3. Critical journalists silenced by threats of arrest or violence

Harassment of the press from official quarters does not begin or end with the passage of troublesome legislation. Journalists say they are routinely threatened, intimidated, and even attacked, and that government authorities are the culprit more often than not.

According to research by CPJ and the Media Council of Kenya, there were an estimated 19 cases of threats or attacks against the press between January and May 2015, almost one a week, and all but three involved police or other state officials, including members of county assemblies.

What’s more, the attacks take place in a climate of almost total impunity, with few officials ever held to account.

“Journalists have been exposed for a very long time,” said former Nation Media Group editorial director Wangethi Mwangi. “There is hardly any mechanism to give journalists the comfort they need when they are out in the field.”

A 2013 survey by the Kenya Media Programme polled 282 journalists across the country and found that the media is regularly induced to self-censor on crucial issues such as politics, corruption, and land.

More threats against the press are made over the phone than by any other means, according to the survey. “Repeated threats over the phone can really silence a journalist, since you never know when the caller may act on that threat,” said freelance journalist Robert Wanjala, who formerly contributed to the regional independent Mirror Weekly in Eldoret in the Rift Valley in Western Kenya.

Wanjala is familiar with one rare case where death threats directly preceded a journalist’s murder.

John Kituyi was the editor and publisher of the Mirror Weekly; he was killed on April 30, 2015, when unknown assailants on a motorcycle attacked him as he was walking home from work in the evening. They hit Kituyi repeatedly with a blunt object and seized his phone, but did not take his money or his watch, according to news reports and the journalist’s family members and local journalists who spoke to CPJ.

“John received phone threats countless times throughout his career to the point he grew numb to them,” his brother, David Wabwile, told CPJ. “But on April 28 he had confided to me that he was scared and was considering leaving Kenya altogether.”

Two local journalists in Eldoret are still investigating the motive for the murder, but they told CPJ they suspect it is linked to Kituyi’s reporting into the International Criminal Court case against Deputy President William Ruto. The ICC has accused Ruto, whose hometown is Eldoret, of crimes against humanity relating to the ethnic violence following the December 2007 elections, which resulted in more than 1,000 deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Ruto denies the charges. (A similar case against President Kenyatta was withdrawn in late 2014 for lack of evidence; the prosecutor accused the Kenyan government of harassing witnesses.)

A week before his death, the Mirror Weekly published a story headlined “Now ICC plot to jail Ruto,” that described the latest developments in the ICC case against the deputy president. Furthermore, “[Kituyi] was compiling information on an ICC witness who had disappeared and had planned to release the story in the next edition,” Wanjala told CPJ. The next edition was never published.

Asked for comment, a spokesman for Ruto, David Mugonyi, dismissed claims of a connection between Kituyi’s death and his reporting on the ICC case. “I doubt the journalists’ ability to investigate [Kituyi’s] death. This is the province of the police and the journalists cannot purport to claim they know the reason or motive,” he told CPJ. “Mainstream newspapers, which have a huge circulation, publish all manner of stories day in day out on the ICC and the deputy president, they are free to do so. Nothing happens to them.”

Since the ICC process began in 2010, CPJ has helped three journalists relocate from the Rift Valley area because they feared attack for their coverage of the case.

Kituyi’s murder was the first one CPJ has confirmed as directly related to a Kenyan journalist’s work since 2009, when the body of Francis Nyaruri, a reporter for the privately owned Weekly Citizen in Nyanza Province, was found decapitated and bearing marks of torture in a forest. (Another journalist, Bernard Wesonga, died in suspicious circumstances in 2013, but CPJ has been unable to confirm a link with his work.)

Nyaruri had written stories accusing top police officers of fraud in a construction project, according to the Weekly Citizen. Local journalists told CPJ at the time that individuals had threatened him in response to the articles. A CPJ investigation, which included a review of law enforcement documents and interviews with people involved in the case, found evidence that senior officials engaged in a large-scale effort to obstruct the investigation into Nyaruri’s murder. No one has been convicted for the crime, and the case is at a standstill, according to Nyaruri’s widow, Josephine, who has consistently attended court hearings.

