As killings of journalists in Pakistan decline so too does press freedom, as the country’s powerful military quietly, but effectively, restricts reporting by barring access, encouraging self-censorship through direct and indirect acts of intimidation, and even allegedly instigating violence against reporters. Journalists who push back or are overly critical of authorities are attacked, threatened, or arrested. A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Documentary: Acts of Intimidation

Published September 12, 2018

Islamabad

The near-fatal attack on investigative journalist Ahmad Noorani last October stood out for one reason: its brazenness. Assailants trailed Noorani’s car for miles before attacking him with a tire iron on a busy Islamabad street. The journalist, who covers sensitive political issues that often involve the military, was saved only through the intervention of passersby. The attack followed a pattern all too familiar to Pakistan’s press. Nearly a year later, no arrests, just silence and an unmistakable message that those who report critically on sensitive subjects, including the military, the courts, or religion, should tread carefully.

The deterioration in the climate for press freedom in Pakistan accompanied a reduction in murders and attacks against the media. Journalists and press freedom advocates say the two trends are linked, with measures the military took to stomp out terrorism directly resulting in pressure on the media. Privately, senior editors and journalists say that conditions for the free press are as bad as when the country was under military dictatorship, and journalists were flogged and newspapers forced to close.

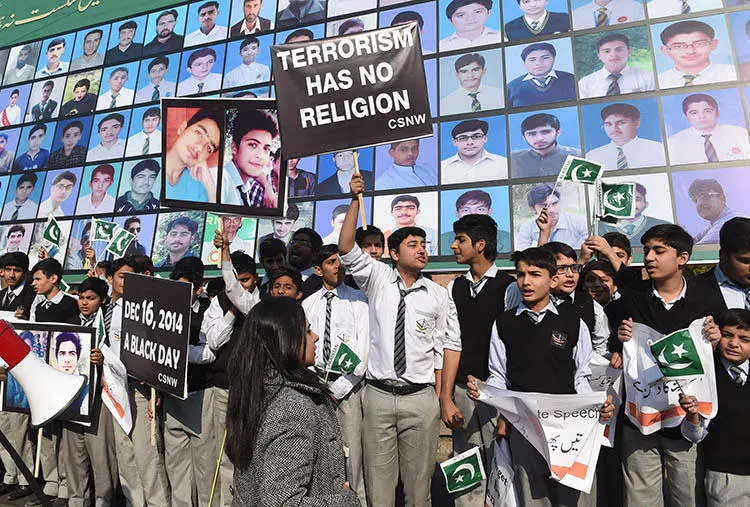

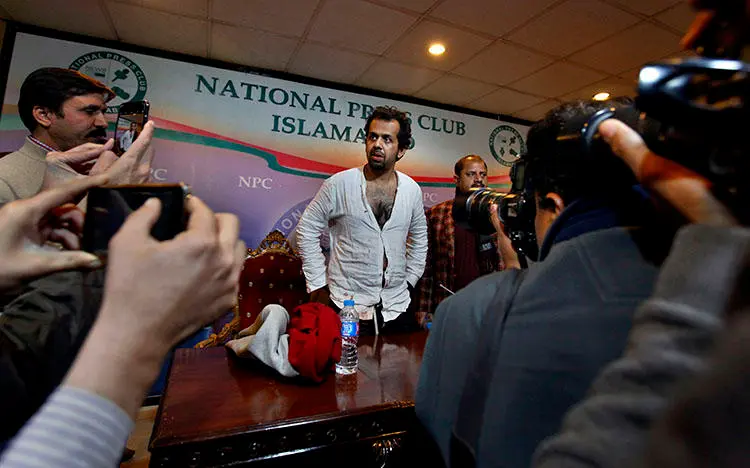

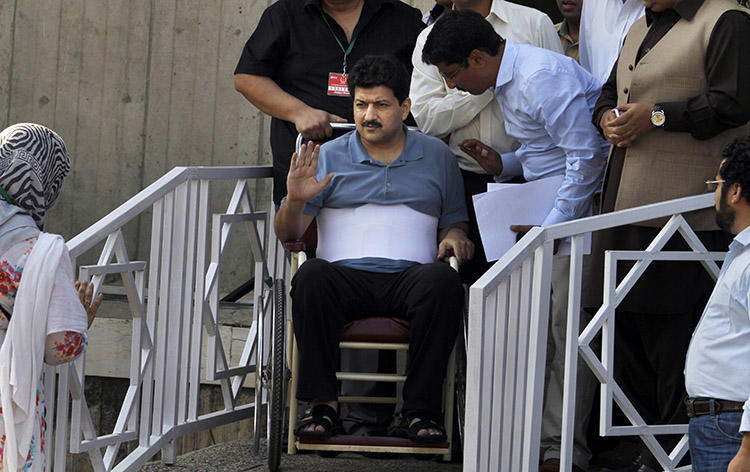

When CPJ traveled to Karachi, Islamabad, Peshawar, Lahore, and Okara earlier this year, journalists, including freelancers and those from established media companies, painted a picture of a media under siege. Many traced the changes to two events in 2014: a shooting that injured Geo TV anchor Hamid Mir and led to a fallout among media groups and with the military, and the aftermath of a terrorist attack in Peshawar that left over 130 students dead.

The military garnered widespread praise for its crackdown on militancy after the school attack, which resulted in a sharp decline of terrorist incidents—and in turn, violence against journalists. Yet the stepped-up activity put the military in position to exert even greater control.

The military already wields influence and power in Pakistan, where it is deeply embedded in society, as well as the country’s economic and political systems. The armed forces are seen widely as an effective institution that holds the nation together, and offers protection. To the east, Pakistan faces India, a far larger and powerful neighbor that is considered hostile, and with whom it has a territorial dispute over Kashmir. To the west is Afghanistan, unstable and with a porous, mountainous border that creates obstacles to security. Internationally, the U.S. has used Pakistan as a staging area for operations in Afghanistan, even as it launches drone strikes against militants on Pakistani territory—an issue of nationalist ire.

While the military submits to the formalities of civilian rule, it sees itself as a bulwark against what some view as the chaos of democratic politics. But it remains sensitive to criticism or allegations, such as its apparent support for terrorist groups in neighboring countries, including the Afghan Taliban and Lashkar-e-Taiba, which is accused of staging the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack.

