CPJ’s global campaign to free the press

CPJ believes all journalists should be able to report freely, without any fear of harassment or retaliation. But each day, all over the world, reporters, photographers, editors, and bloggers are imprisoned for their work. In December, CPJ published its annual prison census, which found that at least 262 journalists were behind bars, the highest number we have ever documented.

CPJ can work for years in some cases to win the release of journalists imprisoned for their work. We meet with government leaders, and we support many of our imprisoned colleagues through our Journalist Assistance program. We also conduct campaigns calling for their release. In 2017, CPJ launched its Free the Press campaign to raise awareness and take action around the cases of journalists imprisoned on anti-state charges. In 2017, CPJ found nearly three-quarters of the 262 journalists behind bars were jailed on these allegations. We’ll be launching another campaign in the spring.

In 2017, CPJ advocacy helped secure the early release from prison of 70 journalists, the highest figure since 2009, when we began keeping records. And since January, we have helped win the early release of at least 21 journalists. This is a combination of our increased advocacy efforts and campaigns, as well as our high-level meetings, research, and outreach. The number is also a result of a negative trend–more journalists are being jailed worldwide, as is evident from our annual prison census, which shows the number of journalists in prison has increased in recent years.

While our efforts don’t often lead to the immediate release of journalists, they do help put pressure on the governments jailing journalists. Governments trying to change their international perception know they can improve their image by releasing journalists behind bars. This is especially true for three countries–Ethiopia, Uzbekistan, and Cameroon–which released a flurry of journalists in the past year.

Ethiopia

In CPJ’s 2017 prison census, we documented the imprisonment of at least five journalists in Ethiopia: Darsema Sori, Eskinder Nega, Khalid Mohammed, Woubshet Taye, and Zelalem Workagegnehu.

Radio journalists Darsema and Khalid were arrested in early 2015 and sentenced to prison on charges including planning to overthrow the government. Zelalem, a reporter, was arrested and charged under the country’s 2009 anti-terrorism law. In 2016, he was sentenced to more than five years in prison. Columnist Eskinder was behind bars since 2011. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison on vague terrorism charges. Editor Woubshet was also jailed since 2011, after he published a column critical of the ruling party’s performance in its two decades of rule.

CPJ condemned the journalists’ imprisonments and worked to raise awareness of their cases. We published stories on them and called repeatedly on Ethiopian authorities to release them. In 2012, a CPJ delegation to Ethiopia urged high-level government officials to release all journalists imprisoned in the country. We also included details of the journalists in every prison census CPJ published since their arrests.

In January, after the Ethiopian government announced plans to release hundreds of prisoners, Darsema, Khaled, and Zelalem were freed. In early February, Ethiopia announced it would pardon 746 more prisoners. Less than a week later, Eskinder and Woubshet were released.

Today, every journalist CPJ documented behind bars in Ethiopia in late 2017 is free.

Uzbekistan

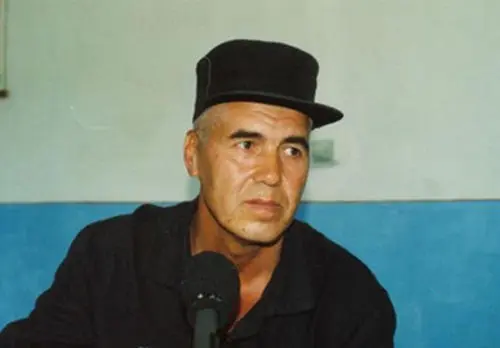

CPJ’s efforts were never more necessary than in the cases of Yusuf Ruzimuradov and Muhammad Bekjanov, two of the longest-jailed journalists in the world.

The journalists of the opposition newspaper Erk were convicted in Uzbekistan in 1999 of publishing and distributing a banned newspaper. Ruzimuradov was sentenced to 15 years in prison; Bekjanov, to 14 years, though both their sentences were later increased. CPJ repeatedly urged authorities to release them in alerts, blogs, and letters and launched campaigns calling for their release. We also included both of them in our annual prison census each year since their imprisonment.

In 2016, Shavkat Mirzyoyev became the president of Uzbekistan after Islam Karimov’s death. Early in 2017, Bekjanov was released from prison. He had spent 18 years behind bars. Then, just a few weeks ago, authorities also freed Ruzimuradov after nearly 19 years in prison.

Cameroon

Cameroonian authorities often arrest journalists under its 2014 anti-terror law. While the legislation is part of an effort to counter attacks by the extremist group Boko Haram, CPJ has found authorities use it to silence the government’s critics.

This is especially true in the case of Cameroonian journalist Ahmed Abba, who reported on attacks by Boko Haram and refugee issues for Radio France Internationale’s Hausa service. Abba was arrested in July 2015 and questioned about the militant group’s activities. In April 2017, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

CPJ advocated for Abba’s release. We published alerts and statements as well as an open letter to Cameroonian President Paul Biya that called for his freedom. We wrote an op-ed in the South African paper Daily Maverick and included him in our Free the Press campaign. We included details of his case in a report published in September, called “Journalists Not Terrorists,” on Cameroon’s use of an anti-terror law to arrest journalists. We honored Abba with CPJ’s 2017 International Press Freedom Award. Throughout, we met with African, U.S., and EU leaders to urge them to call for his freedom.

Then, in December, Abba was released from prison.