Nyaruri’s murder came against the backdrop of what the United Nations in 2009 called “systematic, widespread and carefully planned” extrajudicial killings by police—a topic that can also lead to trouble for investigative journalists.

John-Allan Namu and Mohammed Ali head an award-winning team for the privately owned broadcaster KTN that has covered suspected extrajudicial police killings as well as other sensitive security issues like the response to terror attacks on Westgate Mall in 2013 and in the coastal town of Mpeketoni in 2014. Their pieces, aired in Swahili as “Jecho Pivu” and in English as “The Inside Story,” have routinely resulted in threats—both anonymous death threats via social media or text message and direct confrontations, such as when Kenya’s inspector general of police singled them out at an October 2014 press conference, saying authorities would “come for you, we will deal with you firmly.”

According to Ali, he went into temporary hiding in December 2014, after receiving death threats for his involvement in producing an Al-Jazeera documentary that focused on alleged extrajudicial killings by Kenyan police.

Namu and Ali told CPJ that most of the threats they receive via social media result from their having cast the government in a negative light, and not because the commenters are questioning the facts presented. Nonetheless, KTN eventually took its investigative pieces on terrorism off YouTube in response to pressure from government authorities and from their supporters on social media, Namu claimed. CPJ’s calls and emails to two editors at KTN and the chief executive of the Standard Group, which owns the station, were not answered. Namu said his team has become “more choosy” about which topics it covers.

Such circumspection ultimately leads to Kenyans being deprived of important information about their own country. Security failures were at the heart of an investigation by K24 journalist Purity Mwambia, who attempted a daring feature for a TV segment called “Bweta la Uhalifu” (Signs of Crime). As part of her research, Mwambia said she acquired explosives and transported them from Garissa, in northeast Kenya, to Nairobi (about 228 miles or 336km), passing through more than a dozen police stations and checkpoints without any officer noticing the material, she said.

“My objective was to expose the loopholes in our security system, something that desperately needs attention given all the terrorist attacks Kenya has faced of late,” Mwambia told CPJ. But the day the piece was scheduled to run, April 27, 2015, officials with Kenya’s anti-terror police summoned her to their headquarters, according to a letter of summons reviewed by CPJ. She was questioned for four hours and threatened with arrest on charges of treason if the piece aired, she said. She noted that she was not charged for smuggling explosives. The piece has not been broadcast, and Mwambia went into hiding due to fears that she was being monitored by disgruntled officers, she told CPJ. Mwambia’s colleague, cameraman Francis Mwangi, told CPJ he had similar fears about police surveillance and also went into hiding.

In northern Kenya close to the border with Somalia, journalists trying to cover security are sometimes squeezed between pressure from Al-Shabaab militants and local Kenyan officials vying for control of the news narrative. Investigative journalist Noor Ali, who covers the area, said authorities warned journalists in March to be “patriotic” and to refrain from reporting increased youth recruitment by Al-Shabaab, despite the need for local officials and society to address the problem. Star FM journalist Hussein Salesa said journalists fear the kinds of deadly reprisals witnessed in neighboring Somalia, where dozens of journalists have been murdered. According to CPJ research, the situation conforms to a global trend in which journalists face pressure both from suspected terrorist groups and from authorities whose job is to protect against terrorism.

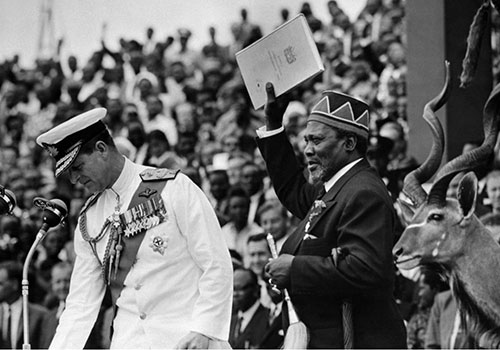

Another sensitive issue with potential to go underreported, journalists say, is land, a hotly contested topic for more than half a century, according to analysts. Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, used land grants as political patronage, writes academic Kathleen Klaus. Injustices in land allocation “have been a recurring factor in outbreaks of violence,” particularly when politicians seek electoral support from the communities involved, according to freelance journalist Wanja Gathu. The violence that erupted after the 2007 elections partly reflected tensions over land access, according to a report by the Kenyan Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission.

