2025 journalist jailings remain stubbornly high; harsh prison conditions pervasive

- English

In This Report

Introduction

For the fifth year in a row, more than 300 journalists were imprisoned worldwide as of the end of 2025, according to CPJ’s annual prison census. These record-setting numbers reflect growing authoritarianism and escalating numbers of armed conflicts worldwide. Often, journalists are held under cruel and life-threatening conditions – “a cemetery of the living,” as one freed Palestinian prisoner described it.

Many imprisoned journalists bear these dangers for a long time, according to the census, an annual snapshot of journalists imprisoned as of 12:01 a.m. on December 1. More than one-third of the 330 in the 2025 census are serving terms of more than five years. Nearly half have never been sentenced at all, and of those, 26% have languished in jail without sentences for five years or more. Such detentions are in violation of international law, which requires fair trials without undue delay.

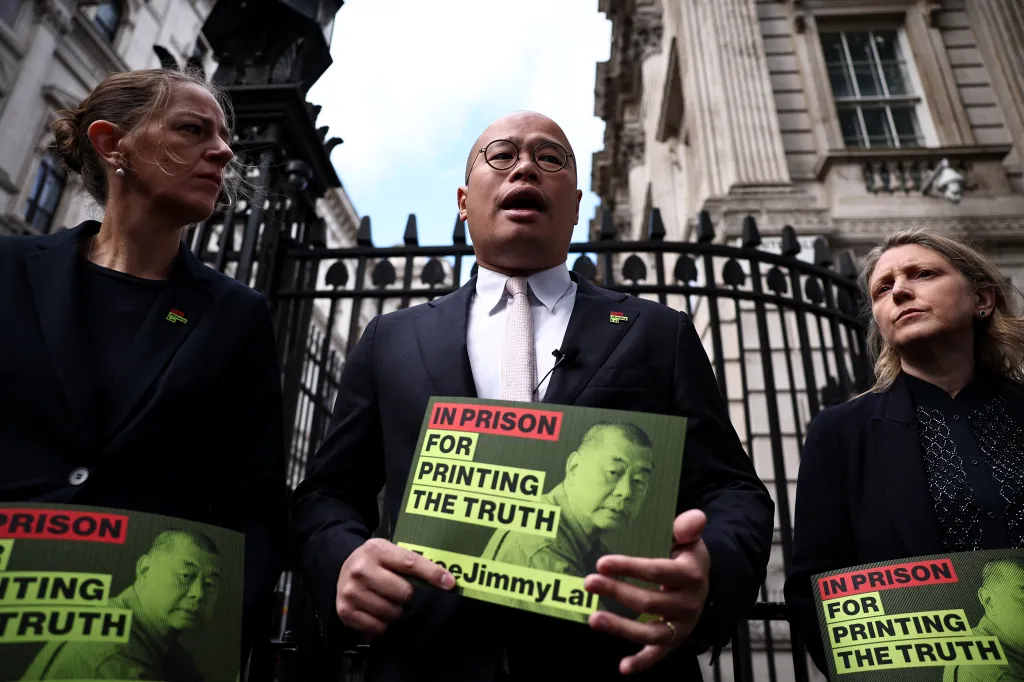

To stem the tide of imprisonments, CPJ has continuously called on governments to uphold the rule of law and to stop criminalizing those who report factually and hold power to account. CPJ mobilizes political pressure and international expert interventions, spearheads solidarity campaigns, and takes legal action. Together with partners, CPJ seeks to halt or reform legislation that can hinder reporting and put journalists in legal jeopardy.

CPJ also directly supports a rising number of imprisoned and newly released journalists with legal, medical, trauma, and other health-related assistance. Over the past five years, the number of journalists who received both prison and post-prison support from CPJ rose by almost 200%.

While 2025 has seen a slight reduction in jailed journalists, down from a record 384 in 2024, the numbers remain stubbornly high. It has been more than a decade since fewer than 200 journalists were jailed.

Global deterioration of democracy and erosion of human rights protections have paved the way for both new and old authoritarian leaders to suppress press freedom in recent years. Russia’s longtime tactic of jailing and fining independent journalists who accept foreign funds has spread to nations like Azerbaijan, Hungary, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, while countries like India and Tunisia have created new legal pretexts to jail journalists on claims of tax, defamation, or security violations.

In many countries, there is little to no recourse for a wrongfully jailed journalist. Although some groups are working to create an international mechanism for exoneration, the lack of accountability makes it easier for authorities to jail journalists under shaky pretexts – and to mistreat them while they are imprisoned.

