The EU and press freedom

“The European Union should…” Nearly every day this remark is on the lips of press freedom activists who blame the EU for not doing enough for press freedom. “The EU should call Hungary to order.” “The EU should slam Russia for its repression of the independent media.” “The EU should punish Ethiopia for jailing journalists and bloggers.” These expectations and, at times, exasperation are inevitable. The EU, with its 28 member states, describes itself as a democratic haven and the largest economy and trading group in the world. Brussels, home of the major EU institutions and host of the world’s third largest international press corps, has constantly proclaimed that its internal political order and foreign policy are based on human rights, rule of law, and democracy. So shouldn’t the EU be judged according to the yardstick by which it has chosen to measure others?

Consistency in its approach to the protection of press freedom is crucial if the EU wants to retain its authority. Yet some member states have criminal defamation laws, spy on journalists, and harass media covering protests; others, such as Hungary, have been allowed to backtrack on human rights responsibilities. When the EU deals with repressive nations outside the union, strong economic or strategic partners are less likely to be reprimanded than less important countries.

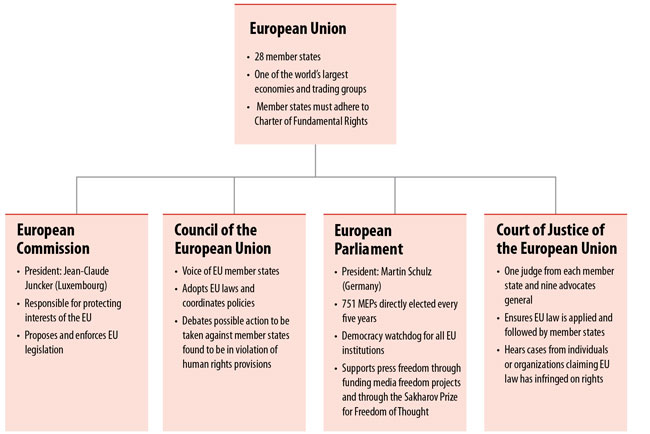

EU officials often react with irritation to such criticism, claiming it reflects ignorance of the EU institutional and legal system. They are not totally wrong. The EU’s most visible institutions—the European Commission, the Council, the European Parliament, and the Court of Justice—are not as powerful as Europhobes fear and Europhiles dream of, at least when it comes to fundamental rights. The structure of the EU is sensitive to the concerns of member states and was set up to not impinge on core sovereignty, national identity, and constitutional individuality.

Many EU officials believe that its press freedom record should exempt the EU from scrutiny. “Why are you wasting your time monitoring the EU record while journalists are murdered in Mexico and beheaded in Syria?” one official asked CPJ. Seen from those countries, the EU appears like a safe haven for the press: Murders of journalists are an exception. The killing of eight journalists in the January 2015 attack against satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo raised to 18 the number of journalists killed in direct relation to their work in the region between 1992 and September 2015, according to CPJ research. (Six of the 18 killings took place in a country not yet an EU member). At the time of writing, no journalist was in jail in a member state, according to CPJ’s annual prison census. Member states are frequently found at the top of most international press freedom rankings. However, the EU cannot be complacent. Its members do not have an immaculate record and “headwinds are blowing,” as Françoise Tulkens, chair of the Council of Europe’s committee of experts on protection of journalism and safety of journalists, and former vice president of the European Court of Human Rights, told CPJ. Democracies can backtrack, as Italy did under Silvio Berlusconi or Hungary under Viktor Orbán.

Inconsistency in policies said to be based in the defense of democracy and human rights is, at times, putting journalists at risk. For instance, member states are supposed to provide emergency visas to journalists under threat, but in May 2015 Sweden turned down a request from Bangladeshi blogger Ananta Bijoy Das over concerns that he would try to remain in the country. He was hacked to death a few days later in retaliation for his work.

