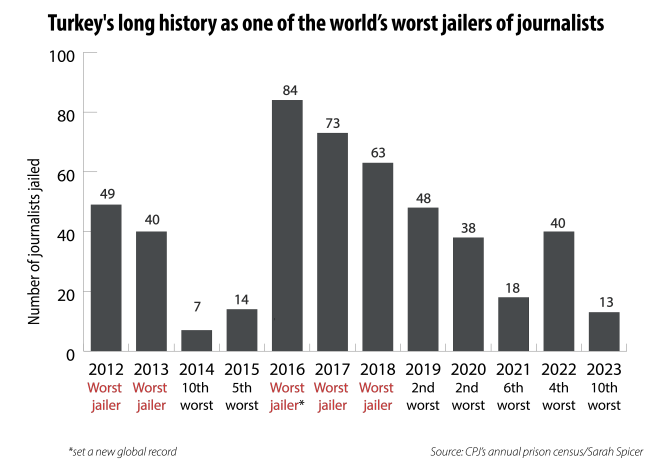

In CPJ’s 2023 annual prison census, Turkey was the world’s 10th worst jailer of journalists—its most press-friendly ranking in almost a decade—with 13 behind bars, down from 40 the previous year.

But the latest numbers don’t tell the full story. Turkey has consistently vied with China for the top slot in CPJ’s list of shame and has taken first place five times in recent years, in 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, and 2018.

The fall in imprisoned journalists in Turkey does not signal an improvement in media freedom, Barış Altıntaş, co-director of the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA), a local group advocating for press freedom and freedom of speech, told CPJ.

“Even if there were zero journalists in prison today, 200 journalists may be arrested tomorrow,” she said. “The government determines the number of arrested journalists, even when it is low.”

Although dozens of journalists have been freed since 2022, most are still under investigation or awaiting trial, placing a stranglehold on the country’s critical media, CPJ’s research shows.

Why is Turkey—a NATO member with close ties to the West—frequently ranked alongside authoritarian states like Iran and Egypt in CPJ’s prison census?

Understanding Turkey’s high rates of incarceration of journalists requires a closer look at its domestic politics, particularly the long-running conflict with Kurdish insurgents.

Imprisoned due to political winds

The reasons that journalists are imprisoned in Turkey are “100% political,” said Ülkü Şahin, a lawyer with the Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS), who monitors media trials. “The arrests of journalists run in parallel with politics in Turkey. Whenever there are times of crisis in Turkey, the number of arrested journalists increases.”

The conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has ruled Turkey since 2002, has repeatedly used the security forces and judicial system to outmaneuver its political opponents.

“The journalism trials all stem from politics,” one court reporter told CPJ on condition of anonymity, citing fear of reprisal. “The judges are either ignorant about the law or they manipulate it for their advantage.”

Shifting political winds in Turkey regularly sweep up journalists across the political spectrum. Left-wing nationalist journalists were targeted in the early 2010s, when hundreds including lawmakers, retired generals, and academics were arrested in relation to the alleged ultra-nationalist Ergenekon conspiracy to overthrow the government.

Some jailed reporters were linked to coup plots, while others were arrested for “influencing a fair trial”—effectively criminalized for independent coverage of police and court activities. Journalists who had been close to the previous regime were imprisoned alongside Kurdish citizens and socialists, two groups that are always present in the country’s prisons.

Today, Turkey’s three longest-serving journalists are socialists serving life sentences. Hatice Duman has been behind bars since 2003, Mustafa Gök since 2004, and Erdal Süsem since 2010.

In 2016, the trend of politically-influenced media arrests continued with the mass detention of journalists working for outlets associated with the U.S.-based Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen, after his religious group fell out with its former ally the AKP.

Media detentions intensified after the 2016 attempted military coup, which President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blamed on Gülen, who denied involvement. That year, Turkey set a new global record of 84 journalists in jail—the most ever imprisoned by a nation in a year in CPJ’s census.

‘We will punish you through the judiciary’

Today, the government continues to pressure the media to report its version of reality, a second court reporter told CPJ on condition of anonymity, citing fear of reprisal, adding that the arbitrary sentences handed down to journalists were the “best indicator of how the judiciary is under the influence of politics.”

The government’s attitude has been “either you practice journalism according to our instructions or we will punish you through the judiciary, with either investigations or prison,” said Fatma Demirelli, co-director of Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), a local press freedom group.

