Turkey is notorious as a leading jailer of journalists worldwide, a fact that can overshadow the other problems for its press. Alongside the risk of arrest, journalists must contend with daily interference. From police denying reporters access to courtrooms, arbitrarily moving them on or forcing them to leave certain areas when they are reporting on events from the street, or confiscating cameras—seemingly every reporter has a story to share.

CPJ spoke with six journalists about their experiences. All have been taken into custody in relation to their work at least once. Ahmet Kanbal, a reporter from the pro-Kurdish Mezopotamya News Agency (MA), said he doesn’t even remember how many times police have detained him over the course of his journalism career, but he estimated it was at least 10.

“They are usually detentions that happen following a story, without a reason or justification being offered,” he said, adding that once in custody police accuse journalists of either being a member of or making propaganda for an outlawed organization, or acting on behalf on one, at the very least. “Usually they go through our social media account[s], find a critical post and use it as the justification of the detainment. If they cannot find something on the social media, they find a story of yours at the website of the outlet you work for and that becomes the subject of accusation. If they cannot find that too, then the simplest question of accusation is ‘What were you doing there?’ ” Kanbal said.

Tunca Öğreten, from the Turkish service of Deutsche Welle, has been detained only once, but his experience mirrored that of Kanbal. “The justification brought by the prosecution for the detention was ‘terrorist organization membership’. However, neither the cops who came to the house, nor the interrogation cops, nor the prosecution could not come up with a suitable [terrorist] organization for me,” he said, adding that it seemed clear to him that authorities first went through his devices and then decided which organization would be the best fit.

Authorities confiscating equipment and then holding on to it for long periods is another issue. When police raided Öğreten’s house in Istanbul on December 25, 2016, they took three computers, two iPads, two iPods, three hard drives and a cell phone. Öğreten was released pending trial on December 6, 2017 but, he said, his property was not returned until November 10, 2019.

Sometimes the confiscated equipment is not returned at all. Safiye Alağaş, from the pro-Kurdish JinNews, said that the last time she saw her computer, cell phone and SIM card was when she spent four days in custody in 2011. Zehra Doğan, a former reporter with the shuttered, pro-Kurdish JİNHA, said authorities failed to return her cell phone and SIM card. And Canan Coşkun, a freelancer who used to work for the opposition daily Cumhuriyet, said she has no idea when she will get her laptop, cell phone and portable modem back, after police in Giresun confiscated the devices when she was detained last month.

Hayri Tunç, a reporter at the socialist news website Gazete Fersude, said he has paid a heavy toll: between 2014 and 2016, police confiscated three computers and three cell phones that have not been returned, and broke three cameras. Twice, his cameras were broken by pressurized water fired from police tanks and in one instance, a police officer kicked it.

As of late 2019, the Interior Ministry had not responded to a letter from CPJ requesting comment on these issues and other incidents the journalists raised.

The risk of police harassment is exacerbated for those working for an outlet that Turkish authorities deem undesirable. Kanbal said that in legal papers his outlet, MA, is mentioned as the media outlet of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) despite it being a licensed, tax-paying operation. Doğan agreed, saying that in her experience, the security forces aim to make life difficult for Kurdish journalists.

But prejudice from the authorities is not exclusive to the pro-Kurdish media. Öğreten said that journalists working for foreign outlets are considered “spies.” He said that police follow his movements when he reports from eastern and south eastern Turkey, where the Kurdish opposition is traditionally strong. The police have even come to hotels and harassed him and the establishment for letting him stay, he said.

At least two of the journalists said police mistreated them. Doğan said she was subjected to a strip search against her will and that the police asked her to be “an agent for the state” and to testify against people she did not know in exchange for her release, plastic surgery, and a house abroad. When she refused to comply, she said, police shouted at her and threatened that she would spend the rest of her life in prison.

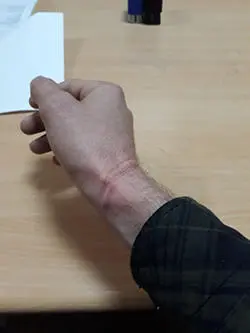

Kanbal said that the most comment mistreatment he has experienced is police cuffing his hands behind his back or insulting him. He said that police have beaten him several times over the years, and that he filed criminal complaints in 2014 and 2017. “We have given up on hope from the judiciary in this situation but I have given the relevant documentation regarding the two recent incidents to my lawyer,” he said.

The journalists agreed there was no simple solution. Tunç said he believes journalism should be recognized as a risky profession that a specific law should be introduced to protect journalists’ rights.

Alağaş said that the challenges for journalists were ultimately related to wider issues around democracy in Turkey and the lack of a democratic constitution to protect journalism. “The journalist’s right to report is not to be interfered with, no matter what,” she said, adding that it should be up to the public, not the authorities, to decide who is a journalist. “The police do not see me as a journalist; the state does not see me as a journalist. But I am a journalist. The public sees me as a journalist too. Moreover, I believe I fulfill what is needed to be a journalist. It is not for the police to determine if we are journalists or not.”

Doğan added, “The AKP government has demonized each journalist or media outlet which criticizes it [and] exposes its wrongs. This demonization has been met with acceptance on the levels of the people, security forces and the judiciary.” She said she believes that the press freedom problem has evolved from a political problem into a sociological one. “I believe changing the perception toward independent journalists with professional ethics will be a process that may take years.”