Impunity and lack of solidarity expose India’s journalists to attack

By Sumit Galhotra

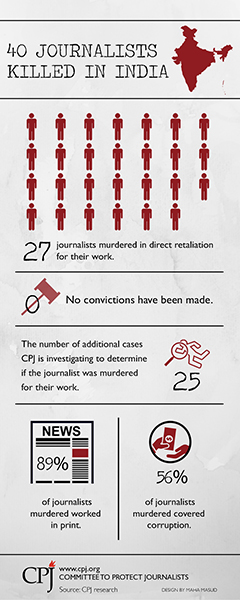

Corruption scandals make for attention-grabbing headlines, but when journalists who expose wrongdoing are killed, their murder is often the end of the story. For eight years India has been a fixture on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual Impunity Index, which spotlights countries where journalists are slain and their killers go free. Perpetrators are seldom arrested and CPJ has not recorded a single conviction upheld in any of the cases of journalists murdered in India in direct relation to their work.

Of the 27 journalist murders documented in the country by CPJ since 1992, corruption and politics were the two deadliest beats. With its poor impunity record and an escalation in journalists being harassed or attacked, particularly in states such as Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, CPJ took an investigative trip to India in March 2016 to speak with members of the press, lawyers, and the relatives of three dead journalists, to try to understand the challenges in attaining justice and the risks faced by reporters on the front lines of exposing wrongdoing.

The challenges faced by India’s press are highlighted by the cases of Jagendra Singh, Umesh Rajput, and Akshay Singh, whose deaths are examined in this report. Corruption was the impetus for all three journalists’ final reports and in all three cases, there have been no convictions. Freelancer Jagendra Singh, who died from his injuries after allegedly being set on fire by the police in June 2015, was reporting on allegations that a local minister was involved in land grabs and a rape. Before he was shot dead in January 2011, Umesh Rajput was reporting on allegations of medical negligence and claims that the son of a politician was involved in an illegal gambling business. Investigative reporter Akshay Singh was working on a story linked to the US$1 billion Vyapam admissions racket when he died unexpectedly in July 2015.

As well as a marked difference in the risks faced by small-town journalists compared with those from larger cities and outlets, CPJ found a pattern of resistance by authorities to carry out independent investigations and a legal process hindered by extensive delays. Lawyers and families of journalists with whom CPJ spoke said that often police failed to carry out adequate investigations or to identify and apprehend attackers. In an exception to how journalist killings are usually dealt with in India, two of the three cases examined in the report are being handled by India’s national-level agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation. Media organizations have called for all journalist killings to be handled by the bureau.

‘Corruption has become a dangerous disease’

Journalists and whistleblowers, including activists who use the Right to Information law, have played an indispensable role in exposing corruption in India. In the past few years, the country has been hit by a series of scandals, including allegations of the misuse of funds when India hosted the 2010 Commonwealth Games, and the 2011 telecommunications bribery case known as the 2G Scam, which made Time magazine’s “Top 10 Abuses of Power” list, second only to Watergate in the U.S. Corruption by police and other government institutions makes daily headlines.

Attempts to address the issue were made in 2011 when an activist named Anna Hazare staged a hunger strike to demand instituting an independent ombudsman to prosecute politicians and civil servants suspected of corruption. His anti-corruption movement paved the way for the formation of the Aam Aadmi Party, which is focused on ending corruption. The party currently holds the main seat of power in Delhi.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi also made combatting corruption a central issue in his election campaign when his Bharatiya Janata Party swept to power in 2014. “Corruption has become such a dangerous disease in the country. It is worse than even cancer and can destroy the country,” Modi said at a rally in August of that year, after the previous Congress-led government was implicated in a series of high-profile scandals.

Despite vowing to take action on corruption, authorities have done little to protect the journalists who are on the front lines in trying to expose wrongdoing, media experts said. No government in India has been an ardent champion of press freedom. The silence by all who have been at the helm of power over the years—be it the Congress Party, Bharatiya Janata Party, or the regional parties that head state or municipal governments—has only fostered a culture of impunity.

Obstacles to securing justice

The sheer size of India—with a population of 1.2 billion spread over 29 states and seven union territories—coupled with a decentralized system of government adds to the challenge of securing justice. The states exercise jurisdiction over law and order, complicating efforts to ensure a nationwide response to anti-press violence.

