Staying connected in an offline world

By Alexandra Ellerbeck

For Elaine Díaz Rodríguez, founder of Periodismo de Barrio, internet access in poorly connected Cuba comes at a premium. “Our reporters have less than 10 hours a month of internet access,” she told CPJ during the Latin American Studies Association conference in New York, where she was taking advantage of the hotel Wi-Fi. “Between midnight and 3 a.m. every night, I download information off the internet. It’s already part of the professional culture to bring a flash drive back to Cuba.”

Díaz’s experience reflects that of other journalists and bloggers in Cuba who, despite government promises of greater access, said that when they can get online—often in brief spurts and at high prices—they face state monitoring, online harassment and sporadic censorship. Other obstacles include slow connection speeds and limited access points, bloggers and Cuba experts including Larry Press, a professor of information systems at California State University of Dominguez Hills, said.

To get around these challenges, bloggers are using innovative ways to access and distribute content to their offline audience, including through underground computer networks, flash drives and email networks.

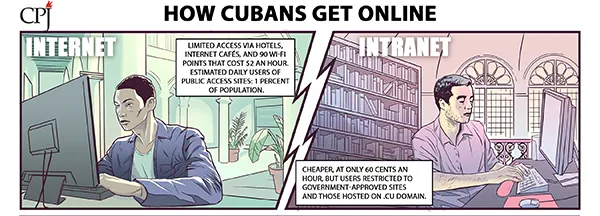

Over the past three years a series of reforms have started to open up the country’s telecommunications sector: the first high-speed fiber optic internet connection, internet access points available, for a fee, to the public, and a new national email system for mobile phones. Last summer, the Cuban government announced the opening of publicly accessible Wi-Fi points, of which there are now 90, according to the country’s sole internet provider ETECSA, which provided an emailed set of responses to CPJ via Cuba’s International Press Center. These are major changes for a country where ownership of home computers was prohibited as recently as 2008.

Despite these moves and government promises, Cuba has one of the lowest rates of internet access in the Western Hemisphere. Figures citing independent estimates and government statistics place it between 5 and 27 percent, but none of the estimates clearly state the methodology for calculating access. In the case of the government statistics, the figure does not differentiate between connecting to the internet and the Cuban intranet, a closed-off network of sites mostly hosted on Cuban domains.

“Given the long-tail effect, the fact is that for everyone who has an internet connection, more than one person is getting online at some point in a given week. What counts? To say that they have access to the internet, what does that really mean?” said Ellery Biddle, a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, and the director of Global Voices Advocacy.

Internet speeds are also poor, with an average download speed of about 1 Mbps, according to the Brookings Institution. In comparison, the United States Federal Communications Commission ruled that internet download speeds in the U.S. must be greater than 25 Mbps to qualify as broadband.

The president of ETECSA, Mayra Arevich Marín said in December 2015 that the number of daily users of the publicly accessible internet points had doubled since 2014. In an interview with the state-run outlet CubaSí, she said there were about 150,000 daily users—a figure that represents approximately 1 percent of Cuba’s population of 11 million.

The government has said that the low level of internet access is a result of the U.S. embargo and the constraints of a developing economy. The government has also said that its strategy is to prioritize the service for public officials, doctors and public points as a means of better distributing a limited resource.

“It is certainly plausible from a development perspective, to concentrate scarce resources on those sectors regarded as social and economic priorities,” Bert Hoffman, head of the Berlin office of the German Institute of Global and Area Studies and an expert on the internet in Cuba, wrote in The Politics of the Internet in Third World Development. “This official line of argument loses credibility to the degree that it is offered not as a complement, but as a negation of the—rather obvious—fact that the prohibition of individual internet access might serve a political function.”

Cuba has always taken a cautious approach to the internet, with Fidel Castro describing it at a rally in 1995 as a new way for the U.S. to impose its ideals “on the world through propaganda and manipulation,” and a military leader the following year describing it as “an invasion not led by marines but by information.”

More recently, Cuban officials have signaled a willingness to embrace technology and expand access, while making clear that it will be on Cuba’s terms. A December 2014 editorial in the state-newspaper Granma read, “Cuba has been, and is, intent upon being connected to the world, despite propaganda to the contrary.” And in July 2015, José Ramón Machado Ventura, the second-highest ranking member of the party, suggested that Cuba had rejected offers to expand internet access for free, to protect the country’s independence. The secretary told the state-owned daily, Juventud Rebelde, “We must have internet, but in our way.”

