In August 2014 two journalists living more than 4,000 miles apart slipped across a border to find safety: one with his wife and three children, the other alone. Idrak Abbasov, from Azerbaijan, and Sanna Camara, from Gambia, faced imprisonment because of their reporting. Neither has been able to return home.

Their stories, along with those of Bob Rugurika, a radio director from Burundi, and Sevgi Akarçeşme, an editor from Turkey, reflect the experiences faced by the many journalists forced to flee each year after being persecuted for their reporting. Each of the four journalists with whom CPJ spoke before World Refugee Day had to make the tough decision between exile or imprisonment.

Azerbaijan: ‘I didn’t know who to turn to’

Idrak Abbasov, a veteran reporter from Azerbaijan, said he had been threatened before over his reporting, but when a colleague warned him in August 2014 that he could be arrested he decided it was time to take his wife and three young children to a safer place. He said that to avoid attracting attention, they left their home in the capital, Baku, with little luggage.

The week before Abbasov left the country, the prosecutor general’s office had raided the offices of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, a Baku-based press freedom group where he worked, confiscating computers and equipment as part of a crackdown on civil society in Azerbaijan.

It was not the first time that Abbasov, who also worked for the independent newspaper Zerkalo, has been targeted for his work. CPJ documented in 2012 how he was hospitalized after being beaten while covering forced evictions in the lead up to the Eurovision Song Contest that Baku hosted that year. Despite a concussion, broken ribs and teeth, damage to his kidney, and needing eye surgery, Abbasov continued to work as a journalist.

Abbasov said that to avoid alerting authorities to his decision to leave, he told friends and colleagues he was taking his family to Turkey so his son could receive medical care. On August 19, Abbasov drove his wife and children to the edge of Baku, where they left the car. The family traveled across the border to Georgia and used false names to check into a hotel in Rustavi, where they stayed for two days.

“Nobody expected us in Georgia, I did not know what to do, who to turn to,” he said. Abbasov said that to explain the absence of luggage, he and his wife told hotel staff they were on vacation and that friends had their belongings. By this time, the journalist’s bank account had been frozen and plain-clothed men had visited his home and the home of his father-in-law, looking for him. Relatives in Azerbaijan told Abbasov police had detained his brother-in-law for two days, questioning him about the journalist’s whereabouts.

With help from CPJ and other press freedom groups, Abbasov and his family left Rustavi for Georgia’s capital, Tblisi. They were farther from the border, but Abbasov said he feared that Azeri secret services would still be able to reach them. The family changed their residence several times and rarely went outside. Abbasov said it was a hot summer and his children wanted to go outside to play, but he couldn’t let them.

In September 2014 the family flew to Chernihiv in Ukraine, where they stayed at the Human Rights House, a shelter run as part of a larger network of human rights defenders and organizations. After two months the journalist moved with his family to a shelter in Vilnius, also run by human rights groups.

In January 2015 Abbasov and his family moved to Norway, after being accepted by the International Cities of Refuge Network and being granted a three-year residency permit. He and his wife have since had a fourth child. Abbasov said that his older children were confused when they left their home, but that they have settled into life in Norway and understand the family will not return to Azerbaijan.

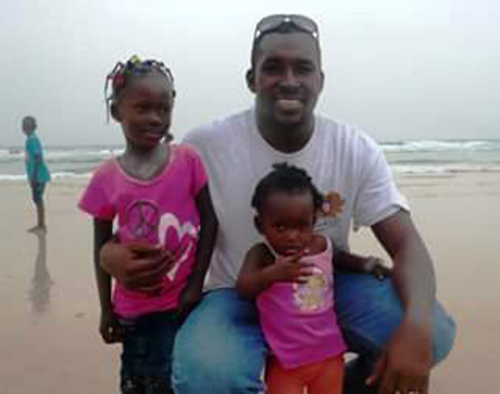

Gambia: ‘My daughter asks when I’m coming home’

In June 2014, Sanna Camara was arrested for the third time over his reporting. Unable to report freely in his own country, and fearing he would be detained again, Camara said he knew he had no hope of staying in Gambia. Camara told CPJ that his last arrest came on the same day that a story he wrote on human trafficking appeared in The Standard newspaper. Authorities accused him of publishing false news and he was released on bail on the condition that he report to police headquarters in Banjul three times a week.

A week before he fled, Camara said that a contact at the police department tipped him off that there was enough evidence to proceed with his case. Because he needed permission to travel, even within Gambia, the journalist said he told police he planned to visit his parents about 180 miles from the capital.

Instead of visiting his family, Camara went directly to the border. Knowing fewer guards would be patrolling when it was hot, he waited until the sun was at its highest point before crossing into Senegal, where he tried to register as a refugee.

When Camara first arrived in Senegal’s capital, Dakar, he found an apartment large enough so that his wife and three children, who are between two and six years old, could join him. But, Camara said, he realized he would not be able to support his family in exile like he had at home. The journalist could live without breakfast, but he could not deprive his family of three meals a day, he said. His wife and children returned to Gambia after a few weeks and Camara moved into a single room, where he still lives today. “I miss my children. Every time I talk to my daughter she asks when I’m coming home,” Camara said.

In March 2015, Senegal rejected Camara’s application for refugee status. No reason was given. Camara said that the applications of several Gambian journalists who fled to Dakar before him were also rejected. He is currently appealing the decision.

