Tough reporting earned Sheremet enemies in three countries

KIEV — Olena Prytula was sleeping so deeply that her mind would not be fully alerted to the real-life nightmare unfolding outside her door until she came face to face with it.

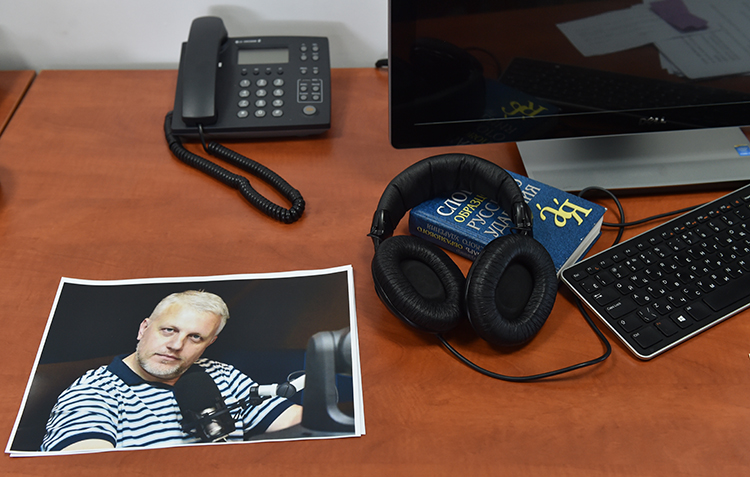

It was around 7:40 a.m. on July 20, 2016, and Prytula’s common-law partner, the Belarusian-born journalist Pavel Sheremet, had kissed her goodbye as he did every morning before driving her car to work at Kiev’s Radio Vesti, where he hosted a daily news program. Sheremet rarely altered his routine. And Prytula rarely missed his 8 a.m. show.

But on this day, with the sun shining in, Prytula, who is the owner, co-founder, and former editor-in-chief of the influential news website Ukrainska Pravda, dozed off. When a powerful explosion rocked her bed, scattered the birds outside her window, and set car alarms screaming on the street at 7:45 a.m., she said she almost didn’t get up.

“I came to the balcony to see what had exploded and where, but there was no sign of smoke and I couldn’t understand where it was coming from,” Prytula said. She told me she was crawling back into bed when “a thought came to my mind that we could report on what happened. And if Pavel was driving nearby, he would definitely stop and take a photo, or tweet it to talk about it later on the radio.”

Prytula said when she called his phone she received a message saying the number couldn’t be reached, so she figured he had forgotten to turn it on. She called five more times. Still no answer. She thought it was odd, but figured he was probably already in the studio preparing for his program.

But at the Radio Vesti office, Sheremet’s coworkers had not seen him and were wondering why he hadn’t shown up. Maria Shtogryn, a station presenter who often worked with Sheremet, said she tried calling him around 7:50 a.m. but reached the same automated message that Prytula heard. “We were surprised because he always came early before his program started,” she told me. She said she recalled thinking that maybe he was stuck in traffic.

Meanwhile, outside Prytula’s window, people were flocking to the intersection some 500 feet south of her apartment where Ivan Franko Street meets Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, a busy traffic and pedestrian crossing one block from the national opera house in the heart of the Ukrainian capital. She said her journalistic instincts kicked in. “I didn’t even wash my face, I just put on the first dress I saw and went out to the street,” she said.

Prytula said she found a crowd at the intersection and a charred, smoldering car that had been destroyed by what authorities would later say was an improvised explosive device. People were panicked, and debris was scattered across the street. The timestamp on the photo she took helps track her moves at the scene. At 7:56 a.m. she took a picture of the vehicle. It was difficult to discern the model, but a firefighter told her it was a Ford. Prytula said she thought to herself, “Thank God it’s not ours.”

But when firemen washed clear the wheel rims, she said, they revealed a Subaru—her Subaru CrossTrek.

Police officers didn’t know where the driver—Sheremet—had been taken, only that he had been removed from the vehicle. Prytula found him in an ambulance across the street, on a stretcher, covered with only his face visible. “I needed to look,” she said. “He was recognizable, but his face didn’t look alive.”

She said a paramedic cautioned her not to touch Sheremet because his leg, hanging on by tissues of skin, “was falling off.”

Moments later, he was pronounced dead.

***

Pavel Sheremet, a 44-year-old burly Belarusian by birth, lived and worked for extended periods of time in his native country as well as in Russia and Ukraine. He had a far-reaching network of friends who adored his wit and charm and respected the work he did as an investigative reporter, TV anchor, political commentator, and author.

He also had enemies. He was critical of authorities in each of those former Soviet states, where he cultivated close personal and professional relationships with powerful figures, including controversial ones. He had long been the target of harassment and threats because of his reporting—leading family, friends, colleagues, and investigators to say they believe the motive for his killing was most likely revenge for his professional activities.

There was hope in the beginning that Sheremet’s murder would be solved quickly. The case was a crucial test for Ukraine’s reformed, pro-Western government, and President Petro Poroshenko promised in a July 2016 statement to personally oversee “a transparent investigation.” He said no resource would be spared and assigned the country’s top investigative officials to the task. “It is a matter of honor to take all measures to solve this crime as soon as possible,” Poroshenko said.

But nearly a year after Sheremet’s death, the case seems to have gone cold. Critics blame authorities’ incompetence, negligence, or sabotage—or a combination of all three. No one has publicly identified two suspects seen on security camera footage planting the bomb. Crucial video evidence surfaced only after journalists published it; top police and security services officials have each alleged that the other destroyed video evidence; potential witnesses and Sheremet’s colleagues say investigators have not closely questioned them; and the national police chief first tasked with leading the investigation resigned. Sheremet and his Ukrainska Pravda colleagues apparently were under surveillance in the months before his death, but it’s unclear by whom, or why.

