Introduction

By Bob Dietz

At least 42 journalists have been killed—23 of them murdered—in direct relation to their work in Pakistan in the past decade, CPJ research shows. Not one murder since 2003 has been solved, not a single conviction won. Despite repeated demands from Pakistani and international journalist organizations, not one of these crimes has even been put to a credible trial.

This perfect record of impunity has fostered an increasingly violent climate for journalists. Fatalities have risen significantly in the past five years, and today, Pakistan consistently ranks among the deadliest countries in the world for the press.

ROOTS OF IMPUNITY

• Table of Contents

Video

Roots of Impunity

In print

• Download the pdf

In other languages

• اردو (pdf)

The violence comes in the context of a government’s struggle to deliver basic human rights to all citizens. The independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan laid it out succinctly when it said in its annual report in March 2012 that “militancy, growing lawlessness, and ethnic, sectarian and political violence exposed the government’s inability to ensure security and law and order for people in large parts of the country.”

It is in this environment that reporter Elizabeth Rubin investigated the targeted killings of two journalists—Wali Khan Babar in Karachi and Mukarram Khan Aatif in the tribal areas—along with the underlying culture of manipulation, intimidation, and retribution that has led to so many other killings. Her reporting found:

- An array of threatening actors that includes not only militants, criminals, and warlords, but also political, military, and intelligence operatives.

- A weak civilian government that acquiesces to the will of the intelligence services, the army, and criminal elements in the political parties.

- Intelligence services that aggressively pursue a political agenda; that pressure, manipulate, and intimidate news media; and that, at times, collaborate with or enable the Taliban and other militants.

- A criminal justice system that is weak and lacks independence, leaving it vulnerable to political pressure.

- Police who are insufficiently trained in such fundamental areas as forensics and security.

- Government officials who, in a climate of widespread impunity, feel free to intimidate journalists.

And news media that, while free and robust, are also manipulated by the intelligence services, the military, and the political parties.

“It’s rough out there,” Najam Sethi told CPJ. Sethi, longtime editor of The Friday Times and host of a popular Urdu-language political program on Geo TV, and Jugnu Mohsin, his wife and fellow journalist, have lived under intense threat for years. “One never knows whether the Taliban is gunning for you or whether the agencies are gunning for you,” said Sethi, who is based in Lahore. “And sometimes you don’t know because one is operating at the behest of the other.”

Sethi, a strong critic of militant groups, is equally as critical of the government, the military, and the country’s intelligence agencies. In the Federally Administered Tribal Areas along the border with Afghanistan, where Aatif was killed, the threatening actors include the military and intelligence services, militants, weapons and drug traders, and various warlord groups that the government plays against one another. The nation’s largest city, Karachi, where Babar was murdered, is a combat zone of political parties fighting for turf, militant groups establishing rear-echelon redoubts, and criminal gangs hungering for profit. At least three journalists have been killed in Karachi because of their work in the past decade.

The intelligence services feel free to pursue their own political agendas; their actions are partly the cause and partly the result of the nationwide free-for-all of violence. The military, which has taken power three times since the country’s founding in 1947, brooks little criticism and never hesitates to threaten journalists who dare to speak out. Government, military, and intelligence officials are suspected of involvement in at least seven journalist murders in the past decade, CPJ research shows. Weak civilian governments have wielded little control over them.

Working in this milieu are news media surprisingly free and robust. An explosion of private cable television broadcasters that began under Gen. Pervez Musharraf has resulted in more than 90 stations today. Print and radio outlets thrive. But journalists also say that media outlets are manipulated by the military and intelligence services, and that news organizations have not met the escalating risks with commensurate security and training measures. In recent years, the industry’s news managers have undertaken several sincere attempts to raise the quality and security of Pakistani media. Most admit it is still a work in progress.

In May 2011, a CPJ delegation met with President Asif Ali Zardari and several cabinet members. At that meeting, the president pledged to address the country’s record of impunity in anti-press violence. In fact, nothing substantial was undertaken, and the record has only worsened. In most cases documented by CPJ, little has been done beyond the filing of a preliminary police report. In 2012, when the United Nations’ educational wing, UNESCO, drafted a plan to combat impunity in journalist murders worldwide, Pakistan lobbied furiously, if unsuccessfully, to have it derailed. A senior Pakistani official told CPJ at the time that it would be “unfair to say outrightly that Pakistan has a high rate of unresolved cases.” The facts—23 murders, all unsolved—show otherwise. The president’s office did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment on the findings of this report.

Pakistan’s leaders are not meeting their obligation to guarantee the rule of law and fundamental human rights. The newly elected government owes its citizens a criminal justice system that is independent, its investigators and prosecutors sufficiently supported with staff and resources to bring about successful prosecutions. Many journalist murders go unprosecuted because of intimidation, interference, or worse from political parties, the military, and the intelligence services. That must end.

Given the breakdowns, Pakistani journalists have begun addressing the problems on their own. Larger media houses are strengthening training and security. Some are setting out guidelines for ethical conduct. Journalists are drawing on a long heritage of professional solidarity to speak against anti-press harassment.

As one of the nation’s strongest democratic institutions—and one of its most imperiled—the press has both the ability and the urgent need to find effective solutions.

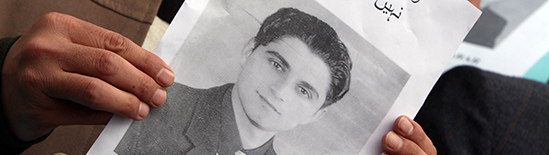

(Photo by AP)