Threats to journalists’ safety demand fresh approach

Reporting on wars and natural disasters is inherently dangerous, but the spread of insurgent and criminal groups globally poses an unprecedented risk to journalists. Since the videotaped killings of James Foley and Steven Sotloff in 2014, public awareness of the risks has increased exponentially, but the dangers persist.

The risks include kidnapping for ransom or political gain, and murder by insurgents who see journalists as surrogates of an enemy too powerful to attack directly. Journalists are caught in crossfire or targeted by drug cartels as a warning to other unwelcome reporters. While technological changes enable more people to engage in acts of journalism, those same changes bring new risks, such as surveillance and tracking.

In response, big news outlets and some international correspondents have taken steps to increase safety, but freelancers and local journalists often do not have the resources, including safety equipment and training in physical and digital security, to do so.

Individuals and small outlets lack funds for insurance and security practices, and some journalists accuse news outlets and colleagues of engaging in reckless behavior that puts their selves and others at risk. Post-traumatic stress disorder goes unrecognized or untreated. Multilateral institutions like the United Nations and a handful of individual countries have taken steps to recognize and deal with violence against journalists, but the efforts are uneven and only rarely effective.

And even as new threats to the media emerge, the longstanding threat of government repression persists. Authorities abuse their own laws to censor and imprison those who criticize or seek to investigate wrongdoing.

Repression and impunity endanger the lives and liberty of reporters and foster a climate of fear and self-censorship among journalists and opinion leaders, suppressing news of public interest. This has consequences for all freedoms far beyond freedom of expression. A healthy democracy depends on the free flow of news and opinion to and from the governed. Journalists play a vital role in ensuring that flow and in holding the powerful to account.

Against this backdrop of brutality and intimidation, traditional methods of advocacy are not enough. Journalists must strive to educate themselves about the threats and work in solidarity to combat violence and impunity. Press freedom groups who have relied on direct financial help to at-risk journalists and advocacy with governments must adopt a more holistic approach incorporating physical, digital, and psychological aid.

Shifting threats

The collapse of old political structures, the rise of militias, the failure of Western governments to rein in repressive regimes, and the disruption of the news industry by technology have churned up the threat landscape for journalists globally since the 1990s.

Reporters, particularly domestic reporters working in their own country, have always been vulnerable, but the information is often anecdotal because there was no systematic tracking of strictly journalism-related killings and kidnappings before CPJ began compiling statistics in 1992. Most Western journalists in the post-colonial wars of Asia and Africa did not fear being deliberately targeted because of their work. Kidnappings surged in Lebanon after the U.S. intervention in 1983, epitomized by the high-profile abduction of The Associated Press Beirut bureau chief Terry Anderson, but those were exceptions and the Western hostages were eventually released—although in Anderson’s case, after almost seven years.

“Through the beginning of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, which is where my generation of photographers and journalists came from, the first couple of wars it was very advantageous to mark yourself up with ‘TV,’ ‘Press,’ and so on,” recalled seasoned conflict photojournalist Ron Haviv, who covered the Balkan wars and co-founded the VII Photo Agency. “Literally, there would be times when I would drive up to a front line on one side, ask them to stop shooting so I could drive down the street to go to the other side.”

Media safety specialists, including Tug Wilson from The New York Times, point to the early 2000s as the moment when journalists working in hostile environments began to be perceived as targets. Most notable was the 2002 kidnapping and videotaped beheading of Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl in Karachi. His death signaled a new era in which violent non-state actors use journalists as pawns in asymmetrical warfare with foreign powers.

“What has happened since that time is that because many nations are operating, both covertly and rather publicly, in conflicts around the world, it is very difficult for some of these non-state combatants to attack those governments directly, and so they tend to use journalists as surrogates,” said Robert Picard, North American representative of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, who is also the co-author of a study on the hostage-taking of journalists. “And the idea is to bring pressure on the governments, to bring embarrassment on the governments and to try to extract some policy change from the governments.”

The U.S. invasion of Iraq made clear that “the days of a journalist wandering between opposing sides in a frontline battle space is long gone,” said Wilson.

Fourteen years later, there are some 40 active conflicts around the world and 65 million people have been forced from their homes, the first time forced displacements have topped 50 million since World War II, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. That’s a lot of stories in a lot of dangerous places.

And there are more reporters to get into danger. Demand for freelance work globally has grown because legacy media companies have shrunk expensive foreign bureau networks and new digital media outlets are voracious consumers of content. Thanks to mobile digital technology and a plethora of free publishing platforms, being a foreign correspondent or one-person global news organization has never been easier.

“You have a whole raft of people that are either new to journalism or new to covering foreign conflicts, who are going out either because of necessity or because they think it will be interesting or because they think it will help get them a better position later on, who are willing to take degrees of risk that are much higher, often without full knowledge of what the risks are, and that is a huge problem,” said Picard.

There are no figures for international reporters deployed in any conflict zone at any given time, but anecdotal evidence suggests that demand for news and ease of communication have driven the numbers up while pay rates for most freelancers have stagnated or fallen. Both phenomena have serious consequences for safety.

“I think the main difference that the murders in Syria in the summer of 2014 had was that they raised the profile of the dangers that freelancers are facing,” said independent journalist Emma Beals, a founder and former board member of the Frontline Freelance Register (FFR), a London-based group representing international independent journalists. “You had mums and dads watching ABC News going ‘What the heck, there’s these people and they’re not staff journalists and they’re in Syria? I had no idea that that’s how my news was being made.’”

But the same technology that has allowed more people to report has also compounded the dangers of doing so. While journalists can gather and file news from almost anywhere in an instant, the required tools leave their users exposed.

“You both have surveillance and harassment but it’s also easier for people to pin down where you are and to figure out which journalists they want to get,” Judith Matloff, a journalist and media safety instructor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, said.

Reporters who stay too long in a conflict zone can attract attention and be tracked down. Those who file or tweet live from an internet hotspot are signaling their presence to a potential perpetrator. And the competitive pressures to file live are tremendous. A decade ago, reporters would have waited to leave a region or country to publish their material.