CPJ has found that most members of the media who are forced to flee are not able to continue their work in journalism, but Camara writes part-time for Gambian news websites and in May started contributing to the independent global news service, Democracy Watch News. He also reports on politics, human rights, and freedom of expression issues for his blog, GambiaBeat.

“In Senegal I have a lot of freedom to investigate human trafficking. I have interviewed over a dozen human trafficking victims. I would not be able to do this work in Gambia. I would not have the security to do this,” Camara said. “It’s not the best, but it is more secure than in Gambia.”

Burundi: ‘I was paralyzed by the idea of exile’

In May 2015, radio journalist Bob Rugurika was forced to flee Burundi for the third time since 2010 because of threats over his reporting. Rugurika said that the first two times he left, both related to his investigations into the murder of human rights defender Ernest Manirumva, he felt safe enough to eventually return home, even though he and his wife received death threats.

His desire to contribute positively to society in Burundi always brought him back. “I felt a sense of outrage, guilt sometimes as if we [journalists] were not able to prevent this situation of war in which Burundi plunged. I was torn by a sense of desperation and desire to want to keep fighting no matter what,” he said.

Rugurika’s most recent flight across the border was different.

In January 2015 CPJ reported how the director of the privately owned Burundi station, Radio Publique Africaine, had been charged with complicity in murder and breach of public solidarity, after the station broadcast an interview in which a guest claimed to be involved in the murder of three Italian nuns. During the broadcast, the guest implicated several intelligence and police officers in the murders. He did not provide any evidence.

After refusing to say where the guest was located, Rugurika was arrested on January 19, 2015 and held for one month. The journalist told CPJ he was used to receiving threats but after his conditional release in February the threats intensified and his home was attacked, forcing him to go into hiding. Rugurika said that after two months in hiding his life had become unbearable and he realized he had to leave Burundi.

On May 8, 2015, as violent demonstrations took place in the capital, Bumjumbura, in response to President Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term, Rugurika prepared to leave. Since the start of unrest in that year, coupled with a government crackdown on the independent press, CPJ has been aware of more than 100 journalists who have fled Burundi.

In Rugurika’s case, prosecutors banned the journalist from traveling, so he kept his plans secret. Rugurika said that under the pretense of working on a story, he arranged for a driver from his radio station to take him close to the Rwandan border. The journalist told the driver he needed to meet his source at a discreet location and then used a motorcycle to travel to a part of the border that was not widely patrolled.

Rugurika was able to cross easily into Rwanda, where someone was waiting to take him to the capital, Kigali. From there Rugurika traveled to Nairobi in Kenya, but he later returned to Kigali to be with other Burundian journalists who fled to Rwanda, saying it is the most secure country in the region.

“The first six months have been difficult,” he said. “I was paralyzed by the idea of exile. This is the first time I had decided to flee the country without knowing exactly when I would return.”

Rugurika continues to work as a journalist and has founded Humura Burundi, an online magazine that provides news on Burundi.

Turkey: ‘My whole life was in Istanbul’

In the past year, CPJ has documented an escalation in Turkey’s crackdown on the press, with arrests, forced takeovers at news outlets, and legal action. One of the casualties of the crackdown is Sevgi Akarçeşme, an editor at Today’s Zaman, who was forced to flee in March 2016 for fear of arrest.

In December 2015, Akarçeşme was celebrating being appointed the first female editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman. Three months later, on March 4, an Istanbul court ruled that court-appointed trustees should take over the English-language paper, together with its sister paper, Zaman, after the papers were accused of terrorist propaganda. By the time of the takeover, there were at least 18 journalists behind bars in Turkey, CPJ research shows.

Akarçeşme said that after the takeover and being handed a 17-month suspended prison sentence in December 2015 for allegedly insulting the prime minister in a tweet, she worried she would be either banned from traveling or imprisoned. Numerous colleagues have been sentenced to jail, including Ekrem Dumanlı, the editor-in-chief of Zaman, in December 2014, and Bülent Keneş the former editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman, in October 2015. Dumanlı left the country, and Keneş has been released pending trial, but is under a travel ban. Akarçeşme said she felt frustrated and helpless seeing her colleagues arrested arbitrarily, “I have almost no faith left in the judicial system in Turkey,” she said.

Fearing she would face the same fate, Akarçeşme said she decided to leave Turkey before a travel ban could be imposed. On March 6 she bought a plane ticket, packed her belongings and, within a few hours, was on a flight to Brussels. Akarçeşme said it felt like she was in a movie and that she didn’t feel safe until the plane took off.

“It has changed me. This whole experience has been changing me. I try to look at it in a positive way. I suffer, but we grow when we suffer,” she said. “Secretly, I am still hoping for a miracle. I hope that a miracle will happen and I will be able to go back. It doesn’t seem very likely in the foreseeable future though.”

The journalist added: “I still don’t know how long I will have to be away from my home country. It’s kind of heartbreaking because, after all, it’s my hometown, Istanbul. My whole family lives there. My whole life was in Istanbul. Even though I traveled a lot and I studied in the United States, being forced to leave your country is something else. It feels truly terrible. To leave your country with only two suitcases, not knowing what to do, not having a job, not having anyone next to you.”