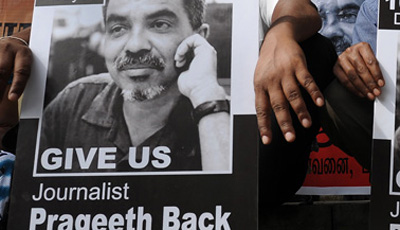

Police never bothered to look for cartoonist Prageeth Eknelygoda. It’s not unusual. By María Salazar-Ferro

Disappearances Unexplained, Amid Hints of Cover-Ups

By María Salazar-Ferro

In the early hours of January 25, 2010, Sandhya Eknelygoda walked to the police station nearest her home on the outskirts of Colombo, Sri Lanka. She had been up all night, frantically looking for her husband. Over the past five months, Prageeth Eknelygoda, a political cartoonist and columnist, had been kidnapped, followed, and threatened. Fearful, the couple had agreed that Prageeth would frequently check in with Sandhya, but he had failed to do so the night before. At the station, the police were dismissive. Eknelygoda was first told that she was at the wrong jurisdiction. Officers then said she was lying, insinuating that her husband was hiding at home. They said staged disappearances were common among those seeking easy fame. Finally, in the evening, a reluctant officer took down her complaint.

Prageeth Eknelygoda has not been heard from since. He is among 35 journalists around the world who have vanished over the past two decades, according to CPJ research. Twenty-nine were local journalists. Most covered conflict, crime, or corruption. Their families struggle to get by financially and psychologically. Their colleagues, fearing a similar fate, censor their own reporting. Without a body or a clear-cut crime, the cases dwell in legal limbo. In at least three cases–including Eknelygoda’s–the sensitive nature of the journalists’ work and the stubborn lack of investigative progress suggest cover-ups by the authorities, who may be linked to the disappearances.

More than half of the disappeared have gone missing in Mexico, Russia, Iraq, and Sri Lanka–countries with high rates of impunity in media murders, according to CPJ’s Impunity Index. Mexico, one of the most dangerous countries for the press, accounts for 11 cases over the past 10 years–all but one under the tenure of President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa. Among the disappeared is María Esther Aguilar Casimbe, a veteran police reporter for the regional dailies El Diario de Zamora and Cambio de Michoacán, who vanished in 2009 near her home in Zamora, a small town in the central state of Michoacán.

Around 11 a.m. on November 11, 2009, Aguilar Casimbe left her house to cover a routine evacuation exercise at a nearby child-care center. She had only her cellphone and a notepad in hand, her sister Carmén told CPJ. Aguilar Casimbe never returned home to take her two young daughters to school. In prior weeks, she had reported on police brutality and a local official accused of corruption.

At least 15 of the journalists who have disappeared worldwide covered crime and official corruption. They include the Franco-Canadian investigative freelancer Guy-André Kieffer, who disappeared from a supermarket parking lot in Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s economic capital, on the evening of April 16, 2004. A commodities expert who specialized in cocoa and coffee, Kieffer had linked the Ivorian cocoa trade to arms deals in recent articles. Although threats, assaults, and harassment of the news media are common in the Ivory Coast, Kieffer long believed that his standing as a foreign journalist would protect him. Only in the days immediately before he went missing did Kieffer admit to a colleague that he was scared, his wife, Osange Silou-Kieffer, told CPJ.

Prageeth Eknelygoda also believed his life was at risk. Days before he disappeared, the journalist told his wife about a hit list on which his name supposedly appeared. It was the pinnacle of an escalating pattern of intimidation, Sandhya Eknelygoda said. In August 2009, the cartoonist had been picked up near his home by unidentified individuals in a white van and held for nearly a day, tied up and blindfolded. After his release, Eknelygoda noticed a vehicle without plates frequently parked outside his home, and heard clicking noises on his phone that made him think it was tapped. He also received menacing calls from individuals who said they would break his arms and legs if he did not stop writing, Eknelygoda’s wife told CPJ.

But the threats were never investigated, according to Sandhya Eknelygoda. Even his 2009 abduction remained unsolved. In fact, attacks on the media have largely gone unpunished during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s time in power. During his eight years as prime minister and now as president, nine journalists have been killed and not a single perpetrator has been brought to justice. CPJ research shows that all those killed had reported on politically sensitive issues and were critical of the government. At the time of his disappearance–two days before the 2010 presidential election–Eknelygoda’s work for the website Lanka eNews was focused on alleged corruption among members of the Rajapaksa family, Sandhya Eknelygoda told CPJ.