The military has quietly, but effectively, set restrictions on reporting: from barring access to regions including Baluchistan where there is armed separatism and religious extremism, to encouraging self-censorship through direct and indirect methods of intimidation, including calling editors to complain about coverage and even allegedly instigating violence against reporters.

The military, intelligence, or military-linked and political groups were the suspected source of fire that resulted in half of the 22 journalist murders in the past decade, according to CPJ research. Hence it is easy to see how the military’s widening reach is viewed as a source of intimidation. The military has clashed with Pakistan’s elected government, which tried and ultimately failed to assert civilian control. Journalists find themselves in the middle of this battle, struggling to report while staying out of trouble.

Issues including religion, land disputes, militants, and the economy can all spark retaliation—and laws such as the Pakistan Protection Ordinance, a counterterrorism law that allows people to be detained without charge for 90 days, are used to retaliate against critical reporting. Female journalists must navigate additional pressures when reporting in religiously conservative areas, such as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or rural districts.

A detailed request for comment on this report, emailed to Major General Asif Ghafoor, spokesman for the armed forces, was not answered. General Ghafoor earlier did not respond to a request for a meeting. A scheduled interview with the then information minister in Islamabad was cancelled at the last minute by the government.

With high-profile attacks, like the failed assassination of Geo TV’s Mir, journalists say they are often forced to play it safe by toning down or avoiding controversial but newsworthy stories. Sometimes, as Noorani found, even the briefest lapse in security can expose a journalist to near-fatal consequences.

Noorani, who writes for the daily paper, The News, admits he made a mistake before his attack. For the first time in years, he said during an interview in Islamabad, he used an unencrypted phone line to make an appointment for the next day. Usually he uses an encrypted app to prevent others from eavesdropping on conversations. Somebody, he doesn’t know exactly who, must have been listening in, he said.

When Noorani started off on a 12-mile (20 km) drive from his home on October 27, windows down on a pleasant day, neither he nor his driver noticed the motorcycles tailing the car. When the car entered one of the few stretches along the route with no video surveillance, one of the motorbikes pulled in front of the car and stopped. Noorani’s driver tried to maneuver away, but one of the motorbikes spun faster around the car and, at roughly 25 miles per hour, the rider stretched through the open window, and grabbed the ignition key, forcing Noorani’s car to stop.

It was then, Noorani said, that he made his second mistake. Seeing what he thought were a few harmless teenagers whom he took to be students, Noorani stepped out of the car. The apparent students attacked him with knives, cutting him on the back of his head. One took a hard, well-aimed swing to his left temple with a tire iron, knocking Noorani to the ground. Only the intervention of construction workers interrupted the attacker, poised for a second blow to the head in what doctors told Noorani would likely have killed or incapacitated him for life. His attackers fled. Noorani spent four days in hospital. His driver was also injured.

