When it comes to abusive readers’ comments and tweets from Internet trolls, Katherine O’Donnell has heard it all. For years, O’Donnell, who is night editor of the Scottish edition of the U.K.’s The Times, has borne the brunt of personal attacks, including about her gender, from online trolls who take umbrage at articles in her newspaper.

“They say never read below the line,” O’Donnell said in an October 2015 email. “My Twitter feed has its share of blocked trolls, including a host of cybernats [Scottish nationalist extremists] who have not been shy in denigrating my trans status when castigating me for the views expressed in The Times.”

For the most part O’Donnell, who has worked at The Times for more than 12 years, shrugs off the comments, saying, “I’m not a spokeswoman for trans people. I’m a journalist who happens to be trans.”

The U.K. is at the more tolerant end of the spectrum regarding gender status, and most conflicts affecting transgender people typically include anonymous online attacks, discrimination, or lack of sensitivity among peers or in the way the subject is reported in the press. But even in the U.K., violence is sometimes directed toward transgender people. At the more dangerous end of the spectrum are countries like Uganda, where narrow views of sex and gender status are rigidly enforced by the government and violence is a greater risk, making it harder for transgender people to shrug off verbal or online attacks.

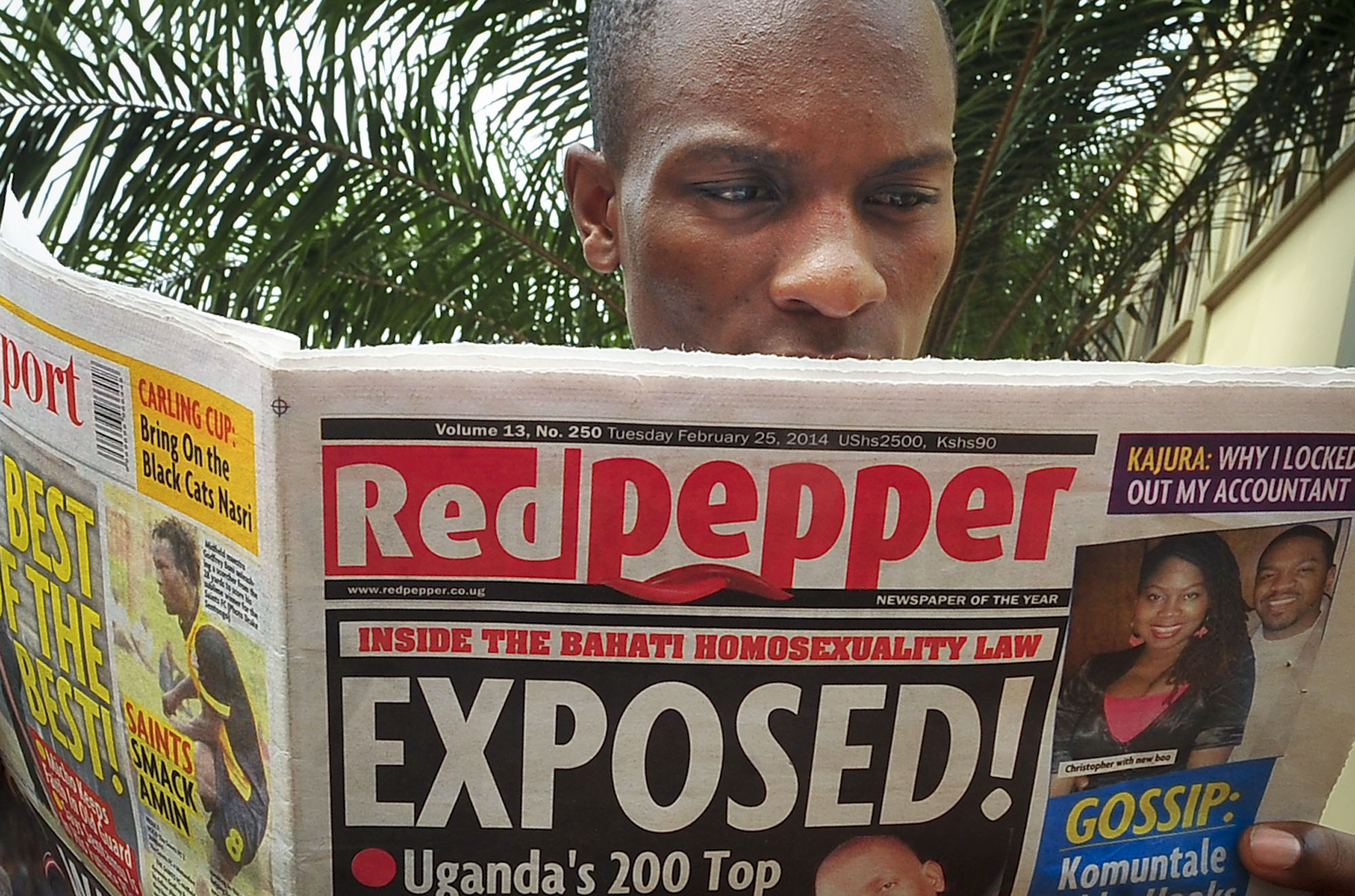

Advocacy groups tracking conditions in Uganda have reported on attacks, sexual violence and, in some cases, legal action against transgender people. Victims of gender-related crimes often do not report the attacks to authorities for fear of legal action and further harassment. Members of the LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) community in Uganda also face the threat of violence after being publicly outed, as happened in February 2014, when two people were reported to have been attacked after the newspaper Red Pepper published a list of “200 top homosexuals” under the headline “Exposed.”

For Uganda’s press, reporting on transgender issues can also lead to charges of “promoting homosexuality.” An anti-homosexuality law under which gays could face life imprisonment was repealed in 2014, but a draft law set to replace it threatens seven-year jail terms for the “promotion of homosexuality.”

Among gender issues, transexualism is at the forefront of changing mores around the world, sometimes with dangerous implications, including for journalists. Despite the risks of legal action or physical attacks, many journalists insist on covering related issues in Uganda. The people behind Kuchu Times, an outletset up to provide a platform for LGBTI voices and to try to counter negative reporting in the mainstream press, say they are determined to take on ill-informed views. The outlet regularly features accounts either from transgender contributors about their experiences or news about violence and discrimination against transgender and gay people, through its news website and online radio and television station. Some of the contributors and staff use pseudonyms to protect them from prosecution under Uganda’s anti-gay laws.