Furthermore, on May 24, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, who oversees the national police, claimed that an investigating officer had made a “mistake,” necessitating that all evidence be re-examined. Avakov did not identify the officer.

In a written statement provided to CPJ, Ukraine’s National Police director of communications, Ya.V.Trakalo did not directly respond to a question about the alleged police mistake.

Police have been slow to track down potential witnesses. It was only after the release in May of “Killing Pavel”—a documentary by the investigative reporting groups Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and Slidstvo.Info—that police interviewed Igor Ustimenko, a former SBU agent who is the only person publicly identified so far as in the vicinity before and at the time the bomb was planted.

The SBU, a successor of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic’s branch of the KGB, is one of the law enforcement agencies involved in the investigation. Poroshenko personally appointed Vasyl Grytsak as SBU chief. According to my contacts within Ukraine’s security apparatus who asked not to be identified because they are not authorized to discuss sensitive information about the agency, the SBU has struggled to root out Russian spies and agents with Russian sympathies since the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014.

Meanwhile, Interior Minister Avakov told a press conference in February that all indications point to Sheremet’s murder being a “contract killing, the order for which came from Russia.”

Russia has deflected Ukraine’s accusations. “As often happens in the realities of modern Ukraine, there are immediately those who in their minds poisoned by Russophobia ‘calculated’ a ‘Russian trace’ in this brutal massacre,” the Russian foreign ministry said in response to the accusations by Ukrainian officials in the aftermath of the murder, according to Russian state media.

In my dozens of interviews conducted over several months, investigators said they have nothing beyond circumstantial evidence to support Avakov’s theory of a Russian contract killing, and are still pursuing three main “tracks” or lines of inquiry in Sheremet’s murder—a Belarusian track, a Russian track, and a Ukrainian track, based on the journalist’s conflicts with, or criticisms of, authorities and power players in each country. Within each track, investigators say they are also looking into whether conflicts in Sheremet’s personal life, including possible financial problems, were a factor. They said they haven’t ruled out that Prytula was the intended target, though they say that appears less likely.

Poroshenko, speaking to journalists wearing T-shirts adorned with the question, “Who killed Pavel?” during a May 14 press conference in Kiev, said he was “dissatisfied” with the results of the investigation. “I’m not happy that we still have not caught the killer, and he is not held accountable,” the president said.

Svetlana Kalinkina, a Belarusian journalist and longtime friend of Sheremet’s with whom she co-authored Accidental President—a book about Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko—told me in Minsk that immediately after Sheremet’s death, a colleague said to her, “Thank God this happened in Ukraine and not Russia or Belarus, because if it happened in either of those places we would never know who was behind the murder.”

It would seem they judged wrongly, she said.

In fact, Kalinkina is one of more than a dozen family members, friends, and colleagues interviewed for this report who say they suspect a Ukrainian connection to Sheremet’s killing, citing his past work and an environment of hostility and suspicion toward critical journalists in Ukraine at the time.

Those who challenged the Ukrainian authorities, investigated their wealth and conflicts of interest, or questioned the official narrative on the conflict with Russia-backed separatists in the east were physically assaulted, harassed, or allegedly spied on by authorities, or else targeted in coordinated campaigns online by pro-government or nationalist trolls to discredit or intimidate them, according to numerous journalists who were interviewed for this report and for my coverage of Ukraine for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL).

Some high-ranking government and security officials, including Avakov, supported the attacks publicly, writing on their personal Facebook pages that the journalists deserved what they got.

Katya Gorchinskaya, a former journalist turned chief executive officer of Ukraine’s independent Hromadske TV channel, told me the situation reminded her of the 1990s and early 2000s, when journalists were assaulted and murdered with impunity.

Ukraine had a poor record when it came to solving crimes against journalists well before the murder of Sheremet. At least seven journalists have been murdered in direct retaliation for their work—five with complete impunity—since 1992, according to CPJ research. Most of those covered political corruption, organized crime, or the affairs of powerful oligarchs.

One of those cases continues to haunt Ukraine, and Prytula especially. In September 2000, the Ukrainian investigative journalist Georgy Gongadze, with whom Prytula founded Ukrainska Pravda, went missing after leaving her Kiev apartment to go home to his wife and two children. Two months later, on November 3, his body was found in a forest outside the city, doused with a chemical to speed up the decomposition. It had been decapitated and showed signs of torture, according to news reports and official police information.

The case was as high profile as they come, with then-President Leonid Kuchma implicated after a recording allegedly of him discussing ways to get rid of Gongadze was leaked to the press. Gongadze had been critical of the president in Ukrainska Pravda and on television. Kuchma denied any involvement in the murder. He said in 2011, after a criminal case was opened, that he was prepared to “go through hell” to prove his innocence. The case was closed months later and no charges were brought against the former leader. Gongadze’s killer, a former police general, and three low-level officer accomplices have been prosecuted, but no mastermind has been brought to justice.

The current conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which according to a United Nations Human Rights Office report has killed over 10,000 people and is now in its fourth year, has exacerbated problems for the press. Both countries have banned journalists from entry to their respective nations, and Russia in some cases has detained journalists. They have also pressured, blocked, or closed critical news outlets.

And each side has unleashed on each other government-backed networks of trolls and bots—automated social media accounts. Russia has its Internet Research Agency and powerful state-run media outlets and Ukraine, under the auspices of the Ministry of Information, has the i-Army. The man who headed the ministry until May—former journalist Yuriy Stets—is a close ally of Poroshenko.

I joined the group’s newsletter in 2015, using my own name, to see what sort of orders were issued. The info warriors were encouraged to call out publicly any reports spreading “Russian propaganda” online, such as those which used the term “rebel” to describe Russia-backed separatists or “Ukraine crisis” to describe the conflict. The i-Army’s preferred term for the Russia-backed forces is “terrorists” and for the conflict, “Russia’s war against Ukraine.”