Miriam Celaya, who writes for 14ymedio, said, “The state owns the media outlets, a monopoly on the press— television, radio, newspapers and so on. For years this was the only ‘truth’ that Cubans heard. Independent journalism, journalism online has the tendency to break this monopoly.” She added, “The changes have come in spite of the government. In the 21st century, there is no way to justify that people don’t have access to internet, so the government has had to open small spaces of access.”

Restraints on access

Cuban law rules that the sole state-run internet provider can “prevent access to sites whose contents are contrary to social interests, ethics and morals.” However, blocking is limited to a handful of prominent sites and many of the sites run by dissidents are accessible, according to journalists with whom CPJ spoke.

14ymedio, the first independent digital news magazine to be based in Cuba, is blocked on the island, although its founder, Yoaní Sánchez, has tweeted that the site is accessible through a proxy server. Boris González Arenas, a journalist and activist, said that the Miami-based site Cubanet has also been blocked at times, and the blogger Taylor Torres said that Cuba Encuentro and Martinoticias are also blocked occasionally.

When Sanchez launched 14ymedio, those trying to access it were re-directed to a site named “yoani$landia” that accused Sánchez of being obsessed with money and said that people were tired of her presenting herself as the “Mother Teresa of Cuban dissidents.” The people behind the redirect site did not identify themselves, but the BBC reported at the time that the site was believed to be run by government officials.

Yuris Nórido, a blogger and journalist, said, “I have access to almost all sites, except 14ymedio. But you would have to ask someone else why that precise site is blocked when it is easy to access much more belligerent sites.”

Although those running Cuba’s more critical outlets face the risk of having websites blocked, the larger concern is having easier and more affordable access to the internet.

“I connect for one hour a day, but that is too expensive. It is $60 a month, which in the Cuban economy is a huge hit,” said Alejandro Rodríguez, who writes on Alejo3399. “But it’s not enough time. It’s nothing. I don’t have time to comment on my blog or post to Twitter.”

The restrictions also mean that despite the rise of independent journalism and blogging in Cuba, there are often more readers outside the country than on the island. “You write a blog and because of the internet situation in Cuba, you’re writing for a very small group of people,” said Torres, who writes about Cuban youth and his personal life on Vísperas.

“In the 21st century there is no way to justify that people don’t have access to internet, so the government has had to open small spaces of access.”

Miriam Celaya, 14ymedio

Luzdely Escobar, a journalist with 14ymedio, added, “The limitations are many because when you are writing an article, you need to be able to pull up information. It’s difficult for us to do daily notes because we often work from archives or documents that we’ve downloaded from whenever we had a chance to connect.” She added, “During a hunger strike by the dissident group Patriotic Union of Cuba in Havana, it was very hard for us to stay informed because information was going around on Facebook and Twitter or on the YouTube channel of the group. We can call using telephones, but the telephones were cut off [for the hunger strikers] and then we didn’t have a way to cover it.”

Díaz said that her team of five reporters use the publicly accessible Wi-Fi points. But, she added, they often plan investigations a year in advance so they can take advantage of the rare chance to travel abroad or have a good connection.

For the majority, the only option is Cuba’s intranet, which allows access to websites that are registered with the .cu domain or are supportive of the country’s government. The ETECSA statement provided to CPJ said that it costs 60 cents per hour to access the intranet at state-run internet cafés, compared to $2 for access to the internet. Some Cubans have free access to it through work, school, or public spaces.

Among these .cu domain names is Reflejos (cubava.cu), a state-run blogging platform that lists about 1,500 blogs and is run by the Youth Club of Computing and Electronics, also known as the Joven Club. Writers have the potential to reach a wider home audience on this platform because it can be accessed whether a reader is connected to the internet or intranet. One of the site’s directors, Kirenia Fagundo García, told Granma, “The only condition is that the bloggers tell the truth about Cuba, without offences, disrespect or denigration.”

Torres, whose blog is not hosted by the platform, said the administrators sometimes remove content that is critical of the government. 14ymedio has also reported that Reflejos removed a blog it had set up on the site, stating that 14ymedio had “repeatedly published information that does not correspond with the objectives for which the Reflejos platform was created.”

