Last year, when Raju Basnet was covering landgrabs in the Nepali city of Lalitpur, he knew he was playing with fire. His reports in the weekly Khojtalas alleged that powerful people, including government officials, were involved in the scheme and Basnet had already received multiple warnings to back off the story. Despite this, Basnet told me when we met in his small, makeshift office on the edge of Kathmandu, he never thought he would be arrested.

However, the day after he republished another outlet’s story on the same issue on his website, authorities detained Basnet for five days under the Electronic Transactions Act, a law purportedly designed to fight cybercrime, but which journalists say is used against reporters who share news or commentary on social media and websites.

“The environment is not journalist friendly,” Basnet said. “The situation is critical now.”

It was a sentiment shared by many of the journalists with whom I met in Kathmandu in October. While they acknowledged that generally the climate had improved since restrictions imposed under the monarchy and later the Maoist insurgency in the 1990s and early 2000s, in the past two years authorities have chipped away at the guarantee of “complete press freedom” included in the new 2015 constitution.

The K.P. Sharma Oli-led Communist Party of Nepal government has proposed several pieces of legislation that undermine the rights laid out in the constitution. Three proposed bills—the Media Council Bill, which recommends reforms to the semi-autonomous Press Council; the Advertisement Regulation Bill, which would make publishers accountable for content in advertisements; and the Information Technology Bill—were flagged as having a negative impact on the press.

Alongside new regulations, journalists spoke of pressure from officials and embassies to censor reporting, reduced access and transparency, and caution when reporting on privately owned companies who provide a large part of the news industry’s advertising revenue.

“With the new constitution we thought we had protection, but again we have to fight for democracy,” Guna Raj Luitel, editor of the Nepali-language daily Nagarik, told me.

The government has argued that it needs the bills to deal with misinformation and hate speech, and to improve the media environment. But the general sentiment among the press is that these proposals are motivated by a desire to prevent criticism and dissent. Journalists told me that if the proposals were passed in their present form, it would be the greatest threat to journalism in the country in years.

“The government is trying to propose several acts that infringe upon the constitution,” Prakash Rimal, editor of the English-language daily The Himalayan Times, told me. “They walk different paths, all of which lead to the curtailing of press freedom … [and] will only encourage censorship or self-censorship.”

In a phone interview in late December, Nepal’s minister of communication and information technology, Gokul Baskota, said that the proposals were “based on the constitution” and that any suggestion they could be used against journalists was “fake.” Baskota said, “We have never made anti-freedom press laws.” He added that some provisions were created to tackle crimes on social media, not mainstream media.

Press freedom restricted

The curtailment of press freedom began in 2017, when the Constituent Assembly passed the criminal code. When it came into effect the following year, CPJ voiced alarm over provisions that threatened public interest journalism. A government-formed committee suggested amendments but those proposals have not been honored, said Govinda Acharya, president of the Federation of Nepali Journalists. The local press freedom advocacy group was included in the committee.

While nearly every journalist I spoke with said that the Press Council was in need of reform, most said the bill they were concerned about most was the Media Council Bill. The proposal, introduced to Parliament in May, would amend the Press Council and bring it under further government control, as well as giving it power to impose fines for damaging a person’s reputation. The bill was brought forward without stakeholder input, circumventing the typical process in a move that caused outcry from journalists across the country. The Federation of Nepali Journalists submitted a number of proposed amendments, which the government has said will be discussed at the next National Assembly session.

When we spoke in December, Baskota said the pieces of legislation were still being debated and were following the democratic process

Under the Advertisement Regulation Bill, owners and publishers of media outlets could be held responsible for the contents of advertisements. The proposal includes stipulations for a fine of 10,000 Nepali rupees (US$90) and up to one year in jail for publishing content deemed offensive, false or confidential, according to the Himalayan Times.

