Read this story en français in collaboration with AyiboPost.

Violent attacks and threats waged by a coalition of militarized gangs are among the many risks Haitian journalists face to report the news amid intensifying insecurity in the country’s capital city, Port-au-Prince. Yet as a rotating cast of transitional leaders hope to restore order across the Caribbean nation, journalists say a lack of transparency and hostility from government authorities have left many media outlets and their reporters without the protections they desperately need to safely do their jobs.

Haiti has undergone three changes of government in the past 18 months as part of a rotating seven-member presidential transition council installed after President Jovenel Moïse’s 2021 assassination, with gangs forcing out the country’s interim prime minister in 2024.

Media outlets have filed complaints that the interim government has displayed a lack of transparency in its efforts to hold the country together; this includes the failure to publish its budget — passed in secret — as well as the controversial hiring of foreign military contractors who have used armed drones to battle gangs.

Since Moïse’s assassination plunged the country into lawlessness and impunity, CPJ has documented the killings of 12 journalists and the destruction of at least six radio stations — mostly at the hands of the gangs. In 2025, CPJ provided financial support to 17 Haitian journalists, facing incidents related to their work, in the form of grants to cover needs such as psychosocial support, medical and relocation costs.

Widlore Mérancourt, the editor-in-chief of the independent AyiboPost news site, said the state of journalism in Haiti should “alarm anyone who believes in the essential role of our craft — helping citizens make sense of a country marked by violence, corruption, and opacity.” Increasingly, Mérancourt warned that government officials and ministries are “shutting their doors, barring state employees from speaking with reporters,” which threatens to leave Haiti’s information-deprived populace in the dark.

Fighting for transparency

The office of the current Prime Minister Alix Fils-Aimé hosts a weekly Tuesday meeting with the media where only basic information about official scheduled events is shared, said Denel Sainton, a journalist with Radio TV Caraibes. “Any information that might interest the public, they don’t share,” Sainton said.

While ministers use these Tuesday appearances and issue statements, they do not hold press conferences or take questions, Sainton shared. “I wouldn’t call it information, more like propaganda,” he added, noting that the absence of a Freedom of Information law prevents many journalists from pursuing access to information.

In a letter in early December, the country’s Citizen Protector, or public ombudsman, Jean Wilner Morin, challenged Prime Minister Fils-Aimé over the deteriorating security in several communities in the central Artibonite, after the government failed to address a massacre in the town of Pont-Sondé, besieged by gangs.

“The authorities’ silence in the face of the daily tragedies of Haitians is a constant during this transition. It reflects the executive’s — the CPT and the government — detachment from reality,” wrote The Nouvelliste, Haiti’s main daily newspaper.

After five years without elections for any public office, from the president to municipalities, Guyler Delva, a longstanding Haitian media advocate and director of the SOS Journalistes press freedom group, told CPJ that he believes the country has devolved into a thinly “disguised dictatorship.”

“Since the Duvalier dictatorship [1957-1986], press muzzling in Haiti had never been such a central element of the government’s policy,” said Delva.

The transitional government has scheduled long overdue elections for August 2026, despite warnings by Haitian media outlets about the dangers voters — and journalists — will face from gangs who still control large parts of the country.

More than 200 political parties have already registered for the elections, and the injection of public funding that potentially comes with running.

CPJ’s emailed requests for comment to the office of interim President Laurent Saint-Cyr and Prime Minister Fils-Aimé did not receive any response.

Exposing a pattern of corruption

Haiti consistently ranks among the most corrupt countries in the world by Transparency International, a global movement that grades countries every year. It is currently the 16th worst offender out of 180 countries.

The government has tried to institute measures to improve transparency, including a national hotline to report corruption, but these remain woefully inadequate, according to William O’Neill, the United Nations expert on human rights in Haiti.

“Everybody you talk to in Haiti knows that this corruption is so rife in every ministry and in every aspect of Haitian life and it’s got to be rooted out somehow,” said O’Neill. Out of 87 corruption investigations since 2020 by a special unit in the Justice Ministry, only one resulted in a conviction, he noted.

A United Nations report accused the Haitian government of spending thousands of dollars on lavish cocktail parties to celebrate new appointments while failing to adequately address allegations of rampant corruption. When it comes to the press, the government has also been accused of playing favorites, distributing its limited largesse to outlets that offer the least criticism or help spread government propaganda.

Intensifying intimidation

The National Telecommunications Council (CONATEL) suspended the radio show Boukante Lapawòl (Exchange of Words) on Radio Mega for eight months last November after wanted Haitian gang leader, Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, called into the show and alleged that he was offered a large bribe by a member of the ruling Presidential Transition Council to negotiate peace with the gangs. CONATEL dismissed the interview as disseminating “propaganda” in support of the gangs.

Boukante Lapawòl returned to the air in June 2025, despite an arrest warrant for its host Guerrier Henri, who was forced to take refuge in Canada. Henri returned to Haiti recently and voluntarily agreed to meet with the police, who have taken no further action against him.

Other journalists said they have also come under pressure when they defended Henri.

“That’s when my problems began,” said Radio TV Caraibes’ Sainton. He said he received warnings that he could be arrested as well if he kept defending Henri. “My bosses told me they got word from the government that I should watch out,” Sainton added.

SOS Journalistes decried the campaign of intimidation against Henri as “a serious, deliberate, and clear attack on press freedom,” and called on the government to provide evidence to support the accusations.

