By Jennifer Dunham/CPJ Deputy Editorial Director

Published January 24, 2023

Key Takeaways | Methodology | 2022 Killed Data | Interactive Map | Video

The year 2022 was deadly for members of the press. At least 67 journalists and media workers were killed during the year–the highest number since 2018 and an almost 50% increase from 2021, the Committee to Protect Journalists found. The rise was driven by a high number of journalist deaths covering the Ukraine war and a sharp rise in killings in Latin America.

(Editor’s note: Since publication of this report, CPJ documented the work-related killings of two additional journalists, one in Haiti and one in Latin America, bringing the total number of journalists killed in 2022 to 69. Please refer to our database for our most current information.)

CPJ has confirmed that at least 41 journalists and media workers were killed in direct connection with their work, and is investigating the motives for the killings of 26 others to determine whether they were work-related.

More than half of the 67 killings occurred in just three countries–Ukraine (15), Mexico (13), and Haiti (7), the highest yearly numbers CPJ has ever recorded for these countries.

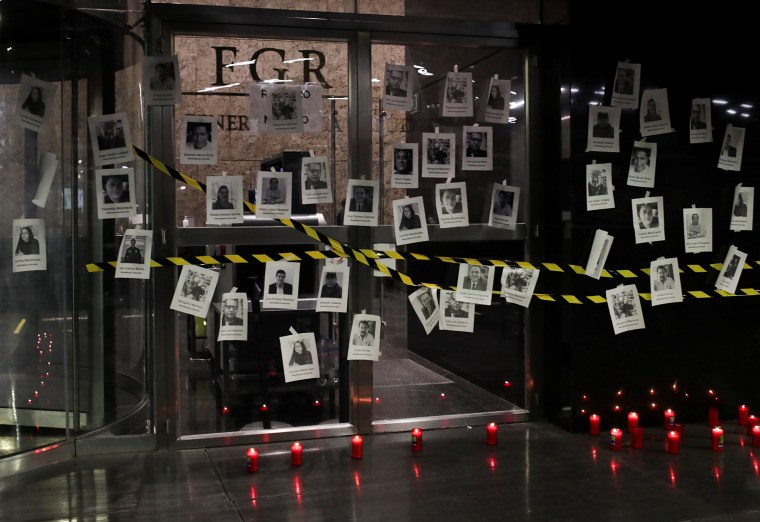

In Mexico and Haiti, reporters were the targets of brutal murders for their work, and the vast majority of perpetrators have not been held to account. Mexico continues to feature on CPJ’s Global Impunity Index, which highlights countries where the killers of journalists get away with murder.

Others who lost their lives during the year covered a range of beats: crime and corruption in Colombia; political unrest in Chad, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and Myanmar; the environment in Brazil; and local politics in Turkey and the United States. Their deaths underline the extent of threats faced by the press around the world, including in countries with democratically elected governments.

CPJ tracks three types of journalists’ deaths in relation to their work: targeted murders in reprisal for reporting–by far the largest category; deaths in combat or crossfire; and deaths on other dangerous assignments. CPJ also tracks the killings of media support workers, such as translators, drivers, and security guards; there was one such killing in 2022, in Kazakhstan.

Here are five takeaways from CPJ’s research on journalist killings in 2022:

Journalists covering the Ukraine war face enormous risk

At least 15 journalists were killed in Ukraine in 2022 following Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country on February 24. CPJ has confirmed that 13 of those were killed while engaged in newsgathering and reporting, and is investigating whether two others killed during the conflict lost their lives because of their media work.

Most died in the early stages of the war, and CPJ has not documented any work-related journalist killings in Ukraine since that of French cameraman Frédéric Leclerc-Imhoff in late May. However, the situation on the ground remains perilous: members of the press are frequently injured by shelling while covering the conflict, and some report that they have been targeted by Russian forces.

Latin America was the deadliest region to practice journalism

CPJ documented 30 journalists killed in Latin America in 2022, nearly half of the global total–a reflection of the outsize risk journalists in the region face while covering topics such as crime, corruption, gang violence, and the environment. At least 12 journalists were killed in direct relation to their work in Latin America, and CPJ is continuing to investigate the motive in 18 other deaths.

In Mexico, CPJ documented a total of 13 journalists killed, the highest-ever number in a single year. In three of those cases, journalists were murdered in retaliation for their reporting on crime and politics, and had received threats prior to their deaths. CPJ is investigating the motives for the 10 other killings, but in a country characterized by violence and impunity, it is notoriously difficult to confirm whether journalists were killed because of their work.

In Haiti, journalists covering gang violence and the political crisis and civil unrest sparked by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021 have faced an alarming upsurge in violent attacks. In 2022, at least five journalists were killed in relation to the work, and CPJ is investigating the motive in two other deaths. In two of those cases, the journalists were killed by the police.

CPJ also documented work-related killings of four journalists in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia, and is still investigating the motive in the deaths of six reporters in Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Paraguay.

