When fighting erupted in Sudan on April 15 of last year, local journalists quickly ran into difficulties reporting on the conflict roiling their country. As the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – former allies who jointly seized power in a 2021 coup – engaged in street battles, journalists were assaulted, arrested, or even killed. Others found themselves stuck at home in cities and towns under siege or unable to report due to communications blackouts. Many journalists fled, resurrecting shuttered newsrooms abroad.

Yet one year into the war that has killed 14,000 people and displaced millions, journalists continue their struggle to cover its devastating impact.

Here are the top challenges to journalism in Sudan:

Journalists have been killed, injured, and harassed

At least two journalists have been killed in the war. Halima Idris Salim, a reporter for local independent online news outlet Sudan Bukra, was killed on October 10 when RSF soldiers ran her over with a vehicle while she was crossing the street on her way to report on conditions at a hospital in Umbada, a suburb of Omdurman. On March 1, Khalid Balal, media director at the Supreme Council for Media and Culture, a government regulatory body, and a member of the local trade union Sudanese Journalists Syndicate, was shot and killed by unidentified individuals at his home in El Fasher in North Darfur State. Two local journalists who spoke with CPJ on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal said that Balal was killed due to his long career in journalism. These were the first media killings CPJ has recorded in Sudan since 2006, when one journalist was murdered in retaliation for his coverage.

Other journalists have been injured. CPJ has documented multiple incidents of the RSF beating and harassing local journalists. The SAF also beat a journalist, Mohamed Othman, early in the war.

Journalists are being detained by the paramilitary

On April 15, 2023, the RSF raided and seized control of the state television headquarters in Omdurman, stopping the broadcast and trapping journalists and media workers inside for weeks. The RSF continued to use the building for military operations and as a detention facility for 11 months until March 12, when the SAF seized it in a significant advance against the RSF.

The RSF has detained other journalists through the course of the war, including at checkpoints and at military and civilian sites. Haitham Dafallah, editor-in-chief of local independent news website al-Maidan, was arrested by the RSF in January; as of mid-April, he and his brother Omar, who was arrested at the same time, remain in detention, according to the two local journalists. CPJ has not documented any journalist arrests at the hands of the SAF, though the SAF has detained many people, including at military and civilian sites.

Communications blackouts have impeded reporting

Telecommunications and internet services have been regularly interrupted over the past year, as fighting in major cities led to the destruction of mobile towers, repeated power outages, and fuel shortages. Between February and March, the country was in an almost total blackout, isolating Sudan from the rest of the world. Industry sources told Reuters that RSF was to blame for the widescale blackout, which RSF denied.

The interruptions have severely impeded the work of the press, who have had to access the internet through the Starlink satellite internet system founded by billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk. RSF rents devices at high prices, according to news reports, and one journalist, Ataf Mohamed, raised concerns in an interview with CPJ that the RSF is able to track journalists who use the internet via Starlink.

Foreign news channels covering the war have been banned

In April, the Sudanese government, which oversees the SAF, suspended the work of the Abu Dhabi-based Sky News Arabia news channel and Saudi Arabia’s state-owned channels Al Arabiya and Al Hadath, for allegedly failing to renew their licenses “uphold necessary standards of professionalism.” The move was criticized by the Sudanese Journalists Syndicate, a local trade union, which called it a “clear violation of freedom of expression and the freedom of the press.” Local journalists who spoke with CPJ called it an attempt to control the narrative of the media coverage of the war.

Journalists and media outlets have relocated

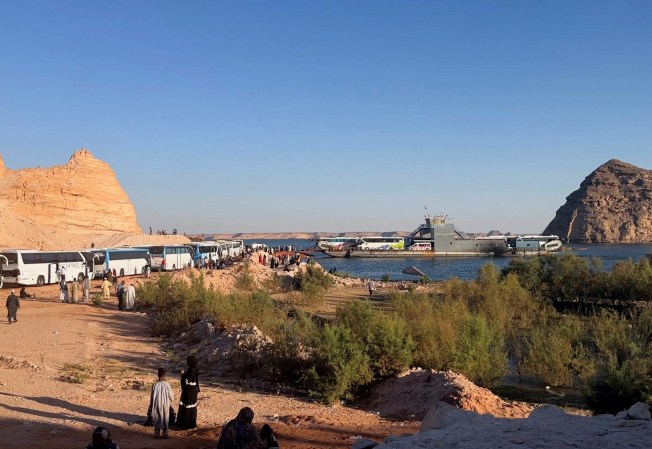

The Sudan war has displaced millions of people, including many journalists who fled hostile conditions. CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program, which provides support to frontline members of the press, has provided a window into the scale of the problem. At least 50 Sudanese journalists have applied for support, including those who have already fled the country and those trying to flee.

In addition, many news outlets have closed. Mohamed, a Sudanese editor who relocated his newsroom, Al-Sudani, to Egypt, estimated that close to two dozen print outlets have closed. He told CPJ that he relies on local journalists still in Sudan to provide updates using the internet from Starlink devices. In order to do that, the journalists have to go to RSF-controlled areas. “It is very dangerous for them to walk all that distance to send some information that can actually put them in danger,” he said.

Female journalists face gender-based violence

Since the war started, rights groups have documented a significant rise in conflict-related sexual violence against women and girls. Female journalists living in Sudan are not exempt from this danger.

Through its Journalist Assistance Program, CPJ has gathered testimonies from three local female journalists who spoke on the condition of anonymity, fearing reprisal. One said she was sexually assaulted by a member of the RSF, and two said that RSF members threatened them with sexual assault. With many women afraid of the stigma of reporting sexual violence, the number of journalists affected is likely higher.

Editor’s note: The number of journalists who have applied for assistance from CPJ has been corrected in the 10th paragraph.