The May 11, 2022, killing of Al-Jazeera Arabic correspondent Shireen Abu Akleh is part of a deadly, decades-long pattern. Over 22 years, CPJ has documented at least 20 journalist killings by members of the Israel Defense Forces. Despite numerous IDF probes, no one has ever been charged or held responsible for these deaths. The impunity in these cases has severely undermined the freedom of the press, leaving the rights of journalists in precarity. A CPJ special report.

Published May 9, 2023

In this report

Introduction

Interactive map

Main findings:

–Israel discounts evidence and witness claims

–Israeli forces have failed to respect press insignia

–Israeli officials respond by pushing false narratives

–Journalists are accused of terrorism

–Israel opens probes amid international pressure

–Officials appear to clear soldiers while probes are ongoing

–Inquiries are slow and not transparent

–IDF killings undermine independent reporting

–Families of journalists have little recourse inside Israel

Sidebar: A deadly reporting field for Palestinian journalists

Sidebar: How Israel probes journalist killings

Faces of killed journalists

Credits: Orly Halpern, reporter and analyst; Naomi Zeveloff and Robert Mahoney, editors (full credits here)

Recommendations

Read the report in Hebrew and Arabic:

Introduction

On May 11, 2022, Palestinian American television journalist Shireen Abu Akleh embarked on what would be her final assignment. At 6:31 a.m., she walked down a neighborhood road in the Israeli-occupied West Bank city of Jenin. She was accompanied by two other Palestinian journalists and her producer, Ali al-Samoudi. The group wore protective vests with the word “Press” in large white letters across their chests and backs. Ahead they could see several Israeli military vehicles.

The journalists were there to report on the aftermath of an Israeli raid in the Jenin refugee camp after a string of deadly attacks by Palestinians in Israel. Video recorded by TikTok users and republished by The Washington Post showed Abu Akleh, a veteran Al-Jazeera Arabic correspondent, and her colleagues on the street. In the minutes before, the area was relatively quiet as local residents milled about, save for the sound of gunfire in the distance.

Suddenly, six shots rang out, one of them hitting al-Samoudi in the shoulder. The journalists ducked for cover and there was a second volley of fire. A bullet hit Abu Akleh in the back of her head in the gap between her helmet and her protective vest, killing her instantly. Several independent investigations by U.S. news outlets, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Associated Press, as well as Netherlands-based research collective Bellingcat, all came to the same conclusion: a member of the Israel Defense Forces likely fired the shot. CNN found evidence of a targeted attack. The London-based research group Forensic Architecture and the Ramallah-based human rights organization Al-Haq also found evidence that the Israeli army targeted Abu Akleh and her journalist colleagues with the intention to kill.

Five months after the killing, an IDF probe concluded there was a “high possibility” that one of its soldiers “accidentally” shot the journalist while firing on Palestinian gunmen, but did not rule out the possibility that she was shot by a Palestinian militant. To date, no one has been held accountable.

The killing of Abu Akleh, one of the Arab world’s most beloved and recognizable journalists, was not an isolated event. Since 2001, CPJ has documented at least 20 journalist killings by the IDF. The vast majority — 18 — were Palestinian; two were European foreign correspondents; there were no Israelis. No one has ever been charged or held accountable for these deaths.

Interactive map

Profile name

Ahead of the first anniversary of Abu Akleh’s death, CPJ revisited these 20 cases and found a pattern of Israeli response that appears designed to evade responsibility. Israel has failed to fully investigate these killings, launching deeper probes only when the victim is foreign or has a high-profile employer. Even then, inquiries drag on for months or years and end with the exoneration of those who opened fire. The military consistently says its troops feared for their safety or came under attack and declines to revisit its rules of engagement. In at least 13 cases, witness testimonies and independent reports were discounted. Conflicts of interest in the chain of command are overlooked. The military’s probes are classified and the army makes no evidence for its conclusions public. In some cases, Israel labels journalists as terrorists, or appears not to have looked into journalist killings at all. The result is always the same — no one is held responsible.

Israel’s efforts to examine its soldiers’ actions, particularly when it comes to Palestinian journalists killed, amount to less of a serious inquiry than a “theater of investigation,” said Hagai El-Ad, the executive director of Israeli human rights group B’Tselem.

“They want to make it look credible. They go through the motions, things take a lot of time, a lot of paperwork, a lot of back and forth,” he told CPJ. “But the bottom line after all this maneuvering is almost blanket impunity for security forces when using lethal force against Palestinians that is not justified.”

Israel’s army is responsible for 80% of journalist and media worker killings in the Palestinian territories in CPJ’s database. The other 20% — five cases — died due to different causes. Two Palestinians were shot by gunmen in Palestinian Presidential Guard uniforms in 2007; one Palestinian was killed in what was likely an accidental explosion at a Palestinian National Authority security post in 2000. And in 2014, an Italian foreign correspondent and his Palestinian translator died on assignment while following a team of Palestinian engineers neutralizing unexploded Israeli missiles when one detonated.

CPJ’s research spans some of the most violent and repressive years of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, from the start of the Palestinian uprising known as the Second Intifada, in 2000, to repeated Israeli operations against militants. All deaths took place in the West Bank, territory under Israeli military occupation, or in Gaza, a coastal strip under Israeli military blockade. No journalist was killed within Israel’s internationally recognized borders.