Protection mechanisms fall short

In Mexico, there are several laws and entities that deal specifically with journalist protection, including state and federal protection mechanisms. However, these have proven ineffective in keeping journalists safe. Maria Guadalupe Lourdes Maldonado López, a veteran broadcast journalist who was shot dead in her car in Tijuana, Mexico, in January 2022, was enrolled in Baja California state mechanism at the time.

Two others–Alfonso Margarito Martínez Esquivel and Armando Linares López–were in the process of being incorporated into Mexico’s federal protection mechanism when they were murdered.

In Colombia in October, two men fatally shot journalist Rafael Emiro Moreno Garavito while he was at the fast-food restaurant he owned. Moreno, the director of independent news outlet Voces De Córdoba, had been threatened for years for his reporting on political corruption and drug-trafficking groups. The Colombian government’s National Protection Unit had assigned a bodyguard to protect Moreno and gave him a protective vest and an early-warning panic button. However, on the day he was killed, Moreno told his bodyguard that he could take the rest of the day off because he did not believe protection was necessary while working at his restaurant.

Shireen Abu Akleh’s murder spotlights Israeli impunity

In May 2022, Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was shot and killed while she reported on an Israeli military raid in the Palestinian West Bank city of Jenin. Eyewitnesses and multiple investigations concluded that an Israeli soldier fired the bullet that killed the veteran Al-Jazeera reporter, and a U.S. State Department probe found that gunfire from Israel Defense Forces’ positions was “likely responsible” for Abu Akleh’s death, but “found no reason to believe that this was intentional.” The Israeli government to date has failed to pursue a transparent investigation or take steps to bring those responsible to justice. CPJ has welcomed the November announcement by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation that it planned to open an investigation into Abu Akleh’s killing.

Abu Akleh’s murder was the latest example of Israeli impunity for crimes against the press. It came one year after Israeli forces bombed several buildings in the Gaza Strip housing media offices, including those of The Associated Press and Al-Jazeera. The Israeli government has not responded to CPJ’s request to provide evidence for Israel’s claims that Hamas militants were using the building for military purposes and to reaffirm the rights of journalists in Gaza to work freely and safely. In 2018, at least two other Palestinian journalists–Yaser Murtaja and Ahmed Abu Hussein–were shot and killed while covering demonstrations in the Gaza Strip; a U.N. commission of inquiry later found that Israeli snipers “intentionally” shot the two journalists. Israeli authorities have not clarified what investigations, if any, they undertook or whether anyone was brought to justice for the journalists’ murders.

Local reporters covering politics, crime, and corruption are frequent targets

Of the 19 journalists murdered in retaliation for their work in 2022, 18 were locals covering sensitive topics such as politics, crime, or corruption in their home countries.

All four of the murders in the Philippines were of radio journalists covering local politics, highlighting the dangers faced by the press in the country even as it transitioned to the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in June. In one particularly brazen case that sparked outrage and protests among journalists in the Philippines, radio commentator Percival Mabasa was gunned down in October; police later alleged that the Bureau of Corrections chief and another prison official had ordered Mabasa’s murder in retaliation for the reporter’s airing of corruption allegations.

The year also saw the first work-related murder of a U.S. reporter since a gunman shot and killed five employees at the Capital Gazette newspaper in Annapolis, Maryland, in 2018. In September 2022, Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Jeff German, who covered politics, crime, and corruption, was fatally stabbed by a local official who had lost a reelection bid after German’s reporting about alleged mismanagement in his office. The official was arrested shortly after the attack and is currently facing murder charges.

Another reporter on corruption, Pakistani journalist Arshad Sharif, was also killed in 2022. Sharif, a former TV anchor who had criticized corruption in Pakistan, was shot dead by Kenyan police outside the country’s capital Nairobi in October. Pakistani investigators have said his killing was a “planned targeted assassination” rather than a case of mistaken identity as claimed by the Kenyan police. No one has been charged so far and CPJ is continuing to investigate whether the journalist was killed for his work.

Methodology

CPJ began compiling detailed records on all journalist deaths in 1992. CPJ staff members independently investigate and verify the circumstances behind each death. CPJ considers a case work-related only when its staff is reasonably certain that a journalist was killed in direct reprisal for his or her work; in combat-related crossfire; or while carrying out a dangerous assignment such as covering a protest that turns violent.

If the motives in a killing are unclear, but it is possible that a journalist died in relation to his or her work, CPJ classifies the case as “unconfirmed” and continues to investigate.

CPJ’s list does not include journalists who died of illness or were killed in car or plane accidents unless the crash was caused by hostile action. Other press organizations using different criteria cite different numbers of deaths.

CPJ’s database of journalists killed in 2022 includes capsule reports on each victim and filters for examining trends in the data. CPJ maintains a database of all journalists killed since 1992 and those who have gone missing or are imprisoned for their work.

Learn more about CPJ’s 2022 data on killed and imprisoned journalists from our interactive map.

Jennifer Dunham is CPJ’s deputy editorial director. Prior to joining CPJ, she was research director for Freedom House’s Freedom in the World and Freedom of the Press reports.