Who attacked Noorani, and why? Like so much else that happens to journalists in Pakistan, precisely identifying culprits isn’t easy. The police investigation, said Noorani, turned up nothing aside from evidence that the attack was well-planned. And yet, the answers come swiftly from journalists and others whom CPJ asked about the attack: “the establishment,” “the deep state,” “the powers that be,” or, from the more brave, “the military” or even “the ISI”—Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence agency.

***

Pakistan has had multiple military coups though, nominally, today it’s ruled by an elected civilian government. The previous government, led by the Pakistan Muslim League—PML-N—failed to win re-election on July 25, with its leader, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sherif, jailed on corruption charges just before the vote. Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), won a plurality of seats and he was sworn in as prime minister on August 18, heading a coalition government.

Pakistan’s constitution guarantees freedom of the press and access to information, and the country has a large and robust media industry, including extensive privately held broadcast news. And yet, as CPJ found, true press freedom is elusive. While the military is not solely responsible for the pressures facing the media, its hands can be found almost everywhere.

CPJ’s 2013 special report on Pakistan found near complete impunity after a multi-year spike in the murders of journalists, along with an increase in terror attacks. While impunity remains an unsolved issue—Pakistan has appeared in every annual Impunity Index—CPJ research shows that fewer journalists are being killed in retaliation for their work.

Journalists and press freedom advocates said the decline in press violence came after the military’s swift response to the December 2014 attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar, when gunmen affiliated with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan or “Pakistan Taliban,” an Islamist group that shares an ideology with, but is separate from, the Afghan militants, killed over 145 people, including 132 students.

The army launched attacks in militant-controlled areas. It also set up paramilitary forces, including the Rangers in Karachi, which was hit by violence associated with the secular political party, Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) or the Frontier Corps, in the western provinces of Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The MQM is accused of carrying out attacks on journalists, with police in 2011 saying they suspected it of being involved in the murder of Geo TV’s Wali Khan Babar—a claim the group denied. “There is no more pressure on us from the MQM,” a senior newspaper editor in Karachi, who asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the topic, told CPJ. “That has gone.”

While a drop in the murders of journalists is good news, the threat of attack remains. Many journalists and editors said a widespread sense of intimidation has led to self-censorship on issues that may provoke government officials, militant groups, religious extremists, or of course, the military.

During a conversation in Islamabad, Iqbal Khattak, founder of the journalist safety group Freedom Network, said threats to journalists haven’t gone away, even if the source and character has evolved. “If you look at Karachi,” he said, “there was a political party which was accused of intimidating, harassing, taking journalists … away. This threat has been significantly taken out and the force that took this threat out is itself now a threat to journalists and the media houses.” This phenomenon, he said, can be seen across the country.

Owais Aslam Ali, secretary general of the Pakistan Press Foundation, a non-profit training and advocacy group, said that a more cautious approach to covering sensitive topics—essentially self-censorship—accounts for much of the reduction in violence. Ali, who has led the foundation since 1992, said that the long, slow march toward greater press freedom in Pakistan has gone in reverse over the past four years.

The underlying reason for caution is often fear of retaliation as the military exerts control and seeks to retain its influence and position under civilian rule.

Consequences are harsh for journalists who attempt to push back.

In October 2016—days after Cyril Almeida, a columnist for the English-language daily, Dawn, wrote about a clash within the Cabinet between leaders of the then ruling PML-N party and the military—the journalist’s name was added to the “Exit Control List.” The list, maintained by the Interior Ministry, contains names of individuals barred by authorities from leaving the country.

Almeida’s report—known as the “Dawn leaks”—described how the government warned the military that Pakistan faced international isolation unless it cracked down on Islamist groups accused of attacks beyond its borders. The report said that the prime minister’s younger brother Shahbaz Sharif, the then chief minister of Punjab province, accused the military of working to free militants arrested by authorities.

The military’s reaction to the article, which exposed behind-the-scenes activities that it routinely denies, was fierce. “The military said, ‘You have undermined our position by leaking the contents of that meeting,’” said Zaffar Abbas, as he sat behind his desk in a large but spare office at Dawn’s headquarters, beneath a framed edition of the paper’s reporting on the 1947 birth of Pakistan.