Deaths are just one part of the story. Many journalists have been injured, and in 2021 the military bombed Gaza buildings that housed offices of more than a dozen local and international media outlets, including The Associated Press and Al-Jazeera.

Journalists are civilians under international law, and as such militaries must take steps to safeguard them during hostilities. Yet while international law forbids the targeting of civilians, it also acknowledges that such deaths cannot be fully avoided, and doesn’t require armies to investigate themselves every time they occur. Indeed, Israel never announced probes into at least five — a full quarter — of the IDF killings in CPJ’s database. “That doesn’t mean there aren’t situations when investigations are appropriate and necessary to see if someone made an unreasonable judgment related to the use of force,” said Geoffrey Corn, a military law expert at Texas Tech University and a fellow at the pro-Israel nonprofit Jewish Institute for National Security of America.

Israel’s army is responsible for 80% of journalist and media worker killings in the Palestinian territories in CPJ’s database.

Israel’s current military investigative system was born out of the 2010 Turkel Commission, a government commission established in part to ensure Israel was investigating its military actions in accordance with international law. The commission was set up amid concerns that Israeli officials could be arrested abroad for alleged war crimes. In order to avoid the International Criminal Court, which, under the ICC’s principle of complementarity, can exercise jurisdiction where national legal systems are unable or unwilling to act, Israel needed to bolster its institutions to prove it could handle such allegations at home.

Since 2014, the military has opened “fact-finding assessments” into “exceptional incidents” in which the army needs more information to determine “whether there exists reasonable grounds for suspicion of a violation of the law which would justify a criminal investigation,” according to the IDF. Once the assessment is complete, it is delivered to the Military Advocate General, who decides whether to pursue a criminal track in the case. The Israeli military has opened fact-finding assessments into the killings of five journalists, including Abu Akleh, since 2014. It also opened a fact-finding assessment into a large-scale bombardment which killed three other journalists during Israel’s 2014 Operation Protective Edge in Gaza. (Prior to 2014 it opened preliminary probes or conducted very basic checks into other journalist deaths.)

Human rights groups, and Israel’s own state comptroller, have raised concerns about the independence and slow pace of these totally confidential assessments, which can drag on for months or years, by which time witnesses’ memories fade, evidence may disappear or be destroyed, and soldiers involved can coordinate testimonies. In the nine years that this assessment system has been in place, the Military Advocate General has never opened a criminal probe into a journalist killing. (Israel did open one military criminal investigation into the 2003 killing of British journalist James Miller, but closed it without putting the soldier on trial.) Israel has rebuffed claims that its investigative systems are flawed; the IDF says Israel is a “democratic country committed to the rule of law.”

Investigations into military activity are controversial in Israel, where conscription is mandatory and soldiers are broadly seen as the nation’s sons and daughters. In 2017, when Israeli soldier Elor Azaria stood trial for the extrajudicial killing of an incapacitated Palestinian assailant, mass protests erupted. Azaria’s charge was downgraded from murder to manslaughter and he was released nine months into his reduced 14-month sentence.

Shlomo Zipori, a former chief defense attorney of the Military Advocate General’s unit, who represents soldiers in criminal cases, told CPJ that investigations must be weighed against military objectives, as soldiers may begin to overthink their moves in the field if they fear being tried. “I represented a soldier who was still serving in the army while under criminal investigation for killing a Palestinian and injuring another,” he said. “Someone threw a Molotov cocktail at him and he didn’t respond because he was so traumatized by the interrogations he went through in the hands of the military police and he didn’t want to go through them again.” Zipori is also concerned for soldiers’ futures. “If you convict him, you’ll ruin his life,” he said. “There are more than 50 professions he can’t do in civilian life for 17 years if he’s convicted.”

Corn told CPJ that launching a criminal investigation into every killing, even when evidence of criminality is “murky” or insufficient, could impact soldiers’ abilities to do their jobs in the field. Soldiers will assume that every civilian injury will subject them to investigation. “Conversely, when the evidence credibly suggests a violation of law or policy and you don’t do anything about it, you are incentivizing other people to break the rules,” he said.

Time and again after a journalist killing, Israel affirms its commitment to the rights of journalists. “The IDF sees great importance in preserving the freedom of the press and the professional work of journalists,” the army said in an emailed statement to CPJ.

Israeli officials often repeat the assertion that Israel “does not target journalists.” But Israeli authorities need not prove that a killing was intentional in order to open a criminal case into the conduct of a soldier or the soldier’s superiors. There are many other lesser crimes in the country’s military law that could apply, including the Israeli equivalent of involuntary manslaughter. Israel has never put a soldier on trial for an intentional or unintentional killing of a journalist.

“The state has obligations that it might or might not be following, but I think also a democracy can demand more than the legal minimum,” said Claire Simmons, co-author of recent guidelines for states on investigating violations of international law published by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Geneva Academy. Citizens in democracies can send a strong message to their governments, she said: “‘We are demanding that you be accountable to the actions that you are being involved in, and that you do a better job of protecting lives in armed conflict.’”

So far, the lack of accountability has created a more dangerous reporting environment for local and foreign reporters alike. “Many reporters covering similar raids and tensions — which have risen markedly since Shireen’s killing — are afraid of being shot,” said Guillaume Lavallée, chairman of the Foreign Press Association in Israel, in a statement to CPJ. “If a reporter with an American passport can be killed without legal consequence, journalists fear a similar fate could easily await them in the future. That feeling of vulnerability is particularly strong among our Palestinian colleagues. Some of them fear that they might even be targeted.”

