On the first Saturday of November 2014, when media owner and broadcaster David Tam Baryoh switched on the mic for his weekly “Monologue” show on independent Citizen FM in Freetown, Sierra Leone, he had no idea that criticizing the government’s handling of Ebola would mean 11 days in jail.

The three West African countries in which the epidemic is concentrated–Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone–are among the poorest in the region. According to a report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa released in December 2014 on the socioeconomic impact of Ebola, the economies of the three together account for only 2.42 percent of West Africa’s GDP and 0.68 percent of the African continent’s as a whole.

The report concluded that, “at least in economic terms, there is no need to worry about Africa’s growth and development prospects because of EVD [Ebola virus disease].” It also makes this recommendation: “Africa media and communication houses–print and audio-visual–should be encouraged to provide accurate and fact-based accounts on EVD. They should cover progress made to reverse its spread and impact.”

The idea was laudable: that the media (in Africa and elsewhere) should report accurately and avoid playing into stereotypes that the continent is a place of disease and despair. But focusing only on the good news of “progress” against Ebola would be a disservice to the citizens of the three countries, say journalists in the affected countries who spoke with CPJ.

Although the U.N. report may be correct in stating that the continent’s rising growth and development prospects will not be endangered by the impact of Ebola, the potential exists for profound long-term effects in the three West African nations. Already impoverished by conflict and with inadequate health care systems, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone must cope with the trauma and tragedy of individual deaths, as well as the loss of a great many who have died of the disease from their small pools of skilled medical and other professionals. Without a robust, independent press to ask questions and hold governments to account about how money is spent and how society should be rebuilt and sustained, the prospects for genuine socioeconomic development that benefits all seem dim, says Sierra Leone radio journalist Mustapha Dumbuya.

Yet, as David Tam Baryoh’s experience illustrates, even asking such questions on the public airwaves can carry a price in the current environment.

Baryoh’s “Monologue” program is more than its name suggests in that it includes interviews and call-ins from listeners. On the show in question, Baryoh’s criticism of Sierra Leone President Ernest Bai Koroma likely precipitated his arrest, local journalists told CPJ. Baryoh had questioned Koroma’s intention to run for a third term and interviewed an opposition party spokesman who criticized the Koroma government’s handling of the Ebola outbreak, according to local news reports.

The Monday after the show aired, November 3, 2014, police officers arrested Baryoh at his office without a warrant. Kelvin Lewis, president of Sierra Leone’s Association of Journalists, told CPJ that they later showed him an executive detention order, signed by Koroma, that accused him of incitement. The day after his release, on November 14, Baryoh was behind the mic again, but he has since stayed off the air as a safeguard against further offending the authorities, he told CPJ.

Baryoh said that no charges have been filed against him and that each Monday he must report to the police, who have confiscated his passport and said that they will not release it until they hear “from above” when they may do so. “If you don’t have your passport, you are not free,” Baryoh said.

The lesson for other Sierra Leonean journalists is clear: Self-censor or run the risk of arrest, said Dumbuya. “Journalists have lots of questions about how Parliament is spending the millions of dollars donated for Ebola, but at the moment they are scared to ask,” Dumbuya said. “They are worried they might be arrested. Under this state of emergency, the government doesn’t need to explain if it makes an arrest. Accountability has been shelved. MPs [members of Parliament] just say, ‘Ask your questions after Ebola.'”

The government of Sierra Leone imposed the state of emergency in July 2014, ostensibly to help contain Ebola. The order provides sweeping powers to the military to restrict the movement of people, enforce curfews, and conduct house-to-house searches for those who might be infected with the virus. In December 2014, Sierra Leone’s Parliament extended the emergency regulations for another 90 days. In a speech on December 17, President Koroma maintained the prohibition on all public gatherings, suspended trading on Sundays, and limited “traders and market women” to trading between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays and half-days on Saturdays “until further notice.”

Schools also remain closed in Sierra Leone, prompting one journalist (who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal) to remark that the suspension of classes made little sense when people were still mingling freely at markets. “They could rather open the universities and schools to educate people on how to fight the sickness, yet young girls are allowed to wander through the market,” he told CPJ. “It doesn’t make sense.”