A committee of inquiry composed of military and civilian officials, acting through the Ministry of the Interior, recommended that the All Pakistan Newspapers Society—an independent trade association with power to impose fines and bans—take disciplinary action against Dawn, Abbas, and Almeida. No action was taken, and Dawn never divulged the identity of its source, even as two cabinet ministers and a senior civil servant lost their jobs over the “leak” of information the government claimed wasn’t true.

“The Dawn leaks story persists because the military-civilian conflict has not gone away,” said Abbas.

Indeed, the military has hardly disguised its contempt for Sharif or the PML-N over his administration’s efforts to impose greater control over the military which, under the constitution, answers to the elected government.

Noorani’s investigative reporting delved into this tense relationship. Subsequent to the Dawn story, then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif came under Supreme Court scrutiny over alleged corruption. The leader was later stripped from office and banned from politics for life after the court ruled that he was unfit to hold office. In a series of stories in June and July 2017, Noorani cast doubt on the integrity of the process that produced evidence for the court.

While he never directly accused the military of wrongdoing, Noorani said that members of the military phoned him to express their displeasure. “I just asked them to point out factual errors,” said Noorani, adding that they failed to do so. Sensing an increasingly tense atmosphere three weeks before he was attacked, Noorani halted his reporting and signed off from Twitter.

“Most important people know who was behind my attack,” said Noorani, who refers to his assailants as being backed by “the establishment.” The attack, he said, “was a clear message to the media, that all the journalists who are critical of certain wrong things in the establishment, if anyone crosses the red line, if they will write the truth, they will have to face the same consequences.”

Noorani has returned to work, but for the time being is staying away from heavy-hitting stories.

****

Even covering sensitive issues seemingly unrelated to what Noorani referred to as “the establishment” can result in retaliation.

“The mindset now is to control the total narrative and reduce the diversity of opinion, so anything that is going against their narrative, they see as a threat,” Azhar Abbas, managing director of Geo News, said as he discussed the attack on Noorani with CPJ in February.

[Azhar Abbas is the brother of Zaffar, whom CPJ also interviewed for this report.]

Which helps to explain the case of Fawad Hasan, who was threatened over his reporting on labor issues and attacked over his coverage of a leftist political leader.

With his long hair, wispy beard, earrings, bird tattoos on his neck and bangles on his arms, Hasan comes right out of central casting for the role he’s chosen: young, idealistic, leftist, and aiming—through his journalism—to help right the wrongs of the world. “This goes hand-in-hand: journalism and activism,” Hasan said in a Karachi hotel. “I learned some basic skills, for example, how to report, how to be unbiased, how to be impartial when you are reporting, how to write in a way that people do read it.”

He wrote for established newspapers and magazines including the Daily Times and Dawn Images on issues such as minorities, people with disabilities, the harassment of women, and “disappeared” people.

At The Express Tribune, he pushed into a new topic: labor. Hasan started with an exposé of alleged labor law violations by the Pakistani clothier Khaadi. He followed up in October 2017 with a report on labor practices by foreign companies—a sensitive issue in Pakistan as the country tries to encourage more foreign investment.

The story has since been removed from the Express Tribune’s website. The Express Tribune did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment, sent via WhatsApp, about why the story was removed.

Shortly after the report was published, a friend of Hasan’s who was previously detained, warned that the ISI was after him.

Then, on December 29, 2017, two motorcycles, followed by a car, tried to block Hasan’s motorbike on the streets of Karachi. Hasan managed to speed away. After hiding out for three days (when his ever-active Twitter account went silent) Hasan said he met with an officer who showed him a dossier the agency kept on him. “[He] told me very clearly, ‘If you dare write again, we’ll break your head,’” Hasan said. The officer told Hasan writing on labor issues amounted to “anti-state” activity. “He was being very decent, but still I was very much scared,” Hasan said, adding that he agreed to stop writing about the issues.

Labor issues weren’t the only sensitive issue Hasan was covering. While at Karachi University, Hasan studied with Hasan Zafar Arif, a leftist professor of philosophy and deputy convener of the MQM’s London faction. Hasan wrote a feature about Arif when he was released from six months in jail over charges relating to the party’s outlawed leader. When Arif died in suspicious circumstances on January 14, Hasan attended a memorial with the intent of writing a story.