CPJ sent multiple requests to the IDF’s press office to interview military prosecutors and officials but the military refused to meet with CPJ for an on-the-record interview. Below are CPJ’s key findings about IDF killings of journalists:

Israel discounts evidence and witness claims

Abu Akleh’s story is a case study in how Israel often discounts evidence reported in the news and elsewhere. Early on in its probe, the IDF released initial findings raising the possibility that a soldier may have killed the journalist when responding to Palestinian gunfire. But news organizations quickly poked holes in this narrative.

The New York Times said it reviewed evidence that “contradicted Israeli claims that, if a soldier had mistakenly killed her, it was because he had been shooting at a Palestinian gunman.” The Associated Press noted that the “only confirmed presence of Palestinian militants was on the other side of the [Israeli military] convoy, some 300 meters… away, mostly separated from Abu Akleh by buildings and walls. Israel says at least one militant was between the convoy and the journalists, but it has not provided any evidence or indicated the shooter’s location.” Additional investigations by The Washington Post, CNN, and research collective Bellingcat showed a lack of militant activity in the area at the time of the shooting.

Israel has never put a soldier on trial for an intentional or unintentional killing of a journalist.

These investigations were all published months before the IDF issued its final statement. And while the army claimed that it reviewed “materials from foreign media organizations,” it appeared to totally discount those findings. According to the military, there was a “high possibility” Abu Akleh was “accidentally hit by IDF gunfire fired toward suspects identified as armed Palestinian gunmen during an exchange of fire in which life-threatening, widespread and indiscriminate shots were fired toward IDF soldiers.” The IDF did not rule out the possibility that she was killed by a Palestinian gunman.

The IDF also said that “at no point was Ms. Shireen Abu Akleh identified and at no point was there any intentional gunfire carried out by IDF soldiers in a manner intended to harm the journalist.” But weeks after the final IDF statement, Forensic Architecture and Palestinian human rights organization Al-Haq published a joint report reconstructing the circumstances of the killing.

“According to both the digital and optical reconstructions of the shooter’s vision, the journalists’ press vests would have been clearly visible throughout the incident,” Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq found. The IDF never responded publicly to the groups’ report, which claimed that the military targeted the journalist.

The Foreign Press Association in Israel also questioned why a soldier with what the IDF said was limited visibility fired toward clearly identifiable journalists without firing a warning shot. “If this is normal operating procedure, how can the army fulfill its stated pledge to protect journalists and respect freedom of the press?” The association demanded Israel to publish the full findings of its probe, which it never did.

Israel has discounted evidence in other high profile cases. In 2002, Italian photojournalist Raffaele Ciriello, who was on assignment for Corriere della Sera, stepped out of a building in Ramallah to take a photograph of a tank some 200 yards away and was shot six times. “The barrage undoubtedly came from the road, where there was not a soul, apart from the Israeli tank,” said another journalist at the scene, Amedeo Ricucci, in an article for Italian newspaper Vita. An Israeli Government Press Office official told the Boston Globe, “From that distance, I’m sure it looked like the guy was getting into a firing position and was about to shoot.” However, the IDF’s official position was that it didn’t kill the journalist. The IDF later said that there was “no evidence and no knowledge of an [army] force that fired in the direction of the photographer.”

“The IDF sees great importance in preserving the freedom of the press and the professional work of journalists.”

– IDF statement to CPJ

In 2003, when Associated Press Television News (APTN) journalist Nazih Darwazeh was killed filming clashes between Palestinian youths and Israeli troops, The Associated Press commissioned an independent investigation that “concluded that the fatal bullet could only have come from the position where the Israeli soldier was standing,” according to AP Vice President John Daniszewski.

Daniszewski told CPJ in an email that Nigel Baker, then the content director of APTN, flew to Israel and presented the investigation to an Israeli officer, who suggested that the IDF conduct its own probe, but “AP never heard results of such an investigation or whether one was undertaken at all.”

A 2003 Reporters Without Borders report found the IDF did make some cursory attempts at looking into the killing, but that other journalists at the scene were only interviewed “informally.” One was summoned to meet with an army official seemingly in order to calm tensions.

“AP was and is outraged by this shooting,” Daniszewski said.

Israeli forces have failed to respect press insignia

Like Abu Akleh, the majority of the 20 journalists killed — at least 13 — were clearly identified as members of the media or were inside vehicles with press insignia at the time of their deaths. (All but one of the 20 journalists, who was home when his apartment was bombed, was killed on assignment.) But not only did journalists’ efforts to identify themselves fail to protect them, at times officials have cast suspicion on journalists because of their apparel.

“Many reporters covering similar raids and tensions — which have risen markedly since Shireen’s killing — are afraid of being shot.”

– Guillaume Lavallée, chairman of the Foreign Press Association in Israel

In April 2008, Reuters camera operator Fadel Shana, for example, was wearing blue body armor marked “PRESS” and was standing next to a vehicle with the words “TV” and “PRESS” when a tank fired a dart-scattering shell above his head. His chest and legs were pierced in multiple places, killing him. “The markings on Fadel Shana’s vehicle showed clearly and unambiguously that he was a professional journalist doing his duty,” said then-Reuters editor-in-chief David Schlesinger, who demanded an Israeli inquiry into the killing.