But the i-Army’s online offensive was mild in comparison to the Ukrainian ultra-nationalist group that came after it.

In May 2016, a pro-government website called Myrotvorets, or Peacemaker, published the names, affiliations, and contact details of more than 5,000 Ukrainian and international reporters and fixers who applied for press accreditation to work in separatist areas, and labeled them “terrorist collaborators.” Self-proclaimed Ukrainian patriots used the information to identify targets for menacing text messages and emails, some of which were sent anonymously, with threats of physical violence and death. Ekaterina Sergatskova, a freelancer who works with Hromadske TV and Ukrainska Pravda, told me she received an SMS threatening the life of her and her child.

Instead of heeding public calls to investigate the threats, Avakov, the interior minister, defended Myrotvorets on his Facebook page, saying he would side with the site before reporters, whom he referred to as “liberal separatists.”

The Myrotvorets website says it is directed by a Ukrainian who goes by the name Roman Zaytsev. Zaytsev’s Facebook page, on which a mask conceals the face in the profile picture, lists his occupation as director of the site and his past occupation as “department head” at the SBU. A spokesman for the security service told me it was not cooperating with the site, nor did it ever employ anyone by the name of Roman Zaytsev.

According to journalists who have investigated Myrotvorets, its operations are influenced, if not controlled, by a populist lawmaker and interior minister adviser, Anton Gerashschenko, who has been unwavering in his public support of the site. Confronted directly in an interview in August 2016, Gerashschenko winked while saying he had nothing to do with the site. He then patted my knee and told me, “yes,” I, too, was a separatist collaborator, because my name was on the Myrotvorets list.

CPJ, on May 24, 2016, urged Poroshenko to condemn Myrotvorets and the comments made by Gerashschenko and Avakov. The president did so in his annual press conference on June 3, but only when pressed by reporters—and with a caveat. “Unfortunately, I have information that some of these journalists [listed in the leaks] have prepared negative comments or negative articles about Ukraine,” Poroshenko said. “I kindly ask you: please, do not do that.”

It was against this backdrop that Sheremet was working at Ukrainska Pravda and Radio Vesti, where he started in 2015 and eventually took over the daily morning show. He worked at both organizations at the time of his death.

Both of those could have made him a target for certain groups, several colleagues suggested. Some nationalistic Ukrainians, including authority figures, viewed Radio Vesti as a Russian propaganda outlet because its owner, Ukraine’s former finance minister Oleksandr Klymenko, was an ally of deposed President Viktor Yanukovych. The pair fled to Russia in February 2014. (Radio Vesti ceased transmission in Ukraine in February 2017 when the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council, which regulates the country’s airwaves, did not renew the station’s broadcasting license, Klymenko said in an emailed statement.)

Others were disapproving of Ukrainska Pravda because of its critical and investigative reporting. Igor Guzhva, chief editor for the Strana news website (and previously editor-in-chief of Vesti News, which ran Radio Vesti), told me that in the months before Sheremet’s death, he started to notice Ukrainska Pravda “taking a position of skepticism of the current government,” which continues today. He said the site and its journalists were publicly attacked in the weeks before Sheremet’s murder by pro-government trolls. That is notable, Guzhva said, “because Ukrainska Pravda was one of the most important media during [the revolution that deposed Yanuovych] and is viewed as having helped this new government come to power.”

Sheremet’s last column for Ukrainska Pravda, published three days before his murder, followed this critical line. In it, he warned Ukrainian authorities of the unchecked power of “deputy-battalion commanders”—a reference to militia leaders-turned-lawmakers—“and the people in camouflage now, if not already above the law, then on orders are capable of paralyzing the operation of any law”— members of the far-right nationalist battalions, some of which have been accused by human rights groups of torture and war crimes during the conflict with pro-Russia separatists. The former Azov battalion commander and now the group’s political leader, lawmaker Andriy Biletsky, who Sheremet praised for having mostly kept his battalion in check, was among the last people to see the journalist alive.

This complex web of affiliations has led to rumors and counter-rumors about Sheremet’s murder. One unsubstantiated claim online, the origin of which I traced back to an April 2013 article in Ukraine’s independent Obozrevatel news website, claimed Sheremet was an undercover agent of Russia’s Federal Security Service, or the FSB, the main successor agency to the KGB. Ukrainian trolls claimed Moscow killed Sheremet because he switched sides, and Russian trolls claimed Kiev killed him because they had discovered he was a spy.

Belarus Days

A full accounting of people who may have had a motive to kill Sheremet must go further back, to the prominent work he did in his native Belarus. In the course of that work, one of his close associates disappeared and was eventually declared dead.

Sheremet—raised by his parents Grigory, a Minsk city government official, and Lyudmila, a scientist at Belarus’s National Academy of Sciences—got his first taste of journalism while working for a bank in 1992, when he appeared as a consultant on an economic TV news program. By 1994 he was the producer and anchor of “Prospekt,” a weekly news and analysis program on Belarus state-run Channel One.

“Pavel belonged to a category of Soviet-era children who had time to read books, study languages and dream,” said Saken Aymurzaev, a close friend and colleague of Sheremet’s at Radio Vesti who lived three floors below the journalist in Kiev. “They were an intellectual Soviet family.”

Sheremet’s rise coincided with that of Alexander Lukashenko, who was then deputy to the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus. He was also a fan of “Prospekt.”

“Sheremet was actually Lukashenko’s favorite journalist then,” Kalinkina, his friend and co-author, said.

That allowed Sheremet some access to Lukashenko, who became president in July 1994. He quickly developed strong relationships with those in Lukashenko’s inner circle.