As Hasan was leaving, two men in plain clothes told him to come with them. Hasan said the men threatened him, but promised not to hurt him, so he followed them to a building on the campus which is controlled by Sindi Rangers, a paramilitary group deployed by the army to end militant violence in the city. After a few minutes, the men placed a hood on Hasan, and more people entered the room and began to beat him. Hasan said they told him, “Now we’ll put a stick inside your ass and it will come out of your mouth. Now we’ll teach you a lesson,” and “You are against Pakistan, you are against [the] Pakistan army.” Hasan said he insisted he was merely a journalist.

Fortunately for Hasan, a friend noticed he had been taken away and mobilized a campaign on social media. Twenty or so students created a ruckus outside the campus house Hasan was taken to. After an hour or so, the group whom Hasan said he believes were Rangers released him—frightened and bruised, but not seriously injured.

The Rangers did not respond to a request for comment submitted by CPJ via their website.

“Fawad was picked up obviously for speaking against the deep state,” said Mubashir Zaidi, who anchors the talk show “Zara Hut Kay” (A Little Different) on Dawn TV—part of the same media group that owns Dawn—and who helped mobilize help for Hasan. Zaidi said he advises younger journalists to be more careful about what they write or say. It’s advice that Hasan says he has taken to heart, at least for the time being.

“A lot of people offered that I move to another country, you know, to save my life,” said Hasan, who currently works for the online magazine Cutacut. “I want to stay in Pakistan … This constant fear that if you say this, if you write this, then you will get into trouble, this has to go.”

“I had just told them that if you find something disturbing from my side, just let me know. Just call me up. Don’t pick me up,” Hasan said. “I don’t want to get disappeared like this. If you think that these articles are anti-state, then let’s talk it out.” But, he admits, “If they want to pick up the guy they will do so. There is no stopping them.”

Hasan said an hour in the hands of the Rangers was more than he could take, and he worries about the Pakistan Protection Ordinance law, which allows authorities to detain a suspect without charge for up to 90 days.

Authorities use the law and other counter-terrorism measures to silence critics, as Hafiz Husnain Raza, who was jailed for nearly two years, found out.

Raza’s case had less to do with the expanding narrative of the military, than its material interests—specifically land. Since at least 1997, farmers in the Okara area of Punjab province have clashed with the military over land the military wants to reclaim. “There were many casualties,” said Farooq Bajwa, Raza’s lawyer in Lahore. “Several tenant farmers were killed, and [other farmers] still didn’t vacate the land. They had one demand: either give us ownership rights or let us stay here as tenants and pay you shares of our crop.”

Since 2010, Raza has covered the protests for Pakistan’s leading conservative-leaning Urdu-language newspaper Nawa-i-Waqt. He took over the job from his late father, a reporter who also spent time in jail for his work.

On April 25, 2016, police arrested Raza and held him incommunicado for 90 days under the Protection Ordinance. During that time, he was mistreated and lost weight, Bajwa said. Getting bail proved elusive. “On at least six occasions, Hafiz Husnain was granted bail and allowed to leave jail if he submitted a surety bond, but each time he had the chance to be released from jail, a new charge was brought against him,” said Bajwa. In total, Raza faced 11 terrorism charges, and six related to weapons.

Raza’s paper tried to intervene but his case faced near total blackout of coverage by other media. “The actions against him by local authorities were a deterrent to other journalists, and so far few journalists have raised their voices for him to be released from prison or for the cases against him to be closed,” said Bajwa, confirming what several journalists told CPJ privately in Lahore: they were afraid because the military was involved.

Bajwa said he received anonymous phone calls offering him money to drop the case. Raza’s family also suffered. “The house was raided, [police] broke the locks and entered our house,” said Raza’s mother, Azhara Parveen. “Inside, they found nothing. But the charges they made against Hafiz—that he had grenades, etc.—they didn’t leave out anything [even though] the whole neighborhood knew that nothing was found in the house.”

Raza’s brother, Hassan, added, “We would get threatening calls, harassment over the phone, we’d be harassed on the street. We didn’t know how we could go on.” Hassan said he lost his job, and another brother faced spurious legal charges connected to a store he ran.

In March, a court dismissed all terrorism charges against Raza, and granted the journalist bail on remaining charges under the Illicit Arms Act. Bajwa said that by June the remaining charges were cleared, and Raza was able to return to work.

Direct pressure from military authorities is the main issue journalists raised, but they said they also fear blasphemy accusations. The charge is punishable by death, fine, or imprisonment in Pakistan. But for many, deadly mob violence following a public accusation is more frightening than a conviction. Since 1995, no one convicted of blasphemy has been executed, but at least 65 murders have resulted from false accusations, according to a 2017 report from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, an independent nonprofit.