“They would have had a tape and they would have found a human pigeon and sent it back to the office,” Matloff said. “I think about the old days, when I was in Angola in the early 90s, a satellite phone weighed about as much as a coffee table, you couldn’t lift it, you couldn’t carry it. So, you tended not to stay in a super, super remote dangerous place for too long because you had to file.”

Signals from today’s hand-held satellite phones can be readily traced with the appropriate equipment and are thought to be behind the deaths of at least two journalists in the Syrian war.

Marie Colvin, a veteran American correspondent for The Sunday Times who was killed in Homs in 2012, was one of the few remaining reporters in the city at the time. She was horrified by what she saw and wanted to counter the Assad regime narrative.

“She told CNN it was ‘a complete and utter lie that they’re only going after terrorists … The Syrian Army is simply shelling a city of cold, starving civilians,’” wrote journalist Paul Wood in an article about her killing and her family’s lawsuit against the Damascus government. “But according to the Colvin family lawyers, the satellite phone signal from these interviews was located by Syrian Military Intelligence.” Within hours of her report, she was killed by Syrian artillery. French photographer Remi Ochlik was killed in the same incident. In an interview with CNN, President Bashar al-Assad denied his military was involved. Journalists operating in the field had previously expected satellite phones to be unaffected by tracking and surveillance techniques because they do not rely on the local cellular network.

But media outlets are vulnerable to digital threats even when their journalists don’t travel. Websites are subject to traffic floods (distributed denial-of-service, or DDoS, attacks) and other types of warfare from hackers, including those presumed to be hired by governments wanting to silence critical news outlets.

Politically motivated hacking took a new turn in 2016 in Ukraine, when hackers published the names and personal information of about 4,000 journalists, many of whom had reported on pro-Russian separatists in the country’s east. Several reporters whose details were published said they received threats.

Furthermore, in a world where publishing platforms are plentiful and free, journalists are no longer perceived as necessary. All sides to a conflict can Google individual journalists to scrutinize their stories, view video footage, and see a photojournalist’s entire portfolio. According to Haviv, this began as far back as covering the Balkan conflicts in the 1990s: “The advent of, first, satellite TV and the acknowledgement of the power of journalism, specifically imagery to a large extent, became known to the players in that conflict, [and] we went from being considered allies to being either outright enemies or potential enemies.”

“We are a big community; we are worth money. Every kidnapping is about money.”

Jonathan Alpeyrie, photographer

Extremist groups such as Al-Qaeda and Islamic State, also known as ISIS, prefer to publish directly rather than rely on journalists to disseminate their information.

“ISIS has proven that these groups can be more strategic and effective in their messaging than they were previously when they worked with journalists,” said freelancer Anna Therese Day, an FFR board member. “So now journalists are perhaps more valuable as hostages than as messengers.”

Kidnapping for ransom took place well before the most recent Mideast conflicts. In Somalia, for example, it was a lucrative source of income for Somali militias and criminals amid the chaos of the civil war, and several Western journalists who went to write about piracy off the country’s coast ended up as hostages.

But in Syria, more than 100 journalists have been abducted since the start of the war, a number unmatched by any other conflict documented by CPJ. At one point, a journalist was getting abducted in Syria once a week. The unprecedented rate of abductions only slowed as fewer and fewer journalists entered the country.

“We are a big community; we are worth money,” said Jonathan Alpeyrie, a French-American photographer, who was abducted on his third foray into Syria in 2013 and held for 81 days. “Every kidnapping is about money. We’re easy to capture.”

There are no reliable figures on just how much has been paid to ransom journalists. New York Times correspondent Rukmini Callimachi reported in July 2014 that Al-Qaeda and its direct affiliates pocketed at least $125 million from kidnappings between 2008 and 2014. The sum includes all hostage payments, not just those related to journalists. Although European governments deny paying ransom, the Times said kidnapping Europeans had become a global business for Al-Qaeda.

The U.S. and U.K. publicly oppose the payment of ransom, saying it fuels terrorist groups. This stance came under intense scrutiny after it emerged in 2014 that European hostages in Syria who walked free had been held alongside their American and British colleagues who were later killed. Journalist David Rohde, himself a former hostage, pointed out how the differences in the European and American approaches to payment of ransom put journalists’ lives at risk.

According to Jon Williams, managing director of news and current affairs of Ireland’s RTÉ and former managing editor, international news, of the U.S. broadcaster ABC, the changed landscape for journalist safety in the last few years can be attributed to a “combination of the rise of groups with whom you cannot reason and crazy hardline politics of U.K. and U.S. administrations.”

Williams said that even in its previous incarnation as Al-Qaeda in Iraq, ISIS had been open to dialogue through third parties in the kidnapping cases of several journalists in Iraq in the five years following the U.S. invasion. But, he said, this was impossible when governments like those in the U.S. and the U.K. abandoned the “pragmatism of knowing when to look the other way and what questions not to ask” in favor of hostage policies that he describes as “muscular bravado, that I would argue contributed to the loss of U.K. and U.S. lives.” Williams was BBC world editor for seven years before he joined ABC and led its coverage of Afghanistan and Iraq.

The lawlessness that facilitates kidnapping is widespread; militias and criminal gangs are proliferating while the number of states where law enforcement and justice are crumbling, or have disappeared entirely, increases. The Fragile States Index of the U.S. think tank Fund for Peace shows that in huge swaths of west Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, central governments no longer exercise control across all of their territory.

“There are so many regions now where there are not effective governments functioning and so they can do little to protect foreigners, journalists and others, who happen to be in those communities. And that’s becoming a real threat because it allows combatants to operate with a degree of impunity,” media academic Picard said.

In some functioning democracies, like Mexico, journalists are in peril from organized crime. CPJ has documented 26 confirmed journalist killings in Mexico in the past decade, many by drug traffickers or corrupt officials who did not want journalists shedding light on their business. Foreign and national journalists based in Mexico City are largely spared the deadly consequences of reporting on drug lords, but not rural and regional reporters, according to independent journalist and former newspaper editor Javier Garza.