In times of crisis, public opinion is volatile and security can be prioritized over liberty. Member states have been tempted to overreact in such circumstances, implementing counterterrorism regulations that risk muzzling the free press, CPJ found. Popular mistrust of the media also threatens to undermine their capacity to resist government regulation. “Many are skeptical of the very potential of the media in general to fulfill their function of informing citizens,” a 2013 European University Institute policy paper commissioned by the European Commission found. The Leveson Inquiry in the U.K., in the wake of the News of the World phone hacking scandal, showed how some politicians are tempted to tame the media under the cover of journalism ethics. The transformations and transitions within the media economy, the impact of the Internet, proliferation of social media, and the domination of a few mega-companies are also viewed with concern, especially by journalists’ associations. Many legacy media and public broadcasters have suffered substantial staff and budget reductions, which affect their capacity to act as watchdogs of national and European institutions, according to the 2015 publication European Media in Crisis: Values, Risks and Policies. And new media have not yet taken up the slack.

The risks are all the more serious since straying member states such as Hungary and Bulgaria have been only mildly reprimanded by the institutions supposed to protect press freedom under Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The Council, which represents the member states and is an essential EU decision-maker, for example, has a Working Party on Fundamental Rights, Citizens’ Rights and Free Movement of People, which is supposed to discuss responses to violations. But on politically tough issues it has been lacking. As the Human Rights and Democracy Network, a Brussels-based informal network of human rights organizations, found in August 2013, “Faced with systematic efforts by the Hungarian government to undermine the rule of law and human rights … the council has been silent.”

Although its statements sound high-minded, the council tends to adopt “the lowest common denominator on most press freedom-related issues,” Le Monde correspondent Jean-Pierre Stroobants told CPJ, expressing a view prevalent among members of the EU press corps with whom CPJ talked. Attached to national sovereignty, suspicious of what they view as Brussels’ uber-power, and often guilty of national practices that do not conform with the Charter of Fundamental Rights, many member states have fought to keep press freedom outside of direct EU purview.

This gap between the EU’s discourse and its practices partly explains the disappointment among those expecting a more principled and proactive press freedom policy. For advocates who consider press freedom a key pillar, the EU fails to bring into balance its values and policies. “I’d like the EU to be as imaginative on fundamental rights [as] it has been on austerity programs,” historian and columnist Rui Tavares, a former Portuguese Member of the European Parliament (MEP) and author of a critical European Parliament report on Hungary in 2013, said half-jokingly at a June 2015 conference in Brussels on illiberal democracies.

Legally, the crucial issue when it comes to press freedom is how much power the treaties on which the EU is founded confer to its institutions—in particular, its executive arm, the European Commission. EU institutions do not have much formal power in this field. The Charter of Fundamental Rights, which became binding after the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, applies only to member states when they are enforcing EU law. The clause allows these states to escape potential sanctions from Brussels since most of the issues raised by press freedom are not covered by specific EU legislation.

Politically, the press freedom discussion is clouded by disagreements on what the EU should be. A number of member states and some of the diverse political groups in the Parliament are loath to grant Brussels too much supranational power—not only because they fear finding themselves next in the EU’s line of fire if they transgress treaties but, more fundamentally, because they oppose what they describe as a power grab by Brussels bureaucrats. Asking the EU as an institution to do more in favor of press freedom collides with the debate on how much influence Brussels should have. In the current political context marked by the row over Greece’s austerity programs, the rise of nationalist and populist parties, and the prospect of a referendum in 2017 on the U.K.’s presence in the EU, the suggestion of providing more power to a “European super-state,” as Britain’s former Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher branded it in a 1988 speech, is not welcomed by a majority of edgy governments.

In such circumstances, media and press freedom policies will remain largely the preserve of member states, except when they touch the raw nerve of the EU: competition and trade.

But should EU press freedom policies be determined by such a minimalist approach? “How can the EU hope of convincing other governments, from Turkey to China, to improve their press freedom record if it is itself at fault?” Amnesty International Belgium Director Philippe Hensmans asked CPJ. The EU’s approach to violations by member states has opened it up to criticism from countries it seeks to reprimand, such as Russia. A report on human rights in Europe, commissioned by Russia, found that the EU “virtually ignore[s] the real state of affairs in the EU.” It added: “The governing bodies of the Union show indulgence, to say the least, towards violations of human rights by member states. For example … the investigation of undemocratic reforms in Hungary has been virtually soft-pedaled.”