But the relationship began to fizzle as Sheremet’s popularity grew and he became more critical of Lukashenko on his program. As he moved to consolidate his power, the president ordered “Prospekt” off the air in April 1995, one week before a referendum that increased the authority of the presidential office. Sheremet was out of a job, but not for long.

He became editor-in-chief of Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta, a small but prominent business-focused Belarusian newspaper. Under Sheremet, it transformed from a business outlet to a more politically- and socially-minded newspaper. “It was a sort of school for Belarusian independent journalists, led by Pavel,” Kalinkina said. “When he wasn’t doing his own reporting, he was training others.”

As it grew and began garnering more attention for its coverage of anti-government rallies and criticism of Lukashenko’s Soviet-style political tactics, the government saw it posed a threat, Kalinkina said.

Sheremet’s association with the paper earned Grigory, Sheremet’s father, flak and glares from some of his colleagues at his city government job, but the father stood up for his son. “Grigory was very protective of Pavel. He was like a tiger,” Lyudmila Sheremet said of her late husband.

Sheremet was happy with the direction he took Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta, but “his personality shined on TV. He wanted to return to it,” Kalinkina said.

An opportunity soon arose when Russia’s state-run ORT television channel offered him the position of Minsk bureau chief, which included him hosting its leading news programs “Novosti” and “Vremya.”

***

While working for ORT in June 1997, Sheremet clashed with Lukashenko, who was lobbying to change Belarus’ Independence Day from July 27, the day the country declared its post-Soviet sovereignty, to July 3, marking a Soviet-era holiday. Foreign ministry officials accused Sheremet of insulting the president and the nation after the journalist called the proposal “President Lukashenko’s idea” during a news broadcast. The officials permanently revoked his special events accreditation for “biased reporting,” CPJ reported at the time.

In July of that year, Sheremet angered Lukashenko further when he aired a report about border smuggling, Sheremet’s mother said. Belarus charged Sheremet and his cameraman, Dmitry Zavadsky, with illegally crossing an unguarded section of Belarus’s border with Lithuania, “exceeding their professional rights as journalists” and participating in a conspiracy.

In January 1998, a court found Sheremet and Zavadsky guilty on all charges, handed down suspended sentences of two years’ imprisonment and 18 months’ imprisonment respectively, and ordered them to pay a fine.

Standing in her Minsk living room beside a photograph of Sheremet and Zavadsky, who has a camera slung over his shoulder, Lyudmila Sheremet said the saga was part of Lukashenko’s “revenge” against her son for embarrassing him. “The point was to get back at Pavel and to scare other independent journalists,” she said.

The persecution brought more attention to Sheremet’s reporting. CPJ honored him with an International Press Freedom Award in 1998 for his unflinching resolve.

Despite the pressure from authorities, Sheremet and Zavadsky went to Chechnya in 1999 to work on a four-part documentary, “Chechen Diary,” about the Second Chechen War. Filming wrapped in May 2000 and the first part was aired in July. CPJ documented at the time how, on their return, Zavadsky received threatening phone calls. On July 7, Zavadsky was supposed to meet Sheremet at Minsk National Airport but he never appeared.

Zavadsky’s friends and colleagues feared he had been kidnapped and killed, possibly because he had footage that showed Belarusian security agents fighting alongside Chechen rebel forces, people in Belarus, who were not named, told CPJ at the time. On November 28, 2003, a district court in Minsk declared Zavadsky officially dead.

Sheremet believed Belarusian intelligence agents were behind Zavadsky’s abduction, his mother said. Few leads would surface over the next two years, until two men from a special police force were convicted of abducting Zavadsky. A Zavadsky family lawyer called them scapegoats and insisted that responsibility rested with the Belarusian government, as CPJ reported at the time. Sheremet “never stopped looking” for whoever ordered the murder of his friend, Lyudmila Sheremet said.

Soon, Lyudmila Sheremet said, her son came to understand that he “wouldn’t be allowed to work freely in Belarus anymore.” He left “Novosti” and “Vremya” and relocated to Moscow in 2000.

Russia Days

In Moscow, Sheremet became a Russian citizen as well as ORT’s lead for documentaries and special projects. But his arrival in Moscow coincided with the rise of Vladimir Putin, who succeeded Boris Yeltsin as president in 2000.

One of the first things Putin did was go after the critical, independent media, consolidating the government’s control over the information sphere. NTV, an independent news channel that had risen to prominence for its investigative reporting, and which hosted a program that poked fun at the new president using a puppet lookalike, was among Putin’s early targets. Not long after his inauguration, security services raided its offices and confiscated documents. Critics condemned the move and said it was politically motivated because the channel criticized Putin during his election campaign. Government pressure persisted and in 2001 the state-controlled Gazprom-Media took over the channel.

Similar cases followed as the Kremlin began building a powerful propaganda machine. As Russia’s media landscape shrunk, those journalists who refused to be told how and what they should report at state-owned outlets left and joined what few independent publications were left. But Sheremet stuck it out at ORT, which in 2002 became known simply as Channel One, and found a way to continue his work for the most part without censorship, friends and colleagues who worked with him or interviewed with him as guests on his programs said.

“From the very beginning, [Sheremet] was a smart centrist, an explorer of political life,” Matvei Ganapolsky, one of Russia’s most popular political commentators and a Ukrainian by birth who appeared frequently in Sheremet’s reports, said. “That allowed him to work on Russia’s main channel.”

Despite working in Moscow, Sheremet remained interested in his native Belarus and returned frequently, even after attackers beat him while he covered the Belarusian elections in 2004. In 2005, he set up the newspaper Belorussky Partizan as way of keeping a foothold in his motherland and to train the next generation of Belarusian journalists, Kalinkina said.

But the publication irked Lukashenko. Lyudmila Sheremet and others say they believe Belorussky Partizan and Sheremet’s continuing criticism of the government played a large part in what happened later in 2010.