China’s status as the world’s worst jailer of journalists, with 50 held in 2025, has now extended to three years consecutively. Myanmar, with 30 held, rose to the second worst from third in 2024, and Israel, with 29 imprisoned, dropped to the third worst jailer from the second in 2024. Azerbaijan, which imprisoned 24, joined the top ten for the first time since 2018, nearly doubling its number of prisoners from the prior year in a months-long crackdown on the independent press. Numbers imprisoned in Russia, Myanmar, Belarus, Egypt, and Eritrea were similar to those in the past five years.

Israel, the only country on the worst jailers’ list that is traditionally considered a democracy, began imprisoning Palestinian journalists rapidly following the start of the Israel-Gaza war in October 2023. Often, journalists are imprisoned on undisclosed charges or held without charge in arbitrary detention – in contravention of international law. While Israeli citizens enjoy some civil rights and freedoms, legal experts identify a radically different standard of justice for Palestinians in its occupied territory. Israel arrested more than 90 journalists during the course of the war.

Israel is not the only country claiming to be free or partly free but still detaining journalists: Georgia, Guatemala, and the semi-autonomous region of Hong Kong also share this dubious distinction. The United States, joined the list of jailers of journalists in 2025, with its months-long detention of journalist Mario Guevara, although Guevara was deported before the December 1 census was taken.

The majority of journalists — 61% of those jailed worldwide — continue to be jailed for “anti-state” charges, which include accusations of terrorism or accepting funds from a foreign government. Politics remains the beat most likely to result in a journalist’s imprisonment ー more so than human rights, corruption, or war.

“Persecuting journalists is a means of silencing them. That has profound implications for us as individuals and for society as a whole. Corruption goes unchecked, abuse of power is allowed to flourish, and we are all at greater risk as a result.”

— CPJ CEO Jodie Ginsberg

Many of the world’s worst jailers of journalists, such as Turkey, China, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Myanmar, are nations that consistently view political opposition — and coverage of that opposition — as a threat to be silenced. Journalists in these countries have been jailed on accusations including terrorism, espionage, and cooperating with exiled media. Election protests and coverage of opposition parties have also triggered arrests in repressive countries.

These imprisonments of reporters are not just a symptom of authoritarianism; they are an accelerant. Studies have shown a clear link between attacks on the media and declines in democracy.

“Persecuting journalists is a means of silencing them. That has profound implications for us as individuals and for society as a whole,” said CPJ CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “Corruption goes unchecked, abuse of power is allowed to flourish, and we are all at greater risk as a result.”

In addition to the annual snapshot of jailed journalists, CPJ’s database on imprisoned journalists now includes current data on imprisoned journalists, which can be tracked throughout the year.

The horror behind bars

Since CPJ began keeping records in 1992, it has documented hundreds of cases in which journalists, their lawyers, or their families have reported mistreatment in prison. There are likely hundreds more that will never be documented because captors often suppress information, or journalists and their loved ones are afraid to reveal it due to fear of retaliation. In 2025, nearly one-third of imprisoned journalists’ profiles included reports of mistreatment, including 20% with claims of torture or beatings. The greatest number of torture and beating claims since 1992 have occurred in Iran, followed by Israel and Egypt.

Severe mistreatment such as this sometimes can result in death.

Freed journalists and others who feel safe enough to come forward have described horrific ordeals, including permanent injuries from torture and beatings, mock executions, sexual and psychological abuse, and denial of food and medical care.

Finally freed: In the 2025 census year, 116 journalists were released from prison, including CPJ 2025 International Press Freedom Award winner Sonia Dahmani; Iryna Slaunikava and 7 other Belarusian journalists; and Egyptian blogger Alaa Abdelfattah.

CPJ assisted 36 journalists with prison support in 2025, mostly in Azerbaijan and Russia. This number represents a more than five-fold increase from the seven imprisoned journalists CPJ supported in 2021. The increase is due to more support requests from journalists incarcerated in these countries, but also reflects increased response capacities from CPJ, including via local contacts and partners able to reach hard-to-access journalists in jail. Incarcerated journalists often lack basic necessities, including food, water, and hygiene products. An assistance grant from CPJ can cover these costs, as well as pay prison visits from family members or legal representatives.

Strikingly, CPJ also provided 29 journalists with post-prison support — double the previous year — to help them re-establish their livelihoods following incarceration. Support after prison is often holistic; in many cases, CPJ has supported journalists who also need medical, trauma, and legal support upon their release, illustrating the complex nature of recovery.