Families seeking justice face a long and complicated process that starts with a First Information Report, which is the initial step in getting police to register a complaint and take action. As CPJ research shows, the process rarely reaches the prosecution stage.

Geeta Seshu, the Mumbai-based consulting editor of media watch website The Hoot, said that she did not believe law enforcement was fulfilling its role in bringing perpetrators to justice.

She said she could think of several cases where the police’s first line of response to a threat, attack, or killing of a journalist was to claim that the victim was not a journalist or that the attack was not work-related. “There is a deflection and that becomes the narrative then. That becomes the course of the investigation also.”

“Our criminal justice system depends a lot on the local police,” she said. Police are responsible for the first stages in any investigation. A faulty First Information Report, not applying the appropriate sections of the law, not clearly recording witness statements or protecting vulnerable witnesses, and not following up on preliminary investigations can be damaging, she said.

On rare occasions, a case is allowed by state authorities or the Supreme Court to be handled by the Central Bureau of Investigation, but that does not always result in a more efficient process. In September 2015, the bureau admitted to the Supreme Court that it was overworked and under-staffed. Close to 16 percent of posts, around 724, were vacant; and the bureau was investigating more than 1,200 cases and had 9,000 pending in court, according to reports citing sources from the investigative body. Journalists and a lawyer told CPJ that a benefit of the Central Bureau of Investigation is that it tends to be removed from local power structures that could influence an investigation, but they were unsure of the agency’s effectiveness.

CPJ is aware of only one murder in the past 10 years in which a suspect was convicted. However, the suspect was released on appeal. Even if a court hears the case, there will be delays. Government data show that more than 31 million cases were pending in India’s court system at the end of 2013, according to the latest figures available to CPJ.

“The torturously slow Indian judicial system, together with corruption in the police force and the criminalization of politics, makes it possible to literally get away with murder,” Sujata Madhok, general-secretary of the Delhi Union of Journalists, told CPJ.

In a 2015 report on the safety of journalists, the Press Council of India, a body set up by Parliament in 1966 to act as watchdog for press freedom and journalism ethics, found that “even though [the] country has robust democratic institutions and vibrant and independent judiciary, the killers of journalists are getting away with impunity. The situation is truly alarming and would impact on the functioning of the democratic institutions in the country.” The council, which is chaired by a retired judge and made up of 28 members including working journalists, members of parliament, and experts in law, academia, and culture, has advocated that parliament enact a nationwide journalist safety law. It also wants to see the Central Bureau of Investigation, or another national-level agency, investigate cases of journalists murdered and to complete its investigation within three months.

State ministers, police divisions, and the Central Bureau of Investigation did not respond to CPJ’s requests for interviews or comment on the status of the cases examined in this report.

Divide between rural and city journalists

CPJ found that those reporting in remote and rural areas in India are at greater risk of threats and violence. Often those working in such areas are responsible for finding advertisements, handling distribution as well as reporting, local journalists and media experts told CPJ. Furthermore, pay is low and financial security is lacking.

“They rarely get support from their employers if they are targeted. They are seldom members of unions as they live in places where there are hardly any other journalists,” Sujata Madhok said.

CPJ research into attacks and harassment in India shows that cases of violence against journalists from larger towns and cities, and those who work for major news outlets, tend to attract greater attention than their small-town counterparts. “The gulf between journalists working in rural or remote areas and those working in big cities is huge,” said Geeta Seshu, from The Hoot.

Delhi-based Akshay Singh belonged to the India Today Group, one of the largest media houses in the country. High-ranking officials from across the political spectrum attended his funeral. His outlet joined the family’s calls for the Central Bureau of Investigation to handle his case. But for Jagendra Singh, a freelancer from a rural town in the state of Uttar Pradesh, police were quick to discredit his press credentials after his death. CPJ was told by an investigating officer at the time, “He only wrote on social media.”

Geeta Seshu told CPJ that journalists reporting for major outlets are more likely to be viewed as credible, while the legitimacy of small-town journalists often comes into question.

Sevanti Ninan, a Delhi-based columnist and founding editor of The Hoot, added, “In India there is this fussing about who is a journalist. But we can agree these are newsgatherers. There is newsgathering, and that is a function that gets them into trouble.”