But Avichai Mandelblit, who was then Military Advocate General, had a different interpretation of Shana’s press insignia. He wrote to Reuters four months later that Shana’s body armor was “common to Palestinian terrorists” and that he had placed a threatening “black object” — a camera — on a tripod. These were two of the several reasons he told Reuters that the soldier’s decision to open fire on Shana was “sound.”

Shana’s brother, Mohammed Shana, told CPJ that he never received any answers, or any sort of apology, from the Israeli military. “They shot him because they didn’t want him to cover what was happening in that area.” A Reuters spokesperson told CPJ that the company remains “deeply saddened by the loss of our colleague Fadel Shana.”

Ten years after Shana’s death, in April 2018, then-Israeli Defense Minister Avigdor Liberman was even more explicit with his attempted justification for an IDF sniper’s shooting of Gaza filmmaker Yaser Murtaja, who wore a helmet and a vest marked “PRESS.” “We have seen dozens of cases of Hamas activists [who] were disguised as medics and journalists,” said Liberman, referring to calls for investigation as a “march of folly,” according to The Jerusalem Post.

Murtaja was covering the Great March of Return, a monthslong protest in which Palestinian demonstrators — some of whom hurled Molotov cocktails, rocks, and burning tires at Israeli troops — demanded to return to their historic homelands inside Israel and the lifting of Israel’s blockade of Gaza. Israeli soldiers killed hundreds of Palestinians, including Murtaja and photojournalist Ahmed Abu Hussein, also in a press vest. Dozens of journalists were injured, leading a 2019 U.N. inquiry to find “reasonable grounds to believe that Israeli snipers shot journalists intentionally.”

“It was very obvious we were being targeted,” said Yasser Qudih, a freelance photojournalist in Gaza, who suffered life-threatening injuries after an Israeli sniper shot him in the abdomen while he was covering the Great March of Return in a press vest. Qudih believes his fellow reporters were diligent about wearing press apparel — and that this may have undermined their safety. “There was a large number of journalists and the Israeli government and Israeli army were trying to keep them away,” he said. “The Israeli army was directly targeting the journalists’ locations.”

Israeli officials respond by pushing false narratives

Immediately after a journalist is killed by security forces, Israeli officials often push out a counternarrative to media reporting. In Abu Akleh’s case, officials began to blame the other side even as news reports cited witnesses and the Palestinian health ministry saying she was killed by Israeli troops. “Palestinian terrorists, firing indiscriminately, are likely to have hit” Abu Akleh, the Israeli Foreign Ministry tweeted hours after her killing, along with a video of militants that Israeli human rights group B’Tselem found was taken improbably far from the scene of Abu Akleh’s death. Israeli military spokesperson Ran Kochav told Israel’s Army Radio that Abu Akleh “likely” died by Palestinian fire. He seemed to implicate the journalists in the violence: “They’re armed with cameras, if you’ll permit me to say so,” he said on the radio, before adding that the journalists were “just doing their work.”

By the evening, Israeli officials began to walk back these statements, with then-Defense Minister Benny Gantz promising that Israel would transparently investigate her death. Yet the body tasked with the preliminary probe was overseen by Meni Liberty, a member of the chain of command of the unit operating in Jenin that day. Liberty commands the IDF’s Oz Brigade, which includes the elite Duvdevan unit. The Israeli army identified that unit, known for its undercover work in the Palestinian territories, as a possible source of the fire that killed Abu Akleh, according to Haaretz.

“They don’t consider Palestinian journalists as journalists, they consider us the same as Palestinian demonstrators and they target us like they do demonstrators,”

– Hafez Abu Sabra, a Palestinian reporter with Jordan’s Roya TV

In the case of Murtaja, the photographer killed by Israeli fire in 2018, one Israeli official spent weeks trying to discredit the journalist. Then-Defense Minister Liberman called Murtaja “a member of the military arm of Hamas who holds a rank parallel to that of captain, who was active in Hamas for many years” — a claim repeated on Twitter by two spokespeople for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. But Liberman never provided evidence and The Washington Post revealed that Murtaja had been vetted by the U.S. government to receive a U.S. Agency for International Development grant to support his production company, Ain Media. Liberman also claimed that Murtaja had used a drone over Israeli soldiers when a video showed him with a handheld camera stabilizer. (The Israeli army told Raf Sanchez, then a reporter for British newspaper The Daily Telegraph, that it had no knowledge of Murtaja working for Hamas.)

Journalists are accused of terrorism

Murtaja isn’t the only journalist whom Israel accused of militant activity. In one notable case, the army killed journalists affiliated with a Hamas-run outlet, but never explained why it considered them legitimate military targets. The IDF said Hussam Salama and Mahmoud al-Kumi, camera operators for Al-Aqsa TV, were “Hamas operatives” but a Human Rights Watch investigation found no proof that the two were militants, noting that Hamas did not publish their names in its list of fighters killed. After CPJ called for evidence to justify the attack, the spokesperson for the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., responded two months later with a letter accusing Al-Aqsa TV of “glorifying death and advocating violence and murder.” The letter did not say why the two did not deserve the civilian protections afforded to journalists regardless of their perspective.

In another case, the IDF said that Hamid Shihab, a driver for the Gaza-based press agency Media 24, was transporting weapons in a car marked “TV” when he was killed in an IDF air strike in 2014. The IDF again provided no evidence, saying that “in light of the military use made of the vehicle for the purposes of transporting weaponry, the marking of the vehicle did not alter the lawfulness of the strike.”

