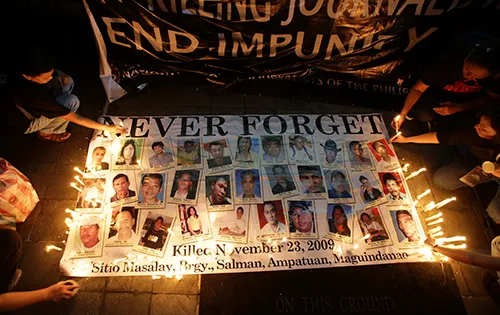

During his final State of the Nation Address this week, President Benigno Aquino III made only a passing mention of the 2009 Maguindanao massacre that killed 57 people, including 32 journalists and media workers. He did not detail any plans for action on the case, despite his vow to deliver justice before his term ends in 2016.

In fact, justice looks more elusive than ever. The alleged mastermind, Andal Ampatuan Sr., died of a heart attack on July 17, according to news reports. His burial in the compound of his family’s mansion, witnessed by members of the community, was a stark contrast to that of the Maguindanao victims, who were shot on a mountainside and buried en masse with a government-owned backhoe. The 74-year-old patriarch of the powerful Ampatuan family was facing multiple counts of conspiracy to murder in connection with the massacre.

The legal proceedings have been beset with delays throughout the six years since the event. Not a single suspect has been convicted.

Furthermore, impunity in media killings across the country has created a chilling effect on the work of journalists. Many are hesitant to report on local politics or investigate corruption. Self-censorship is increasingly utilized as defense against potential retribution.

“After the massacre, I had second thoughts about covering politicians,” Walter Balane, president of the Bukidnon Press Club in the province neighboring Maguindanao, told CPJ by phone. “It has made a dent on how journalists cover the local government. You’re very close to your sources if you’re living in the community. They’re the ones you meet in the public market.”

Since the massacre, nine journalists have been killed in direct relation to their work, CPJ research shows. Another 20 have been killed in less clear circumstances, while many more are threatened, according to CPJ data. The lack of progress in investigating motives and prosecuting suspects compounds the risks of reporting.

“After the massacre, it gave everyone a signal,” Manila-based photojournalist and New York Times contributor Jes Aznar told CPJ by phone. “Even if you’re working with the press, you can still be killed in broad daylight.”

Meanwhile, the Maguindanao trial faces further delays with Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes having applied for a vacancy at the Court of Appeals in July, according to news reports. Solis-Reyes and her family live with armed security personnel because of the trial, which she now plans to leave to a successor.

If Solis-Reyes vacates her post, the courts will “find a way” to ensure the case is “handled at the same pace,” Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, head of the Supreme Court of the Philippines, said, according to reports. Sereno also chairs the Judicial and Bar Council, which vets nominees in the judiciary. “I’m very proud of the pace at which the Maguindanao massacre case is being handled,” she told reporters on July 2.

Of the 197 alleged killers, 15 belong to the Ampatuan family including the alleged mastermind, Andal Amaptuan Sr. and his son, Andal “Unsay” Ampatuan Jr. In March, another son of the family patriarch, Datu Sajid Islam Ampatuan, was released from jail after posting bail for an estimated $264,000, according to news reports.

“As we predicted, securing the amount, which most Filipinos can only dream about, was easy for a member of a clan that had built vast wealth, much of it ill-gotten, during a decade of misrule over Maguindanao province,” the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines said in a statement following his release.

The court had already allowed 17 policemen charged with murder to post bail in October 2014, according to reports said.

While some alleged suspects go free, many witnesses to the massacre and the events surrounding it remain in the government’s witness protection program. Some have also been hunted down and killed for their connection to the trials. In an ambush in 2014, gunmen killed trial witness Denix Sakal, a former driver of Ampatuan Sr., according to reports. In 2012, three witnesses and three relatives of other witnesses were murdered for their connection to the trials, reports said.

Periodic lack of access to the trials has led to questions about the court’s commitment to transparency. In September 2014, journalists were barred from covering the legal proceedings. The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology barred ABS-CBN journalist Ces Oreña-Drilon, saying the courtroom was beyond capacity to accommodate the press. The incident occurred days after Drilon published stories on the alleged smuggling of weapons, cash, cellphones and other items into the jail where the Ampatuans were held.

After doing story on smuggling of a gun,cash&cellphones into Bicutanjail by the Ampatuans we now learn media is banned around its perimeter

— Cecilia Orena-Drilon (@cesdrilon) September 17, 2014

Later that month, reporters for the Philippine Star and Malaya were also denied access to the hearing, one of the reporters wrote.

“Standard practice has it that media outfits, and organizations like NUJP, are given access to the makeshift court, provided no cameras and recording devices should be used during the proceedings,” the NUJP said in a statement in response to the incidents.

The idea that impunity in the massacre has contributed to violence against journalists in the Philippines is more than just a concern on paper.

In Bacoor City, local police have yet to identify the two suspects who fled the scene after they fired multiple shots and killed Rubylita Garcia inside her home in April 2014. Garcia, a reporter for the daily tabloid Remate and a talk show host at dwAD radio, was known for her hard-hitting reporting that exposed wrongdoing in the police force, reports said.

“There are no big or small cases in journalist killings,” said Balane of the Bukidnon Press Club. “Impunity in one case has helped embolden more perpetrators because they see that it doesn’t produce convictions.”

In a more recent case, CPJ is investigating the killing of former Philippine Daily Inquirer correspondent Melinda “Mei” Magsino, who was shot in broad daylight in April. Friends and family attributed the murder to her years-long investigation of local officials. Magsino reported on local corruption and a governor’s alleged links to illegal gambling for news outlets including the Inquirer and Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

“She had no qualms about making anyone mad as long as she wrote the truth,” her friend Bong Macalalad told CPJ by phone. “I’m strongly convinced that her death was connected to her reporting.”

The National Bureau of Investigation, a federal agency, is looking in to motives linked to her previous work as a journalist, reports said, as well as two other theories, a “love triangle” and Facebook posts berating local government officials.

In 2005, CPJ documented death threats against Magsino as she went into hiding following a series of articles she wrote about local corruption in her town of Batangas.

“The list of murdered journalists here [in the Philippines] is too long. I have to survive. I don’t want to become another statistic,” Magsino wrote in 2005, after receiving death threats and prior to leaving the profession, the Inquirer reported.

Since she wrote those words, the Maguindanao massacre increased the number of journalists killed for their work to the point that the Philippines ranks behind only Iraq and Syria as the most deadly country for the media, according to CPJ research. The Philippines is also No. 3 on CPJ’s Impunity Index, which spotlights countries where journalists are murdered and the killers go free.

“It’s not enough that Andal Ampatuan Sr. has died,” Balane said. “The reason why he escaped justice is because justice has been delayed.”