Pakistan’s reaction to blasphemy is tied to the country’s identity as an Islamic republic—which was used to try to bring unity after partition—and legislation introduced under Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who ruled from 1978 until his death in a plane crash in 1988.

Being accused of, or even discussing blasphemy can be deadly. In April last year, a mob killed a 23-year-old student named Mashal Khan after a debate on religion. “When [Khan] was killed, we could not say openly that he was innocent,” said Farzana Ali, Peshawar bureau chief for Aaj TV, who covered the story. Co-workers and security personnel at the university where he was attacked warned her that defending the victim would create security risks. In February, a court in Peshawar convicted 31 people in the murder, one of whom was sentenced to death.

Among the press, Geo News executives said the station and staff have come under verbal attack for blasphemy. Noorani showed CPJ photos of posters in Chiniot and other cities in Punjab that accused him of blasphemy. The Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) banned TV commentator Amir Liaquat from hosting or appearing on any program after he repeatedly accused activists and journalists of blasphemy on his show, “Aisay Nahi Chalay Ga” on the BOL network, according to news reports. And, in June last year, a car struck Express Tribune journalist Rana Tanveer in what the journalist said he believes was an attempt to kill him over his coverage of religious minorities. Prior to the attack, threatening messages were daubed on Tanveer’s Lahore home.

With religion, “even discussing politics or serious conflicts can be a red line,” said Dawn editor Zaffar Abbas. “In many of the cases, it’s discussion on laws that have been introduced in this country in the name of religion. Like the blasphemy law, like the Hudood Ordinances [introducing elements of Sharia in 1977], that can be a red line which, if crossed, can bring trouble.” Several editors at major publications said they ask to see all stories related to religion before publication for fear of inadvertently provoking an extreme reaction—an editorial procedure that inevitably induces caution and self-censorship among reporters.

Also hanging over journalists is a fear of abduction. At an Islamabad press conference in January journalist Taha Siddiqui said he barely escaped an attempted abduction. In January the previous year, four activists and bloggers were abducted from Karachi and Lahore, and later released. One of them, Waqass Goraya, told the BBC that he was punched, slapped and forced into stress positions while held by an organization with links to the military. The military denied responsibility.

Pakistan’s government-appointed Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, founded in 2011, has received 4,608 cases, according to Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, with many from the eastern Pakistan provinces of Baluchistan or Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. While few of these directly involve journalists, editors and reporters said they are acutely aware of the cases and fear they could be next.

Pakistan’s press has self-help measures to help deal with these threats. Otherwise fiercely competitive editors in 2015 formed Editors for Safety, essentially a WhatsApp group used to mobilize and coordinate publicity and public pressure when a journalist is abducted or attacked. Safety Hubs, organized by Freedom Network, offers assistance around the country to journalists in trouble. Other organizations, including the Pakistan Press Foundation, provide safety training.

Covering regions experiencing rebellion or ethnic division is also challenging. Tensions in these areas go back to partition in 1947 and ethnic and religious unity remains elusive, as the large and politically dominant population of Punjabis in the east exerts a sometimes uneasy control over other regions.

As part of the 2014 crackdown on militancy, the army became increasingly active in areas including Baluchistan, home of a separatist movement, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with its concentration of ethnic Pashtuns. While the result has been a reduction in militant violence, journalists found themselves caught in the middle.

“Journalists can’t afford to report an independent story,” said a senior journalist who has been based for years in Baluchistan’s provincial capital, Quetta, and who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation by his employer or Pakistan’s intelligence services. The journalist was so spooked that he refused to meet in public.

Baluchistan has long been dangerous for journalists trying to report on the province’s long-running independence insurgency and military’s determination to stamp it out—with both sides willing to act against the press.

A 2011 ruling by the Baluchistan High Court banned coverage of Baluch separatists or nationalist groups, stating that “If the electronic media and the press publish propaganda reports out of fear and propagate the views of banned organizations they are not acting as good and responsible journalists, but as mouthpieces for malicious and vile propaganda.” The court ordered the government to enforce the ruling, which could lead to a six-month jail sentence.

The ruling proved impossible to follow for many journalists, as militant groups threatened them with violence to ensure their statements and actions were reported. “Better we are jailed for six months than to be killed by one group or another,” former president of the Quetta Press Club, Shahzada Zulfiqar, told Freedom Network.