Shihab’s brother, Ahmed Shihab, told CPJ this year that the journalist had “no relationship to any Palestinian parties.” He said that the journalist was taking time off to prepare for his wedding when Media 24 called him to pitch in with coverage of Israel’s Operation Protective Edge. After three days of work, he visited his parents for just an hour during Ramadan; after he left the house, he drove to a colleague’s home and was killed.

In yet another case, in 2004, the military told CPJ that Mohamed Abu Halima, who was a student journalist for a radio station at Nablus’ An-Najah National University, had opened fire on Israeli forces, leading them to return fire. But Abu Halima’s producer said that he was on the phone with the journalist moments before he was shot and that Abu Halima had been simply describing the scene around him.

Israel opens probes amid international pressure

The degree to which Israel investigates, or claims to investigate, journalist killings appears to be related to external pressure. Journalists with foreign passports — like Abu Akleh, who had U.S. citizenship — received a high degree of international attention before the army began probes. Israeli officials appear less likely to investigate the killings of local Palestinian journalists, save for those with strong international connections. But there’s a limit to what international pressure can achieve.

In the case of British journalist James Miller, Israel faced the threat of a British request for the extradition of its soldiers and strained diplomatic tension with the British government. In 2003, Miller was shot in the neck by a soldier inside an armored personnel carrier in the Gaza Strip, but in 2005 the army absolved its troops. After a British inquest jury found in 2006 that Miller had been murdered, then-British Attorney General Peter Goldsmith wrote Israeli officials a letter, giving them a deadline to initiate legal proceedings against the soldiers involved, or they would be tried for war crimes in England, Haaretz reported. In 2009, Israel paid approximately 1.5 million pounds (US$2.2 million) in compensation to Miller’s family. After the Israeli payment, the British Ministry of Justice said it would not pursue legal claims or extradition, according to Haaretz.

The Israeli military, which never admitted responsibility in Miller’s death, initially claimed that its troops returned fire after being fired upon with rocket-propelled grenades. In video of the incident, a shot is fired, after which a member of Miller’s crew shouts, “We are British journalists.” A second shot is fired, and appears to hit Miller. The case was investigated by the Israeli military police, but then-Military Advocate General Mandelblit closed it after deciding there wasn’t enough evidence to try the soldier. (The soldier was also acquitted of improper use of weapons in a separate disciplinary hearing.)

The army said the investigation was “unprecedented in scope” and included ballistics tests, analysis of satellite photographs, and polygraph tests for those involved. However, an internal Israeli army report leaked to The Observer revealed that evidence was tampered with, army surveillance video tapes that may have filmed the killing had disappeared, and that soldiers were overheard “lying.” The report said officers assumed soldiers told the truth, and then explained away inconsistencies in their testimonies because “they were confused because of the fighting.”

“This investigation was an unbelievable fuckup and everywhere we looked it was a whitewash by the army,” Michael Sfard, a lawyer for the Miller family in Israel, told CPJ. “There was no intention whatsoever to get to the bottom of what happened there. And only because the victim had British nationality and strong journalistic entities behind him, the Ministry of Defense went as far as to meet with us, to talk with us, to negotiate with us.”

Officials appear to clear soldiers while probes are ongoing

Israeli officials, including those tasked with investigating killings, often make public statements exonerating soldiers before probes are complete. In Abu Akleh’s case, Yair Lapid, a former journalist who was then Israeli foreign minister, went on a press offensive, writing in The Wall Street Journal that accusations that Israel had targeted the journalist were “Palestinian propaganda.” His op-ed ran nearly three months before the IDF released a statement concluding no “suspicion of a criminal offense.”

Similarly, three months before the army completed its probe into the killing of Reuters’ Shana in 2008, an IDF spokesperson said soldiers “acted according to their orders.” “We can say for sure that the soldiers weren’t able to detect that it was a member of the press. The IDF has no intention of targeting press people,” the spokesperson said. Then-Military Advocate General Mandelblit later determined the killing was “sound” in part because of unrelated threats facing soldiers that day.

According to El-Ad of B’Tselem, a soldier’s professed fears can be enough to sway military examiners. “Generally speaking, many soldiers realize that all they need to say is that they felt threatened and so they opened fire,” he told CPJ. “And when a soldier says that then it’s almost guaranteed to be the end of the story, case closed.”

In at least one case, Israeli officials launched a probe with the explicit goal of exoneration. The IDF’s probe into several 2018 Gaza deaths, including Murtaja’s, would “work to back the troops,” an unnamed IDF officer told Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth. “IDF officials stressed that the panel was formed to help IDF soldiers avoid prosecution in the International Criminal Court at The Hague and should not be interpreted to mean that their actions were in some way unwarranted,” the newspaper said.

Inquiries are slow and not transparent

The Israeli military often takes months or years to investigate killings and is slow to respond to groups that petition for answers. The Gaza-based Palestinian Centre for Human Rights asked the Israeli military to investigate Murtaja’s death six days after he was killed, according to Iyad Alami, head of PCHR’s legal unit. In an email to CPJ, Alami said the army asked the group for medical reports and eyewitness statements, which the group provided. Nearly two years later, the army responded asking for the names of witnesses who were prepared to testify. PCHR facilitated those testimonies and responded to other requests, but its efforts then ran aground. In October 2021 it asked the army for the results of its probe. It never heard back.