CPJ contacted Reflejos and the Joven Club for comment via email, social media and online contact forms, but did not receive a reply.

State monitoring and online harassment

Facing weak legal protections for privacy and internet and cell phone traffic directed through the state-owned internet service provider, many bloggers said they operate under the assumption that they are being watched online.

The use of anonymity and encryption technologies is illegal, according to a 2015 Freedom on the Net report by Freedom House. And, because home connections are authorized for select state employees only, most Cubans have little opportunity to log on from the privacy of their home.

Before obtaining a card that grants online access at public Wi-Fi points or state-run cyber cafés, Cubans must show service providers their identity cards. Norges Rodríguez, who writes about tech issues on the blog Salir a la Manigua, said however, that it is possible to buy temporary cards anonymously on the black market.

The use of Nanostations, a device that helps extend Wi-Fi signals and is also available on the black market, is also spreading, according to Rodríguez, and an article in Cubanet. The device enables Cubans to access a public Wi-Fi signal from home. However, residents would still have to log in through the state-provider and pay a fee, Rodríguez said.

Under a 2008 resolution from the Ministry of Information and Communications, a service provider must record and store internet traffic for at least a year and ensure that users do not use encrypted software or share encrypted files. Web traffic is also routed through the software program Avila Link, which has monitoring capabilities, according to the Freedom on the Net report. Still, several bloggers and journalists said that end-to-end encrypted apps including Facebook messenger and WhatsApp are widely used.

When asked about user privacy, ETECSA said that it “guaranteed the security of [its] networks.” The statement did not include a response to CPJ’s request for comment on state surveillance. The Ministry of Communications did not respond to repeated requests from CPJ for an interview.

The online surveillance tactics mimic the widely reported pervasive offline surveillance in Cuba, where nearly every community has a designated member of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, tasked with reporting unusual or counterrevolutionary activity. Yaima Pardo, a Havana-based filmmaker who has produced documentaries on internet access, discrimination against the elderly, and gay rights, said that state security agents have described her as a traitor in phone calls to her mother.

The blogger and activist Lázaro Yuri Valle Roca said there is a general belief that communications are tapped and he has seen state security agents near his home. Valle Roca added that these agents had asked his neighbors about him. CPJ was unable to independently verify their accounts.

“Although some Cuban internet users surely do worry about electronic surveillance, it is important to recognize that the general expectation of physical surveillance often trumps this concern,” according to Biddle’s research paper for the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Biddle added that many bloggers were open about their identities, seeing this as a form of protection.

Several of the journalists said that they believe the state has the power to intercept communications. When asked whether she thought that her communications were being intercepted, Escobar said, “Totally.” Ted Henken, former president of the non-profit research group Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, said that the national email system available on the state-run phone network was widely believed to be monitored. However, many critical journalists who are often accustomed to offline surveillance, seemed to take monitoring for granted. “This is something that we’ve learned to live with and we don’t have anything to hide,” Escobar said. “Everyone just assumes that it’s natural. I don’t think people really think about it.”

Other critical bloggers have reported being harassed online by trolls who they suspect are organized and encouraged by the state. In 2013, Sánchez posted a video interview with Eliécer Ávila, a former student at the University of Information Sciences, who said he was part of a project known as “Operation Truth.” According to Ávila, as part of the project, which is allegedly associated with the youth wing of the Communist Party, he monitored internet conversations for signs of dissent and wrote rebuttals and comments attacking the reputation of journalists or bloggers who criticized the government. Ávila, who now leads an opposition group called Somos Mas (We Are More), told CPJ that project participants were not paid and that the project has expanded.

When CPJ called the youth wing of the Communist party for comment in August, a representative said he did not know about Operation Truth and asked CPJ to call back at a later date. A university employee, who said he worked in security and protection at the University of Information Sciences, told CPJ he did not know about Operation Truth and because the university was in recess, no one else was available to answer the query.

Reconnecting with the world

Since the restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba, a number of U.S.-based tech companies, including Netflix, Google, and Paypal, have announced plans to open operations on the island. Although Congress has not lifted the embargo, Obama has already removed restrictions on ICT trade with regulation changes in January 2016 and September 2015 that allow exports of telecommunication items and permit U.S. residents to have licensing and marketing agreements in Cuba.