In March of that year, Sheremet was summoned to the Belarusian embassy in Moscow. Lyudmila Sheremet said when he got there, without any explanation, a diplomat handed him an official letter explaining that he had been stripped of his Belarusian citizenship, and demanded he hand over his passport. “The situation reminds me of the Soviet period…when dissidents were deprived of Soviet citizenship without any court decision and kicked out of the country,” Sheremet told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty at the time.

Under Belarusian law, a citizen cannot be deprived of citizenship under any circumstances. There is only one way it could have happened, Kalinkina told me: “It was a special decree by Lukashenko.”

Lukashenko never commented publicly and his administration did not respond to CPJ requests for comment. Lyudmila Sheremet said that revoking Sheremet’s citizenship was one of the most “sinister” things Lukashenko could have done to him.

Sheremet held out hope that one day he would be able to sue the state in court for depriving him of citizenship, Kalinkina told me. “He was waiting for Lukashenko to leave office,” she said. Kalinkina recalled how when Sheremet felt the need to connect with his compatriots he would go to the Kiev railway station and meet a train arriving from Minsk. “He would watch people file off the train and look for anyone he knew. If he saw someone he knew, he would grab them and take them around Kiev, show them the city and talk their ear off all day, over breakfast, lunch and dinner,” she said.

Lyudmila Sheremet said she feared she might not be allowed to bury her son in Belarus because of his non-citizen status, so she was relieved when she heard from Belarusian authorities that Sheremet could be buried in Minsk.

Lukashenko acknowledged the animosity between himself and Sheremet, but said he respected the journalist, Lyudmila Sheremet told me.

Ukraine Days

In 2011, Sheremet decided to relocate to Kiev, telling colleagues he was worried about the worsening media environment in Russia, said Saken Aymurzaev, a close friend and colleague of Sheremet’s. Sheremet believed that Russia was heading in a similar direction as Belarus in the late 1990s, as Putin intensified his crackdown on critical press, free speech, and opposition activists. Aymurzaev recalled Sheremet saying that his superiors had begun to try to censor him.

But there was also a new love interest in Ukraine—Prytula. The two met in 2008, when Sheremet came to Kiev to cover a parliamentary crisis and to talk up Belorussky Partizan, which he thought of as a sort of sister publication to Ukrainska Pravda. “That was the only thing he could have said to convince me to talk to him,” Prytula said.

However, Prytula admitted, there was something else that helped persuade her. “Among people of my generation the name Sheremet carried such a huge meaning and was well known,” she said.

After that meeting, and as his marriage dissolved, Sheremet visited Kiev with greater frequency. Sheremet liked the access he found he could get to high-profile people in politics, business and society in the city. “Unlike Russia, here you don’t have to wait for 20 years for a minister to respond to your request,” said Aymurzaev, Sheremet’s longtime friend.

Sevgil Musayeva-Borovyk, chief editor of Ukrainska Pravda, where Sheremet began working as a columnist in 2012, said that Sheremet’s prominence made doing so easier. “Nobody ever declined an interview with Pavel,” she told me, adding that they would often drag on, sometimes for hours, and involve some kind of unexpected twist.

But Kiev, a city of just four million people—about 10 million fewer than Moscow—sometimes was not enough for Sheremet, Aymurzaev said. “Pavel suffered because he was not able to find a job on the scale of the one he had in Moscow,” he said.

Three years after his move, Ukraine’s widespread protests and ensuing revolution presented him with a challenge worthy of his talents—one that would put him in conflict with Moscow.

It was during the protests that I first met Sheremet. It was the morning of November 30, 2013, and riot police had just beaten and chased scores of demonstrators from central Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, up the hill to St. Michael’s Monastery. Sheremet was energetic but his eyes looked heavy after a long night. I asked him his thoughts on what had just transpired while he fired off a tweet from his phone to his nearly 200,000 followers.

“Unfortunately, I had a feeling something like this would happen,” he said. He predicted that the authorities’ brutality that morning would transform the protests into a revolution. Of course, history would prove him right. When the revolution began, Sheremet was smack in the middle of it.

“He was on Maidan every day and night. He always came home smelling like the fires that burned on the square,” Prytula told me, using the colloquial term for the main square that served as the nerve center of the revolution. Surrounded by makeshift meters-high barricades, Maidan hosted field kitchens and a camp for thousands of protesters, a stage, a medical center, an information center, and more. Its inhabitants were kept warm with steaming bowls of borsch and, of course, barrel fires.

Sheremet, who at the time was working for Public Television of Russia, or OTR, emphasized in his reports the determination of average Ukrainians fighting to free themselves from Moscow’s grip and the brutality of then President Viktor Yanukovych’s regime—more than 100 protesters were killed in clashes with police before the former leader fled in late February 2014, according to reports. His reports stood in contrast to most on Russia’s state-run news programs, which painted Ukraine’s revolutionaries as bloodthirsty far-right nationalists and the uprising as a coup backed by a Russophobic Washington.

Often Sheremet would interview figures such as Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, a close friend who would berate the Kremlin on air for its meddling in Ukraine. (Nemtsov was assassinated in Russia on February 27, 2015.)

Those segments, along with his critical commentary, are likely what got Sheremet into trouble with Russia’s censors. Prytula, recalling Sheremet’s account, said that in May 2014, Alexey Gromov, the former Kremlin press secretary, then a deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration, contacted OTR editors to demand Sheremet be taken off the air.

At first, Sheremet’s editors in Moscow proposed a two-month vacation, hoping the Kremlin would forget about him. But Sheremet didn’t find that an agreeable solution. On July 17 that year, he wrote in a Facebook post that he had quit OTR, saying he was being “hounded.” He denounced Russia’s military actions in Ukraine. “I consider the annexation of Crimea and [Russia’s] support for separatists in eastern Ukraine and bloody adventures a fatal mistake of Russian politics,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Russian service quoted him as saying.