Online trolls, commentators, and politicians are also quick to vilify the press, according to media experts. CPJ found terms like “presstitutes” and “sickular media” across social media. Right-wing Facebook groups such as Presstitutes and India Against Presstitutes, both of which have tens of thousands of followers, are openly critical of journalists and opposition politicians. According to Sujata Madhok, women journalists are the most vulnerable to abuse, threats of violence, and slander campaigns online. Complaints to police have been fruitless, she told CPJ.

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, a senior journalist and former member of the Press Council of India, said, “It has become fashionable to denigrate the media with ministers in this government, and to tarnish everyone with the same brush.” He said that instances of corruption and ethical lapses by segments of the Indian media resulted in a loss in credibility for the Indian press as a whole.

A fragmented press

Several journalists with whom CPJ spoke echoed the view that there is little outrage among the media fraternity and society at large when a journalist is attacked or killed in India. One exception was in February 2016 when prominent journalists in New Delhi marched in unity to protest an attack in which a crowd of lawyers beat and threatened members of the press who had gathered to cover a high-profile hearing at the city’s Patiala House court complex. In contrast, the same week CPJ documented how Karun Misra, a journalist from a small town a 12-hour drive from the capital, was shot dead in apparent retaliation for his work. His killing neither attracted the same level of attention nor high-profile calls for action.

Geeta Seshu told CPJ that a polarized media has resulted in the lack of a cohesive response to attacks. “Journalists tend to devalue the attacks on themselves as a community and fail to speak out in one voice. We are fragmented ourselves,” she said. “We are very far away from any sort of movement to fight this culture of impunity. Even the culture of protesting these sort of things is often lost to us as journalists.”

She said that media organizations should take greater responsibility for their staff. Some editors at news outlets leave responsibility for journalists’ safety to the government. CPJ has found that while it is important for governments to ensure journalists can safely carry out their work, media organizations play an essential role too, especially in protecting freelancers and local journalists and stringers.

The gulf between journalists working in rural or remote areas and those working in big cities is huge.” Geeta Seshu, The Hoot

Many major Indian cities have press unions, but in the past decade the focus of those unions has been on implementing labor rights for working journalists and media workers, and fighting cases in court to ensure higher wages. However, safety and security issues are quickly becoming a priority, said Sujata Madhok. She said the Delhi Union of Journalists and others are demanding a law that provides safety and security to journalists. In recent months, the unions have organized workshops on conflict reporting and riot coverage, and demanded that employers pay for risk insurance. “These efforts will have to be stepped up given the increasing attacks on journalists,” she said.

In the past year there has been an international drive for the media to unite in protecting colleagues. In February 2015, a coalition of media organizations and press freedom groups signed on to the ACOS (A Culture of Safety) Alliance. The alliance includes guidelines and commitments for freelancers and organizations. More than 65 organizations from several countries have joined the alliance, but so far India is not represented.

Role model for the world

As the world’s largest democracy, it is important that India acts as a role model in safeguarding its media and promoting press freedom on the international stage. As a founding member of the Community of Democracies, an intergovernmental organization that aims to further democratic norms, India has committed to upholding freedom of expression, press freedom, and transparency as core principles. Freedom of expression is also guaranteed under Article 19 of its own constitution. However, India—alongside its neighbors Afghanistan and Bangladesh, and conflict-affected states South Sudan, Somalia, and Syria—failed to provide updates on investigations into journalist killings for the 2014 biannual impunity report of the Director General of UNESCO, the U.N. agency mandated to promote freedom of expression. This failure demonstrates a lack of international accountability, CPJ’s 2015 impunity report found.

If it upheld its commitment to the democratic principles and established a national-level journalist safety and protection mechanism, India would begin making progress in combatting impunity. Authorities there could learn from best practices used by nations facing threats to their media, including Colombia, where a national protection mechanism provides security for journalists under threat, including supplying bulletproof vests, police bodyguards, and offering relocation; and Mexico, where a federal prosecutor’s office was set up to investigate attacks on freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

By providing adequate resources and political support to ensure swift and thorough investigations, India’s government would send a powerful message of support to the nation’s press. The country’s journalists, media organizations, and press unions also have a role to play in speaking out in a strong, unified voice against attacks on their colleagues.