The Haitian government alleged that Radio Mega violated broadcast laws by interviewing wanted criminals and terrorists on its airwaves. Two of the country’s largest gangs, Viv Ansamn, led by Cherizier, and Gran Grif, were designated by the United States as Foreign Terrorist Organizations in May this year.

Radio Mega executives argued that people and groups accused of terrorism are regularly interviewed by respected media outlets, among them recently Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, who was charged of narco-terrorism by the United States.

Last year, foreign journalists with Reuters interviewed Cherizier in Haiti, controversially delivering gifts of cigarettes and whisky. “Only when we Haitians do interviews suddenly it’s a problem,” said Radio Mega owner, Alex Saint-Surin.

After Henri’s interview with Cherizier, Saint-Surin said the police came looking for the host at the radio station a few days later.

“They told us we had to stop doing propaganda for the gangs. They only want us to broadcast their (government) propaganda,” said Saint-Surin.

CPJ asked the police to respond via text message, but they declined to comment.

A spokesman for the prime minister, Emmanuel Jean François, called allegations of media intimidation “unfounded,” adding that Haiti is dealing with a “complex” socio-economic, humanitarian and security situation.

“If there is one sector in Haiti that enjoys considerable freedom, it is the press,” he told CPJ in a text message.

A battle to restore order

The United Nations has backed the deployment of a 5,000-strong international Gang Suppression Force in Haiti, but little funds or manpower have been committed yet, and officials said they do not expect it to be operational before June 2026. So far, the Haitian police are backed only by a 1,000-strong Kenyan-led mission, plus about 100 foreign security contractors hired by the government and equipped with armed drones.

The government’s battle to restore order in the country has raised concern about collateral damage. Several drone attacks against gangs have resulted in civilian casualties, including eight children who were killed at a birthday party in September.

During a November hearing in Miami, Pedro Vaca, the special rapporteur for Freedom of Expression at the Organization of American States (OAS), explained that trafficking of guns “also undermines the Haitian state ability to fulfill its obligations to protect journalists and investigate crimes against them.”

A “visible contraction” of the public space journalists can operate in forced some journalists to limit their coverage of “sensitive issues” while others choose to “abandon the profession altogether,” Vaca said.

“This impunity fuels a vicious cycle in which attacks against the press become an easy barrier to carry out and less likely to be punished,” he added.

Critics say these dire times make it even more essential for government accountability to rebuild public confidence in a democratic outcome.

Last year on December 24, two journalists were killed and seven other injured after the Minister of Health invited the media to the reopening of the central hospital in Port-au-Prince. Gang members were lying in wait and opened fire.

The government accepted responsibility and paid $7,500 to the family of each journalist killed and smaller sums to the rest, varying from $750 to $3,500. One of the injured journalists was left stranded and penniless in Cuba where he continues to receive facial reconstruction treatment for a bullet that shattered his jaw.

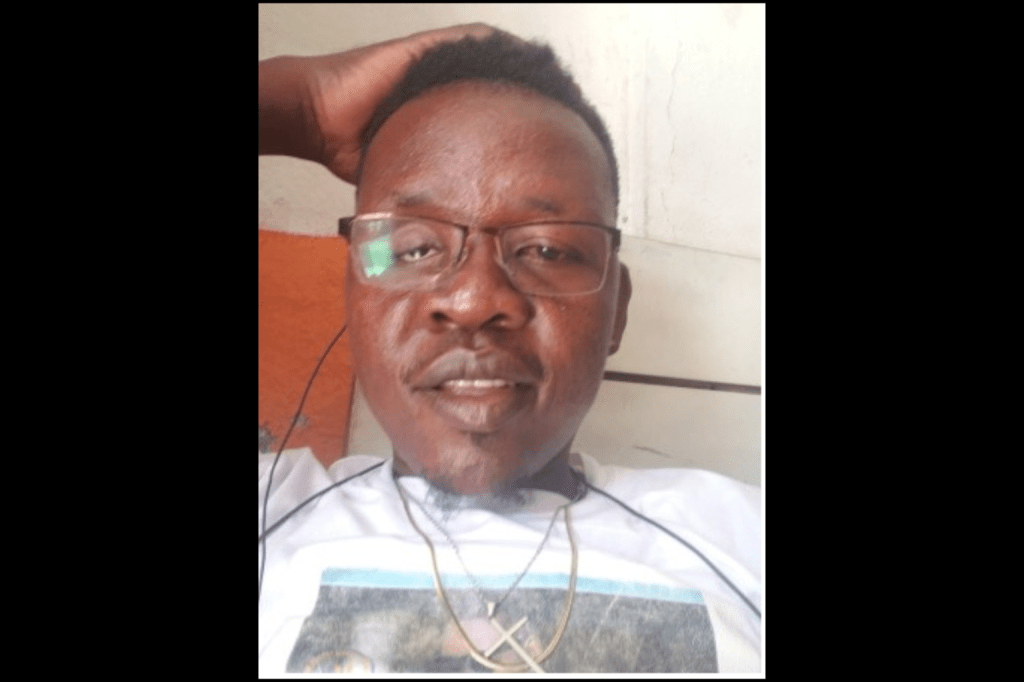

In February 2024, journalist Jean Marc Jean was struck in the face by a tear gas canister fired at protestors by police and lost an eye. His family received $3,000 from the police to cover his medical expenses, but the government offered no compensation, despite recognizing its officers mishandled the protest.

“We are constantly betrayed and abandoned,” said Jean, who has continued his work as a journalist despite losing an eye. He added, “We live in a country where press freedom is regularly threatened, police violence is rarely sanctioned, and our rights are ignored.”