5 journalists recall their ordeals behind bars

Silence is not an option

5 journalists still imprisoned, and how CPJ is fighting for them

China

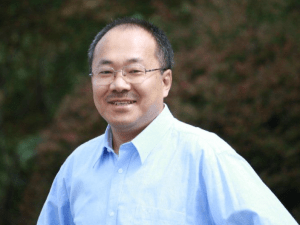

Dong Yuyu: A 2025 International Press Freedom Award winner and veteran editor and columnist, Dong was arrested in February 2022 while having lunch with a Japanese diplomat in Beijing. He was convicted of espionage in November 2024 and sentenced to seven years in prison. Dong’s imprisonment underscores the growing trend of using espionage and security charges to target journalists in China, which held at least 50 journalists behind bars as of December 1.

What he is enduring: China’s overall prison conditions have been described as harsh and life-threatening. For nearly four years, Dong’s family had been unable to see him after he was detained, and his only contact with the outside world was through lawyers who visit monthly. His family was only able to visit Dong for the first time in December 2025. His family has also raised concerns about his health and nutrition, given his age of 63. Dong’s appeal, submitted a month after his conviction, was postponed three times before a November 2025 hearing, at which his harsh seven-year prison sentence was upheld.

The fight to free him: CPJ advocates, alongside Dong’s family, for his immediate release. CPJ has written to Chinese authorities repeatedly, including separate letters to the Chinese President Xi Jinping and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, urging them to free Dong. CPJ has also advocated for Dong with the U.S. Congress and the U.S. State Department. Following this, U.S. Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi referenced Dong’s case in a November report on the Chinese Communist Party’s escalating assault on democracy and human rights. The Congressional-Executive Commission on China’s 2025 annual report also highlighted Dong’s imprisonment, while members of Congress condemned the Chinese court’s decision to uphold Dong’s seven-year prison sentence, and the State Department agreed to focus attention on his case. In December 2025, the European Union Delegation to China called for Dong’s unconditional release.

China was the world’s worst jailer of journalists in 2025 and routinely tops CPJ’s prison census

Mistreatment* in China and Asia as a whole:

China

31+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

5+

of those include claims of torture

Asia

94+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

18+

of those include claims of torture

Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory

Farah Abu Ayash: Arrested twice in 2025, Palestinian broadcast reporter Ayash’s latest detention occurred on August 6, when Israeli forces arrested the 24-year-old in the West Bank city of Hebron. Out of 29 Palestinian prisoners jailed by Israel, Ayash is one of 27 held under arbitrary detention, meaning no charges have been formally filed. Her attorney told CPJ that Israeli police accused her of having “contact with a foreign agent,” without elaborating. Her father told CPJ her detention has been extended twice, and the family is unable to communicate with her.

What she is enduring: Ayash told her attorney about a myriad of abuses: Military dogs attacked her as she was arrested, and she was later tied to a leaking water pipe that soaked her throughout the night. She called West Jerusalem’s Al-Moskobiya prison a “horror movie.” Ayash spent 55 days in solitary confinement and suffered from medical neglect, routine beatings, and verbal abuse. She was also jailed in Ayalon prison in the central city of Ramla, where she said she was held in a cell infested with vermin. Other Palestinian prisoners have claimed similar abuses, CPJ data shows.

The fight to free her: CPJ challenged the legality of Israel’s use of administrative detention to hold journalists without charge via the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. In September 2024, the group ruled in favor of CPJ’s submission, finding that Israel’s detention of three Palestinian journalists because of their work, their“peaceful exercise of their right to freedom of opinion and expression,” and their use of administrative detention was discriminatory, arbitrary, and in violation of international law. Despite being given an opportunity, Israel refused to engage with the working group, which has urged Israel to end its use of administrative detention, release detained journalists, and provide appropriate remedies, including compensation for unlawful detention.

Israel has been listed as a top jailer of journalists since 2023

Mistreatment* in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and in the Middle East and North Africa region as a whole:

Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory

38+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

11+

of those include claims of torture**

Middle East and North Africa

224+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

58+

of those include claims of torture

**CPJ is currently investigating reports of torture in Israeli detention centers that could substantially raise these numbers.