At least 11 cases have been registered against journalists for violating the ban on coverage, according to a November 2017 Freedom Network report.

In October 2017, militants announced a ban on the distribution of newspapers in Baluchistan. They threw a hand grenade at a news distribution office in Turbat, leaving eight injured. Gunmen opened fire on a newspaper delivery vehicle in Awaran, and then burned the newspapers, according to a report in Dawn. The attacks halted newspaper distribution. The militants eventually relented, according to the Quetta correspondent, because they were losing support among businesses affected by the ban.

The situation is not much better in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and its provincial capital, Peshawar, about 350 miles northeast of Quetta. “The situation now is that there is no access to information,” said Ali, the Aaj TV bureau chief. “A press release or some sort of handout comes in, we publish it, we put it on air. We discuss it and analyze it. But the alternative views, the real pictures, that come up on social media, for example, we can’t cover.”

Ali faces an additional set of challenges as a female journalist covering a conflict zone in a religiously conservative part of Pakistan. “There’s this Pashtun mentality that’s already been an obstacle for us: you can go here, you can’t go there, you can do this, can’t do that,” she said.

Ali said that when traveling to cover a rally by the conservative Difa-e-Pakistan, young participants blocked the road and smashed a water bottle on the windshield of her vehicle. When her male colleagues asked what the problem was, they were told, “Send this woman home. Islam doesn’t allow women to roam around like this on the streets.” Ali said that when her colleagues responded that she was a journalist, the group said they didn’t care.

“I was the first woman bureau chief [of a TV channel] in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the second in Pakistan,” Ali said. “In this male-dominated society of ours, women are stereotyped as being too emotional, unintelligent, unable to understand things.” She added, “There is a glass ceiling over us women, especially in this area. If you break through that, come out, and try to do something new, you face dangers. both socially and from your environment, whether from non-state organs or state organs, from political groups, from religious groups.”

Because of the dangers and restrictions in the region, correspondents tend to stay in the cities and report from military or government press releases. “We cannot cover any story except what the military wishes,” the Quetta-based correspondent said.

The correspondent added that the press struggled with how to cover an incident in January when a roadside bomb killed six soldiers. A militant group claimed responsibility but, the correspondent said, most news outlets simply ran the military’s version that described it as a road accident.

Dawn editor Abbas said, “In many parts of Pakistan, both sides have managed to create an atmosphere of fear that is preventing free thinking and honest and objective reporting … That atmosphere of fear has increased over a period of time, and when reports come about abduction or attempted abduction of a free-thinking journalist in Islamabad or Karachi or elsewhere, it solidifies this whole notion that journalists remain under threat.”

Size and market power are also no protection from military pressure to shape news coverage.

By all accounts Geo News had won the ratings battles, burying the competition with an average 7 million cable and satellite viewers—more than four times that of its nearest competitor, according to a 2013 report by the national TV ratings service, Gallup. Its popular 24-hour news programming was sent around the country on cable channels, along with increasingly popular and profitable entertainment and sports channels.

But in April, local cable distributors stopped transmitting Geo’s programming—not just the news, but the entertainment and sports channels as well—without warning.

In a WhatsApp conversation, Azhar Abbas, Geo News managing director, said roughly 80 percent of households were cut off. Even an order from PEMRA, the broadcast regulator, requiring cable companies to restore transmission or face a suspension of their licenses went ignored. Geo was facing an imminent financial crisis. Azhar Abbas said in late May that the situation eased, but he expected the station to remain under pressure in the run-up to the election.

As with Noorani’s case, it’s hard to document who made the order and for what reason.

Geo News’s clashes with authorities started well before April 2018 and exemplify the divide between some media houses and the military, divisions among media groups that once spoke in a single voice, the growing use of indirect tactics to impose censorship, and the rise of self-censorship.

These tensions came to the fore in the aftermath of the attack on Mir in April 2014, when the journalist’s brother blamed the ISI on air. The incident sowed the seeds of distrust and conflict between the press and the military and widening divisions among media groups.

“When Hamid Mir was attacked in Karachi … we saw the division among the media owners in public for the first time,” said Khattak. “Those media houses were split among themselves and they were accusing and blaming each other for being ‘anti-Pakistan,’ ‘Indian agent,’ ‘Jewish lobby,’ ‘American.’ All these labels we heard in public. I think that really hurt press freedom directly. That hurt the unity among the journalists, also. The journalist representative body at the federal level, which is called the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, was split into more than two groups.”