Kieffer’s reports apparently also hit a nerve with the Ivorian presidential family. In the months after his disappearance, local and French authorities opened independent investigations that pointed to Michel Legré, a local businessman with whom Kieffer was last seen and who was related by marriage to the first lady at the time, Simone Gbagbo. Legré was arrested in June 2004 and charged in the Ivory Coast with Kieffer’s kidnapping and murder, although no body has been found. In October 2005, Legré, who had accused several officials in the Laurent Gbagbo administration of complicity in the Kieffer affair, was released for lack of evidence. None of those mentioned were ever arrested.

Since, the investigation has had more false starts. In January 2006, French authorities arrested former Ivorian army officer Jean-Tony Oulaï in Paris under suspicion that he headed the commando unit that had abducted Kieffer. Oulaï denied any involvement and was released a month later. Other tips and rumors have followed, including one that led investigators to a body buried in the western region of Issia in January 2012, reviving media attention to the case. But within days, DNA tests determined that the remains were not Kieffer’s, and the investigation returned to square one. Judge Patrick Ramaël, who leads the French investigation, did not respond to a CPJ email seeking comment.

The inquiry into Aguilar Casimbe’s whereabouts has stalled in part due to a lack of witnesses. Some have not come forward out of fear, the journalist’s sister speculates. Others, she said, have died since the investigation began. But the process has also been convoluted. Zamora authorities did not begin to look for the journalist on the day she vanished, asking her family to wait in case Aguilar Casimbe returned. Once an inquiry was opened, it was moved every few weeks to different jurisdictions within the state, with little result. In 2010, the special prosecutor for crimes against the press in Mexico City opened a parallel federal investigation focusing on Aguilar Casimbe’s work. But to date, there have been no answers. The lead investigator on Aguilar Casimbe’s case at the special prosecutor’s office declined to comment, citing official protocol.

In Colombo, frustrated with the lack of progress, Sandhya Eknelygoda has driven an unyielding campaign to find answers. Days after filing her initial complaint, she filed a second with the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, where officials did little more than take her statement. Eknelygoda told CPJ that she wrote to the Commission several times subsequently, but was told in mid-2011 to stop contacting its members. She has also reached out to key figures in the Rajapaksa government. “I have written to the president and first lady, to the attorney general and other cabinet ministers, and to members of parliament appealing for help,” Eknelygoda said. “There has been no answer.”

In February 2010, she filed a writ of habeas corpus before a Colombo court of appeals, asking for information on her husband’s whereabouts or for his remains. Since then, periodic hearings have taken place, but police officers and government officials called to testify about the investigation have not volunteered anything substantive. The lack of government commitment has been obvious from the beginning, said Ruki Fernando, a local human rights activist and Eknelygoda family friend who has attended the hearings. “It’s all technicalities, bureaucracy, and that’s holding them back,” he told CPJ. “If the government is not responsible, then authorities should be eager to find out who is behind it and prove that it’s not them.” Even if Sri Lankan authorities were not behind the disappearance, their lack of action makes them complicit, Fernando said. CPJ sought comment from the Sri Lankan permanent mission to the United Nations in New York, where an official directed inquiries to the embassy in Washington. An embassy official declined to comment.

Abroad, Eknelygoda has made appeals to the U.N. Human Rights Council and to Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. She has traveled to the United States and Europe to speak about the case. At home, she has assumed the role of spokeswoman on the issue of disappearances, organizing vigils and religious services, and has become an advocate for freedom of expression. “There is rarely a protest where Sandhya is not present,” her friend Fernando told CPJ. Eknelygoda’s quest to find her husband has redefined her as public figure–a role that Fernando says seems to engulf her personal life.

Family members of missing journalists are typically more invested in police investigations and other proceedings than those of journalists who have been killed, CPJ found. “More than anything, they want to know what has happened to their loved one,” said Laurence de Barros-Duchêne, mental health coordinator for the International Committee of the Red Cross, in a 2010 interview about the families of missing people. “It becomes an obsession and a source of constant anguish.” According to the family members who spoke to CPJ, however, their pursuit is not for justice, or even details of the alleged crime. The information they seek is simpler: They want to know whether their loved one is alive or dead.