Another Gaza-based organization, Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, filed a request for the army to investigate photographer Abu Hussein’s killing the day after he died from a gunshot wound, two weeks after an Israeli soldier shot him in April 2018. Mervat Al Nahal, the director of the group’s legal aid unit, told CPJ that the military confirmed it received the request but never asked to interview witnesses. Two years later, the Israeli army informed the organization that it closed the case because there was no criminal intent by the soldiers, Al Nahal said.

When CPJ asked the IDF for the results of its probes into the deaths of Abu Hussein and Murtaja — which occurred within weeks of each other — it received identically worded answers that the journalists were “allegedly present at the scene of violent riots” and “no suspicion was found which would justify the opening of a criminal investigation.”

CPJ asked the IDF for the full probes into the deaths of Abu Hussein and Murtaja and other journalists on CPJ’s list, but the IDF did not provide them. Nor did it answer CPJ’s question about why the army keeps these probes confidential.

In some cases, families never learn what happened beyond what is reported in the press. Abu Hussein’s mother, Raja Abu Hussein, said the Israeli army never contacted her about its probe. “The typical answer the Israeli army gives when it kills civilians is that the army did nothing wrong,” she said, adding that she doesn’t trust the army to investigate itself.

“I wish I could meet the guy who killed my son,” she told CPJ. “I would ask him, ‘Why, why did you target my son?’ I think he won’t have an answer. He is a sniper, he kills.”

IDF killings undermine independent reporting

The IDF killings of journalists have heightened safety concerns for Palestinian and foreign journalists. Gaza journalist Qudih said that Murtaja’s 2018 killing “created fear in the heart of us all,” as journalists’ families begged them to stop their reporting on the Great March of Return protests because of widespread sniper fire.

Those concerns escalated after Abu Akleh’s killing. “I’m not a person who is scared, but I have a 5-year-old daughter who has been telling me she doesn’t want me to go to work so that I won’t be killed like Shireen was in Jenin,” said Hafez Abu Sabra, a Palestinian reporter for Jordan’s Roya TV. “Everyone is scared now especially after what happened to Shireen. Before, they were shooting stun grenades and rubber bullets at us. But now, it’s live bullets and you can lose your life,” he said.

“This is really affecting our coverage,” said Abu Sabra. “We try to avoid places where there are clashes. We try to stay close to ambulances and hospitals and be away from the demonstrators. So, we are much farther away from the event. People are using footage taken by locals in the area and discovering the news in that way.”

Abu Akleh’s killing has also changed the calculus for some foreign news organizations working with local journalists. “Especially after what occurred with Shireen we have taken a much more cautious approach,” said a security adviser for an international news outlet. “If we are dealing with a local national who is doing the primary reporting, if we know of any operations happening in the area we just don’t take chances with these things anymore.” The adviser declined to be named out of concern that the outlet’s journalists would be denied entry to Israel and the Palestinian territories in the future.

The adviser said that in recent years, his news organization has recategorized Israel and the Palestinian territories from a “moderate risk” location to a “high risk” location due to harassment by security forces as well as by settlers and other ultranationalist Israelis that yielded a “very muted response from authorities.” Crews on the ground must now follow stricter communication and safety protocols. They also avoid travel between Israeli and Palestinian areas at night in part out of fears that Palestinians may mistake them for settlers and attack them.

The security adviser pointed to recent access issues. Palestinian journalists have been stopped at West Bank checkpoints and told they cannot proceed to the site of military operations “for your own protection.” Nidal Shtayyeh, a Palestinian photographer for the Chinese news agency Xinhua who was previously shot in the eye while reporting, said these restrictions intensified after Abu Akleh’s killing. “So, there’s no freedom of coverage.” The lack of independent reporting works in the government’s favor, said the security adviser. “They are the only one with a narrative to say ‘this is what happened on the ground.’”

When Shtayyeh did manage to cover a military operation in Jenin in October of last year, he told CPJ that he and a colleague came under fire by Israeli forces while they were filming from inside a building under construction. “We were stuck to the wall for half an hour, terrified that we would be shot,” he said. Their calls for help were broadcast on Palestinian media, where Amira Hass, a veteran Israeli correspondent for Haaretz, heard them. She told CPJ she called the army spokesperson’s office and told a soldier on duty, “Act quickly, because we don’t want another Shireen Abu Akleh, do we?” Soon after, the journalists, who were not injured, were allowed to leave the area.

The IDF Spokesperson’s Unit and the police told Haaretz of this incident that it was “not aware of any accusations of fire being aimed at members of the media.”

Families of journalists have little recourse inside Israel

The family of one Palestinian journalist on CPJ’s list filed a lawsuit in an Israeli court over the journalist’s death, but the case yielded no results. Imad Abu Zahra, a Palestinian freelance photographer who worked as a fixer for the foreign press, was photographing an Israeli armored personnel carrier that had hit an electrical pole in the West Bank city of Jenin when Israeli tanks opened fire, killing him and injuring a colleague in 2002.

“My son used to tell me that as a journalist he was protected and no one would hurt him,” his mother Hiyam Abu Zahra told CPJ. “But he lost his life with his camera, not using a weapon, because he wanted to show the people what was really happening.”