“Discrimination is our lived reality,” said a staff member and contributor to Kuchu Times who asked to be identified only as Ruth M. “However, this hasn’t stopped our reporters from ensuring that stories from the transgender and LGB family are heard. Transphobia is an issue that we as a LGBTI community continue to struggle with, hence our trans-identifying reporters continue to face stigma and discrimination in their work.”

Due to the risk of attacks, only a few have access to the studio that the outlet uses for its online broadcasts, and the reporters and contributors, especially those who are transgender, are advised to take extra precautions while working, Ruth M. said, adding, “We operate in an already hostile and biased environment.”

There is reason to be cautious. Uganda is one of more than 30 African countries where being gay is criminalized and, although transgender people are not always gay, they often fall under discriminatory legislation.

Violence and threats against this group can also lead to murder. Between 2008 and September 2015, 1,933 murders of transgender and gender-variant (not identifying as either male or female) people were reported worldwide, with nine victims killed in African countries, including two in Uganda, according to the Berlin-based regional organization Transgender Europe, whose ongoing research project on Trans Murder Monitoring tracks the deaths of transgender people globally. The results of this monitoring project show that in the U.K. during the same period, seven transgender people were murdered, including one in 2015. The country with the highest figure was Brazil, with more than 770 reported murders.

Kikonyogo Kivumbi, executive director of Uganda Health and Science Press Association, described transgender people as “a minority within a minority” and said “there is little understanding in Uganda about trans people.” According to Kivumbi, journalists writing about transgender issues “receive reprisal, reaction, [and are] undermined by editors and fellow staff because many people in Uganda believe all trans people are gay.”

Journalists in more liberal countries such as the U.K. face a different array of threats, but even there, not everyone is inured to the lack of understanding or the vitriol on social media and in online comments. Jennie Kermode, chair of London-based Trans Media Watch, said that although she is not aware of any cases in the U.K. where a threat made on Twitter led to an assault, fear remains.

Mainstream news outlets in the U.K. are giving more prominent space to transgender issues, and transgender reporters are assuming more visible roles. Yet even in the U.K., reporters who cover the subject, or who happen to be transgender, may find themselves the focus of cruel and abusive comments, including from fellow journalists. Often, they also have to deal with sensational reporting.

“Over the last year, there have been some frankly abysmal blunders around the reporting of trans people,” O’Donnell said. Some news outlets, including the New Statesman, Daily Mail, and The Spectator have “devoted a lot of space, and sometimes, gleefully, to the activities and views of TERFs [Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists] who are dedicated to making the lives of trans people even more difficult,” she said.

