Journalists are back to work at Uganda’s leading privately owned daily, The Monitor, after a 10-day siege of their newsroom by police. But that does not mean it is business as usual for the nation’s press. The paper’s owners at the Nation Media Group evidently begged and negotiated for its reopening–signaling to other media houses that they should toe the government line or face a similar stranglehold. Although the deliberations were successful in returning the paper to the newsstands, the long-term costs may prove exorbitant.

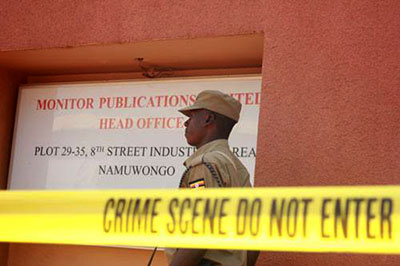

The saga began on May 20 when police raided the premises of The Monitor ostensibly in search of a letter and related documents written by Gen. David Sejusa, the coordinator of intelligence services, on the sensitive question of presidential succession. Sejusa’s letter, addressed to the Internal Security Organization Director-General, alleged an assassination plot against senior officials who reportedly oppose plans for President Yoweri Museveni’s son to succeed him. The Monitor published sections of the letter and a story based on its contents on May 7. Police asked for a court order to search The Monitor for the letter, but abused the directive, sealing off the newspaper’s premises as a crime scene, stopping the printing presses, and disrupting the operations of two sister radio stations, KFM and Dembe FM, housed in the same building. Although The Monitor‘s legal team obtained another court order to reopen the premises, and despite vocal protests by journalists and activists outside, police would not budge. The stranglehold on The Monitor was fiscal as well as physical: the paper’s general finance manager, George Rioba, said it was losing 120 Ugandan shillings (US$48,000) each day of the siege, according to news reports.

And yet there is little indication that police were genuinely interested in obtaining the letter in the first place. Officers told Geoffrey Ssebaggala, national coordinator of the Ugandan Human Rights Network of Journalists, the civil society group that organized the protests against the closure, that they were not willing to open the premises even if they found the letter, Ssebaggala told me. And a government statement issued when the siege of The Monitor ended on May 30 claimed that police would continue the search–but they did not, Monitor political writer Charles Mwanguhya told me. According to Ofwono Opondo, ruling party spokesman and recently appointed executive director of the Media Centre, a state body that issues government press releases, the police had already obtained the letter from another source prior before the siege began, but “wanted to subdue, to show how inconveniencing the state can be.”

While police have raided The Monitor before, this intrusion came at an awkward time for the country, with Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, hosting the African Union Summit and high-profile international visitors in the region. The paper had covered two previous letters written by the general without incident, local journalists said. The problem this time, Opondo said, was the “cocktail of names” Sejusa mentioned in the letter, including those of Museveni’s son and brother. The tension between State House and The Monitor had built up for some time, Managing Editor Don Wanyama told me. The paper had interviewed some months earlier opposition leader Kizza Besigye, who also hinted at the potential succession of Museveni’s son to state house, for example. “In some ways they were attempting to break the backbone of the media at a time when these stories of succession were increasing,” the executive director of the Uganda-based Africa Centre for Media Excellence, Peter Mwesige, told me. “When you have senior generals with such strong statements, they [the government] attempted to nip this in the bud.”

Although the police closure was illegal, and despite the fact that The Monitor has always beat the government in past court cases, the siege eventually ended only after lengthy negotiations between the government and Nation Media Group. The initial discussions involved Opondo and top-level management of The Monitor and the parent company, local journalists told me. The final mediation, however, took place between Museveni himself on one side and the chief executive of Nation Media Group, Linus Gitahi, and the chairman of Monitor Publications, Simon Kagugube, on the other, during two visits to Addis Ababa, where Museveni was attending the AU meetings.

Immediately, users of social media like Twitter and Facebook were awash with criticism that the media company had sold out The Monitor. The Nation Media Group was quick to reject the claims that they had capitulated to a series of government demands, compromising the paper’s independence, in order to reopen. A statement published in the paper on June 6 claimed, “At no time did we make any concessions or sign any agreements.” In interviews after the re-opening, Monitor Managing Director Alex Asiimwe told reporters, “You can ask the government–the only thing we were asked to live by is our editorial policy guidelines. We did not sign anything else.” And yet the media company’s May 27 letter addressed to the president highlighted pledges not included in their much-stated editorial policies. The letter pledged “to be sensitive to and not publish or air stories that can generate tensions, ethnic hatred, cause insecurity or disturb law and order.” At face value these may be exemplary undertakings, but throughout East Africa, authorities routinely use the guise of national security and ethnic tension to censor the press and stifle legitimate public debate on sensitive issues.