“A reporter’s also vulnerable because when an organized crime group strikes against a journalist, they usually do it without warning, they usually do it without a previous threat, they usually do it when the journalist is unprotected, you know, they can just pick him up on the street and kidnap him, right?” Garza said. “Or they can just show up at his house and drag him out. Or they can just show up at the offices of the newspaper and shoot the building.”

And in some places, government officials are not only negligent they are culprits, according to Jamal Osman, a reporter who has covered East Africa for the U.K.-based broadcaster Channel 4 News. In Somalia, where not one year has passed in the last decade without a journalist being murdered, Jamal said that the militant group Al-Shabaab is the biggest but not the only threat. “There are also politicians and business people who think that the easiest way to get rid of a critic is just to take them out,” Jamal, who also runs the pioneering Somali news website Dalsoor, said.

Even as physical dangers become more prominent, old-fashioned government repression persists, and the risk of imprisonment is rising. Foreign journalists are also subject to expulsion.

“In the last few years, the most high-profile threat has been perceived to be kidnapping,” said Beals, an independent journalist and FFR founder. “But in a recent survey of FFR members they said intimidation or detention by governments or government-like entities was the threat that most concerned them.”

Data from 2016 lends some weight to those fears. The number of journalists killed in the line of duty fell from recent historical highs to 48, although the reasons for the drop are unclear. At the same time, CPJ in its annual prison census identified at least 259 journalists in prison worldwide because of their work—the highest number recorded since the organization began its census in 1990.

Turkey alone was jailing at least 81 journalists in relation to their work. Like several other countries—including Western allies such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain—Turkey uses the cover of fighting terrorism or protecting national security to imprison its critics, squeezing journalists between non-state actors and the governments purporting to fight them.

“One growing threat to journalists is from autocratic regimes being emboldened by the shifting landscape of world powers,” said Day, who was detained for two days in Bahrain in early 2016. “The best example is Egypt … Previously you would say that the U.S. government would have enough sway over Egypt that they would release jailed journalists.”

In four years Egypt has gone from having no journalists behind bars to becoming the world’s third worst jailer of the press, with 25 imprisoned in 2016, many on bogus national security and terrorism-related charges.

All of the journalists jailed in Egypt and Turkey at the time of CPJ’s 2016 prison census were of local origin. Both countries remain a popular base for foreign journalists, but even they are not immune to arrest, expulsion, and violence. In 2014, Egypt jailed several journalists from Al-Jazeera, including Australian Peter Greste, who was eventually deported, and Canadian-Egyptian Mohamed Fahmy, who was eventually pardoned.

Turkey has arrested Western, Syrian, and Iraqi journalists crossing back into the country from reporting trips to Syria or covering clashes in its restive southeast. In addition, at least four Syrian journalists who had fled to Turkey for safety have been murdered there. Islamic State claimed responsibility for the murders.

Mitigating the risks

For more than a decade, Salvadoran journalist Óscar Martínez has conducted in-depth reporting on some of the most sensitive and dramatic stories of the Western Hemisphere. He has hung from trains to interview desperate migrants riding north to the U.S. border; he has spent months living with violent gangs, and has uncovered massacres by the Salvadoran police. He has also received serious threats that extend to his family, and he now lives with safety measures like security cameras around his home and a panic button. But those measures, he says, just allow him to live; they are not the type of holistic safety preparedness that frontline journalism requires.

As a reporter and the manager of a ground-breaking investigative unit Sala Negra (Black Room) at the region’s pioneering online newsmagazine El Faro, Martínez has both received and commissioned hostile environment and first aid training (HEFAT) for his team. “Every journalist should know how to tie a tourniquet or how to detect if he is being followed,” he told CPJ.

HEFAT courses emerged during the Balkans wars when journalists became targets. But it wasn’t until the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s that news organizations began sending significant numbers of staff to learn the basics of trying to stay safe while covering a war or civil unrest, according to editors and safety trainers. The proliferation of boutique companies offering HEFAT training and security advisers to accompany journalists in the field directly tracks the growth in scope and volume of the dangers faced by the media. Many were started by former British military personnel and are based in the U.K.

Paul Burton, a former British army commando, instructs both experienced and rookie journalists in the art of surviving as a conflict reporter. At one of his recent courses, run by the private firm Global Journalist Security, a dozen trainees gingerly walked a course where he hid a pressure plate under dead leaves to simulate a landmine and peppered the landscape with plenty of other surprises.

“What they learn here could save their life, or someone else’s,” Burton said. (Global Journalist Security was founded by Frank Smyth, who is also its executive director. Smyth advises CPJ on journalist safety and was CPJ’s Washington representative for more than 11 years.)

Not all international frontline reporters, let alone local reporters, have access to such training, first and foremost because it is expensive. A five-day residential course can cost $5,000 or more.

Media development groups and charities such as the U.K.-based Rory Peck Trust provide free safety resources for independent journalists and pay for a limited number to attend HEFAT courses. Some training companies and news outlets subsidize training for freelancers either directly or through funding non-profits, but many do not.

“I did go into conflict without training,” said Sam Kimball, a 29-year-old American freelancer who recalls working alone in Cairo because he didn’t know better. “It was scary. I didn’t think it all through,” he said of covering the killing in Cairo’s Rabaa Square in 2013 of supporters of ousted President Mohammed Morsi. “On my next deployment I would do a lot more homework,” Kimball said at the end of a HEFAT course in Maryland.

Day, of FFR, said, “The news industry is increasingly relying on freelancers but not having the institutional capacity to support them in the way that they previously supported staffers in those same contexts. Every industry is turning to contracted labor as a way to cut costs. Journalism is the same but when we are talking about conflict journalism, the stakes are higher than ever for that contract employee.”

International freelancers complain of low pay, late payment of fees and reimbursement of expenses, and a lack of safety awareness among commissioning editors in some established and startup news operations.