In discussing these issues in the U.K., many journalists and advocates bring up columnist Julie Burchill, whose work has been featured in several national newspapers, including The Spectator and The Sunday Times, as someone who has written negatively about the transgender community. In March 2014, Burchill sparked angry debate after she left abusive comments under an article that journalist Paris Lees wrote for Vice magazine about enjoying the attention of men on the street. The comments, which included crude remarks about Lees and about gender reassignment surgery, and the claim that only humans born female can refer to themselves as women, were later deleted, according to Pink News, which covers LGBTI issues and reported that Burchill added an apology that was also later deleted.

Burchill did not respond to emailed requests for comment, forwarded to her by her book publisher and sent through news outlets to which she contributes, about the Paris Lees incident and claims that online harassment from a fellow journalist could deter transgender reporters.

Critics say such behavior has the potential to undermine growing sensitivity to gender issues in the mainstream British press and the work of organizations such as media groups All About Trans and Trans Media Watch to ensure fairer reporting on transgender people.

Kermode said getting editors to recognize the problem of such attacks is crucial to changing the media’s approach to transgender reporting. “While we are very much in favor of freedom of speech and would not object, for instance, to speculation on why people are trans-though for the sake of quality journalism, we’d hope there was some science involved in the argument, we hope people will see that attacks intended to insult or stir up hatred are just as damaging when made against trans people as they are when made against a specific racial or religious group,” Kermode said.

Groups such as Trans Media Watch say one way to counter such abuse is to reduce the unnecessary focus of news reports on an irrelevant transgender angle. O’Donnell, who shares that view, cited as an example news reports about an academic who nearly died after being gored by a stag as she walked home in the Scottish Highlands. “An unprovoked attack by a large wild beast is a solid story by any standard, but several papers were obsessed with the fact that the victim was trans, as if it was somehow pertinent to the attack,” O’Donnell said. “As I pointed out, forcefully but fruitlessly, as it happened, we would not consider it to be germane if the victim was Jewish, or Asian, or gay, so why would we report that she is trans?”

When the victim recovered, she lodged a complaint with the Press Complaints Commission, a regulatory media body in the U.K. The commission found that six U.K. national newspapers–the Daily Mail, The Sun, Daily Telegraph, The Scottish Sun, the Daily Mirror and the Daily Record–had breached the discriminatory clause of the commission’s code through their headlines in May 2014. The newspapers agreed to amend the online versions of the stories, according to the BBC.

The Press Complaints Commission and anti-discrimination laws provide protective measures in the U.K., and All About Trans and Trans Media Watch both actively promote increasing transgender voices in the media and offer advice on how to report sensitively and on dealing with harassment. But in Uganda, laws, including those directed at the media, enable repression or actively persecute the LGBTI community.

Press freedom is already limited in Uganda and journalists of any gender face danger even from those who might be expected to protect them. As the Committee to Protect Journalists has reported, critical news outlets in the country have been suspended and police have been implicated in assaults on journalists. In October 2015, human rights watchdog Privacy International reported that the Ugandan government had bought and used FinFisher surveillance software “to spy on leading opposition members, activists, elected officials, intelligence insiders and journalists following the 2011 election, which President Museveni [won] following evidence of vote-buying and misuse of state funds.”

Coupled with this heavy-handed approach to a critical media are Uganda’s draconian laws affecting the LGBTI community. Colin Stewart, editor and publisher at the international advocacy group Erasing 76 Crimes, which challenges repressive anti-gay legislation, said that anti-LGBTI violence is “distressingly common” in Uganda and in numerous other countries as well, including Jamaica, Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. “Citizens of every country with repressive laws need to learn about the inhumane effects of their country’s anti-LGBTI laws, stigmatization, repression, and discrimination. Kuchu Times does that well for Ugandans.”

Ruth M., of Kuchu Times, acknowledged that the group has had some success. “[Our] platform is currently attracting many visitors, even the anti-gay groups involved, which we hope will help them to learn something about the struggles of LGBTI people and communities in the hope to create attitude change,” she said. By sharing their accounts, the columnists featured in Kuchu Times and on other media platforms hope to create greater empathy and understanding.

Erasing 76 Crimes also uses reporting to inform others of the harmful effects of anti-gay legislation. “We inform people worldwide and, at the same time, provide a media outlet for local activists who are excluded from coverage by homophobic local media,” Stewart said. “Individual stories are a powerful tool that can encourage disempowered sexual minorities to recognize their own worth.”

An example of this kind of proactive reporting is an account by Beyonce Karungi published by Kuchu Times on September 15, 2015, in which she detailed how she had been rejected by her family and felt compelled to turn to sex work to support herself. Alleged harassment by authorities, including an incident in which she says police humiliated her and forced her to “cut my hair to make me look more masculine,” made her not feel safe enough to report being raped.