In spite of divisions, the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists came together in July 2018 to protest what it called “pre-censorship” of the media, including blocks on the distribution of Dawn.

As the Mir attack divided the journalists, owners too lost a single voice. “They are split,” said Khattak. “Some are pro-government. Some are pro-establishment. Some are anti-government. Some are anti-establishment, whatever you call them. But we, as a media freedom campaigner and defender, think that is a serious blow to media freedom in Pakistan. It’s extremely difficult to bring all these media owners to a single table around a single point agenda that is the journalist protection or media freedom.”

Ali, of the Pakistan Press Foundation, added, “The media itself has become polarized and does not speak with one voice on issues related to freedom. If you talk to print journalists, they will say electronic television journalists are irresponsible. If you talk to electronic media, they will say online media is really irresponsible. If you talk to one media house they will say the other media house is irresponsible. So, the level of polarization has increased to really unacceptable levels, and everybody’s confused. Is press freedom part of the solution, or is it actually part of the problem?”

Sadaf Khan, co-founder of Media Matters for Democracy, the media research and advocacy group, said, “We see a dip in credibility, there is a trust deficit … So there is a feeling with the media consumers community that the media … cannot be trusted with handling its job with responsibility. They don’t have any public support.”

Meanwhile, “the establishment” has an effective way to put pressure on broadcast media: just tell local TV cable operators to block transmission. “In some areas they completely shut you down,” said Geo TV’s Azhar Abbas. “And other areas they put the channel to a high number, or they keep switching the [channel] numbers.” Changing the channel number makes it hard for viewers to find the station. Abbas said he’s lost track of how many times it’s happened since 2014, when the blockages started. “In the past year, a couple of months back, we negotiated with the military and they started opening up a little,” he said, without providing specifics of the negotiations.

PEMRA did not respond to CPJ’s email request for comment.

A number of editors at newspapers and broadcast media also described a step-up in phone calls from the military advising or complaining about coverage, although they often declined to talk about it openly. The calls are not necessarily threatening. But they all agreed: they were hard to ignore. “We are not airing anything that is against the military as such,” said Azhar Abbas. “It’s the whole narrative that matters. If it’s the sit-in in Islamabad, if we are more critical of one party, they will raise an eyebrow. If we air the speeches of [disqualified former prime minister] Nawaz Sharif too much they will ask why. If we air something that India has offered, they will say that we are giving the Indian point of view.”

Geo TV President Imran Aslam said, “This must be the only case when a TV station is banned because it’s seen as being pro-government.” While Geo, and the Jang media group that owns it, do not see themselves as biased toward the PML-N or former prime minister, Sharif, they gave ample coverage to the government, which was unpopular with the military because of Sharif’s efforts to bring the military under civilian control.

In April, columnists at some newspapers—including Mosharraf Zaidi and Babar Sattar at The News—began complaining on Twitter that their publications had rejected their writing on sensitive topics for the first time, and without explanation. Both these writers put their columns on Twitter.

The News did not respond to CPJ’s email request for comment.

In May, Twitter was alive with reporters complaining about a news blackout of demonstrations in Peshawar, Lahore, and Karachi aimed at securing rights for Pashtuns. Journalists say pressure from the military effectively led to a ban on coverage. “In the newsroom, I could feel developing a self-censorship mode among my senior editors,” said Azhar Abbas. “Anything that’s critical of the army or sensitive. We used to feel, ‘write whatever you want.’ Of course, get the facts right. Now, people are scared.”

A survey published on May 3 by Media Matters for Democracy found that 88 percent of the 156 journalists who responded said they had censored what they write or report. About 72 percent said the trend had increased over time. Seven in 10 journalists said that censoring what they wrote made them feel safer. Six in 10 said they were very likely to self-censor information about the security establishment or religion and around 83 percent said they would likely censor information about militancy and terrorism.

“I think the numbers [of killed journalists] are going down because the resistance from the media that used to come, let’s say five years or six years ago, had drastically gone down as well,” said Asad Baig, founder and executive director of Media Matters for Democracy. “And that is perhaps because of the very organized control mediums in place. People are very clear about what to say, and what not to say, what are those clearly drawn red lines that they cannot cross. And these are not just the journalists, but the media owners, editors and all the way up.”

In other words, Pakistani media consumers aren’t getting a full or accurate picture of critical issues facing the country. This is no accident. The military and other powerful institutions have established lines of control to stifle the press, by promoting people and issues considered favorable, and limiting the dissemination of content found objectionable.