OTR declined my request for comment. CPJ attempted to contact the Kremlin press office for comment, but the fax numbers listed on its website did not work.

Threatening environment

The next year, while working for Ukrainska Pravda and Radio Vesti, Sheremet reported being surveilled in Ukraine, and confided that he was nervous about travel to Moscow, friends and colleagues said.

Sheremet and Prytula told friends and police in November 2015 they had seen a car parked outside their building. For days, three or four people at a time sat inside with the windows closed. At one point, Sheremet walked up to the car, tapped on the window, offered tea to the men inside, and asked what they were doing, Prytula said. Surprised, the men didn’t answer and drove away. But they returned the next day, and for several days after that in different vehicles.

Prytula said she and Sheremet recalled that their friend, Sergey Leshchenko, a former investigative reporter for Ukrainska Pravda who became a lawmaker in 2014, had recently accused Avakov, the interior minister, and another politician of spying on him. They denied the allegations. Prytula said she called Leshchenko seeking advice and asked him to come check out the vehicles.

Together, Prytula, Sheremet and Leshchenko called the police, who came to the apartment, followed by Gerashschenko, the Avakov adviser and lawmaker thought to be behind the Myrotvorets website, to question the men in the car. Prytula said the officers and Gerashschenko told Leshchenko afterward that the men said they were staking out a brothel for a private security company, which they said they couldn’t name. According to Prytula, when she told Gerashschenko that she didn’t believe his story, he told her she and Sheremet weren’t being surveilled—at least not by the police. He suggested Prytula “ask the SBU.”

Gerashschenko confirmed that he went to Prytula’s apartment and told me he more or less remembered it the way Prytula had. He said he had spoken with SBU chief Grytsak about the incident and recalled Grytsak saying, “We’ve no idea about [the surveillance].”

Grytsak’s office declined several requests to be interviewed for this report.

Prytula said she also called reporters from Schemes, the investigative unit of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Ukrainian service, who looked into the ownership records of some of the vehicles outside her apartment and discovered that many of the plates didn’t correspond with the vehicles, which the unit said suggested the cars were being used for surveillance.

In another incident in March 2016, a package was sent to the Ukrainska Pravda office, said Prytula and Musayeva-Borovyk, the Ukrainska Pravda editor-in-chief. It contained detailed information about the work of Ukrainska Pravda journalists, and Musayeva-Borovyk and Sheremet, in particular, they said. Musayeva-Borovyk added that some of the details in the documents came from discussions they had in phone calls and private Facebook and Viber messages, suggesting their mobile devices and social media accounts were being monitored. The information, Musayeva-Borovyk said, talked about Ukrainska Pravda journalists investigating members of the presidential administration and the illegal smuggling of coal between government and non-government controlled territories in war-torn eastern Ukraine. She said her sources in law enforcement told her that this sort of detailed logging was something often done by members of the SBU. Musayeva-Borovyk said knowing that someone was so closely following their work and listening in on their conversations scared them.

At the February press conference on the Sheremet investigation, Avakov said that agency officials told him the SBU was not watching Prytula and Sheremet.

The director of communications for police told CPJ that investigators “did not find any confirmation [that Sheremet was surveilled] but are still dealing with it.” The SBU did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment.

Pavel’s last days

Family and friends of Sheremet said that in the weeks before his murder they noticed a change in the journalist’s behavior and said he appeared stressed. Kalinkina said that on what would be his last visit to Minsk, two weeks before his death, Sheremet’s mood turned “darker.”

“My feeling is that, in the time before his death, he felt a sort of disillusionment about the Ukrainian Maidan revolution, because he hadn’t seen real change afterward,” Kalinkina told me.

Sheremet also had three potentially key meetings during that same time period, which family and friends say investigators should look at more closely:

1. Oleksandr Klymenko. On June 10, Sheremet traveled to Moscow, in part to celebrate the 20th birthday of his daughter, Elizaveta. But he also arranged to meet Klymenko, the ally of deposed President Yanukovych and owner of Radio Vesti. The trip came at a time when Sheremet had become increasingly fearful that “something could happen” when traveling to Moscow, Prytula said without elaborating. Prytula confirmed Sheremet and Klymenko met in the Russian capital. As did Elizaveta Sheremet, who said in an interview over Skype that in the car before the meeting, her father was “not quite himself” and told her he was on his way to meet the “businessman on the run.”

“He was pretty nervous. It wasn’t my father’s usual state. He didn’t ask me to go along like he usually would,” she said. Her father did not elaborate on why he was so nervous or say what—if anything specifically—was bothering him, she said.

Prytula, Sheremet’s friend Aymurzaev, and Ukrainska Pravda’s Musayeva-Borovyk all said Sheremet told them he wanted to get a feel for Klymenko’s mental state and a sense of what the future might hold for the news outlet, and that Klymenko wanted to speak with Sheremet about taking over the job of editor-in-chief of Vesti News and helping him find a way to return to Kiev. Klymenko, a devout and somewhat radical Russian Orthodox Christian believer, had hoped, according to Aymurzaev, that Sheremet could help rehabilitate his image in Ukraine, which could help allow Klymenko to return.

“Pavel came away disappointed, and he said that Klymenko suffered from orthodoxy of the brain,” Aymurzaev said, adding that Sheremet turned down the offer to head Vesti News before he returned to Kiev.

Klymenko declined my request for an interview. In an emailed statement he declined to comment on his meeting with Sheremet.

2. Vladimir Kara-Murza. In another meeting—three days before his death, on July 17, in Kiev—Sheremet and Prytula met Vladimir Kara-Murza, the Russian opposition activist and Putin critic. Kara-Murza, in an interview by phone from Washington, said the three discussed the film Kara-Murza was making about their mutual friend, Nemtsov. Kara-Murza, who says he has been poisoned twice in apparent attempts to silence him, speculated that the friends’ close association with Nemstov before his assassination may have been a motive for Sheremet’s killing.