“How can the EU hope of convincing other governments, from Turkey to China, to improve their press freedom record if it is itself at fault?”

– Philippe Hensmans, Amnesty International Belgium

Of the EU’s most visible institutions, the European Parliament has put press freedom on the agenda most often, even if “the active press freedom lobby in the [Parliament] is very small,” Portuguese Socialist MEP Ana Gomes told CPJ. It has done so through hearings, resolutions, missions, even its Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, whose laureates have included the Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje in 1993, Cuban blogger Guillermo Fariñas in 2010, and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat in 2011. The Parliament has also provided the commission with funding for pilot projects on media freedom.

But the European assembly is limited by its relative lack of power and by partisanship. “The system is dominated by the two largest groups, the center-right EPP [European People’s Party] and center-left S&D [Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats], and they will usually not oppose countries where their partner parties are in government,” Emilio De Capitani, former director of the Civil Liberties Committee unit, told CPJ.

The general defense of press freedom gathers quasi-universal support, but when a resolution puts a specific government or member party in a hot seat, clannish party loyalty pops up. In July 2013, a report authored by MEP Tavares that accused Hungary of failing to meet EU standards and asked for firm action was adopted with only 370 votes in favor, 240 against, and 82 abstentions, with the EPP, a group of Christian Democrats and center-right national parties, closing ranks behind its 14 MEPs from Hungary’s Fidesz. The vote followed the partisan pattern that, according to reports, protected Italy’s Conservative then-prime minister and media mogul, Silvio Berlusconi, against resolutions over his domination of Italy’s private and public broadcasting sector.

The European Commission, which initiates legislation, is viewed as the executive arm of the EU and some expect a lot from it. “It should provide the common narrative” and guard the EU against “member states’ backstabbing and petty squabbles,” said Internet freedom activist and former Swedish Pirate Party MEP Amelia Andersdotter at the May 2015 re:publica digital culture conference in Berlin. Commission officials diverge, however, when asked to describe press freedom prerogatives. Some can be assertive, like former Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding (now a Christian Democratic MEP from Luxembourg) who, in 2009, gave her backing to the European Charter on Freedom of the Press, a non-binding document against government interference signed by 48 editors-in-chief and journalists from 19 countries. But a top commission official, who asked not to be named, told CPJ, “We are more of a facilitator through support to various projects and through awareness-raising initiatives. We should not promise what the treaties tell us we cannot deliver.”

Within the commission, First Vice-President Frans Timmermans is in charge of the rule of law and fundamental freedoms, and must ensure that its decisions and initiatives comply with the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Practically, however, the European Commission Directorate General for Communications, Networks, Content and Technology (DG Connect) is the most directly concerned with the press. Its Converging Media and Content unit deals with media policies and has been on the front line, for instance, with Hungary over its media laws. It works closely with other directorates involved in press freedom, including the Directorate-General for Justice; the Directorate-General for Competition, which guards against unfair market policies; the Directorate-General for Neighborhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR), which negotiates with candidate countries; and the European External Action Service, the EU’s fledgling ministry of foreign affairs.

The Luxembourg-based Court of Justice has also assumed a more active role. Its judgments, such as the so-called right to be forgotten ruling, which allows people to request that links be deleted from search engines, are binding and have a direct impact on member states. “Press freedom groups, professional organizations, and media companies are increasingly keeping an eye on this institution,” European Federation of Journalists Director Renate Schroeder told CPJ.

Hidden by these mammoth institutions is the Vienna-based EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, which advises the EU on essential values in its actions, based on what the treaties say. In terms of press freedom, its impact has been marginal. The agency, its website states, has tackled issues such as privacy in the information society, but a number of observers told CPJ they would like it to play an enhanced role in monitoring press freedom in member states

Outside of the EU, other European intergovernmental organizations and institutions, such as the Strasbourg-based Council of Europe, the European Court of Human Rights, and the Vienna-based Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), are supposed to bolster its human rights and press freedom strategy. However, CPJ found that cooperation and outsourcing are not solutions and can even be a way for the EU to shirk its responsibilities.