Without remains, said Silou-Kieffer, mourning is impossible, and moving on absurd. “When I’m being practical, I think that he is dead, that he died the night that he went missing,” Silou-Kieffer said of her husband. “But until I have a body, I will never admit that he is dead because the truth is that if he is alive somewhere, and hears me saying he is dead, that is when he will truly die.”

Perseverance in their quest for answers can isolate immediate family members from their communities, friends, and even extended family networks. In Silou-Kieffer’s case, she said, rifts have occurred when friends ask her to admit that her husband is dead. “They say everybody knows that he was murdered, but I don’t know that. I tell them I have no proof,” she said. Eknelygoda said some friends have also stopped associating with her and her children. She told CPJ she believes that some have distanced themselves out of fear, and others because they work for the government and don’t like what she is doing.

Uncertainty permeates the lives of families of the missing. For Silou-Kieffer, after seven years, her husband’s disappearance still casts doubt even on who she is. “How do I describe myself when filling out a routine form? Am I married, single, or a widow?” she asked.

But the psychological impact is perhaps most severe on children. Carmén Aguilar Casimbe said her two nieces, Frida Sofía, 11, and Fátima del Carmén, 10, “live in permanent uncertainty.” “They say very little, but when they see their mother’s photo or something that reminds them of her, they cry and shut down.” Both girls have needed psychological counseling, as have Eknelygoda’s adolescent sons, Sathyajith, 18, and Harith, 15.

Then there are serious financial concerns. In most cases, families have lost their main source of income, requiring significant adjustments to ensure survival. In some, dedication to the case supersedes basic needs. Eknelygoda, for instance, quit her job as an insurance broker after her husband vanished so she could work full-time writing letters, making phone calls, and attending events. She and her boys live off the sale of a book of Prageeth Eknelygoda’s cartoons and writings, supplemented by small donations from family, friends, and organizations like CPJ.

Support from other journalists and human rights groups, abroad and in-country, has been crucial to these families. “There is great comfort in solidarity,” said Eknelygoda. Sri Lankan journalists continue to be harassed, she said, especially her husband’s Lanka eNews colleagues, whose offices were set on fire, forcing the outlet to close and at least one journalist to flee the country. Nonetheless, local journalists have worked relentlessly to keep Eknelygoda’s cause alive.

Likewise, journalists who worked with Kieffer have banded together to demand answers. In the months after his disappearance, a group led by Kieffer’s colleague Aline Richard formed the Truth for Guy-André Kieffer Association, which has closely monitored the case and organizes annual events on the anniversary of his disappearance. “We exist because if there is no pressure on authorities, there is no case,” Richard told CPJ. Ivorian journalists have also supported the case and kept it in the public eye, sending a message to local authorities that they will not stop being vigilant, Silou-Kieffer told CPJ. “Colleagues should never stop seeking answers; they should never give up when one of their own is missing,” said Silou-Kieffer, herself a journalist.

In Mexico, however, the response has been the reverse. Local journalists have generally stayed away from investigating or even publicizing Aguilar Casimbe’s case for fear of reprisal, according to one Michoacán-based journalist who asked not to be identified. “A case like that has a deep effect on colleagues working in the area. It spreads fear,” the journalist said. “It affects all journalists because we do not want the same thing to happen to us.” He told CPJ that most local news outlets steer clear of the Michoacán crime beat that Aguilar Casimbe covered, publishing only official statements. “We have to self-censor because it is the only way to protect ourselves,” he said.

Fernando also believes that the disappearance of Prageeth Eknelygoda was intended to do more than silence a single journalist; it was a message to all Sri Lankan journalists. “When something like this happens,” Fernando said, “journalists are always thinking about when their turn will come, and what they should and should not be printing.” But Sandhya Eknelygoda says self-censorship is not the answer. “Why should I have stopped [my husband] from working?” she asked. “He was not doing anything criminal. He was not doing anything wrong.”

María Salazar-Ferro is CPJ’s Impunity Campaign and Journalist Assistance program coordinator. A native of Bogotá, she studied at Universidad de los Andes, in Bogotá, and graduated from the University of Virginia. She reports on exiled and missing journalists, and has represented CPJ on missions to Mexico and the Philippines, among others.