“A lot of news organizations don’t pay a different rate for working in difficult or dangerous or foreign environments, where the cost of reporting is high, than they do for sitting in your apartment in Brooklyn writing an article about the new trend in shorts,” Day said.

News companies, both legacy and digital-era, vary widely in their treatment of freelancers, particularly those with whom they do not have a long-term relationship. “There are some who wrap you up in cotton wool … then there are others who just really don’t give a shit as long as you come back with some content,” Beals said.

“When we are talking about conflict journalism, the stakes are higher than ever.”

Anna Therese Day, freelance journalist

Freelancers argue that they will look after their own safety if they are paid enough to secure the training, insurance, and safety equipment. International reporters say rates vary widely, with some U.S. news websites paying $250 to $300 for a story, whereas several British broadsheets pay £60 ($75) for a piece. Newbie still photographers may get as little as $50 for a conflict image. Video material usually commands a higher fee.

Reporters strive to get a commission and negotiate a day rate and expenses, but many who are still seeking to make a name for themselves fall short of that. They end up having to front the costs of an assignment and hope that they can sell the material. But if they are not given upfront expenses, it is difficult to hire the most experienced drivers, interpreters, and fixers in the field. Lack of funds may also lead to inadequate communications and tracking equipment, or staying too long in a conflict zone to save travel money and thereby flagging your presence to potential kidnappers or hostile forces.

Santiago Lyon, a prominent photographer who was vice president and director of photography at The Associated Press from 2003 to 2016, is sympathetic to the problems of freelancers, but he also feels budding independent journalists have to take responsibility for their own safety training and equipment. “The argument that you’ll sometimes hear is, ‘Well, we can’t afford that.’ Well, then I think you have to ask yourself, ‘if you can’t afford it, why are you doing it?’ Because without it, it just raises the risks to the point where they become unacceptable.”

After the Syria beheadings, the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) said it would not accept freelance work. A year earlier, it stopped sending reporters into militia-held areas to dissuade journalists from taking risks. And after the death of its correspondent Colvin in Syria, London’s Sunday Times stopped taking freelance photo submissions. Other outlets followed suit.

Miriam Elder, foreign and national security editor for the U.S. news portal BuzzFeed, does not accept non-commissioned material from war zones. “I don’t want to encourage reckless behavior and I think that taking something like that I can potentially do so,” she said. “I had people write, ‘Hi I am in Syria; Hi I’m in Iraq,’ and I’m like, ‘No.’”

While those policies may hold for some large international news organizations, others are not totally transparent in their dealings with freelancers, according to Beals, who wants editors and freelancers to spell out each side’s expectations and responsibilities in open conversations before anyone ever sets foot in a conflict area.

“If you say to your foreign editors you can’t use any freelancers’ material, then actually, of course, they’re going to, because something’s going to happen, then there’s going to be a chemical weapons attack or there’ll be something, and they want some freelance content,” Beals said. “And they’re not going to be able to be open and honest about the fact that that’s what they’re doing, which means that rather than promoting the kinds of conversations that we’ve all been trying to promote, those [conversations] are going to be hidden and then that’s a problem.”

Experts disagree on whether there has been an increase only in the numbers of freelancers, or also in the level of recklessness in their reporting. Beals acknowledges that some freelancers venture out unprepared and stumble into trouble. But in her opinion, the numbers have fallen. “There may have been the perception there were reckless freelancers five or six years ago. But freelancers are becoming more professional and filling the workforce gaps that mainstream media once filled with full-time staffers,” she said.

After the 2011 death in Libya of photojournalist Tim Hetherington, his close friend and colleague Sebastian Junger founded the New York-based nonprofit Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues (RISC) to teach first aid. Globally, RISC is the only group that currently provides freelancers with specialized battlefield first-aid courses for free. Over the past five years, RISC says it has trained 288 journalists.

Former RISC Deputy Director Lily Hindy estimates that more than half of those journalists received no other safety training. And though RISC has organized workshops in Kenya, Turkey, and Ukraine over the past five years, the vast majority of journalists trained have been Western. The problem, according to Hindy, is that most training firms cannot operate in dangerous areas for liability reasons, and as far as she knows there are no local initiatives that provide the same service. “You need to be able to afford a plane ticket,” said Hindy, “so we are missing some of the most important people.”

Indeed, aside from freelancers, international news organizations are reliant more than ever on local journalists for news and images. But domestic reporters have even fewer safety resources available than international freelancers.

“They basically have nothing,” said Owais Aslam Ali, secretary general of the Pakistan Press Foundation. He said media houses in Pakistan provide little or no safety training or insurance for their reporters and stringers, especially those in the non-metropolitan areas of the country who cover dangerous beats such as the Taliban, the security forces, conflict, and crime.

And while working for an overseas outlet may pay a little better, it comes with greater risk. “Reporting for foreign organizations is generally more dangerous for local stringers as reporting for them pushes the limit a bit more than reporting for national organizations,” he said.

The situation is similar across many democracies with a vibrant press. Journalists generally, but particularly those outside the big media hubs or capitals, complain of poor pay and training.

“There are very few institutional protections,” said Mexican journalist Garza. “Media companies, for the most part, don’t really care or invest in protection measures. Some don’t even invest in protecting their own buildings,” he said.

Getting more people on to training courses is an improvement but journalists themselves sometimes complain that they may not be getting the information they need for the countries or regions where they intend to work. Trainees also complain that some courses are light on information security and counter-surveillance techniques, skills that are increasingly necessary.

“There is just a huge gap between the Western journalists and teachers and the local reality.”

Jamal Osman, Channel 4 News

Osman, the Channel 4 news reporter who started a website focused on Somali news, said that he knows of several organizations that offer safety courses in East Africa. The majority, he said, are taught in Nairobi by trainers with good will but lack of understanding of the safety issues linked to a particular geographic, political, and cultural setting.

“Trainers are always thinking in a Western mentality, talking about drones and things like that. They don’t think about the poor local guys who don’t even have a car to move around in. There is just a huge gap between the Western journalists and teachers and the local reality,” he said. “Better training should consider local practices, politics, and threats. You need to think about practicality and where the journalists work, and think about the local component of safety, or it just doesn’t work.”

