In March, 2020, Turkey’s Constitutional Court issued an unexpected decision, overruling a local court that blocked a news website in 2015, according to news reports. But the editor who filed the appeal with the court remains unhappy, he told CPJ via WhatsApp, because the original website remains inaccessible in Turkey — along with the 62 replacements that were blocked, one by one, ever since.

The editor, Ali Ergin Demirhan, is one of several journalists in Turkey engaged in a protracted game of whack-a-mole with the Turkish judiciary. Turkey’s courts routinely block news sites, and the outlets bounce back with new addresses, often the name of the publication with a new number attached. Demirhan’s website, the left-leaning outlet Sendika, is now available at sendika63.org.

Turkey’s Law No. 5651 authorizes courts to order domestic internet service providers to block access to links, including to websites, articles, or social media posts. Passed in 2007, the law is meant to take aim at child pornography, online gambling, and disparaging material about founder of modern Turkey Kemal Atatürk, among other things, but, as CPJ has documented, it is often used as a potent censorship tool. (The law is just one way that Turkey censors online content. YouTube, Wikipedia, and Twitter have been intermittently banned and then reinstated in recent years, often over content deemed anti-government or dangerous to public security.)

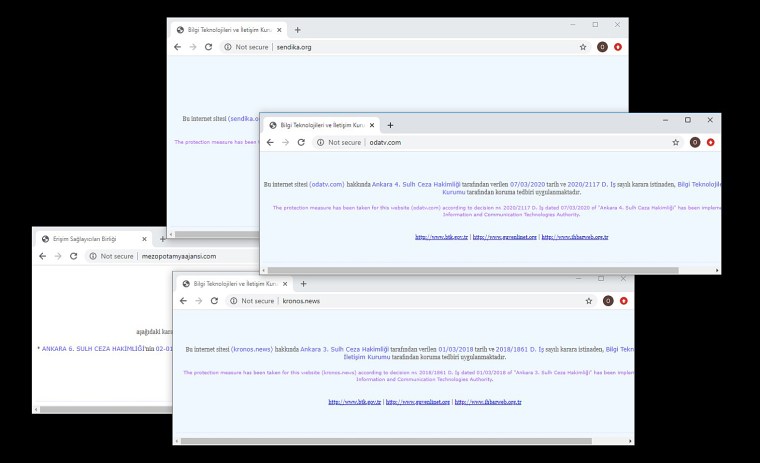

Most blockage requests are made by the government via the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK), but individuals and other government agencies may make such requests of Turkish courts, according to a 2020 report on the issue by the local Freedom of Expression Association (İFÖD). BTK did not reply to a request for comment from CPJ.

Between 2014 and 2019, Turkish courts ordered internet providers to block 408,494 URLs, though it is not clear how many host independent reporting, İFÖD reports. But, as Demirhan and three other editors told CPJ via email, Turkey’s independent online media remains dogged in the face of the blocks; some sites even buy domain names in bulk so they can quickly relaunch with a slightly different moniker.

Mezopotamya editor Ferhat Çelik told CPJ that his site, which is pro-Kurdish, has been blocked 25 times since 2018. Kronos editor Doğan Ertuğrul said his has been blocked 33 times since 2018. (Kronos’ staff is in exile; the journalists previously worked at outlets associated with Fethullah Gülen, the self-exiled cleric whose movement Turkey deemed a terrorist group.) Odatv editor Furkan Karabay said his site, a left-leaning nationalist outlet, has only recently been hit with blocks — four of them since March of this year. The censorship started after three employees were arrested for allegedly exposing the identity of a Turkish intelligence officer killed in Libya, as CPJ documented. These editors, along with Sendika’s Demirhan said there is no line of communication with the authorities who authorized the blocks, leaving them in the dark about why the sites were shut down.

Why does the Turkish government insist on this practice when the websites almost immediately pop back up? Erkan Saka, a media studies professor at Istanbul Bilgi University, named two reasons. “One includes a militaristic metaphor: It is a kind of ‘war of attrition,’” he told CPJ in an email. “The government knows that these are relatively small-budgeted media organizations. They have very limited sources, monetary-wise or personnel-wise. Every blockage forces these media companies to open up new domain names, to make necessary technical decisions.” The second reason, he said, is that “every time a domain name changes, despite all diverting techniques, a site loses traffic, loses some of its news links, etc.” In effect, the “sites’ voices are explicitly limited by changing URL names continuously.”

Demirhan’s experience at Sendika seems to bear these observations out. Every time the site relaunches, he has to expend effort reorienting readers to the new URL, usually by announcing it on social media or relying on other outlets to publish it. Getting Sendika’s journalism to continue to appear in search results has proven complicated. With each relaunch he must ask Google to categorize the new address as a news site, otherwise its links won’t show up in Google News or the “top stories” section of the Google homepage. Demirhan claims that after the fifth relaunch, Google stopped responding to his requests. (CPJ’s email to Google’s press office for comment went unanswered.) The result, said Demirhan, is that Sendika has been “pushed back in the race for the reader.” In the past, some 300,000 visitors frequented Sendika per day, but after the blocks, traffic has decreased to around 300,000 visitors per month, he said. Çelik and Karabay also spoke of similar traffic slowdowns at Mezopotamya and Odatv.

Traffic aside, the blocks have chipped away at Sendika’s reputation among readers. Frequently shut down outlets are seen as “risky,” so readers avoid sharing their links on social media, Demirhan told CPJ, and sources sometimes avoid speaking to his reporters. Ertuğrul, of Kronos, had a similar take: “Visiting a website which the government blocked so many times, leaving such a digital trace, is considered an adventurous move for a lot of people.”

To lift a block, a news outlet may appeal to a local court; if that fails it can appeal to the Constitutional Court of Turkey; and if that fails it may bring its case to the European Court of Human Rights, Demirhan explained. According to Karabay, who has appealed all four blocks of Odatv, the Constitutional Court sometimes takes up to five years to hear cases.

While Demirhan has gone through the trouble of appealing each block against Sendika, he considers his recent win — for which he said the court awarded him 6,000 Turkish liras (US$820) — very unusual. Other editors told CPJ they don’t see the point of appealing. “We did not do it considering the trials would take too long and maybe the website will be blocked several times more during that period and each appeal would bring a financial cost,” Çelik, the editor of Mezopotamya said. Ertuğrul of Kronos said he wanted to launch an appeal but the site’s lawyer told him there was “no chance” that it would succeed given that Ertuğrul and the other editors are wanted in Turkey for their alleged membership in the Gülen movement. “Therefore, we did not take legal action,” he said.

One way to get around the blocks, Karabay said, is to self-censor. “You are not only blocked but being made a target at the same time. Because of this, self-censoring is practiced out of necessity.” But Demirhan refused to entertain this as a solution, arguing that it wouldn’t work anyway. “The reason for the blocking is not a certain [piece of] content, it is the general editorial policy, the existence of the website itself.”

CPJ researcher Hakkı Özdal contributed to this report.