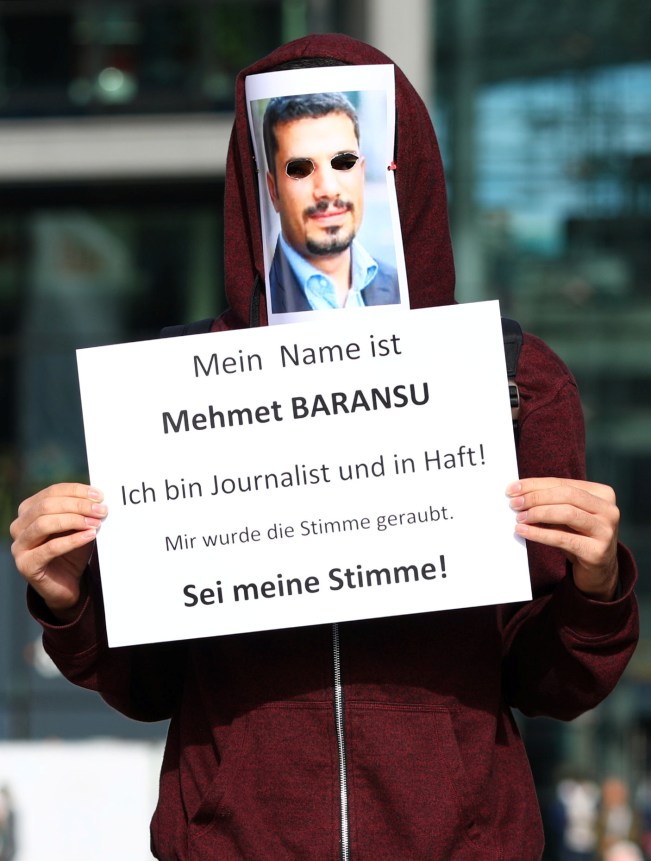

Mehmet Baransu, a former reporter and columnist for the shuttered newspaper Taraf, has been imprisoned since 2015 on multiple charges that stemmed from his reporting. In 2020, he was sentenced to more than 19 years in prison on charges that include alleged membership in Gülen’s movement. The government considers Taraf a mouthpiece for the Gülen movement, which it has designed as a terrorist organization and refers to as FETÖ/PDY.

Baransu has appealed the verdict. After the 2016 coup attempt, thousands of people with suspected ties to the Gülen community were interrogated but “there wasn’t one testimony regarding my or Taraf’s involvement [with Gülen],” Baransu told CPJ in an interview conducted via his lawyer.

Meanwhile, he remains in prison awaiting retrial on two cases which have been merged. One charge relates to a leaked National Security Council document that Taraf published and the other charge, which the journalist denies, is that he obtained a classified military document titled “The Sovereign Action Plan.”

Baransu believes the multiple journalism-related charges that he is facing are a punishment for his 2010 scoop about a planned coup. These reports, based on leaked documents and published in Taraf in 2010, led to the so-called Sledgehammer trials, in which more than 300 military officers were jailed.

Kurdish journalists labeled as terrorists

Kurdish journalists in particular are in the crosshairs. The question of Kurdish self-determination is a live one in Turkey, where Kurdish people have been subjected to decades of discrimination since the country’s founding. Turkish security forces have been fighting the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) since 1984 and peace efforts in the early 2010s failed. The PKK is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and many Western governments.

Vaguely worded anti-terror and penal code statutes have allowed authorities to conflate journalistic reporting that they consider favorable to banned groups, like the PKK, with membership of a terrorist organization—for which the punishment is up to 15 years in prison.

Journalists’ union lawyer Şahin described terrorism-related charges as a “very functional” offense for authorities because of their “flexible” legal definition. Instead of asking prosecutors for evidence of a defendant’s “organic ties” or links to a terrorist organization, courts punish journalists simply for reporting the news, Şahin said.

Four out of five of the newly jailed journalists named in CPJ’s 2023 prison census were Kurdish— Sedat Yılmaz, Abdurrahman Gök, and Dicle Müftüoğlu were arrested over alleged PKK ties. Meanwhile, Celalettin Can was serving a 15-month sentence for guest editing the pro-Kurdish newspaper Özgür Gündem for one day in 2016 before it was shuttered due to alleged PKK ties.

(CPJ’s prison census provides a snapshot of journalists jailed as of December 1; since then, some Turkish reporters have been released. Gök and Yılmaz were freed pending trial on December 5 and 14 respectively, while Can was released conditionally on December 20.)

‘Revolving door’ of arrests and intimidation

When it comes to the Kurdish media, Turkey has an unofficial revolving door policy: as soon as one journalist from a newsroom is released pending trial, another is arrested, said Serdar Altan, one of 15 Kurdish members of the press — 14 journalists plus one media worker — imprisoned in June 2022 on charges of PKK membership.

This is an intimidation tactic, said Altan, who was freed on bail, after 13 months behind bars, on July 12, the day that the group’s mass trial on terrorism charges opened.

Sometimes the aim is to hinder an outlet’s work, at other times it’s to make an example of the journalists, but authorities generally avoid arresting every journalist at an outlet or shuttering it to avoid “negative publicity,” he said.

The main reason that the number of Turkish journalists in jail dropped in CPJ’s 2023 census is that a mass group that was imprisoned as of CPJ’s census date in 2022 had been released, awaiting trial, on that same date in 2023.

All were indicted on charges of terrorism, with their outlets labeled as propaganda tools because of their news policies, according to CPJ’s review of indictments, verdicts, and interrogation records.

CPJ visited the mainly Kurdish city of Diyarbakır, in southeastern Turkey, to observe several of these trials on terrorism charges in 2023. The courthouse had the usual harsh, white florescent lighting seen in similar buildings across Turkey, but security was noticeably tighter: two X-ray searches, full height turnstiles, an ID control, a ban on phones in the courtroom.

Journalists’ trials in this part of the country usually do not attract much public attention in western Turkey because the government is “effective” in presenting them as cases involving terrorist propaganda, said Altan, who is based in Diyarbakır.

“The Western media says, ‘Let’s not get into this if they took the journalist because of terrorism,’” he said.

Altan co-chairs the Dicle Fırat Journalists Association, a local press freedom group. His other co-chair, Dicle Müftüoğlu, is being held on terrorism charges in Sincan Women’s Closed Prison in the capital, Ankara. When her trial opened in Diyarbakır on December 7, she participated via teleconference.

Yılmaz—who worked with Müftüoğlu as an editor at the pro-Kurdish Mezopotamya News Agency—agreed that Turkish civil society was often reluctant to stand up for Kurdish journalists.

“Being a Kurdish journalist is perceived as a potential crime in the polarized, divided circumstances of Turkey,” said Yılmaz, who spent eight months in detention prior to his December 14 release on the first day of his trial on terrorism charges.

“Being a Kurdish journalist makes your non-existent crime even heavier.”