In Syria, international media protection and development groups have worked hard to disseminate safety information and organize training for local journalists. Courses, however, need to be held outside the country, and Syrian journalists say they have been available only to the few who can travel. While trainers have expressed concern that workshops have become a revolving door of participants who travel from one to the next, journalists complain that the information and resources are not making their way back into Syria.

According to Kareem Abeed, a Syrian who works with the opposition media group Aleppo Media Center, which has had communication equipment and protective gear donated by international groups, none of the center’s journalists who stayed in Aleppo until its December 2016 takeover by forces supporting Assad had received safety training. “It is impossible to train people who are in Aleppo, even through the internet, because networks are very bad, they are not stable,” he said before the takeover. “And it is very, very difficult for them to come to Turkey.” Instead, Abeed said, these journalists improvised.

Some Syrian outlets with journalists operating inside the country have developed unorthodox protection protocols—such as having only a handful of editors and reporters know the identities of their colleagues—along with change in location and routine, and eventual evacuation outside the country. “Each person uses the information he has to make his own decisions every day,” Abeed said.

While many international journalists did arrive in Syria with basic safety training, they did not have access to comprehensive and timely information about the increasing threat of kidnapping. This meant that some freelancers moving back and forth across the Turkish-Syrian border in particular were operating on flawed assessments of the level of danger. Freelancers without access to news organization security resources, which often include a detailed risk assessment by a safety expert, took their cues from colleagues who were all equally in the dark about Islamic State’s practice of kidnapping Westerners. The media blackouts observed by the families and employers of those who had been kidnapped, in the hopes of quietly negotiating the hostages’ release, made it hard for freelancers to fully appreciate the risks.

“One of the difficulties we face now is that companies that do risk assessment do it on a for-profit basis and so they are selling their services to large media companies and they don’t want to give the same assessments away to individual journalists who might not be paying for it,” Picard said.

Governments also hold intelligence, but they typically do not want to share it with individuals or groups of journalists beyond issuing the usual travel warnings. Such warnings are useless for journalists since they advise citizens to leave or avoid the very areas where reporters need to go to gather news.

To Williams of RTÉ, the most important component of safety for journalists operating in a threatening environment is a full understanding of appropriate processes for when something goes wrong, including identifying “who kicks the machine into action to drag them out” if this becomes necessary.

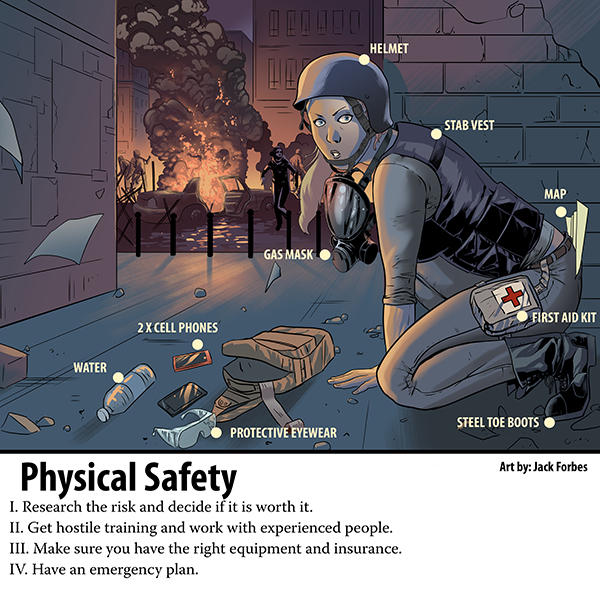

For journalists to stay safe in a conflict zone or a place where violent protests could erupt also requires protective gear. The equipment, like training, is expensive. In the U.K, where many frontline freelancers are based, an industry norm flak jacket with plates costs approximately £700 ($875).

Even when journalists have the gear, some governments impose restrictions on the importation of so-called personal protective equipment (PPE), such as helmets, body armor, and gas masks. Countries such as Egypt and Thailand, where governments are actively fighting insurgencies, say they are trying to prevent such equipment from falling into the wrong hands. Though restrictions may not have been put in place to intentionally prevent journalists from safely doing their work, their imposition on foreign and local reporters puts them in seriously dangerous situations.

In Egypt, for instance, only military personnel are legally allowed to carry body armor, including bullet-proof vests and protective helmets, as well as satellite phones and other types of telecommunication devices. Failing to comply can result in a military trial and prison. Freelancers who cover the Middle East said they have routinely had their personal protective equipment confiscated by airport authorities when traveling through Egypt, causing weeks of delays as they have gone through the lengthy bureaucratic process of getting it back.

Local journalists, meanwhile, are forced to improvise, using motorcycle helmets to protect against bullets while covering violent clashes. On at least one occasion several journalists were targeted by protesters while using military bullet-proof vests that the Ministry of Interior had handed over to the local syndicate following a spike of violent attacks against journalists, according to an Egyptian freelancer who asked not to be identified for fear of persecution. The vests, which did not clearly identify the journalists, put them at more risk.

In Thailand, where two journalists have been shot dead since 2010 while covering political unrest without adequate gear, safety equipment is considered a weapon that requires a license under the country’s Arms Control Act of 1987. In August 2015, Hong Kong photographer Hok Chun Kwan was briefly detained at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi airport for carrying protective body armor. Though the government eventually withdrew the charges against Kwan, if convicted, the journalist could have faced up to five years in prison.

Solidarity, knowledge, and protection

Even if journalists could get the right safety training and equipment, this wouldn’t be enough to keep them safe, according to Salvadoran investigative journalist Martínez, who not only travels to dangerous places like many Western freelancers, but also lives in danger in his home in San Salvador. A HEFAT course, he said, should be only a part of a reporter’s safety toolkit. “None of this training is going to matter if [the reporter] is taking unnecessary risks by not knowing how to work with a sensitive source, or how to handle sensitive information. Too many journalists want to run before they can even walk.”