Ethiopia

Genet Asmamaw: Caught in a wave of journalist arrests in April 2023, Internet reporter Genet was charged with terrorism and could face the death penalty if convicted. The arrests came as conflict erupted between the Ethiopian government and insurgent security forces in the country’s Amhara region. She was denied bail, transferred to a maximum security facility, and pleaded not guilty in November 2023. Genet’s trial started in February 2025 and was ongoing as of December 1. Four other journalists were imprisoned in Ethiopia as of December 1.

What she is enduring: Five federal police officers beat and intimidated Genet during her arrest at home in April 2023, according to her lawyer, Henok Aklilu, and brother, Andualem Demissie. Genet later told a court about the abuse, and the court ordered the federal police to investigate, Henok said. CPJ was unable to determine whether the investigation was carried out. Prison conditions in Ethiopia are harsh, with torture and mistreatment occurring “in particular for against people suspected of terrorism,” according to one report.

The fight to free her: CPJ closely monitors conditions for Genet and other detained Ethiopian journalists, providing frequent and public accounting of their trial and prison conditions. In April 2024, CPJ submitted Genet’s case to the United Nations Human Rights Council as part of Ethiopia’s Universal Periodic Review, urging authorities to end the use of terrorism charges against journalists and to guarantee due process and press freedom. That submission covered the cases of nearly 100 journalists arrested over a five-year period. Her detention has also been cited in the U.S. Department of State’s 2023 and 2024 annual human rights reports on Ethiopia, which referenced CPJ’s reporting on her arrest, alleged abuse, and prosecution.

Ethiopia has jailed journalists almost every year since 1993

Mistreatment* in Ethiopia and Africa as a whole:

Ethiopia

16+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

0+

of those include claims of torture

Africa

64+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

7+

of those include claims of torture

Russia

Anastasiya Glukhovska: Detained on undisclosed charges since August 2023, Glukhovska was working as a reporter in Melitopol, a city in Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia region, before Russia occupied it shortly after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, her sister told CPJ. In October 2023, her detention was made public when Russian media reported the news. Glukhovska’s family has been unable to get any information about why she was detained. Twenty-six other journalists, including 11 Ukrainian journalists, were also held by Russia as of December 1.

What she is enduring: A former cellmate told Ukrainian media outlet Slidstvo.Info that Glukhovska had first been held in Melitopol in a makeshift detention site in the basement of a local company’s building. The cellmate said she had heard Glukhovska screaming and that Glukhovska told her she had been subjected to electric shocks. A recent report about Kizel prison, where Glukhovska is now reportedly being held, and the same facility in which journalist Viktoria Roshchina was murdered, detailed numerous abuses of inmates, including constant beatings.

The fight to free her: CPJ closely monitors detention conditions of Glukhovska through contacts with her family and frequently addresses Russian authorities for comment on the charges against her. CPJ has flagged her case to U.S. government officials. In November 2025, CPJ published a Q&A with Ukrainian journalist Vladyslav Yesypenko, who spent over four years in a Russian prison and has been advocating for the release of Glukhovska and all other 11 Ukrainian journalists currently held by Russia.

Russia has been a top jailer of journalists for the past five years, with numbers escalating amid the war with Ukraine.

Mistreatment* in Russia, and Europe and Central Asia as a whole:

Russia

18+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

5+

of those include claims of torture

Europe and Central Asia

95+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

30+

of those include claims of torture

Guatemala

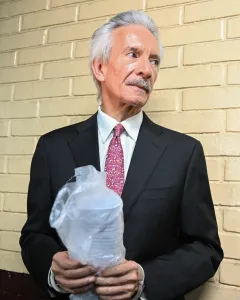

José Rubén Zamora Marroquín: Zamora, a veteran investigative journalist and founder of the now defunct Guatemalan newspaper elPeriódico, was arrested in July 2022 and sentenced in June 2023 on money laundering charges that were widely condemned as retaliation for his journalism. An appeals court overturned his conviction in October 2023. He was released under house arrest on October 18, 2024, after over 800 days of arbitrary detention, but was ordered back to jail on November 15, 2024. He continues to wait for a retrial and hearing dates in pre-trial detention. A CPJ International Press Freedom Award winner, Zamora has now been held for more than three years. He is the only journalist jailed in Guatemala.

What he is enduring: An international legal team appealed to the United Nations in 2024 for Zamora to be freed, as he was being arbitrarily detained and held in conditions “that amount to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment,” including “sadistic humiliation ceremonies,” sleep deprivation, unnecessary restraints, and unsanitary conditions that pose a threat to his health. Before his imprisonment, Zamora was subject to years of lawsuits, intimidation, and threats on his life. While he was imprisoned, elPeriódico was shut down due to government pressure.