Furthermore, investment in land is a lucrative business, with the average price in 2014 more than five times the price seven years earlier, according to the local Hass Property Index. News reports have alleged illegal acquisitions by politicians and powerful business interests. And the Switzerland-based Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre has reported that thousands of people from the coastal region face displacement and forced evictions due to land grabs.

“If the media refrains from addressing land issues,” photojournalist and activist Boniface Mwangi said, “then land grabbing and corruption by individuals in government and others will continue as they have done since independence, at the expense of [the] populace.” But if the media refrains, it is perhaps for good reason.

On March 22, three unknown assailants bundled into a car Standard reporter Michael Olinga as he was walking home from watching a soccer match, he told CPJ. In the car, the kidnappers, two men and one woman, questioned his reporting on land allegedly stolen from a public school in Uasin Gishu County, in western Kenya. Olinga believes he was drugged because he later awoke lying on the floor of an empty room. “They kept me from Sunday until Tuesday morning. I have no idea what happened on Monday,” he said. “I have avoided covering land stories since then.” The assailants took Olinga’s phone and wallet, but he is convinced the attack was an act of intimidation to keep him silent, not a robbery.

In May, an opposition party chairman accused of land-grabbing in the western town of Gilgil was captured on camera firing a gun at journalists who attempted to report on the matter, according to news reports. A court charged the politician with attempted murder and incitement of violence in late May.

However, journalists say that action against perpetrators of anti-press violence is not the norm, and many consider reporting them to be a futile exercise. In 38 percent of cases, the KMP survey found, journalists do not report the threats they have faced.

To date, no action has been taken against the paramilitary police who beat journalists Nehemiah Okwembah and Reuben Ogachi when they tried to cover the corruption case involving cattle in Tana River County, even though they filed a police statement and the attack was caught on camera.

Instead, Okwembah said, he believes individuals have since been following him. “I think that some forces are working hard to stop us from pursuing justice in court,” he told CPJ. “So now I stay at home and take taxis when needed; I do not want to appear in public.”

For some journalists, particularly those outside of Nairobi who operate under informal employment arrangements, the problem of harassment and attacks is exacerbated by the negligible support received from media houses.

Janak, chairman of the Kenya Correspondents Association, said the lack of infrastructural or financial support for correspondents, who are essentially treated as freelancers, makes them particularly vulnerable to threats and bribes. “Despite producing 70 percent of the daily news content, Kenyan correspondents working for media houses receive no contracts, no benefits,” he told CPJ.

“They are hired by phone and fired by phone,” said Kenya Union of Journalists Secretary-General Erick Oduor, and are paid only when their stories are used. Therefore, when officials offer to pay correspondents’ travel costs or provide transportation to press conferences, the journalists typically accept, compromising their ability to report critically about the officials, he said.

According to photojournalist Mwangi, politicians in some cases are co-opting journalists, editors, and media owners at both the national and county level. StandardGroup’s digital content editor Ohito said the paying of journalists by officials has created animosity and distrust within the press corps, pitting those who support the government against those who remain independent and critical.

“Many county governments have communications divisions that pay certain journalists monthly ‘compensation,’” said veteran journalist and former chief editor of the Star Catherine Gicheru. She added that while government officials deny the existence of any such arrangements, the results can be seen in the superficial nature of some reports.

In one example of a close relationship between journalists and authorities—albeit one that may not have protected the journalist from official intimidation—in September 2014, Siaya County Governor Cornel Rasanga physically assaulted Star reporter Eric Oloo and Radio Mayienga reporter Javan Onyango after the two covered a dispute between local officials, according to the KUJ. In denying the allegations, Rasanga claimed that Oloo was actually employed by the county, according to news reports. Oloo confirmed to CPJ that he had worked for the county but on a temporary basis and had finished the work contract prior to the attack.

There is no longer solidarity among journalists in defending press freedom, Gicheru told CPJ. “Before we look at fences built around us [by government], we need to see the fences that we are building between ourselves,” she said.