Pursuit of truth comes at heavy price for India’s Right to Information activists

By Aayush Soni

Ever since India’s Right to Information Act was passed in 2005, it has empowered citizens to challenge the opaqueness of state and federal government decision-making. Activists across India have used the act to expose wrongdoing such as illegal mining, and to act as a watchdog on political processes. In many cases, the details these activists unearth are later reported on by the mainstream media.

But this effort to bring about transparency and expose wrongdoing can come at a heavy price. Between March 2007 and April 1, 2016, at least 58 activists—those who regularly file requests—have been killed, and more than 250 have been harassed or assaulted, according to the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information. The New Delhi-based advocacy group, which campaigns to protect and promote the law, uses news reports to track attacks and harassment of activists.

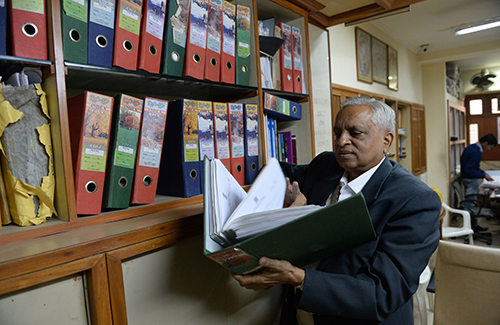

Those in rural areas and small towns are more vulnerable to attack than those who live in cities such as Delhi and Mumbai, Subhash Agrawal, a Delhi-based activist with more than 6,000 information requests to his name, said. When the activists are attempting to expose misappropriation of government funds and alleged connections between politicians and criminal groups, the threats are exacerbated. Threats can include bullying, intimidating phone calls, assaults, even murder—often in connivance with local leaders, activists said. One, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, said that after using a request to expose irregular admission criteria at a college, he was hounded out of his job and harassed.

Nikhil Dey, of the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information, said that although those filing a request need to provide only their name and a P.O. Box number, many include their full address. Because these details are made public, personal details of the activists are exposed.

In some cases, those who request information are murdered. In 2010, Amit Jethwa, an activist who used Right to Information act requests to expose illegal mining in the Gir forests of Gujarat, was shot dead. Three years later, Dinu Bogha Solanki, a member of parliament from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, was charged with murder and criminal conspiracy for allegedly being the mastermind behind the killing. Solanki has petitioned the high court to have the case against him dropped, saying that it is politically motivated, according to reports. At the time of publication, the trial was on going.

In other cases, activists have reported being falsely implicated in criminal cases by the same officials who were named in the documents accessed through Right to Information requests, according to accounts given at a 2013 Times of India and National Campaign for People’s Right to Information workshop about the use of the act.

Despite the risks, the act has helped citizens expose wrongdoing and local media often pursue the cases. In 2011, for instance, a request filed by Agrawal appeared to show that Andimuthu Raja, India’s telecommunications minister under Congress Party rule, had undercharged mobile phone companies for spectrum allocation licenses, according to reports. When the press uncovered more alleged wrongdoing, Raja resigned from government. The former minister, who denies the allegations against him, is currently on trial, according to reports.

Agrawal said that because his requests focus on system reform rather than potential criminal activity, he has been threatened only once in the past 10 years, when he was investigating claims that a municipal authority had illegally built a cremation pyre. After his initial request for information showed apparent wrongdoing, Agrawal and a crew from the state-owned broadcaster Doordarshan Television visited the site of the alleged pyre where, they say, the crew was attacked. Agrawal said he escaped thanks to his driver.

A reporter who uses information requests for the basis of his work, said that journalists who use the act generally face less risk of harassment. Shyamlal Yadav, an investigative reporter for The Indian Express, said neither he nor his paper had been threatened after filing an information request. He said he was safer than activists by virtue of being a journalist for a large organization and because he files the requests on behalf of the paper.

But Yadav, who twice won the Ramnath Goenka Memorial Award for Excellence in Journalism, said he is in a minority when it comes to journalists using information act requests in their reporting. “There are two reasons for this,” Yadav said. “First, owners and editors don’t give journalists a chance [to pursue information act-based stories] and second, journalists themselves don’t have the patience to wait for a month.” Under the act, officials have a 30-day period to respond to a request. Yadav added, “There’s a lot of patience required to do this kind of work and it does have a big impact.”