On February 11, 2011, as journalists were documenting the raucous celebration in Cairo’s Tahrir Square following the fall of Hosni Mubarak, the story took a sudden and unexpected turn. CBS 60 Minutes correspondent Lara Logan, who was reporting from the square, was violently separated from her crew and security detail by a mob of men. They tore her clothes from her body, beat her, and brutalized her while repeatedly raping her with their hands. Logan was saved by a group of Egyptian women who berated her attackers until a group of Egyptian army officers arrived and took her to safety.

Details of the attack on Logan were sketchy, and in the immediate aftermath there was a good deal of confusion and some predictable but unfortunate criticism as well. Some raised questions about Logan’s judgment in reporting from Tahrir Square at a volatile moment. Others questioned the appropriateness of her dress.

But there was a more serious concern among leading female journalists with whom I was in touch at the time. They worried that the intensive coverage of Logan’s attack could affect them professionally. These journalists had throughout their careers overcome discrimination and resistance from editors and managers in taking on the most dangerous and difficult assignments. They worried that a focus on the risk of sexualized violence would reinforce resistance from editors. The concern was not entirely academic. In November 2011, after a sexualized attack on a French journalist, Caroline Sinz, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) issued a statement noting, “This is at least the third time a woman reporter has been sexually assaulted since the start of the Egyptian revolution. Media should take this into account and for the time being stop sending female journalists to cover the situation in Egypt.”

The response was immediate and fierce. Writing in theGuardian, journalist and documentary filmmaker Jenny Kleeman noted, “The threat to women is undeniable and should not be underestimated. But then again, so is the threat to men. In 2011 so far, 58 journalists have been killed on the job, only two of them female. Yet I see no statement from RSF urging men not to be sent into the field.” In response to the outcry, RSF modified its statement, which today reads, “It is more dangerous for a woman than a man to cover the demonstrations in Tahrir Square. That is the reality and the media must face it.”

At CPJ, we faced criticism of our own. Many friends of the organization pointed out that we had not done enough to document sexualized violence and that we did not collect the kind of comprehensive data we have on killed and imprisoned journalists. Of course, it is more difficult to document sexualized violence because of its stigmatizing nature, but our then-senior editor, Lauren Wolfe, demonstrated that it could be done through persistence and determination.

During the three months following the attack on Logan, Wolfe interviewed dozens of reporters who described their experience with sexualized violence, many speaking publicly for the first time. These incidents ranged from rape to groping and harassment during demonstrations. Victims told Wolfe that they had not spoken out for a variety of reasons including societal norms, a belief that authorities would not pursue an investigation, and most distressingly, a concern that they would face discrimination in their own newsrooms.

The CPJ report was dubbed “The Silencing Crime,”a reference to the way that sexualized violence both stigmatizes and censors. “The Silencing Crime” garnered intensive media coverage, and was the first in a series of reports, including a combined effort from The International News and Safety Institute (INSI) and the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF), which in March 2014 published “Violence and Harassment Against Women in the News Media: A Global Picture.”

On May 1, 2011, Logan was interviewed on “60 Minutes” by her colleague Scott Pelley and described her experience in unflinching detail. When asked why she was speaking out, Logan said she wanted to “break the silence” noting that women “never complain about incidents of sexual violence because you don’t want someone to say, ‘Well, women shouldn’t be out there.’ But I think there are a lot of women who experience these kinds of things as journalists and they don’t want it to stop their job because they do it for the same reasons as me–they are committed to what they do. They are not adrenaline junkies, you know, they’re not glory hounds, they do it because they believe in being journalists.”

* * *

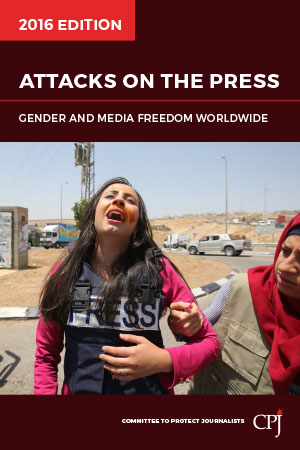

Five years later, the landscape looks very different. It’s better in some ways, but worse in others. This year, Attacks on the Press looks not only at sexualized violence and online harassment but also more broadly at the intersection of gender and press freedom from a variety of perspectives.

Colombian journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima provides a harrowing and moving account of being raped 16 years ago by men who sought to punish her for her reporting on arms trafficking and to terrorize others who might pursue similar stories. Bedoya would not be silenced. Not only did she continue to speak out, her courage rallied the nation of Colombia to confront the issue of sexualized violence. Today, by presidential decree, the date of Bedoya’s abduction, May 25, is marked with marches and rallies as the National Day for the Dignity of Women Victims of Sexual Violence. “Words can indeed change the world,” notes Bedoya in her essay.