Taranath Dahal, director of the local non-governmental organization Freedom Forum, said “I haven’t seen anything like this in a democratic country.” As of late December, the bill was with the National Assembly for approval, after the lower house endorsed it.

The Information Technology Bill would essentially repackage the existing Electronic Transactions Act, under which several journalists, including Basnet, were jailed. Nepal has faced major hacking incidents recently, so it does need a cyber-crime law, but not this kind, Babita Basnet, editor of the weekly Ghatana Ra Bichar, and no relation to Raju Basnet, told me over tea on a rainy afternoon.

In one case, comedian Pranesh Gautam was jailed for nine days in June under the Electronic Transactions Act , for critiquing a film on “Meme Nepal,” his YouTube channel.

“Before, even our brothers and sisters used to post jokes, criticizing the government. Now they’re not posting,” she said. “The fear is already there among the general people.”

Narayan Wagle, a senior journalist and former editor of the newspapers Kantipur and Nagarik, said, “If you allow police to interpret the act in their own way, the press will suffer.” Wagle added “The IT Bill will give police more authority, it equips them legally, making them more powerful so that the press behave.”

Numerous bills are being passed at provincial levels too, including the Radio Operation and Management Act of Province No. 1, which included provisions for imprisoning journalists for their work, before the Federation of Nepali Journalists lobbied successfully to have it removed, Acharya said.

Under pressure

Aside from restrictive legislation, editors in Kathmandu talked of how authorities and staff at some embassies applied pressure over stories that touched on transparency, development, or corruption. The editors said that while these phone calls were not overt threats, officials have called to ask questions about published reports and in some cases government supporters have called to criticize coverage.

Binod Dhungel, editor of the privately owned station Himalaya Television, said that on average, he gets calls once or twice a month. Babita Basnet said that she also gets calls, mostly from people complaining about their reporting on crime or corruption.

Rajesh KC, a cartoonist, said he also gets phone calls asking him why he is “anti-government.” He used to get similar calls during the king’s time and the Maoist conflict and said the motive was the same—the government does not want to be criticized.

Sanjeev Satgainya, a news editor at The Kathmandu Post, said that the government appeared to view any criticism as a ploy against it. “Anything critical is seen as destabilizing and a threat to democracy and the republican setup,” he said.

Anup Kaphle, editor of the English daily The Kathmandu Post, said staff in the Chinese embassy have called him and the publisher over coverage and that they were sensitive about stories on Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

Luitel, editor of Nagarik, said he had also received calls from staff at the Chinese embassy asking about the paper’s coverage on Hong Kong. Broadly speaking, Luitel said, the Nepali media shies away from issues considered sensitive in neighboring countries. “If you look at Kashmir or Tibet, it’s hardly touched,” he said. “Our government gets annoyed if we start reporting, we have been using wire stories.”

Nepal’s communication minister, Baskota denied there were attempts by the government to interfere with journalists.

China’s embassy in Nepal did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment.

There’s concern too about the influence of China and India on the Nepali government’s attitude toward the press, and the exporting of “Xi Jinping thought”—the Chinese president’s political philosophy that promotes the supremacy of the Communist Party. Deepak Adhikari, a freelance journalist, said the bills were a slide toward elected authoritarianism.

“[The government] praises Hun-Sen of Cambodia, they’re trying to be like China, when you hear things like that it’s worrying,” Kaphle, editor of The Kathmandu Post, said. “But they’ve also seen that it works … it’s working for Trump, it’s working for Erdoğan, it’s working for Modi.”

The journalists also talked about challenges in reporting on privately owned companies and businesses because of the risk of losing advertising revenue.

“We don’t do the digging that’s needed around the corporate world because they make such a big part of the advertisements and in Nepal the advertisement pie is really small,” Bhrikuti Rai, a reporter at The Kathmandu Post, said.

Luitel told me that if a news outlet reports critically on a company, the owners sometimes call the marketing department and withdraw advertising.