Martínez has made it his main concern to ensure the safety of the reporters with whom he works. The investigative unit Martínez runs, Sala Negra, not only gives all of its reporters the practical knowledge of HEFAT training but requires that they work in teams, and take the necessary time to fully understand each situation before going out into the field. They must map sources, know local players, and acquire a thorough understanding of risk.

Martínez said this kind of approach is rare not only in Central America, but also among the international journalists with whom he has worked. Without a doubt, he said, the most vulnerable reporters are the locals, who lack training or the backing of a media organization. But internationals who are not fully prepared are also at risk. They may have more training and financial resources but they are not safe if they don’t have a full grasp of the story that they are covering.

Martínez said that in Mexico, where he covered organized crime for years, owners and editors often send journalists without investigative or organized crime experience to cover this extremely dangerous beat.

“I know of photographers who one day were shooting a soccer match and the next they were sent to cover organized crime,” he said. “A reporter covering those types of stories needs to be an expert. He needs to be able to comfortably read the signs.”

In response to such risks, one group of Mexican journalists came together to raise journalism standards and morphed into something greater as drug cartels and other organized crime unleashed their fury on investigative reporters.

Founded in 2007, Periodistas de a Pie (Journalists on Foot) set out to improve the quality of reporting and editing nationally. But the organization’s workshops drew local reporters from states ravaged by cartel violence. The group began organizing workshops on safety protocols for journalists reporting in conflict zones, and inviting experienced journalists to address their meetings. It soon became an important source of support for colleagues in danger. Affiliated networks were later formed in cities including Juarez, Chihuahua, and Guadalajara.

Journalists working together in such networks can have a strong effect on safety. In Pakistan, where the media is subject to threats and violence from all sides, journalists banded together in a group called Editors for Safety, vowing to report on and highlight attacks on the press in an attempt to spur the authorities and their own employers into action.

“Editors and news directors of leading television networks have started giving top priority to covering attacks on media as breaking news, and this has raised the level of immediate response by authorities,” Aslam Ali said.

“However, media organizations still do not follow up cases of murders, killings and other cases of violence on a long-term basis with authorities and the courts … Media organizations have made no efforts to pressurize non-state actors, even though these non-state actors use the media to project their viewpoints,” he said.

Protection mechanisms are most likely to succeed when they achieve the trifecta of journalists, security services, and civil society. That was the winning combination for Colombia’s Program for the Protection of Journalists and Social Communicators, which was set up in 2000 when the country was a killing field for the press. Between 1992–when CPJ began tracking journalist deaths worldwide–and 1999, at least 23 journalists were killed for their work.

“I know of photographers who one day were shooting a soccer match and the next they were sent to cover organized crime.”

Óscar Martínez, Sala Negra

The program has investigated 1,300 cases of threats and attacks on journalists, said Pedro Vaca, executive director of the local Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa (FLIP). Seventy percent of those journalists have received protection services, which range from emergency evacuation to 24-hour armed bodyguards to the use of armored vehicles for transportation.

The government is solely responsible for the implementation of security measures, but from the onset, the protection mechanism has also included members of civil society in the investigation and decision-making processes. “There is no doubt that the participation of civil society in this process is what makes it work,” said investigative journalist Gonzalo Guillén, who has been provided with bodyguards for the past five years.

However, the program has come under increasing criticism in recent years. According to Vaca, structural reorganizations to include more government representatives have complicated decision-making processes and slowed down the delivery of safety measures. Additionally, he said, the program has moved from providing mostly financial assistance for emergency relocation to providing armed guards and armored vehicles. This move, which Vaca says allows journalists like Guillén to continue reporting, has also increased the costs of individual protection 15-fold. And with growing budgets, the program has been plagued by corruption and expenses that cannot be justified, according to FLIP’s analysis. Sindy Cogua, the program’s assistant director, told CPJ that in response to an investigation into such claims, the program has taken steps to prevent corruption.

Most importantly, Vaca criticizes Colombian authorities for lacking in two areas: prevention and justice. Vaca says it is not enough for the government to provide protection; it should also be working on projects that promote safety awareness among the journalists and officials with whom they work. Above all, Vaca believes that criminal investigations and legal proceedings against those who threaten and attack journalists are crucial to the program’s success. In 2015 the program reviewed 300 cases and saw one conviction, despite having the support of representatives from the attorney general’s office. In response to this criticism, Cogua said the program is by law charged only with protection, and investigations must be conducted separately.

In any case, journalists who receive support say that it is indispensable. “This program is the only reason that I have been able to continue working, investigating and reporting,” said Guillén. “Without the protection they provide me I would not be telling this story, any story.”

Though similar protection systems are in place in Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico, Colombia’s is the only one to have made a real difference in preventing deadly attacks.

Elsewhere, the response to the growing dangers for journalists, coupled with an increasing reliance by international news outlets on freelancers, has led to the creation of several groups focused on improving media safety.

Three years ago, Beals was among a handful of independent journalists who set up FFR with the aim of opening lines of communication with news organizations and showing the outlets that “we were not reckless freelancers with iPhones running around Libya,” but were professionals and should be treated as such.

Industry engagement with FFR and others helped lay the groundwork for another initiative dedicated to saving journalists’ lives–the ACOS Alliance, which stands for A Culture of Safety.

In the wake of kidnappings, some in the media industry decided they must change their approach to sending freelancers on dangerous assignments. Soon a small group of U.S. editors began talking about drawing up a set of safety principles and best practices, and this group was eventually expanded to include freelancer and press freedom groups, including CPJ, and journalism schools. The resulting principles were launched in February 2015 and formed the basis for what would become ACOS.

“Without the protection they provide me I would not be telling this story, any story.”

Gonzalo Guillen, investigative journalist

Many news organizations, including the main international wire services, U.S. television networks and the BBC, have signed the ACOS principles and more have been asked to do so. Companies pledge to treat freelancers working in conflict zones in the same way they would treat staff. For their part, freelancers undertake to do safety training and planning, and have the necessary safety equipment and insurance.

In order to reach an agreement, the journalists, news executives and press freedom groups that founded ACOS made the principles voluntary. This has not satisfied some freelancers.