“What standards are they using for these terms?” questioned Ssebaggala in an interview with CPJ. “Who defines national security in relation to the press?” Additionally, a commitment in the letter to “seek regular interface with your office” would seem to suggest that media owners are willing to further shorten the leash between State House and the paper.

Perhaps most disturbing, the Nation Media Group letter said the company “highly regretted the story that led to the closure,” without articulating any actual faults with the May 7 article. Indeed, Sejusa had confirmed his penmanship of the letter. But the first Monitor editorial published upon re-opening took an apologetic tone. “We remain committed to fair, balanced journalism. We will make mistakes, because we are human. But we will always try to learn from them and to be better next day.”

“He [Sejusa] confirmed writing the letter, he is the head of intelligence–who else is a better person to comment?” Wanyama, the managing editor, said. The May 7 story also showed that the journalists sought reply from government officials who disputed Sejusa’s claims. “It is not a question what was wrong with the story–in fact, we did not go through the details of what was wrong with the story,” New Media Chairman Gitahi bluntly told reporters after the siege.

During a staff meeting at the paper’s re-opening, the bosses castigated Monitor reporters not for factual mistakes but for failure to achieve stronger sales, according to a recording of the meeting obtained by CPJ. Gitahi, the CEO, told staff that, with 20,000 copies sold daily, reaching an estimated 400,000 readers out of a population of 35 million, “You are not a paper of influence. You are just talking to yourselves.” Chairman Kagugube said, “The reason that [the public] don’t buy is because they think you don’t write very smartly. Don’t deceive yourself that your stories are very hot.” The paper’s owners seemed to be warning staff away from sensitive stories, but they seem also to have forgotten that The Monitor‘s readership is based on its critical stance. The publication, labeled an “enemy paper” by Museveni during a recent parliament hearing, is unlikely to increase sales if tamed.

Kagugube concluded that the paper’s owners would continue to support its journalists, but did not want to have to “beg the way we begged.” The idea that the media owners “begged” in the first place is bad enough. But now Monitor staff members have further worries over their status at the paper, and this could result in self-censorship, local journalists told me. Rumors have circulated that the management may fire certain staff members to ensure the government’s ire is not raised again, they said. Repeated calls for comment to Managing Director Asiimwe went unanswered.

During negotiations to re-open the paper, the government requested that action be taken against some of the paper’s staff members, though what action wasn’t specified, Opondo claimed. “The staff have a right to fear, since The Monitor management agreed to take action–whether that is sacking, demotions, transfers, etc.” In that case, the government has achieved a far more effective means of silencing the paper by targeting individuals with job insecurity, than with a widely covered police raid. The strategy has been used in the past, with at least seven senior managers at The Monitor either thrown out or transferred in the past decade, local journalists said.

The attempts to intimidate critical journalists may have already begun. On June 2, The Monitor‘s sister TV station, NTV, told its outspoken regular panelist, Chris Obure, not to participate in a weekly political talk show. According to Obure, the show’s producer, Michael Baleke, was told by his seniors to keep Obure off the show for an unspecified period of time. “He [Baleke] said he wasn’t given reasons for my not appearing but suspected that management was uneasy,” Obure told me via email. “He also said earlier [before the siege] a government representative had called NTV and warned them about my presence on the show, asking them to reconstitute the panel.” Obure suspects the displeasure is related to his recent comments about discrepancies in army pay and unfair promotions and deployments under Brigadier Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the president’s son.

Also on June 2, The Monitor recalled an early edition of its Sunday paper. The first edition of the Sunday Monitor‘s lead story, “Museveni ranks low in East Africa,” covered the Ugandan president’s poor assessment for governance by the Africa Leadership Index. But Asiimwe ordered editors to drop the story after the early edition had hit the stands and replace it with coverage of a college strike which had originally appeared on page six in the early edition, according to news reports. The Monitor‘s managing director claimed the story had not “been handled well,” the reports said. The story was also removed from The Monitor‘s website.

On the other hand, editions printed since the paper re-opened have also included several columnists criticizing the police raid on The Monitor, as well as sensitive stories such as plans by the outgoing secretary-general to the prime minister’s office to document corruption he witnessed there. Further, because of the prevalence of social media, the scope for censoring stories is diminishing. “We have expanding, alternative spaces which civil society can use to put pressure on the media,” Mwesige said. “In the past, media would have all its pressure from the government, but now we have so many platforms to discuss issues–pressure from civil society will keep the media on its toes in terms of maintaining independence.” Wanyama also believes The Monitor cannot change. “It is the culture of the paper to be critical,” the managing editor said. “If it self-censors, it will cease to be.”