But Abba was not the only journalist imprisoned in Cameroon last year. In early 2017, at least three Cameroonian journalists were arrested under the anti-terror law for their work. CPJ published stories about their arrests and called for their immediate release. In September, they were freed. In December, Patrice Nganang, a Cameroonian-American academic and columnist, was detained on allegations of offending the president in a Facebook post. CPJ published a statement about his detention. In late December, he was released.

CPJ welcomes Program Director Carlos Martínez de la Serna

In February, CPJ welcomed Carlos Martínez de la Serna as its new program director. Here, Martínez de la Serna, who oversees CPJ’s programmatic work from New York, talks about what attracted him to CPJ and how he plans to use his background in journalism and digital innovation to enhance our work.

What originally drew you to CPJ?

I’d have to say it would be CPJ’s commitment to promote press freedom worldwide–and its consistency through the years in pursuing its mission. This is a critical moment for independent media and, after two decades of working in journalism and technology, I want to be a part of CPJ’s efforts in defending the rights of journalists to do their work.

You have a background in journalism. Tell us a little bit more about that.

During my career as a journalist, I’ve been interested in creating new tools and efforts to support and advance journalism in the digital age. I’ve been a reporter, but I’ve also been involved in managing teams, launching new initiatives, and exploring new ways to use tech, advocacy, and research. I learned so much from being involved in launching new ventures–I was a co-founder of the research and journalism nonprofit organization porCausa, and I’m still involved with it as a board member.

How do you see this influencing your work for CPJ?

My experience as a journalist working in different countries has greatly shaped my understanding of the essential role of an independent media in empowering individuals and in fostering civic, political, and social life. This is the background and the mindset that, I believe, I am bringing to this role.

How do you see yourself helping in CPJ’s mission to promote press freedom?

This is not the best time for press freedom. Old methods to silence reporters now coexist with new ones. We are at a critical point and must think through these issues in the larger context of defending press freedom and advocating on behalf of journalists. I’m very interested in contributing to this conversation and in supporting CPJ’s research across regions, documenting the conditions for journalism in an ever-evolving environment.

Welcome to New York! What’s your favorite thing about the city?

I love the city. I’ve lived in different places in the United States and in other countries, and here I feel at home. I’m looking forward to enjoying New York’s cultural and social life with my family–hopefully, I’ll also have an opportunity from time to time to attend a jazz concert, one of my passions.

Must-reads in February

In late February, Slovak investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his girlfriend were found shot dead in his house. The journalist wrote investigative stories, most recently looking at suspected tax fraud linked to a luxury apartment complex. “This killing is a grim reminder that when journalists are threatened because of their work, the threats must be taken seriously,” CPJ’s deputy executive director, Robert Mahoney, said.

CPJ’s senior Southeast Asia representative, Shawn Crispin, wrote in February about how Myanmar’s foreign and local media are under heavy assault. “Nowhere is this more apparent than in the continued detention of Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo,” who have been charged under the country’s colonial-era Official Secrets Act, Crispin said.

In February, Venezuela’s new anti-hate law was enforced against a local paper that published a column warning an economic meltdown could be dire for the country. The Maduro government, CPJ’s Andes correspondent John Otis wrote, “already has numerous tools to control and intimidate the media … now, it has another intimidating tool.”

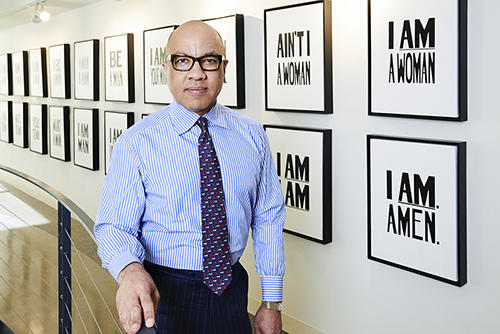

Ford Foundation’s Darren Walker joins CPJ’s board of directors

In February, CPJ welcomed Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, to our board of directors.

“It’s a challenging time for the journalists on the front lines who so often give voice to those with little power,” Walker said, “and I am inspired to serve on this board at a time when CPJ’s mission is more important than ever.”

At Ford, Walker oversees a $13 billion endowment and $600 million in annual grant making and charitable activities. Prior to joining Ford, he was vice president at the Rockefeller Foundation.

“We are delighted that a leader of Darren Walker’s caliber is joining the CPJ board at a time when threats against journalists and a free press have never been greater,” said CPJ Board Chair Kathleen Carroll.

Upcoming events

On March 14, CPJ is joining with Reporters Without Borders, Article 19, and the International Women’s Media Foundation, as well as the Permanent Missions to the U.N. of France, Greece, and Lithuania to sponsor a panel on the safety of women journalists. The missions are participating on behalf of the Group of Friends on the Protection of Journalists, whose members include 19 countries.

The panel will include discussion of how states can effectively combat the violence and dangers that face women journalists.

Read more about the event here.

CPJ in the news

“With the press under attack–literally, in many places–who’s coming to its defense?,” Inside Philanthropy

“2017 was the most dangerous year ever for journalists. 2018 might be even worse,” The Washington Post

“It’s the end of the world desk as we know it,” The Nation

“Turkey sentences journalists to life in jail over coup attempt,” The Guardian

“Myanmar policeman who detained Reuters pair ‘did not know arrest procedures’,” Reuters

“Slain Slovak journalist was targeted by Italian mafia, says colleague,” Deutsche Welle

“CPJ urges Kyrgyzstan to drop case against journalist,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

“Release Kashmiri photojournalist Kamran Yusuf immediately, demands CPJ,” Scroll