To date, no major deals on internet access between U.S.-based tech companies and the Cuban government have been announced publicly. The only exception, a Google-sponsored center for free public Wi-Fi in the studio of the Cuban artist Kcho, remains more a symbolic gesture than a solution. The partnership, billed as an art museum, has Chromebooks, cardboard virtual reality viewers, and nexus phones, but several bloggers dismissed the project to CPJ, saying that 20 laptops sharing a single Wi-Fi connection is a small gesture in a nation of 11 million who are trying to get online.

Google has not commented in the press on any other projects planned for Cuba beyond saying talks are in “early stages.” Google’s press office did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment.

In January, Daniel Sepulveda, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and U.S. Coordinator for International Communications and Information Policy at the State Department, told OnCuba officials had been reluctant to take up offers for an undersea cable connecting Cuba and the U.S.

The U.S. embargo’s restrictions on banking and money transfers have limited Cubans ability to access some paid internet content and apps. In July, Cuban journalists reported that the Bitly URL shortener had stopped working, leaving hundreds of broken links, after the company transferred to a hosting provider that blocks access in countries under U.S. embargo. Bitly’s chief executive officer said that the company was working with the provider to resume operations.

Cuba has partnerships with some countries. Venezuela financed a roughly $70 million undersea internet cable built between the two countries in 2013 and in January Cuba announced that the Chinese telecoms company Huawei would assist in its effort to expand home broadband.

Huawei has previously been accused of facilitating censorship in Iran, including during the disputed 2009 elections, according to reports. Huawei denied the allegations. The company released a statement in 2011 that said its operations in Iran were no different than its operations in the rest of the world. Doug Madory, director of internet analysis at Dyn, which helps companies manage internet infrastructure, said he thinks Huawei was chosen because it was inexpensive and non-Western. He said that Cuban authorities had worked with the company previously and noted that a number of Western and U.S.-based companies also sell surveillance and censorship to foreign governments.

Circumventing the web

Despite facing many obstacles, Cuba’s journalists and bloggers have found innovative ways to distribute content, including using flash drives and underground computer networks, and sending articles via the state email system.

“I distribute through flash drives and CDs. Sometimes I give it to friends who help distribute,” said the filmmaker Pardo, when asked how she got her films into the hands of Cubans. “Sometimes when we go to rural areas, people have already seen my film.”

The Packet is another way Cubans share and access media. A terabyte of documents, websites, movies, YouTube videos, books and TV shows is downloaded each month on to hard drives and flash drives, and distributed across the country. A survey cited in the state-run Cubadebate in October 2015 found that about 39 percent of people in Havana access the downloaded content, although the author of the study described the number as conservative. The Packet’s reach is probably why the producers of TV series “Game of Thrones” found a strong fan base when they visited Havana last year. One of the distributors told The Wall Street Journal that interest in the HBO show and similar entertainment content was high among his customers.

The Packet offers an opportunity to reach a wider audience. It often carries content from state-owned news sites, as well as from OnCuba and foreign news sites. Political writing and reports from independent outlets associated with the Cuban opposition usually don’t make their way in. “There’s not much journalism in The Packet, but every now and then you’ll see it,” said Alejandro Rodríguez.

Escobar, from 14ymedio, said that the outlet’s journalists get around their site being blocked by distributing content in other formats. “We have a PDF that gets sent around and people download and pass around on flash drives,” she said. “We have an email bulletin that goes out to thousands of subscribers a few times a week.”

Another option is Street Net, a more than eight-year-old underground network of about 9,000 computers in Havana that are used to share files, games and videos, and to chat. Authorities have forced similar networks to close. In 2012, Granma reported on a government investigation into an illegal telecoms network, and in 2014, the Miami Herald wrote about a crackdown on a network of 120 users. The team behind Street Net said they have a policy of avoiding anything that could set off the censors, including political content, which often restricts independent journalism, according to a report on the website Gizmodo.

The off-line distribution may be a stopgap solution, but it is one that has enabled a generation of Cubans to talk and listen to the outside world. As an editorial in the independent tech website Cachivache Media said, “The idea of a Cuba, blind and deaf, that is waiting to discover and be discovered by the rest of the world, is far from being real.”