The fight to free him: CPJ continues to monitor Zamora’s condition and advocate for his unconditional release. CPJ has repeatedly urged judicial authorities to schedule overdue hearings and guarantee due process. In 2025, CPJ visited Zamora twice in prison and met three times with Guatemala’s president, prompting President Arévalo to publicly cite the case, including at the UN General Assembly, as a clear example of political persecution by a co-opted Attorney General’s Office. These meetings also helped advance efforts to draft comprehensive legislation to protect journalists. In Washington, D.C., CPJ has pushed Zamora’s case before the U.S. Congress, Senate, and Department of State. As a result of this advocacy, Senator Durbin raised the case on the Senate floor and called for Zamora’s release.

The Americas region has consistently jailed the fewest journalists. Cuba has appeared on the census most frequently since 1992.

Mistreatment* in Guatemala and the Americas as a whole:

Guatemala

1+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

1+

of those include claims of torture

Americas

32+

reports of journalist mistreatment in prison since 1992

1+

of those include claims of torture

Global imprisonment snapshots as of December 1

Asia

Asia has more journalists in prison than any other region in the world, with 110 behind bars as of December 1. Entrenched repression and government upheaval keep Asia’s imprisoned numbers consistently high.

Top jailers in the region:

- China held at least 50 journalists in prison as of December 1, including seven in Hong Kong. Data indicates a trend of using anti-state charges to target journalists, with at least 34 behind bars for vague and overly broad crimes such as “subversion of state power” and “inciting subversion.”

- Myanmar held at least 30 imprisoned amid a deteriorating media environment since the February 2021 military coup that suspended democracy.

- Vietnam held at least 16 behind bars and continues to be ranked among the world’s worst jailers of reporters, with an atmosphere of deepening repression, despite a change in leadership in 2024.

- Other countries of note— Bangladesh kept four journalists behind bars, and India has two imprisoned. In the Philippines, Frenchie Mae Cumpio has been held in detention for nearly six years without conviction in a case a United Nations expert called “a travesty of justice.”

Europe and Central Asia

The region has the second-highest number of journalists behind bars — 96 — as of the December 1 census. State oppression of the media in Eastern Europe and Central Asia has kept these numbers high.

Top jailers in the region include:

- Russia, a top jailer of journalists since 2021, imprisoned the most journalists – 27 – two in five of those Ukrainian. Russia became a worst jailer in large part due to its imprisonments of both Ukrainian and Russian journalists for coverage of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which began in 2022.

- With 25 journalists in prison, Belarus has fallen from being the worst jailer in the region to the No. 2 spot, although its crackdown on the press continues, seen as retaliation for coverage of President Aleksandr Lukashenko’s disputed 2020 re-election. Many press members are in exile and still face criminal charges.

- Azerbaijan held 24 journalists, up from 13 in 2024, accelerating efforts to silence independent media with laws restricting foreign donor funding. The authoritarian government’s efforts to crush the free press and stifle opposition began in 2023, after Azerbaijan’s military recapture of the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

- Other countries of note — Tajikistan, an ally of Russia, held nine journalists, making it a new addition to the top 10 worst jailers this year. The country’s numbers rose steadily since 2022, as the country’s president stepped up efforts to obliterate independent media. Turkey, with a decades-long record of jailing journalists, had eight imprisoned, two of whom are among 17 arrested in 2025. In Georgia, the Russia-leaning ruling party has rapidly eroded press freedoms, evidenced by the harsh sentencing of media manager Mzia Amaglobeli.

Middle East and North Africa

The MENA region has the third-highest number of imprisoned journalists, with 76 behind bars as of December 1. Most of the imprisonments stem from the Israel-Gaza war; in most other countries, long-term state repression is the culprit.

Top jailers in the region:

- Israel, which, despite a ceasefire and prisoner exchanges, still held 29 Palestinian journalists behind bars, most of them held in arbitrary detention, without due process or legal basis for their arrests.

- Egypt held 18 journalists, and continues its years-long record as one of the worst jailers of journalists, with continued retaliatory arrests of journalists and their family members.

- With eight journalists jailed, Saudi Arabia’s numbers have declined from a peak of 27 in 2019. However, journalists in the country continue to face serious risks, including executions and censorship actions carried out without due process.

- Other countries of note— Iran, with five journalists held, has also seen a reduction in imprisonments since a 2022 high of 55, although arrests continue, particularly of journalists who focus on economic injustices, and those who are jailed face harsh conditions. In Tunisia, three journalists are held as new laws threaten press freedom, but one bright spot came with the November release of IPFA awardee Sonia Dahmani, who was held for more than a year.