Ameet Dhakal, who runs Setopati, a news website funded entirely by advertising revenue, added, “I’m a little cautious not to kick too many doors at a time.”

Access denied

Several of the journalists said they have noticed restrictions in other areas: daily press briefings reduced to once a week, ministers less willing to speak to the media, and the Cabinet no longer regularly releasing its decisions on its website. In at least one case, authorities refused to renew a press pass.

Diya Chand, editor of Sanchar Kendra, a small Nepali news website that often reports on the banned Communist Party of Nepal, led by Netra Bikram Chand, told me officials refused to renew her press card after she wrote about an incident in which police allegedly killed a member of the party. Officials told her they had been told to deny her request because she was creating problems for the government. After working with the Federation of Nepali Journalists, she was finally able to get the pass renewed.

“If we compare it to the conflict-era or insurgency, the situation is much better, but it seems the government wants journalists to write what the government wants,” Bimal Gautam, editor of the investigative website Lokaantar, told me. “Calls from different sources or officials, these are minor things, but the government is also trying to muffle dissenting opinions and trying to teach the principles of journalism.”

The government feels they’ve been written badly about, Rimal said, and is trying to enforce what it refers to as responsible journalism.

That’s certainly the line that Kishore Shrestha, the politically-appointed chair of the Press Council, appeared to be pushing when we met to discuss the current press freedom climate in Nepal. He began by saying, “The situation is still vulnerable. We have been given too much press freedom.”

The Press Council introduced a new code of conduct recently, which includes provisions to allow the council to monitor journalists’ social media accounts and take action against posts that it deems are not respectful.

Shrestha said the code of conduct was necessary because Nepal’s media did not have “quality control” and that the media should be “responsible and professional.” Shrestha said he has a duty not just to defend press freedom, but also readers who may have been victimized by journalists and hate speech.

The chair, who also works for the weekly tabloid Jana Aastha, said that he agreed with some of the criticism of the Electronic Transactions Act and the Media Council Bill, and that he would push for amendments.

Mohna Ansari, a lawyer and member of the independent National Human Rights Commission Nepal, said the code of conduct ascribed by the press council was hypocritical. “In the name of controlling hate speech, you can’t curtail freedom of expression,” she said.

Kosmos Biswokarma, editor of the news website Kathmandu Press, went further, describing it as “bullshit.” “Democracy doesn’t work like that,” he said. “Who gets to decide what responsible journalism is?”

[Reporting from Kathmandu.]

Rojita Adhikari, a freelance journalist based in Kathmandu, contributed research and reporting to this piece.

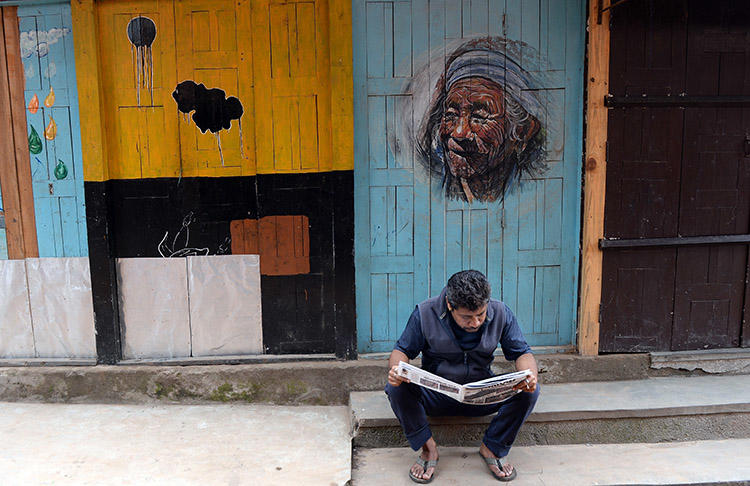

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This post has been updated to remove a photo that was published with incorrect caption information. The seventeenth and twenty second paragraphs were updated to clarify comments from Babita Basnet]