“The most troubling trend that freelancers see with ACOS is that it is not binding,” said freelancer and FFR board member Day, who accuses some news outlets of continuing to pay poorly for independent work. “That it is a year later and while our members have been working with our nonprofit partners to fulfill our side of the obligations, which is hostile environment training and better professional preparation, that’s very difficult with the given pay of the industry. While on the industry side all they needed to do was walk down the hall to their finance and legal departments and that hasn’t been done yet.”

BuzzFeed provides training and equipment for its regular freelancers and expects occasional freelancers to take care of those things on their own. It works with ACOS but has not signed the principles, preferring for now to focus on building its internal journalist safety structure, Elder said.

“I do think news organizations have a responsibility for making sure that these important stories are reported out in a way that not only brings information to our readers, but also is done in the most responsible way and the safest way for the reporters,” Elder added.

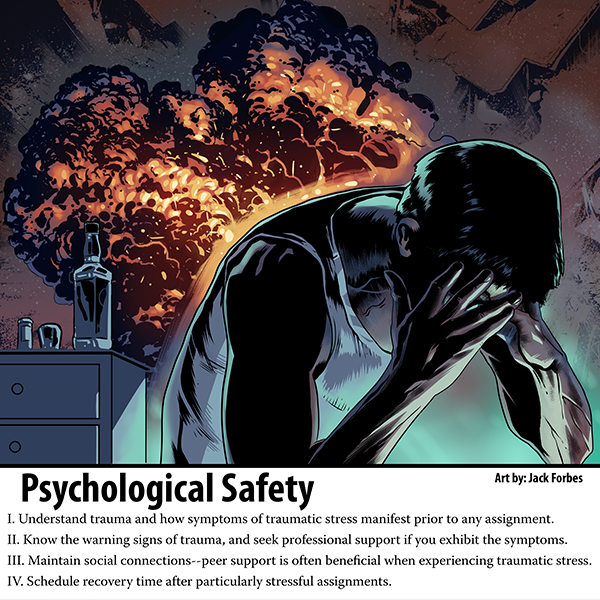

Trauma and mental health

Along with the need for better resources has come awareness of post-traumatic stress and other psychological injuries among frontline journalists. Over the past decade, reporters have become more willing to talk about the impact that their job has on their mental health. That awareness has grown even faster since the Foley and Sotloff murders, said Sarah Giaziri, Middle East and North Africa program officer at the Rory Peck Trust, which supports freelancers worldwide.

The impact on mental health as a safety issue that affects all journalists, and not just those reporting from a battlefield, began to gain more momentum as editors working far from conflict zones spoke of the heavy toll that the non-stop flow of violent images from Syria was having on them, according to Emmanuel Serot, AFP’s editor in charge of safety and security.

But as the Syrian conflict spilled into Europe with the refugee crisis, Serot said, more and more reporters covering the story from Greece, Bulgaria, and Germany, their home countries, began to speak emphatically on the issue. These journalists, many of whom were previously deployed to conflict zones, said they were simply unprepared. “If you go to Syria, to Iraq, you are prepared,” he said. “But this story became so disturbing because it was the first time that they were not able to stay as journalists, that they had no choice but to put down their camera and help.” The impossibility of keeping professional distance when seeing people on rafts who needed immediate help was the turning point, Serot told CPJ.

Serot added that younger reporters are quicker to identify the issue. They are also quicker to ask for help, not only in terms of better mental health resources, but also in terms of general safety.

In the global south, the psychological toll on journalists reporting difficult stories is not as frequently acknowledged, let alone treated. Afghan freelancer Mirwais Jalalzai, who has reported for national and international outlets, said he has been reprimanded on multiple occasions by editors. “They said my stories, especially those focused on the victims, showed that I was emotionally affected and that this was not a good way to write, but they didn’t help me,” he said. “They just didn’t know how to help.”

Jalalzai said he, like many of his peers, has trouble sleeping because he can’t shake disturbing images out of his head. “All of my Afghan journalist friends are mentally sick,” he said. “Our lives are all about covering dead bodies, conflict, and threats. Every day. So, we are not in a healthy position.”

One positive change, though, is that reporters are more willing to talk among themselves about the issue, said Jalalzai, who was among a group of Afghan journalists to participate in a 2016 one-week workshop on trauma organized by the nonprofit Internews. He said he and his colleagues have identified a collective need for additional support, and that he believes any training in this field should be extended to editors who oversee their work.

According to Giaziri, from the Rory Peck Trust, journalists today are not only looking for better therapeutic solutions, but also for improved options for mental health provisions before being deployed. These include training sessions to raise awareness prior to exhibiting signs of trauma as well as integrating mental health into risk assessments.

“Our lives are all about covering dead bodies, conflict, and threats. Every day.”

Mirwais Jalalzai

Giaziri said the need to integrate psychological preparedness became clear to her after working with a freelance reporter who had recently returned from Syria. War reporting was not new to this journalist, who had previously worked in Afghanistan and Libya. But after Syria, where a hospital he visited was blown to pieces shortly after he left, the journalist began to experience frequent blackouts and severe panic attacks, which led him to seriously question his own judgment in situations of stress.

“Freelancers often don’t work alone,” Giaziri said. “They are photographers or reporters who work with each other, and need to trust the judgment of the people they are with. So really, a mental health check needs to be the very first step toward safety.”

But psychological safety preparedness is not often taken into account. Martínez, whose primary concern is his reporters’ safety, said the preventive training provided by El Faro does not include a mental health component. Instead the paper encourages journalists to seek professional support if they feel affected by a story, he said.

However, there is general consensus among journalist support groups and safety experts that journalists on dangerous assignments need access to services that are better integrated.

“You should never look at anything in an isolated way, everything is contextual to the system we are working in–all these sectors are connected and they influence our safety,” said Yvette Alberdingk Thijm, executive director of the international organization WITNESS, which trains and supports people using video in their fight for human rights. “If the person doesn’t have the [mental health] resources and the support to do their job, they will ignore risk and physical security.”