In fact, the routine quarantining of citizens and lockdown of communities have failed to combat the epidemic, according to Sharon Ekambaram, the head of Médecins Sans Frontières South Africa’s Dr. Neil Aggett Unit, who spent a month as an advocacy liaison officer in Freetown. While there, Ekambaram observed that quarantine confined the healthy and the sick together and concluded that the top-down, authoritarian approach allowed no space for people to express opinions publicly about how the crisis is being handled.

“Patients have no voice and there are no media willing to speak about human rights,” the South African Ekambaram–who is also a veteran AIDS activist–told CPJ. “During the struggle for [AIDS] treatment in South Africa, the media took a stand and learned with us, but there are no civil society organizations in Sierra Leone.” Ekambaram said that fear and the stigma of Ebola are still the key issues driving the disease underground. The absence of strong patient advocates in Sierra Leone means that there is little opportunity to personalize the issue, get beyond the statistics, and focus media attention on an appropriate response.

Baryoh, for his part, is reluctant to speculate on the record about what he said during his broadcast that drew such a swift reprisal from the president, and his absence from the airwaves means one less voice in Sierra Leone to raise critical questions and the concerns of citizens.

In a country with a high illiteracy rate, where newspapers are expensive items available mostly to those earning a salary and living in the city, radio is a vital source of information, and listeners tune in enthusiastically, said another journalist from Sierra Leone who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal.

“People love independent media because we raise questions that affect them, such as ‘Why go to hospital when you don’t get service, and why is every sickness now being classified as Ebola?'” the journalist said. “People send text messages, even email if they can afford it, but then, when you raise these issues in the media, government gets angry.”

“Ebola brings to the forefront not just the issue of accountability but also of trust,” Anne Bennett, the executive director of Hirondelle USA, told CPJ. The non-profit organization supports and trains community radio stations across West and Central Africa, and, Bennett said, many of the stations with which they work in Guinea and Sierra Leone were alert to the presence of Ebola long before the government acknowledged and announced an epidemic.

“People don’t trust government, but they do trust local reporters who come from their own communities,” Bennett said. Small media operations need support, whether in the form of funding, management training, or a reformed legal framework that enables them to operate freely, she said.

In many ways, Bennett said, Ebola has highlighted problems not only with health services and other public institutions but also with the media. “It’s not just about training and financing but about the media framework … We need strong and credible media,” she said. “Media has a vital role to play in informing communities to become resilient.”

In a report titled Ebola and Freedom of Expression in West Africa, the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) urged governments in the region to “provide education and access to information concerning health problems by recognizing and respecting the role of freedom of expression, particularly media freedom, can play in raising awareness about Ebola.” In an interview about the report with the International Press Institute, the MFWA’s program officer for free expression rights monitoring and campaigns, Anjali Manivannan, observed, “Trust is key in spreading timely, accurate information about any subject.”

Manivannan noted that the countries most affected by Ebola are also recovering from armed conflicts or authoritarianism and that, as a result, “trust in government authorities is weak.” She added that community radio stations play a key role by providing a means for trusted religious, traditional, or community leaders to relay information to people in towns and villages across the region. When respected fellow citizens talk about Ebola–its symptoms, prevention, and containment methods–they may be more effective than state officials, she said.

Without trustworthy information there is also the potential for ill-informed community members to unintentionally spread inaccurate information. In Guinea, fear and misinformation about Ebola ended in tragedy for a journalist with the privately owned Liberté FM and two radio technicians from Radio Rurale de N’Zérékoré, who were murdered by villagers, along with five health care workers, in the southeastern Guinean village of Womey. The mob was reportedly afraid that the workers, part of an Ebola public awareness campaign, were spreading the disease. Guinean authorities promised to investigate and bring the perpetrators to justice, according to news reports, but in late 2014, Alpha Diallo, a director at Liberté FM, told CPJ that no one had been charged despite more than 40 arrests.

Independent media have also come under threat during the Ebola epidemic in neighboring Liberia, where the government imposed a state of emergency in early August and journalists were subject to a general curfew and threatened with arrest for talking to patients in the Ebola treatment units. Liberian police assaulted a journalist from the independent FrontPage Africa who was covering a demonstration against the imposition of a 90-day state of emergency, and other independent publications have seen their staff harassed or have been closed down. Journalists were later exempted from the curfew, but access to patients in the treatment units was strictly controlled. “We were warned by government that the patients needed privacy,” said FrontPage Africa journalist Mae Azango, who reported on issues such as a lack of food in certain units but says that she was also unable to report from the high-risk areas because “there were no PPE [personal protective equipment] suits.”