Kara-Murza also said that Sheremet, during their meeting, recounted a story about being pulled over by a police officer for no apparent reason while in Moscow. Elizaveta Sheremet did not recall this happening while she was with her father, but said it is possible it occurred later. Kara-Murza said Sheremet told him the police took his documents, wrote down his personal details, then drove away without providing an explanation as to why they stopped him. Sheremet, Kara-Murza said, told him he “felt strange” about the incident.

3. Andriy Biletsky. Sheremet had one more potentially significant meeting just hours before his death. Around 11 p.m. on July 19, he met with Biletsky—the far-right former Azov battalion commander he discussed in his last column—and five of his colleagues outside his apartment. Biletsky declined several interview requests for this report, but he and Azov member Serhiy Korotkykh, a Belarusian to whom Poroshenko awarded Ukrainian citizenship for fighting on Kiev’s side in the conflict, were interviewed in the “Killing Pavel” documentary. In it, Biletsky and Korotkykh said they persuaded Sheremet to meet them so they could get his advice on a protest the following morning. The meeting lasted about 10 to 15 minutes.

Many of Sheremet’s colleagues told me they hope investigators will also explore the meeting with the Azov men. Some said their presence at the scene and their reputation for violence raises questions. But they said they worry that the close relationship between the Azovs and Avakov, who has publicly supported the group, means the Azovs are likely to be treated with favor.

When I spoke with Korotkykh in May, he told me that he went to the police the day of Sheremet’s murder. He said he was questioned by prosecutors the following day, and believed his testimony was enough to have him cleared. He said he decided to go to the authorities immediately because Sheremet was a “friend.”

Two months later, the SBU came to him with more questions, and then went to the press with the idea that the Azov members were being examined as suspects, Korotkykh told me. He claimed this was done “to send the investigation in the wrong direction.”

Asked point-blank if he or any of his Azov colleagues were involved in any way in Sheremet’s murder Korotkykh answered emphatically, “No.”

In a statement, the Main Investigations Office of the National Police told me the Azov group was questioned “as witnesses…about the circumstances of their meeting with Sheremet on the previous day before the murder.” Ukraine’s director of communications for police denied in a statement to CPJ that investigators are obstructed in any way from questioning and investigating the Azov representatives.

‘A professional hit’

The meeting with Biletsky and the Azovs relates to another, highly significant development.

An Azov security guard with the group that night, named only as Kostya, said in the documentary, “Killing Pavel,” that as they left, they noticed two vehicles in the street and a man standing at the entrance to a tunnel. One of the cars, a Skoda, was later found to have been driven by former SBU agent Igor Ustimenko. For several hours, Ustimenko and a person who appears to be the driver of the second vehicle are seen in security footage obtained for the documentary walking back and forth between Sheremet’s and Prytula’s apartment and their vehicles. At one point they are seen together.

Ustimenko was found with the help of a researcher from the open-source investigative group Bellingcat, which identified the license plate of the Skoda seen in security camera footage. He told the journalists he was at the scene but denied knowing about the murder or seeing the suspected assassins. He said he was hired as private security to protect someone’s children.

The SBU confirmed after the film’s release that Ustimenko worked for the agency until 2014.

Authorities said on May 15 that they had questioned Ustimenko, but did not provide any specifics to journalists about what he told investigators. The director of communications for police told CPJ in June that officers are still investigating why the former agent was near Sheremet’s apartment that night.

Ustimenko’s identity and presence at the scene was not uncovered by the official investigation. Yet, authorities looking into the murder had access to strong resources, including experts from the FBI brought in to help conduct forensic analysis, Poroshenko, Ukraine’s National Police, and the U.S. Embassy confirmed.

“All of the specialists who must be [at the scene] when something like this happens were there that day,” Khatia Dekanoidze, the national police chief at the time, who was among the first officials on the scene and was appointed by Poroshenko to personally lead the investigation, said.

However, Dekanoidze said, there were few leads from the get-go. “It was very well planned and professional. [The killers] left minimal evidence,” she said.

The police presented a summary of their findings in Kiev on February 8, 2017. At the press conference, Dekanoidze’s successor, National Police Chief Serhiy Knyazev, along with National Police Deputy Chief and Investigation Department Head Oleksandr Vakulenko and Interior Minister Avakov, said that around 35 investigators from the Interior Ministry, National Police, SBU, and three state prosecutors had been working on the case and that more than 1,800 interviews had been conducted, 150 terabytes of video footage had been reviewed from more than 200 security cameras, and 280 evaluations had been carried out of Sheremet’s published reports, columns and radio and television programs.

The little new information officials presented included video footage of a man and woman seen by several security cameras staking out the neighborhood where Prytula and Sheremet lived from July 15 to July 19, and outside his apartment on the morning of July 20. Footage showing what appears to be the same two people in disguise placing the bomb on the underside of the Subaru hours before the car exploded was leaked to the media days after the murder.

Also at the February press conference, Knyazev and his colleagues provided analysis of the explosive device—a modified MON-50 anti-personnel mine—as well as a video showing a reenactment of the blast.

“It was a self-made standard combat mine that you can find on every corner of this country at war,” Knyazev told me in our interview, throwing his hands in the air. “The skill level of the assassins was about that of a first-year army soldier [in any army] … It was a very simple but very effective [method of] murder.”

The only other new information to be made public since then comes from the documentary. Besides Ustimenko being outside Sheremet’s and Prytula’s apartment, security camera footage filmed that same night showed two people who planted the bomb wearing dark clothes—not light gray clothes as they appeared in the poorer-quality infrared footage released by police—walking toward the Subaru on Ivan Franko Street. A large emblem marks the back of the man’s hoodie.