“Fundamental rights should not be regarded as an afterthought, but rather as the essence of what the EU stands for.”

– First Vice-President Frans Timmermans at committee hearing

Although EU bodies are officially committed to protect press freedom, political will—or the lack thereof—is the key challenge. What has been achieved in the field of internal trade or competition policy, press freedom advocates told CPJ, should be the yardstick for respect of fundamental values and, in particular, press freedom. “Fundamental rights should not be regarded as an afterthought, but rather as the essence of what the EU stands for,” Timmermans said at a Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs committee hearing in Brussels in March 2015. Some press freedom groups and organizations, including the European Federation of Journalists and the Association of European Journalists, told CPJ that the apparently weak prerogatives of the EU in matters of press freedom and the fear of “more Europe” cannot be pretexts for passivity or complacency.

The challenges, however, are enormous. The discussion on EU competencies on press freedom is “an impenetrable jungle and I fear no one really has an overall grasp of all the issues,” European Journalism Centre Director Wilfried Rütten told CPJ. Despite being lumped together in the “EU” acronym, member states have a complex set of legal, cultural, and media traditions. On surveillance, for instance, U.K. public opinion backs the legitimacy of its Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) intelligence service, according to a 2013 YouGov poll, while the German public was reported to be more hostile, with one politician going as far as linking surveillance revelations to the Gestapo and Stasi eras.

However, if member states differ on key freedom of expression issues such as defamation, hate speech, and access to information, a common EU media identity is slowly emerging, which differentiates it from authoritarian states such as Russia and China—and also from its democratic ally, the U.S.

The U.S. is an active participant in EU media policy discussions, not only through government but also through its tech giants, lawyers’ offices, and non-governmental organizations that have set up shop in the Brussels beltway. It is therefore likely that some of the debates on freedom of expression in Europe will be influenced by U.S. views and policies on, for instance, encryption, privacy, and mass surveillance.

Even if they share fundamental values, media professionals and press freedom activists on both sides of the Atlantic do not always agree. “As opposed to the U.S.-American market liberal approach (‘freedom from…’) there seems to be wider support in Europe for a model that actively supports and regulates press freedom and media pluralism (‘freedom to…’),” writes Andrea Czepek in the introduction to the 2009 book Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe, which she co-authored. There are also differences in how the EU and U.S. define and repress hate speech. “The EU does not only condemn direct incitement to violence, as the U.S. does, but also incitement to racism and discrimination,” Debora Guidetti, program manager of the Open Society Initiative for Europe, told CPJ. “On this issue, U.S. and EU freedom of expression and anti-racist activists find it very difficult to understand each other and to agree upon a common course and discourse.”

Another dividing factor is privacy. “If Americans value freedom of speech as an inalienable right that sometimes must trump privacy, in Europe the right to privacy is so fundamental that all national laws must consider it,” Claude Moraes, U.K. Labor MEP and chair of the European Parliament Civil Liberties Committee, told Christian Science Monitor in January 2015.

In particular, U.S.-EU competition shapes the digital agenda. As Giovanni Gangemi, a research assistant at the European University Institute, wrote in a January 2013 essay for the Florence-based Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom: “The new operators emerging from the Internet economy are almost exclusively U.S.-based, while Europe struggles to establish new players that are able to compete with them.” The revelations by former U.S. National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden on spying in Europe, even if European intelligence agencies were exposed as being complicit, increased a feeling of vulnerability and dependence, which partly explains the commission’s “war,” as The Wall Street Journal described it, “against U.S. technology superpowers.”

On a cautionary note, these discussions are taking place during a decline in EU and U.S. international influence and the rise of authoritarian states such as China and Russia and brutal non-state actors such as the militant group Islamic State. “In an increasingly challenging global environment, the relevance of universal standards is questioned and the EU’s endeavor to promote them meets with growing resistance,” the EU wrote candidly in its 2015-19 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy. This report highlights the urgency of approaching press freedom globally and of forming a worldwide coalition if one aspires, as Columbia University President Lee Bollinger put it in a 2010 essay, to defend an “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open free press for a new century.”