Africa

The region has the fourth-highest number of journalists behind bars — 42 — as of the December 1 census. Entrenched authoritarianism and conflicts in the region have fueled many imprisonments. Military and autocratic leaders use accusations of terrorism as a basis to detain journalists who dare to critique governments or report on opposition figures.

Top jailers in the region:

- Eritrea is a consistent entry on CPJ’s worst-jailers list. This authoritarian state has held all of the 16 journalists imprisoned for at least two decades, their legal status, health, and whereabouts unknown.

- All five of the journalists held in Ethiopia, all in the past two years, face terrorism charges after covering the ongoing conflict in the Amhara region, where the ethnic population has faced mass detentions.

- Niger and Rwanda — With five journalists held in each country, most on anti-state charges, press freedom has been under fire for several years. In Niger, a 2023 coup prompted legal reforms and increasing detentions, including five journalists jailed at the end of 2025, an all-time high for the country on CPJ’s census, which had not featured Niger since 2017. Rwanda’s press freedoms have been restricted for years by its authoritarian president, with a steady number kept behind bars since 2018.

- Other countries of note— In Cameroon, where four journalists are imprisoned, the media has suffered four decades of repression, and a president who has promised reform but has worked to silence reporting on his disputed re-election this year. The government’s promise to decriminalize press offenses in Senegal has yet to be kept, as two are still held, including writer René Capain Bassène, whose life sentence was upheld despite flawed evidence.

Americas

The region has the least number of journalists behind bars – six – as of the December 1 census. Although the number of imprisoned journalists is low, political persecution, often for reporting on corruption and gang violence, still leads to arrests, attacks, censorship, and threats to press members.

Top jailers in the region:

- Venezuela holds three journalists: editor Rory Branker, accused of false news in a government crackdown, has been held incommunicado for most of his time in prison since being arrested in February 2025; and reporter Nakary Mena Ramos and camera operator Giani González both imprisoned on April 8, 2025, on charges of “inciting hatred” and “publishing false news” after reporting on rising crime, continues to criminalize independent journalism amid a broader post-election crackdown. Both Ramos and González still do not have trial dates.

- Guatemala, with one journalist arbitrarily detained for more than three years and the continued use of criminal law to harass reporters and threaten them with imprisonment or exile, including those in community media.

- Nicaragua, where journalist Elsbeth D’Anda was forcibly taken from his home and disappeared after reporting on rising living costs, continues to suppress independent media through warrantless raids, opaque detentions, and the systematic dismantling of outlets, driving many journalists into exile under President Daniel Ortega’s continued crackdown against the press.

- Other countries of note— Cuba, where one journalist, Yeris Curbelo Aguilera, remains jailed, and others have either faced threats or fled. And the United States, which held no journalists in prison in relation to their work, has sharply increased retaliation against journalists and news organizations. It has imprisoned, arrested, and refused entry to journalists and writers in 2025 based on their coverage or views.

Download the full dataset spreadsheet used in this report here.

Census methodology

CPJ’s annual prison census is a snapshot of journalists jailed globally for their work as of 12.01 a.m. on December 1. The census includes only those journalists CPJ has confirmed to have been imprisoned in relation to their reporting or coverage by their outlet; it does not include those classified as “missing” or “abducted” if they have disappeared or are held captive by non-state actors.

CPJ defines journalists as people who regularly cover news or comment on public affairs through any medium to report or share fact-based information with an audience.

The census does not include the many journalists imprisoned and released throughout the year; accounts of those cases can be found at http://cpj.org. Journalists remain on CPJ’s list until the organization determines with reasonable certainty that they have been released or have died in custody.

Footnote

* CPJ analyzed hundreds of cases of jailed journalists since 1992 to find those who reported mistreatment while in custody. CPJ categorizes “mistreatment” as reports of: torture, beatings, or injuries by authorities; forced confessions; denials of food, medical care, or access to lawyers and family; sexual assaults; threats of sexual assault or death; and religious discrimination.

Correction: A journalist listed in our database as imprisoned by Ukraine is actually held by Russia, moving Russia’s total imprisoned in the 2025 census up from 27 to 28.

Editor’s note: This report was updated on January 27, 2025, to clarify information on laws in Azerbaijan restricting foreign donor funding.

(Featured image: Reuters/Cristina Chiquin)