Words can also do tremendous harm, as we see in a series of essays about the online harassment of women journalists, including the phenomenon of Internet trolling–the systematic targeting of online posters by hostile individuals, which in many cases include threats of physical harm. In her fascinating reported piece, Elisabeth Witchel explores the issue from the perspective of the trolls. Who are these people, and why do they do what they do? The answers are surprising.

A piece by Michelle Ferrier, a former columnist for Florida’s Daytona Beach News-Journal, describes the emotional toll inflicted by relentless denigration and verbal assault. In Ferrier’s case, most of the attacks came in the form of letters and not tweets, and focused more on her race than her gender. But Ferrier captures the feelings of fear, helplessness, and isolation of those experiencing unceasing insults. “Unless it has happened to you, it is hard to imagine what this kind of stalking feels like,” she writes. “Trust me. You don’t want to know.”

Other essays examine the challenge and consequences of gender-based discrimination in a variety of societies. Yaqiu Wang describes how even as more and more women in China enter the field of journalism, their opportunities for advancement remain limited. Preethi Nallu looks at women journalists reporting on post-Qaddafi Libya, which has become less overtly repressive but more polarized and violent. Some female journalists have gone into exile due to their high visibility. Jessica Jerreat examines the varying challenges faced by transgender journalists overcoming discrimination in newsrooms in the U.K. and staying safe while reporting in Uganda. Jake Naughton explores how gay men and women–and even reporters who cover their issues –are subject to harassment in Kenya.

Meanwhile, Alessandra Masi and Erin Banco describe the advantages that female journalists bring to the coverage of complex stories, reminding us of what is lost when their voices are shut out. Masi, a journalist based in Beirut, uses social media to report on the Islamic State, finding that her gender gives her new insights into their recruitment strategies and the kind of society they are seeking to create. Banco, who reported from the Middle East region, reveals how she gained experience as a conflict reporter but had to earn the respect of her male sources and colleagues. At the same time, she found her gender to be an advantage. “As a woman, I am able to gain access to the women and girls that are often asked to sit in a side room while I interview their father, brother, or uncle,” she writes. “As a woman, I can sit with a mother and her children alone without her husband and speak to her candidly.” Sometimes, notes Kathleen Carroll in her essay, a woman may also be granted special access when it comes to comforting journalists who suffer attacks.

There are plenty of inspiring stories, although sometimes you have to look to find them. Arzu Geybullayeva describes how her friend, Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova, has courageously defied all efforts to silence her, standing up to smear campaigns, character assassination and, ultimately, a bogus prosecution and trial that resulted in her being sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison. Kerry Paterson describes how journalists are helping bring justice to victims of sexual violence–sometimes at the hands of peacekeepers–in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic. And María Salazar-Ferro profiles four courageous women who have led the fight for justice for journalists who have gone missing or been imprisoned or killed.

* * *

The essays in this volume challenge the various ways in which gender affects what we know about the world, and in particular the challenges women face in all societies to bring us the news. A number of other essays tackle the difficult question of what can be done.

CPJ’s advocacy director, Courtney Radsch, considers the ways journalists are attempting to combat gender-based online abuse and the debate over online anonymity. Karen Coates looks at some of the specialized safety training being provided to female journalists. Dunja Mijatović, the special rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the OSCE, outlines a series of practical and concrete steps that policymakers can take to combat online harassment.

These are all important measures that have the potential to improve the lives of journalists of any gender, and particularly women. But given the scope of the challenges–sexualized violence, harassment, discrimination–they seem distinctly unsatisfying. Clearly, vital voices are being suppressed and as a result, some of the information we need to make sense of a complex world is missing.

This is terribly distressing until one considers the extent to which the open discussion of the issue of gender represents progress. Only a few years ago, when Lauren Wolfe was researching her report for CPJ, she found so many journalists who had never talked about their experiences. Today, the environment has begun to change. As this volume makes clear, victims of sexualized violence–mostly women, but men as well–are speaking out. By doing so, they are helping reduce the stigma, making it easier for other victims to discuss their experiences. This, in turn, helps forge responses.

As more journalists speak out about these hidden abuses, CPJ is better able to document the violations. This means more data that will help us understand the nature and scope of the problem. In 2016, CPJ will make a more concerted effort to document incidents of sexualized violence and tag them on our website. We will also be speaking out more, using this book to organize a series of events and discussions.

Sexualized violence is different. At its most extreme, it is an almost incomprehensible horror, as Jineth Bedoya Lima’s account makes clear. It can never be normalized or accepted. But journalists must confront the risk in order to do their work. Editors, managers, colleagues and press freedom advocates must honor and support their decisions, seeking to mitigate the risk while recognizing it can never be eliminated. The reality of sexualized violence–not to mention the other challenges that women face in bringing us the news–should never be used to limit opportunities. Though solutions are hard to come by, talking openly is an important first step. We hope this book makes a contribution to that difficult process.

Joel Simon is the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. He has written widely on media issues, contributing to Slate, Columbia Journalism Review, The New York Review of Books, World Policy Journal, Asahi Shimbun, and The Times of India. His book, The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom, was published in November 2014.