In a September 2014 letter to Justice Minister Christiana Tah, the Press Union of Liberia listed numerous incidents of harassment of the media, including threats against the privately owned Women Voices for a story alleging police corruption in the distribution of Ebola crisis funds, according to news reports; against FrontPage Africa–a critical paper whose editor has been harassed on previous occasions, according to CPJ research; as well as the National Chronicle, which has been closed since an August 2014 police raid.

Police forced the closure of the privately owned Chronicle after the publication of three stories in a planned 10-part series about a group of Liberians who want President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to step down over allegations of corruption and misrule and to form a new government, National Chronicle publisher Philipbert Browne told CPJ in September 2014.

Browne told National Public Radio’s “On the Media” program in December 2014 that the subsequent police report had resulted in no charges being brought against him but that his paper remained closed as an “administrative action,” which he is fighting in Liberia’s Supreme Court. “If the Chronicle is opened today, it will start reporting just where it left off … they should not think they can subdue me,” he said on the program.

Azango, a 2012 recipient of CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award, said, “Instead of fighting Ebola, they have been fighting journalists … The president asked for absolute power to jail anyone who spoke against the government.” Azango contends that the two state-owned media channels report only what the government says but that privately owned newspapers and TV and radio stations report on the realities of life in Liberia and help create awareness about Ebola. “The people phone the radio station or read the newspaper before they believe anything–most of the burden [of explaining Ebola] has been resting on our shoulders,” she said. “We report what we see.”

Azango is concerned about how Ebola treatment is consuming Liberia’s health care resources, leaving patients with malaria and diabetes untreated and pregnant women at risk of death because Ebola health facilities will not accept them. “Our health system was crippled before, but Ebola came and killed it,” said Azango emphatically.

Liberia lifted its state of emergency in mid-November, but the midnight-6 a.m. curfew remains and the crisis is far from over. “Children are not in school; no one knows when schools will reopen. We have to rebuild the entire health system, the education system, the civil service–everything has been hit by Ebola,” Azango said. “Two hundred and fifty medical doctors have died. We have no doctors again.” In addition to publicizing how the epidemic is being fought, in Azango’s view, the media have a responsibility to highlight the stories of survivors and the challenges they face. “They are coming home to nothing–their homes and all their possessions were burned as part of the fight against the virus, but they are getting nothing,” she said.

In the face of immense grief and need and the potential for discontent in the three nations, the media offer a mechanism for communication between citizens and their governments and for ensuring that elected officials do not assume authoritarian roles as a result of the crisis, Anne Bennett said.

Bennett is concerned that the international community has been tacitly complicit in the control of local media by governments in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea under the pretext that it’s necessary to deal with the current crisis. “We would never tolerate that in our own countries, so how committed are we really to free and independent media [in West Africa]?” she asked.

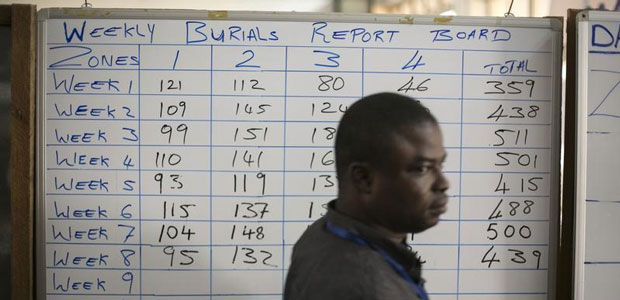

The importance of a vigilant and independent media was highlighted on December 8, 2014, after the National Ebola Response Centre’s revelation that some 6,000 “ghost” names had been discovered in its weekly payroll order. Lewis, with the Sierra Leone Association of Journalists, responded to the disclosure with a statement that read, in part, “As journalists, we are going back to our watchdog role of unearthing corruption where it is practiced. This does not mean we are going to abandon our role of educating and sensitizing Sierra Leoneans about the Ebola disease, but we believe this action will ensure monies meant to fight the spread of the virus are used judiciously and for the intended purpose.”

Sue Valentine is CPJ’s Africa program coordinator. She has worked as a journalist in print and radio in South Africa since the late 1980s for private media, public broadcasting, and the nonprofit sector, covering a range of topics, including South Africa’s transition to democracy and the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The 18th paragraph has been corrected to reflect that Anne Bennett is executive director of the non-profit organization Hirondelle USA.