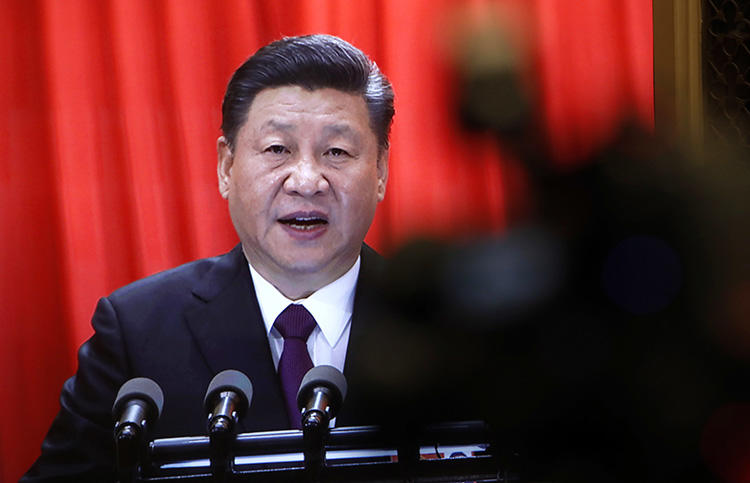

Hours after the Chinese Communist Party proposed a constitutional change last month to lift presidential term limits, any words or phrases that remotely suggested President Xi Jingping was seeking a life term were blocked from social media. Censors targeted everything from “Emperor Xi,” “The Emperor’s Dream,” and “Dream of Returning to the Great Qing,” to “Winnie the Pooh,” a reference to Xi’s apparent resemblance to the cartoon character, the China Digital Times reported.

Such censorship is not new in China, but in recent months the country has increased its grip, regulating tools such as virtual private networks (VPNs) that can bypass the country’s infamous firewall, issuing lists “of “approved” news outlets, and disbarring lawyers who represent jailed journalists.

On January 30, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced a list of 462 websites and social media handles granted permission to provide online news services. Outlets that create a news website without permission face a fine of up to 30,000 Chinese yuan (US$4,700). The following month, the administration announced regulations for social media users that will legally require users to disclose their name, personal ID, organization code, and phone number before being allowed to post content online. The new regulations come in effect March 20.

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology also announced that from March 31 it will regulate unlicensed VPNs to “maintain a fair, organized market order.” The move means that individuals and foreign companies whose operations require the use of VPNs will only have access to state-approved VPNs.

A veteran reporter for an English-language media outlet told CPJ that VPNs are crucial to their reporting in China. Without them, the reporter said, they would not feel safe to file stories and pictures or to communicate with editors, colleagues, and interviewees.

This is not the first time authorities have attempted to regulate circumvention tools or social media. Pu Fei, a volunteer at human rights news website 64 Tianwang, told CPJ that since 2016, most of the site’s volunteers found they were blocked from opening Weibo accounts when they tried to register using their ID.

As well as attempts to regulate and censor social media platforms, authorities appear to be using the technology to track journalists.

The reporter, who asked to remain anonymous because the outlet for which they work has a strict interview policy, told CPJ they believe their WeChat messages are being watched. “In more hostile circumstances, my WeChat account has been forcefully logged out, and I was banned from using my WeChat account for over a week,” the journalist said. “As for Weibo, my private message function might have been permanently disabled or filtered.”

The reporter added that they believe officials accessed their WeChat account to surveil the journalist. The reporter said that after using WeChat to discuss visiting a friend in another city, local community officers approached the friend’s family and warned them not to let the journalist stay. The reporter told CPJ the officers had their full name and the name of their news outlet.

The impact of such surveillance means that reporters are becoming more reluctant to use WeChat and Sina Weibo.

“It makes China reporting very costly, in terms of manpower investment as well as security measures,” the journalist said. “It would also greatly endanger the safety of my interviewee. But it doesn’t mean we can stop doing it just because it’s hard. It calls [for] more professional, creative and persistent reporting.”

China’s crackdown is not just confined to the internet and social media. Earlier this month, police in Beijing detained French journalist Heike Schmidt, the China correspondent for the French Foreign Ministry-funded outlet, Radio France Internationale, for about an hour and confiscated her voice recorder, the journalist told CPJ. Schmidt said she was stopped and questioned after interviewing people in a mall about the constitutional vote.

While international journalists are more likely to be deported than detained for a long period, local journalists or media sources–along with their families and the lawyers–face greater risks.

CPJ documented in January how the wife of Chinese American journalist Chen Xiaoping disappeared from her home in Guangzhou city, apparently taken by authorities in retaliation for Chen’s reporting. And on February 10, police detained Xu Qin, an independent human rights researcher whom news agencies rely on as a source, according to Radio Free Asia. Xu’s arrest came just days after Radio Free Asia interviewed her about the detention of Sun Lin, a journalist jailed for reposting articles critical of the Communist Party, according to a detention notice officials provided to Xu’s family. Both are still in custody, according to reports.

Lawyers representing jailed journalists and critics also face harassment. On February 12, the Guangdong Department of Justice disbarred Sui Muqing, the lawyer who represented Huang Qi, the publisher of human rights news website 64 Tianwang. A notice from the Guangdong Department of Justice, sent to the lawyer, said he was disbarred for “using uncivilized, offensive wording” and other poor behavior while representing a fellow lawyer, and for bringing cell phone to take photos of a rights activist in a detention center whom Sui was representing.

Sui told CPJ he believes his disbarment will intimidate other lawyers into not representing human rights activists or people charged with political crimes. “Although there will still be lawyers brave enough to take on rights cases the flexibility of what lawyers can say and how they handle these cases will be very confined,” said Sui.

Lin Qilei, a lawyer who represented jailed journalist Wang Shurong, told CPJ that he feels the pressure after Sui’s disbarment, but is mentally prepared for anything that could happen, including jail. “I think, as a lawyer, my duty is to defend for my clients. Most of my clients are persecuted for defending public interests or speaking out about social issues. I admire them,” Lin said.