According to the official investigation, the man and the woman are “persons of interest” but are not officially labeled suspects. Police have not publicly identified them.

Pressed for more information about the pair in an April interview with me, Knyazev appeared to suggest that investigators may have some idea about who they are, but could not share the details with reporters because it could scare them into hiding or fleeing.

Dekanoidze said she doubted investigators have identified anyone involved, and suggested Knyazev was posturing to appear as though his team was sitting on more information than had been made public so as not to seem incompetent. She said the information presented on February 8 amounted to all of the evidence gathered by the time she resigned in November.

Dekanoidze said she left her post because her efforts to reform the national police were being blocked by her superiors. She said her superiors did not try to impede her work on Sheremet’s case specifically. Police officials did not reply directly to her remarks at the time of her resignation or in interviews for this report, saying only that she did well in carrying out her duties.

Those closest to Sheremet and who could possess important information, said investigators have ignored their inquiries or failed to follow up with them after initial interviews. “At first I got the impression that [the authorities] were interested in conducting a thorough investigation. But with time I saw that their interest was getting less and less,” Prytula told me. “The majority of my friends, who told me that policemen came to their apartments asking if they had seen or heard anything notable, said that their questions were quite superficial.” She said police had not interviewed her for six months.

Lyudmila and Elizaveta Sheremet told me in separate interviews prior to an April 21 meeting they had in Kiev with President Poroshenko, SBU head Grytsak and two other law enforcement officials inside the presidential administration, that nobody from the investigation has contacted them since the days after Sheremet’s death. Nine months later, and only at their own initiative, did they meet with these officials, who did little more than offer condolences, Elizaveta Sheremet said.

Asked about alleged incompetence by investigators, the director of communications for police told CPJ the investigation is complicated and that details cannot be made public to avoid harming the investigation.

Some of Sheremet’s friends and family said their gut feeling at first was that the Russian security services were behind it, but they said they quickly gravitated toward the belief that a Ukrainian hand was behind the killing. That is partly because while Sheremet had been critical of Putin and Russia’s actions in Ukraine, he hadn’t been a major influencer in Moscow for years, they said; but mostly because of the public harassment and intimidation of Ukrainska Pravda leading up to July 20.

However, Prytula, unlike many of her colleagues, said she has not ruled out a Belarusian or a Russian hand in his murder, and believes they should be investigated with equal vigor. She told me similarities between Sheremet’s case and the murder of Denis Voronenkov—a former Russian lawmaker turned Kremlin critic who was assassinated in Kiev in February after defecting to Ukraine—made her reconsider Russian involvement.

Most people within Ukraine’s law enforcement, whom I spoke with for this report, say they consider the least likely scenario to be that Sheremet was killed by Belarusian authorities in revenge for his past work, because he had been away from the political scene there for so long.

The most likely scenario, they all agreed, is that Sheremet was killed at the behest of the Kremlin or Russia’s security services to further destabilize an already war-torn Ukraine, but they all came up short when asked to provide anything more than circumstantial evidence. In some cases, they became disgruntled when pushed for specifics.

When Knyazev, the chief of National Police, was pushed for more information, he huffed and pointed at the clock, saying that he had “14 minutes” left to speak, and suggested I ask more relevant questions. He insisted that all possibilities are still being looked at, and that investigators don’t rule out Ukrainians carrying out the murder.

Still in that case, he and other police officials told me, they believe that the assassins would have been contracted, trained and provided with the bomb by Russian operatives, who then would have helped them disappear.

In recent months, authorities have acknowledged problems with the investigation. Prosecutor General Yuriy Lutsenko said mistakes were made. Speaking in parliament on May 24, he said, according to the Interfax-Ukraine news agency, national police missed “the most important” security camera footage—one of the videos obtained by the documentary journalists—early on in the investigation. “It’s a pity that this became known to the whole world, and not just to the investigation, but nevertheless these recordings are very important for the inquiry,” Lutsenko said, adding that the police recognized their error and were “trying to make up for lost time.”

Just the day before, Deputy Interior Minister Vadim Troyan was quoted as saying that when police received a video with footage of the suspects obtained by the SBU it had been destroyed. The SBU’s chief, Grytsak, countered on May 25, saying the video was fine when handed over, according to reports.

Such mistakes, coupled with a stalled investigation, make the prospect of securing justice a distant prospect. As Prytula said, “A murder becomes 10 times harder to solve so long after.”

Ukrainian authorities have made little progress in identifying—let alone catching—Sheremet’s killers. The investigation is fraught with infighting between members of the law enforcement agencies assigned to the case. Evidence has been overlooked and damaged. The few new leads have come not from authorities, but from investigative journalists. And some of the potential witnesses those journalists identified include people associated with or closely allied to the agencies tasked with solving case. This further raises concerns about the investigation’s credibility and objectivity.

From the beginning, Ukraine has claimed that Russia’s security services masterminded the assassination. But a greater amount of circumstantial evidence points to a Ukrainian trace, raising questions about why authorities are pushing the Russian narrative and whether they may be covering up evidence to protect someone powerful. If that is not the case, Sheremet’s family, friends and colleagues say, authorities should make public evidence that demonstrates a Russian hand in his killing.

Several of Sheremet’s colleagues added that the absence of information has created a chilling effect on free speech and spawned a greater distrust and suspicion of authorities. The brazen murder of such a prominent journalist makes it difficult for many to move on and return to even a semblance of normality.

Prytula has not yet returned to her job, and says she is working on “healing my soul, gathering the strength I need to continue.”

In Minsk, Sheremet’s mother, Lyudmila Sheremet, offered words of support through a trembling voice, reiterating something she told colleagues of her son at his funeral: “Make sure Pavel did not die in vain. Keep fighting.”