To amplify the voices of the LGBTI community, Kuchu Times publishes Bombastic Magazine, the first edition of which was distributed across the country in late 2014 with copies also sent to politicians and other key figures, according to Agence France-Presse. Some volunteer distributors in western Uganda reported that they were threatened, and some copies were burned in the country’s eastern region, Agence France-Presse reported.

Ruth M. said that despite its successes, the news outlet struggles to find adequate financial backing. “Local funding is impossible, and we thus have to depend on foreign donations, which don’t come easily,” she said. “Time and again our website and publication Bombastic Magazine have been branded as recruitment tools for homosexuality. This has escalated censorship by authorities into our work.”

Part of Uganda’s draft law to prohibit “promoting homosexuality” is a proposed ban on “funding for purposes of promoting unnatural sexual practices.” To avoid such a conflict, Kuchu Times used crowdsourcing to raise money for the second issue of Bombastic, scheduled for distribution in January 2016. The outlet reports that its IndieGogo campaign exceeded its $5,000 goal, and by early November 2015 had brought in more than $8,300.

In the U.K., transgender journalists sometimes face problems of stereotyping, Kermode said. “It’s very difficult for them to get work writing about anything other than trans issues,” she said, adding, “they all report receiving a lot of personal abuse. This seems, anecdotally, to be worse for the women, so we suspect it’s compounded by misogyny.” Some aspiring transgender reporters are put off by what they consider to be hostile newsrooms, she said.

When Trans Media Watch began operations in 2010, the organization had difficulty finding journalists willing to talk openly about their experiences, Kermode said. “There was a fear of personal attacks and also a fear of being monstered by newspapers, a phenomenon that was quite common at the time. Some of us worked in journalism but simply didn’t publish anything about trans issues or about those aspects of our own lives, while other people felt simply they could never enter the profession.”

O’Donnell, who was late night editor at The Times when she transitioned, said that in her view, “newsrooms are cruel environments and journalists are not always generous.” When she began at The Times, O’Donnell said she found herself quickly promoted. Within a year of starting work there, she was responsible for editing two nightly editions, and when she transitioned, she had the “immediate and unambiguous support” of then-editor Robert Thomson and his deputy, Ben Preston, she said. O’Donnell was also invited to rewrite the paper’s style guide entry for trans people. “A majority of my colleagues, but not all, were thoughtful and kind, if not always entirely understanding,” O’Donnell said. “There were some bad-taste jokes and unpleasant things said, but the transition itself was less difficult that I had anticipated.”

“It was only long after the dust had settled that I began to realize that my career path would come up against active resistance in some quarters and that acceptance and equality was very much conditional,” O’Donnell said. “It’s a work situation that many, many women will recognize.”

O’Donnell said her experience has made her more outspoken. “I have intervened with colleagues whenever I have seen trans people or issues reported inaccurately or unfairly,” she said. “I doubt that this has made me especially popular but to their credit, generally I have been listened to.”

Finding support for sensitive reporting is also a challenge for Ugandan journalists. Kivumbi, of the Uganda Health and Science Press Association, said that journalists in the country often have problems finding outlets willing to run their stories. “It’s not easy for an editor to pass a trans people story or interview in mainstream media,” she said. “What the anti-gay forces have done is to infiltrate and promote hate as part of the internal editorial or broadcast policy in many newsrooms in Uganda.”

Still, Kivumbi added, “Such news channels like Kuchu Times demystify the hate.”

Often hostility toward the transgender community takes the form of online attacks, which is the most pervasive threat in the U.K. Moderators of British news sites are responsible for monitoring hate speech in readers’ comments, and owners of social media accounts have the option of blocking trolls or reporting abuse. In May 2015, the Telegraph reported that Twitter had been asked to block an account by someone impersonating an Australian feminist, and who had paid to have their tweets urging transgender people to kill themselves to be promoted on users’ feeds. A spokesman for Twitter told The Telegraph that the social network bans hate speech and, “As soon as we were made aware we removed the [promoted post] and suspended the account.”

Kermode said her group would like social media groups to take stronger action to prevent or interrupt attacks. “There is a problem on Twitter whereby if one simply blocks somebody one can still see that person’s tweets when they’re forwarded by other people,” she said. “Some people are afraid of not reading hostile tweets because they want to be alert to situations which could spill over into real life. It’s not uncommon for threats of physical violence to be made. It takes a certain toughness to keep working despite this.”

Jessica Jerreat is CPJ’s senior editor, responsible for special reports, including “Balancing Act: Press freedom at risk as EU struggles to match action with values,” and “Drawing the Line: Cartoonists Under Threat.” She previously edited news for the broadsheet press in the United Kingdom, including the Telegraphand the foreign desk of The Times. She has a master’s degree in war, propaganda and society from the University of Kent in Canterbury.