One year ago Raza Rumi, a TV anchor and widely-respected analyst in Pakistan, narrowly escaped death when gunmen opened fire on his car in an attack that killed his driver, Mustafa. When I wrote about the March 28 attack, the fourth on the Express Group in eight months that had left four people dead, I highlighted the lack of a police investigation.

I went on to repeat a recommendation the Committee to Protect Journalists has made many times:

First and foremost, Friday’s attack on Rumi and his driver were crimes: murder and attempted murder. They must be investigated as such. It does not require a special commission, as came after the killing of Saleem Shazhad in 2011, or Hayatullah Khan in 2006, or after the sadistic attack on Umar Cheema in 2010. Practice has shown that those commissions achieve little or nothing, and the perpetrators go unprosecuted.

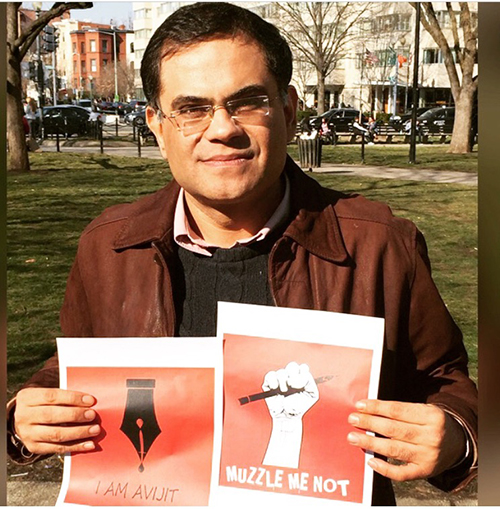

It’s not like the government took my advice, but there was no special commission named to look into the attack on Rumi and his driver. The police did investigate and there has been some movement, but little conclusive. In the past week, Rumi and I have been communicating about last year’s events. He moved to the U.S. soon after the attack, stringing together fellowships and think tank appointments, writing for papers in Pakistan and online, but no longer hosting his TV show. He filled me in on the status of the case:

Police in Lahore have arrested six individuals, which the authorities allege murdered my driver and tried to kill me. Authorities reported that the six suspects confessed, and provided a statement that they are members of the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi [a splinter terrorist group that has been around since the mid-1990s]. They said they were following the orders of Malik Ishaq, the leader of LeJ, when they attempted to assassinate me. The mastermind of this group is still at large and reportedly in Dubai. My guard Anwar and the family of my slain driver, Mustafa, told me that they have been getting threats from LeJ operatives since the attack. They have been warned by these operatives that they should not pursue this case; otherwise they will be harmed. My family’s driver also received threats. Malik Ishaq has not been charged. I do not believe the government of Pakistan can protect me from Ishaq, the LeJ, and the Taliban.

Rumi says he still receives threats. “After I criticized the violent ideologies of extremist groups, two different Twitter users responded, threatening that a fatwa would soon be issued calling for my death,” he told me, citing just one example of a response to tweets he had posted. “Near the end of July, when I highlighted 10 problems with current day Pakistan, including its laws that discriminate against religious minorities, I received the following message: ‘My sources telling me they’ll reply of] each tweet with bullet, 10 tweets so far and 10 bullets.’ “

For now, Rumi plans to stay in the U.S. “I am terrified of what might happen if I return to Pakistan,” he told me.

Last year was a bad one for the press in Pakistan, with three journalists killed directly for their work and three media workers shot dead in one attack, according to CPJ research. In March, Rumi was attacked. In April Geo TV talk show host Hamid Mir was gunned down, but survived taking six rounds, with two still in his body, he told CPJ. This year is better, with no deaths so far. Pakistan Rangers in Karachi were reported to have nabbed Faisal Mota, one of the killers of Geo TV reporter Wali Khan Babar, who was shot dead in January 2011, when they swept through the headquarters of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement headquarters in March, part of a broader effort to quieten the opposition party. Mota had been sentenced in absentia to death by the anti-terrorism court that heard the Babar case in 2014, according to CPJ research.

And, CPJ’s 2007 International Press Freedom Award winner Mazhar Abbas told me there has been movement in the low profile case of Shan Dahar, a provincial reporter for Abb Takk TV, who was shot dead on January 1, 2014, apparently because he was pursuing a story about the illegal resale of prescription drugs in his hometown of Larkana. Abbas told me Sindh Information Minister Sharjeel Inam Memon has promised to move the case to Karachi, where it can be pursued without interference from local powerbrokers, a request made by Dahar’s family.

All that sounds good, but does not reflect the fuller reality. After the attack on Mir last year, Geo TV came under sustained attack from security services. CPJ documented its attempts to drive the channel off air through broadcast regulations and legal attacks. While live on Geo TV, Mir’s brother accused the country’s intelligence services of being behind the assassination attempt. In an apparent response to the official anger, advertisers started to move to other stations. During a visit to Pakistan in February, it was clear to me that Geo has survived, but is much diminished. Competing media, broadcast and print, were also bombed, shot, and threatened CPJ research shows. And these outlets saw what happens when you take on the government, dialed back their coverage, and sought to grab as much of Geo’s audience as possible.

In January there was a closed meeting with government officials and journalists from editors’ groups, the alliance of broadcasters, and newspaper owners, about how to cover the political violence wracking the country. “There was an agreement that no news should be blacked out, but there should be a code as how to present news about terrorism,” Abbas told me. “As far as legislation is concerned there are speculative reports about an amendment to the laws controlling the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority law to allow government to blackout news items, which they consider against the ‘national interest.'”

- For a list of commitments made to CPJ by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in March 2014, click here.