Abu Zahra’s family filed a tort claim in a Tel Aviv magistrate court against the state of Israel for compensation for the death. According to court documents, Abu Zahra’s colleague testified that Palestinians threw fruits and vegetables at the Israeli soldiers before they fired on the journalist. But the judge accepted the state’s version of events and said that the soldiers were forced to “open fire in view of the danger posed to their lives and safety” after a crowd allegedly hurled stones, Molotov cocktails, and used small firearms against them. The judge rejected the family’s claim and in 2011 ordered the family to pay 20,000 shekels (about US$5,800 at the time) in court fees.

Sameh Darwazeh, the son of Associated Press Television News’ Darwazeh, who was killed in 2003, said his family attempted lawsuits in the Israeli system, but eventually gave up because the cost was prohibitive. He said the lack of justice has “opened the way for the repetitive killing of journalists, and the biggest example is the killing of the journalist Shireen Abu Akleh.”

Abu Akleh’s media outlet is looking beyond the Israeli justice system. The Qatari-funded Al-Jazeera Media Network submitted a formal request to the International Criminal Court — which in 2015 said it had jurisdiction over the Palestinian territories — late last year asking it to investigate Abu Akleh’s killing and prosecute those responsible for what the network described as a “blatant murder.” The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation is also investigating the incident, but Israel has said it will not cooperate.

In a statement ahead of the one-year anniversary of Abu Akleh’s death, the network called on journalists and governments worldwide to act so that the “perpetrators are held accountable and brought to justice, to ensure that no other journalist pays the ultimate price for merely carrying out their duty.”

Meanwhile, Al-Jazeera has continued reporting on the Israeli occupation without the correspondent who defined the beat for a generation of TV viewers. In an essay published in 2021, Abu Akleh wrote about the city where she would die the following year, calling Jenin the embodiment of the Palestinian spirit. Today, the site of her death has become a shrine; the tree where she collapsed is covered in photos of the reporter who once walked the nearby streets, microphone in hand.

Journalists killed by the Israeli military

Credits

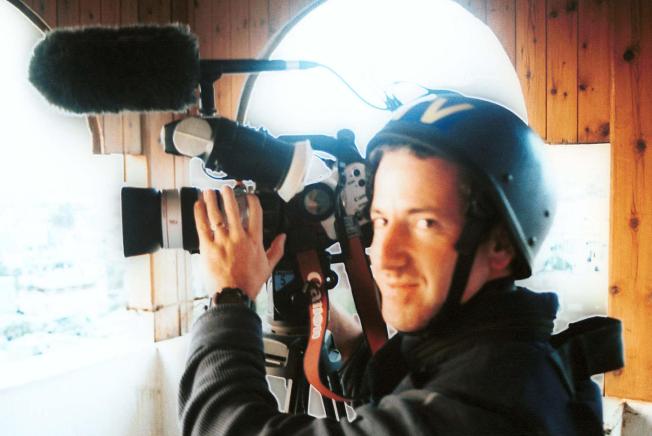

Orly Halpern is the reporter and analyst of this report. She is a Jerusalem-based investigative journalist and TV news producer who has worked across the Middle East and Africa and has reported from conflict zones, including in Israel and the Palestinian territories, Iraq, and Afghanistan. She has worked for global broadcasters and has written for major international outlets including Time magazine, The Washington Post, and Foreign Policy. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international relations and in Middle East studies and Islam from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She speaks English, Hebrew, and Arabic.

Naomi Zeveloff, CPJ’s features editor, edited this report. Prior to joining CPJ in 2020, Zeveloff reported for six years from Israel and the Palestinian territories, first as The Forward’s Middle East correspondent and later as a freelancer for outlets such as NPR, The Atlantic, and Foreign Policy. She was also previously The Forward’s deputy culture editor in New York. Originally from Ogden, Utah, she began her career in journalism in the American West, reporting for newsweeklies in Salt Lake City, Colorado Springs, Denver, and Dallas. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Colorado College and a Master of Arts in political journalism from Columbia Journalism School.

Robert Mahoney, CPJ’s director of special projects, also edited this report. Mahoney is a journalist, author, and fighter for press freedom who has been at the forefront of the struggle for press freedom, journalists’ safety, and the right to report since joining the Committee to Protect Journalists in 2005. From 1978 to 2004, Mahoney worked with the Reuters news agency in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. He headed news bureaus in Jerusalem, West Africa, and Germany, and also served as news editor for Europe, Africa, and the Middle East based in London. After a stint as a freelancer and journalism trainer he joined CPJ, where he helped lead the organization and expanded its reporting and advocacy, particularly around the intersection of technology and press freedom. He helped build an Emergencies Response Team to address the growing safety needs of journalists. He became deputy executive director in 2007 and executive director in 2022. He writes on the press and appears in print and media interviews as an expert on media freedom and threats to journalists globally. In 2022 he co-authored with former CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon The Infodemic: How Censorship and Lies Made the World Sicker and Less Free.

Samir Alsharif, a Jerusalem-based local journalist and production manager, provided additional reporting. Working in Arabic, English, and Hebrew, he has supported foreign journalists from a variety of international outlets for more than 12 years. He has overseen logistics, administration, and coordination efforts on multiple projects with National Geographic magazine, and has worked with book authors and on various films.