Alberdingk Thijm believes safety should be approached as an ecosystem made up of physical safety, digital safety, and health. Each component, she says, influences the others and helps with a more holistic integration into daily work. Others echo the need for a “trifecta approach,” as Giaziri calls it. “Missing any of the different parts just compromises general safety,” she said.

Consequences beyond journalist safety

The new risk landscape poses a threat not only to journalists but to journalism. As photographer Haviv said, news organizations that can’t get reporters to a place are dependent on content, particularly visuals, provided by the combatants themselves or other activists.

“Srebrenica, if it happened today, would happen live on GoPros [wearable cameras] attached to the paramilitaries,” Haviv said, referring to the 1995 massacre of the Bosnian war. “And [commanders] would be giving a YouTube press conference to a Serbian paramilitary journalist.”

Many traditional media companies say they do not take on-spec stories or material from sources they do not know. But the sheer number of news sites today means that unverified content will see the light of day.

“So this is also another very, very brutal change, and I think that it makes our jobs much, much harder,” Haviv said. “In a sense, it takes the ability to really try to find within these groups, or around these groups, people that understand the value of legitimate journalism, which is becoming more and more difficult as journalism itself is saying, ‘Well, we don’t really care if it’s coming from illegitimate journalists, because we’re going to publish it anyway.’”

Lyon, formerly of the AP, agreed. With fewer news organizations willing to risk putting staff in harm’s way in Syria and parts of Iraq, “the flow of information comes from partisan sources instead,” he said. This type of content from conflict zones is hard to verify independently. “It’s really worrisome in this day and age when journalistic credibility is being called into question and false news is being injected in the social media feeds of people and sold as news,” he said.

In the Middle East, the reliance on unverified or partisan sources gets deeper with each year of conflict, because it is simply too dangerous for journalists to remain. And even outside of conflict zones, journalists who have fled are not safe.

Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently (RBSS), a collective of citizen journalists that reports from within the Islamic State stronghold of Raqqa, is one of the groups whose safety scheme relies heavily on the anonymity of its reporters not only to their public but within the group itself. According to Abdel Aziz al-Hamza, the group’s co-founder and spokesperson, RBSS’s commitment to anonymity extended to a digital safety training the group conducted in 2014 outside Syria in response to the murder of one of its reporters. At the time, each group member left the country and was trained alone in order to secure their anonymity and allow them to return and continue reporting, al-Hamza said.

Three years later, the group still relies on that initial safety plan. “Nothing has changed and this system is still working for us [inside Syria],” al-Hamza said from Berlin, where he now lives.

However, RBSS members outside Syria are vulnerable. “We are being targeted outside more than inside because ISIS has found no way of finding us inside,” he said. “There is more information about those who are outside. We have photos and details that are published about us and that is how they find us.”

At least two journalists affiliated with RBSS were tracked down and killed in Turkey in the past two years. Faced with this heightened risk, al-Hamza said, RBSS was forced to fall back on an old technique: the group’s reporters and managers have left Turkey, and now live in small, isolated communities in Europe, far from other Syrians.

Journalists from Colombia to Bangladesh all echoed the notion that the most reliable safety protocols for at-risk journalists are emergency evacuations, which are most commonly bankrolled by international groups or Western governments. Though physically safe, journalists forced outside their home countries struggle to continue to work. CPJ research shows that only a quarter of journalists in exile continue to practice their profession. And for each journalist who flees, that is one less person gathering and disseminating news to inform the public at home.

Lessons learned

The response to the soaring dangers may not be adequate and it is certainly not spread uniformly around the globe. But safety experts and journalists can point to improvements over the past decade.

First is simply the acknowledgement within news organizations that safety is an issue. This may sound modest, but international journalists over 40 years of age are not short of anecdotes about being sent with nothing but a pen and notebook to cover a war or street protests. Most news organizations were not equipped to deal with safety in a systematic way. That has changed. The bigger organizations have dedicated security teams and direct channels, bypassing the normal news management structures, for teams on the ground to contact editors in charge of safety. They also provide staff with training and equipment, insurance, and counseling when they return from deployments.

Second, journalists themselves, whether staff or contract hires, are more aware of risk and are demanding the means to ensure their own safety.

Third, cooperation among journalists has increased and fewer local reporters in dangerous areas are working in isolation.

“I think the networks are stronger now than they were 10 years ago, and even stronger than five years ago,” safety expert Matloff said. “People are working together more and I think that’s absolutely critical. And we saw that in Mexico.”

Fourth, media safety and the flagrant disregard of authorities for justice in the killing of journalists have been taken up by international bodies such as the United Nations. The U.N. Security Council adopted two resolutions in 2006 and 2015 on journalist safety and the protection of civilians in armed conflict respectively; and the General Assembly has passed numerous resolutions on impunity in the killing of journalists. These and other efforts, such as UNESCO’s journalist safety mechanism, may not have directly saved many lives, but they are a step on the road to improved protections.

Fifth, U.S. authorities have taken steps to better address hostage situations, including the setting up of a Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell to coordinate the multiple agencies from the FBI to the State Department that work on hostage-takings. It also stated that families who tried to raise ransom payments or who engaged with kidnappers would not be prosecuted, after the Foley family revealed they had been threatened with prosecution by a U.S. official when they tried to gather ransom money to free the journalist. The government did not change its policy of refusing to pay ransom but that policy is now under intense scrutiny.

And sixth, the spate of kidnappings in Syria stirred a debate among journalists about the widespread news industry practice of keeping news of journalist abductions from the public while often reporting on the kidnapping of non-journalists. More than 100 journalists have been abducted in Syria since 2011 and about 25 are still missing. At one point in 2013 media blackouts hid the scale of the kidnappings, particularly of foreigners, not only from the general public but from inexperienced reporters contemplating venturing into Syria. Most outlets and press freedom groups still respect requests by families or news organizations not to report on abductions at least in the initial stages of a kidnapping when publicity could be harmful. Nevertheless, the reasons for such requests receive greater scrutiny.