go unpunished. It is published to commemorate World Press Freedom Day marked yearly on May 3.

Indeed, the murders of five journalists in Nigeria during the decade covered by this year’s Impunity Index–January 1, 2003, to December 31, 2012 –remain unsolved. These are Channels TV reporter Enenche Akogwu in 2012; Zakariya Isa of the state-broadcaster NTA in 2011; Nathan Dabak and Sunday Gyang Bwede of the Light Bearer monthly newspaper in 2010; and Bayo Ohu of The Guardian in 2009. Nigeria is second only to Somalia in terms of Africa’s worst record on unpunished journalist murders.

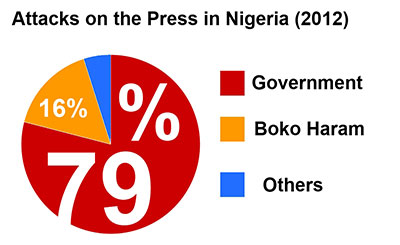

Secondly, Abati’s assertion that anti-press violence in the country is not about the relationship between media and the authorities is wrong. In 2012, CPJ documented 143 attacks on the press in Nigeria. Government and security forces were responsible for 79% of the cases, while Boko Haram militants were behind only 16%.

Thirdly, Abati claimed that journalists practice their profession “with the utmost freedom” and with “no media repression in Nigeria.” CPJ counters these claims with an invitation to Abati to visit CPJ’s page on Nigeria where–among other things– exactly a year ago today on World Press Freedom Day, I reported how police authorities locked up seven journalists at the Special Fraud Unit in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, to prevent them interviewing the former state governor and current parliamentarian, Bukola Saraki, whom police had summoned to respond to allegations of involvement in a multimillion dollar fraud.

Chuks Ehirim, the Abuja chapter chairman of the Nigeria Union of Journalists, also weighed in on the sorry state of Nigeria’s press corps, contradicting Abati. Ehirim said Nigerian journalists face recurring arrests, beatings, and detentions without trial, either at the hands of government security agents or highly placed individuals, Leadership reported.

“Journalists are still being killed unnecessarily in Nigeria… Although we are happy that, today, the world will be celebrating Press Freedom Day, but I think that Nigeria will be aside, because there is nothing to celebrate here,” Ehirim said.