Adding forces or shirking responsibilities? The EU and intergovernmental bodies

When it comes to defending press freedom, the EU should be able to count on the support of other European institutions that share its values. The collaboration and interaction between the EU and these bodies should offer greater protection to journalists, but complex working arrangements and clashes in responsibility are diminishing what could be a powerful relationship. The EU has also been criticized for what is seen as its outsourcing of core responsibilities to institutions that count repressive countries among their members and have little power to implement decisions.

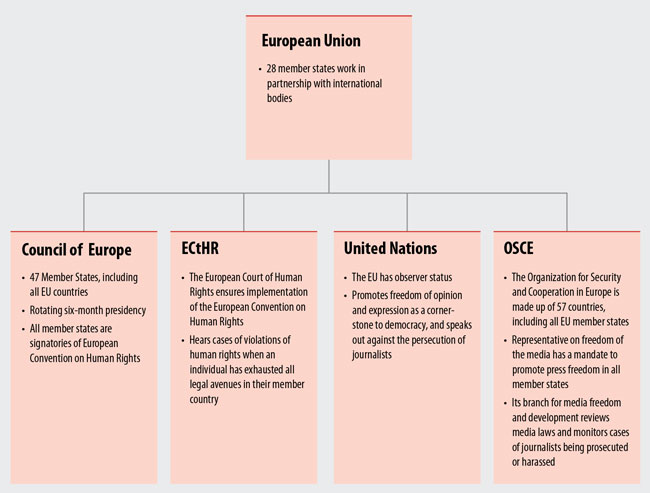

EU member states belong to the Council of Europe, which has a freedom of expression mandate; are party to the European Convention on Human Rights; and are subject to the European Court of Human Rights, which acts as the final recourse for journalists who have exhausted all legal avenues when challenging national court judgments. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) is also a participant in the EU’s press freedom debates and its representatives on freedom of the media have been particularly vocal in highlighting failings in member states. But its power to discipline straying countries has been limited.

The Council of Europe has made numerous resolutions and recommendations on press freedom, from the decriminalization of defamation to Internet freedom, that “have mostly been impeccable,” Giovanni Melogli, EU affairs director of the International Alliance of Journalists, told CPJ. Press freedom is regularly on the agenda of its Parliamentary Assembly meetings, its commissioner for human rights issues regular critical reports and comments on press freedom, and it has tried to draw attention to attacks on the press through the Platform to Protect Journalism and Promote Safety of Journalists, which is made up of press freedom groups. But the Council of Europe includes members whose values contradict the EU’s founding principles. Russia, for instance, has consistently attacked press freedom through repressive laws and failure to prosecute violence, and Azerbaijan continued its crackdown on dissident journalists while chair of the Committee of Ministers in 2014.

Aside from suspending a member, the Council of Europe has no way to implement decisions or make members accountable. At times, the bodies that make it up work at cross purposes too. In April 2014, for instance, the Parliamentary Assembly suspended Russia’s voting rights over what the EU ruled was the illegal annexation of Crimea—a move that has all but eradicated the independent press and broadcasters in the Ukrainian region, CPJ has found. But Russia was still able to participate in the more crucial Committee of Ministers.

A 2007 EU and Council of Europe memorandum that covered freedom of expression and information “clearly states that the Council of Europe will remain the benchmark for human rights, the rule of law, and democracy in Europe,” Humbert de Biolley, deputy head of the Council of Europe office in Brussels, told CPJ. The EU is involved in council committees such as the media and information society division, and its cooperation priorities with the Council of Europe for 2014-15 specifically refers to press freedom in relation to Azerbaijan, Russia, and Turkey. The focus makes sense: CPJ has documented how journalists in those countries have been put under increasing pressure through the threat of imprisonment, legal action, and harassment from authorities.

Officially Brussels and Strasbourg extol their cooperation, but the process can be “frustratingly complex,” a top Strasbourg council official, who requested anonymity, told CPJ. “The uncertainty on who is in charge in the EU can lead to canceling the work of various months because EU lawyers have suddenly judged that it did not conform to EU law. The European External Action Service for instance takes charge when the Council of Europe discusses the human rights aspect of the media, but the commission leads when the council addresses trans-border TV directives.”

A number of EU officials and observers are critical of what they consider to be the outsourcing of key constitutional issues, such as democratic governance or press freedom, to the Council of Europe. For those advocating for a more autonomous EU, the referral to the Council’s legal advisory board, the Venice Commission, over Hungary merely highlighted the lack of will of the EU to assume responsibility. This mismatch between the Council of Europe prerogatives and EU power does not serve press freedom well, they say. “The vital contribution played by the Council of Europe institutions in promoting human rights in EU countries should be seen as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, stronger EU action,” the Human Rights and Democracy Network wrote in August 2013.

“True, it is not an ideal world,” Tulkens, chair of the Council of Europe’s committee of experts on protection of journalism and safety of journalists, told CPJ. “But this is the world we are in. The EU cannot pretend to start from scratch. An enormous amount of work on press freedom has been done in Strasbourg. Of course the Council of Europe has no power of coercion and we know that the respect of human rights depends on binding rules. But in a field where progress takes a long time, you cannot minimize the corpus that has been developed over the years by the council.”

Press freedom advocates are also keen to protect and promote the European Convention on Human Rights and the role of the European Court of Human Rights. And they view any idea of competition with the Court of Justice of the European Union with concern. The way Article 10 of the convention has been applied by the Court of Human Rights and the Council of Europe “helped to upgrade and improve the level of freedom of expression and media freedom” in the EU, Dirk Voorhoof, professor of law at Ghent University in Belgium and an expert of Columbia University’s Global Freedom of Expression and Information project, wrote in a March 2015 presentation at Columbia University. Whistleblowing, access to documents, and protection of journalists’ sources were among the areas influenced by it, he said.

Tulkens, who is a former vice president of the European Court of Human Rights, warned that although “the court’s case law is still keeping high standards of freedom of expression and protection of journalists” … “headwinds are blowing against human rights in general and the court is not immune.” Despite having the tools to address press freedom violations, the court encounters difficulties in executing its judgments in a number of countries, as CPJ has documented in reports on Russia and Turkey. Tulkens added, “Freedom of expression is particularly sensitive to those winds which, actually, do not come only from the usual suspects, like Russia or Azerbaijan, but also from democracies where competing values like the right to reputation enter in conflict with freedom of expression. The court also ventures into dubious discussions on, for instance, ‘giving information in good faith,’ which is an issue for ethics councils and not for a court of law.”

According to the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, the EU was expected to adhere to the European Convention on Human Rights, but in December 2014 the Court of Justice ruled against the draft agreement, judging it incompatible with EU law. Tulkens described the decision to CPJ as “a catastrophe and a betrayal.”

“The EU’s accession to the ECHR [European Convention on Human Rights] would have submitted EU legislation and actions to the control of the European Court of Human Rights, an autonomous third party,” she said. Steve Peers, an EU law professor at the University of Essex in the U.K., added in a blog: “For all of us who support human rights protection, it is an unmitigated disaster.”

The tussle between the two European legal systems might take some time to work out. Meanwhile, some freedom of expression lawyers and activists told CPJ that such confusion risks playing into the hands of those governments, particularly non-EU members such as Russia, who want to reduce the powers of the European Court of Human Rights. Such an outcome would be at the expense of journalists who have consistently relied on the court to admonish their governments, overturn convictions, and uphold the commitment to press freedom. As a Belgian diplomat, who asked not to be named, told CPJ: “The protection and promotion of freedom of expression should trump a battle of turf and egos between two European institutions.”