Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif made a series of commitments to safeguard press freedom during a meeting with a CPJ delegation last week. Among them was a pledge to speak out in support of media freedom and against attacks on journalists, particularly in high-conflict areas like Baluchistan.

Baluchistan–Pakistan’s largest province by area–has been mired in a separatist conflict since the inception of Pakistan in 1947. Some journalists have termed Baluchistan Pakistan’s black hole. Local journalists work in a climate of intense intimidation and risk being killed by an array of actors, including Pakistani security forces and intelligence agencies, state-sponsored anti-separatist militant groups, pro-Taliban groups, and Baluch separatists. Foreign journalists seeking to cover the restive province face tight restrictions.

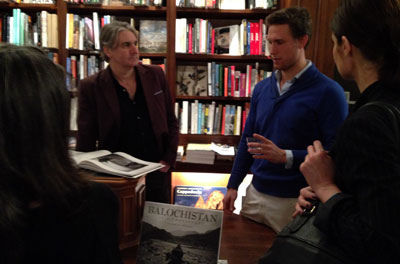

Last month, Pakistani authorities denied British journalist Willem Marx an entry visa to participate in a panel on reporting in Pakistan at the Lahore Literary Festival. The apparent reason: his newly released book, Balochistan at a Crossroads. Pakistani consular staff in New York informed Marx he was not welcome in the country. Marx told CPJ that after much probing, the consular official muttered to him, “It was the agencies”–a term used for Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus, which includes the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

This wasn’t the first time Marx had dismayed Pakistan’s intelligence agencies. During his reporting in 2009–despite obtaining a No Objection Certificate (NOC), without which foreigners are generally not allowed into the province–it was clear Marx was not welcome there by the ISI. “It’s an incredibly intimidating place to work,” he said. ISI agents followed him throughout his time there, he told me. As a result, it was at times difficult for Marx to get people to meet with him, because to do so would invite trouble from the intelligence agencies. There are checkpoints everywhere in the province, he said.

On his departure from the country, authorities detained Marx for over an hour at the Karachi airport. The unidentified officials who held him said the intelligence agencies were not happy about his meeting with a Baluch separatist group during his reporting trip to the province. The officials confiscated one of Marx’s videotapes.

Marx returned to Pakistan four years later to cover the assassinations of polio workers. “It was without any problem. It was officially approved, and I was even given a security escort,” Marx said.

Apparently, reporting on Baluchistan is a red line that foreign journalists must not cross. “I seem to be blacklisted for writing a book on Baluchistan,” he told me.

But, as is often the case with censorship attempts, blacklisting Marx has only backfired. Marx told me that had he simply been allowed to enter the country and speak on the panel at the literary festival, the findings of his book would have been shared with a few of Lahore’s elite. But barring him entry has drawn widespread domestic and international attention to his book and the situation in Baluchistan. Shortly after Marx was denied a visa, prominent Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir with a following of almost half a million people tweeted:

@WillemMarx Sorry to hear that you were denied a visa just because you wrote something on the situation of Balochistan

— Hamid Mir (@HamidMirGEO) February 21, 2014

This is but a glimpse into the array of challenges journalists face in the restive province. “It’s a complete nightmare,” Marx said about the state of press freedom there. “Foreign journalists will simply get deported for reporting on Baluchistan. It’s much more of a mortal risk to local journalists.” CPJ research shows at least six journalists have been murdered in Baluchistan in direct relation to their work, and another seven have been killed in the province where the motive remains unclear.

In the past few weeks alone, CPJ’s Asia Desk has come across two cases of Baluch journalists who have been killed. Last month, men riding on motorcycles fired shots on and killed Ijaz Mengal, a stringer for the daily Intekhab and a clerk in the provincial education ministry, according to the Pakistan-based Freedom Network. The Baloch National Army, a separatist group, claimed responsibility for the killing and accused him of spying for the government’s security agencies. Mengal’s relatives denied the accusation. His brother, Riaz Mengal, also a journalist, has gone underground after continued threats, reports said.

A few days earlier, gunmen killed Muhammad Afzal Khwaja, a journalist with Zamana, a Quetta-based Urdu language newspaper, as well as its sister publication Balochistan Times, according to news reports. No one has claimed responsibility for the murder and the motive remains unclear.

With limited information and the fact that journalists in the province often straddle political activism and journalism, establishing a motive in these cases is almost always a challenge. But as Marx noted: “While some Baluch journalists are politically active, journalism here, by definition of the Pakistani state, is activism. Journalists who are reporting on the realities are automatically viewed as activists by the Pakistani state, which would rather keep things here under wraps and deprive them oxygen.”

This is where Sharif’s commitments can come into play. The prime minister can begin to chisel away at the deep-rooted culture of impunity by ensuring effective investigations into the killings of local journalists in Baluchistan and holding the perpetrators to account. In addition, he can send a clear signal that attacking foreign journalists like Carlotta Gall of The New York Times will not be tolerated in the future. He can also ensure that foreign journalists like Marx, and The New York Times’ Declan Walsh, who was expelled last year, are not punished for their reporting.