Sherif Mansour, CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program coordinator, also provided additional reporting. He is an Egyptian-American democracy and human rights activist. Before joining CPJ, he worked with Freedom House in Washington, D.C., where he managed advocacy training for activists from the Middle East and North Africa. In 2010, Mansour co-founded the Egyptian Association for Change, a Washington-based nonprofit group that mobilizes Egyptians in the U.S. to support democracy and human rights in Egypt. He has monitored Egyptian elections for the Ibn Khaldun Center for Development Studies and has worked as a freelance journalist. In 2004, he was honored by the Al-Kalema Center for Human Rights for his work in defending freedom of expression in Egypt. Mansour has authored several articles and conducted research studies on civil society and the role of the new media and civil society in achieving democracy. He was named one of the top 99 young foreign policy professionals in 2013 by the Diplomatic Courier. He received a bachelor’s in education from Al-Azhar University in Cairo and a master’s in international relations from the Fletcher School at Tufts University. He speaks Arabic fluently.

Emily Schaeffer Omer-Man provided expert review and additional research. She is an international human rights attorney with more than 15 years’ experience challenging Israeli military policies and practices on behalf of Palestinian litigants in Israeli courts and international tribunals. From 2005 to 2017 she served as senior counsel at the Michael Sfard Law Office and legal director of Yesh Din’s Security Forces Accountability Project, representing more than 500 victims of killing, injury, and other crimes committed by soldiers and border police in the West Bank, including east Jerusalem. She is an adjunct professor of human rights and the rule of law at American University and is regularly invited to lecture and comment on the application of international law to Israel’s occupation.

David Kortava fact-checked this report. Kortava is a journalist on the staff of The New Yorker. He has reported for the magazine on a range of subjects, including Russia’s “filtration camps” in eastern Ukraine — a recent cover story supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Editor’s note: After deadline, the IDF’s North American Media Desk responded to a CPJ fact-checking request about the role of Colonel Meni Liberty in overseeing a probe into Shireen Abu Akleh’s death. Liberty is a member of the chain of command of the unit the IDF identified as a possible source of fire that killed Abu Akleh. The response is below:

The IDF is composed of two types of brigades with key structural differences: ‘organic’ brigades and ‘regional’ brigades. An ‘organic’ brigade is responsible for its forces through a personnel framework, while a ‘regional’ brigade is responsible for the physical space in which the forces carries out operational activity.

During operational activities, the organic force is subject to the command of the regional brigade.

Hence, regarding the circumstances that led to the death of journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, the commander of the Menashe regional brigade was responsible for the command of the Duvdevan soldiers that had operated in the area. COL Meni Liberti, The commander of the Oz Brigade, an organic brigade, had investigated the incident with the understanding that he did not command the force that had operated in the area.

CPJ’s recommendations

The pattern of journalist killings by the Israeli military constitutes a grave threat to press freedom, undermining journalists’ ability to report the news freely and safely. CPJ calls on Israel, the United States, and the international community to implement the following recommendations to protect journalists, end impunity in the cases of killed journalists, and prevent future killings.

To Israel

- Open criminal investigations into the cases of three murdered journalists: Shireen Abu Akleh (2022), Ahmed Abu Hussein (2018), and Yaser Murtaja (2018).

- Guarantee swift, independent, transparent, and effective investigations into the potentially unlawful killings of journalists, which constitute possible war crimes; make public fact-finding assessments or other preliminary probes into all journalists killed or injured since 2001; and seek independent review of these probes for potential criminal investigations.

- Any and all credible investigations into attacks against journalists by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) or Israel’s security forces should follow international investigation standards, such as those set forth in the Manual on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary, and Summary Executions known as the “Minnesota Protocol.” The protocol establishes that under international law, the duty to investigate a potentially unlawful death entails an obligation that the investigation be prompt; effective and thorough; independent and impartial; and transparent.

- Allow human rights organizations, as well as U.N.-appointed investigators—including U.N. special rapporteurs and the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel—unrestricted access to Israel and the Palestinian territories to investigate suspected violations of international law by all parties. Acknowledge and implement their recommendations to improve the ability of journalists to report freely and safely.

- Review and reform IDF rules of engagement to prevent the targeting of journalists in the future, in line with the U.N.’s recommendation to stop the unwarranted use of lethal force. These revised directives should convey to all security forces, publicly and privately, that the use of lethal force against journalists—who are civilians performing their jobs—is prohibited, and make clear that forces must refrain from opening fire on individuals with press insignia.

- Fully cooperate with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into Abu Akleh’s killing.

- Cooperate with any International Criminal Court investigation resulting from recent legal submissions alleging war crimes against journalists by Israel’s security forces and a failure to properly investigate killings of media workers.

To the United States

- Provide an urgently needed comprehensive public update on the status of the FBI’s investigation into the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, who was an American citizen. The investigation was reportedly launched in November 2022 and there has been no public accounting as of May 2023.

- Leverage the U.S. partnership with Israel to:

- Secure Israel’s full cooperation with the U.S. Department of Justice investigation into the killing of Abu Akleh.

- Press Israeli authorities to review and reform IDF rules of engagement to prevent further killings of journalists.

To the international community

- The U.N. Commission of Inquiry should continue to press Israel on its recommendation that the rules of engagement be revised to stop the use of unwarranted lethal force.

- Governments, particularly allies of Israel, should hold Israel accountable to its international obligations to protect the safety of the press and for ending impunity for crimes against journalists in the Palestinian territories. Governments must also urge Israel to fully cooperate with any international inquiries into the killing or targeting of journalists by Israeli forces in the Palestinian territories.

- The Media Freedom Coalition, a group of more than 50 member states that pledge to support media freedom, should encourage Israel to end impunity in the killing of journalists and to revise IDF rules of engagement in order to prevent further journalist deaths.