Decisions you make in the field have direct bearing on your safety and that of others. The risks inherent in covering war, political unrest, and crime can never be eliminated, although careful planning and risk assessment can mitigate the dangers.

Be realistic about your physical and emotional limitations. It might be useful to consider in advance all the individuals who would be affected if you were, say, disabled or killed. Consider as well the emotional toll of continuing to report stressful stories one after another. At some point, one more crime victim, one more corpse, one more grieving family may be too much. A decision not to report a story should be seen as a sign of maturity, not as a source of shame or stigma.

News managers should regard the safety of field journalists as the primary consideration in making an assignment. They should not penalize a journalist for turning down an assignment based on the potential risk. News organizations should recognize their responsibilities to support all field journalists, whether they are staff members or stringers. Editors need to be frank about the specific support their organization is willing to provide, including health or life insurance or emotional counseling. Matters left unresolved before a journalist begins a story can lead to stressful complications later.

Security Assessment

Always prepare a security assessment in advance of a potentially dangerous assignment. The plan should identify contact people and the time and means of communication; describe all known hazards, including the history of problems in the reporting area; and outline contingency plans that address the perceived risks. Diverse sources should be consulted, including journalists with experience in the location or topic, diplomatic advisories, reports on press freedom and human rights, and academic research. Editors working with staffers or freelancers should have substantial input into the assessment, take the initiative in raising security questions, and receive a copy of the assessment. An independent journalist working without a relationship with a news organization must be especially rigorous in compiling a security assessment, consulting with peers, researching the risks, and arranging a contact network. An example of a security assessment form is available for download here and for review in Appendix G.

Always prepare a security assessment in advance of a potentially dangerous assignment. The plan should identify contact people and the time and means of communication; describe all known hazards, including the history of problems in the reporting area; and outline contingency plans that address the perceived risks. Diverse sources should be consulted, including journalists with experience in the location or topic, diplomatic advisories, reports on press freedom and human rights, and academic research. Editors working with staffers or freelancers should have substantial input into the assessment, take the initiative in raising security questions, and receive a copy of the assessment. An independent journalist working without a relationship with a news organization must be especially rigorous in compiling a security assessment, consulting with peers, researching the risks, and arranging a contact network. An example of a security assessment form is available for download here and for review in Appendix G.

Risks should be reassessed on a frequent basis as conditions change. “Always, constantly, constantly, every minute, weigh the benefits against the risks. And as soon as you come to the point where you feel uncomfortable with that equation, get out, go, leave. It’s not worth it,” Terry Anderson, the former Associated Press Middle East correspondent who was held hostage in Beirut for nearly seven years, wrote in CPJ’s first journalist security guide, published in March 1993. “There is no story worth getting killed for.”

Risks to be identified may include:

- If operating in a conflict zone, battlefield hazards, such as small arms fire, aerial bombardment, artillery, landmines, booby traps and unexploded ordnance;

- In many parts of the world, terrorist attacks such as suicide bombs, gunmen, knife attack, vehicular attacks and sieges- journalists for ransom or for political objectives;

- Crowd disorder issues, including tear gas, missiles, rubber bullets, kettling, assault from the crowd and sexual assault;

- Criminal risk, from petty crime to violent assault;

- Digital security, including safety of data and protection of sources;

- Government or non-state actor intimidation to silence;

- Long term threats to oneself, sources, contributors as well as your local staff (fixers/drivers);

- Environmental and health issues from natural disasters to vaccination requirements.

(These contingencies and more are addressed in detail in subsequent chapters of this guide.)

The risk assessment must also consider the possibility that any circumstance—from a tense political situation to a natural disaster—can escalate in severity. The assessment should include information on where to stay and where to seek refuge if necessary; where and how to get updated information inside the country; whether equipment such as a weather-band or shortwave radio is needed; whom to contact in the country, from local human rights groups to foreign embassies, for emergency information; travel plans and methods within the country; and multiple entry and exit routes.

It is particularly important to consider the state of local hospitals and know the best ones to use in case of an emergency. This information must be included in the risk assessment. It is also useful to identify your insurance provider’s medical evacuation procedures. Always take a medical kit and detail the medical training of those deploying.

In the assessment, outline a check-in procedure with editors, colleagues, and loved ones outside the area of risk. You and the contact people should decide in advance how frequently you wish to communicate, by what means, and at what prescribed time, and whether you need to take precautions to avoid having your communications intercepted. Most important, you and the contact person must decide in advance at exactly what point a failure to check in is considered an emergency and whom to call for a comprehensive response in locating you and securing your exit or release. The response often entails systematically reaching out to colleagues and friends who can assess the situation, to authorities who can investigate, and to the diplomatic community to provide potential support and leverage.

The assessment should address the communications infrastructure in the reporting area, identifying any contingency equipment you may need. Are electricity, Internet access, and mobile and landline phone service available? Are they likely to remain so? Is a generator or a car battery with a DC adaptor needed to power one’s computer? Should a satellite phone be used? In remote locations or high risk situations, satellite and GSM tracking devices should also be considered. They offer a way to raise the alarm quickly. Ensure that those monitoring your communications are up to the task and dedicated.

Any risk assessment should consider your desired profile. Do you want to travel in a vehicle marked “Press” or “TV,” or would it be better to blend in with other civilians? Should you avoid working alone and instead team up with others? If you travel with others, choose your companions carefully. You may not wish to travel, for example, with someone who has a very different tolerance for risk.

Sources and Information

Protecting sources is a cornerstone of journalism. This is especially important when covering topics such as violent crime, national security, and armed conflict, in which sources could be put at legal or physical risk. Freelance journalists, in particular, need to know that this burden rests primarily with them. No journalist should offer a promise of confidentiality until weighing the possible consequences; if a journalist or media organization does promise confidentiality, the commitment carries an important ethical obligation.

In your communications, protect your sources. Consider whether to call them on a landline or cell, to use open or secure email, and to visit them at home or the office.

Most news organizations have established rules for the use of confidential sources. In a number of instances, news organizations require that journalists in the field share the identity of a confidential source with their editors. Journalists in the field must know these rules before making promises to potential confidential sources. In the United States and many other nations, civil and criminal courts have the authority to issue subpoenas demanding that either media outlets or individual journalists reveal the identities of confidential sources. The choice can then be as stark as either disclosure or fines and jail. Media organizations that have received separate subpoenas will make their own decisions on how to respond. Time magazine, facing the prospect of daily fines and the jailing of a reporter, decided in 2005 that it would comply with a court order to turn over a reporter’s emails and notebooks concerning the leak of a CIA agent’s identity, even though it disagreed with the court’s position.

Media companies have the legal right to turn over to courts a journalist’s notebooks if they are, according to contract or protocol, the property of the media organization. If a journalist is a freelance employee, the media organization may have less authority to demand that a journalist identify a source or turn over journalistic material to comply with a court subpoena.

In some nations, local journalists covering organized crime, national security, or armed conflict are especially vulnerable to imprisonment, torture, coercion, or attack related to the use of confidential information. In 2010, CPJ documented numerous instances throughout Africa in which government officials jailed, threatened, or harassed journalists who made use of confidential documents. In Cameroon, for example, authorities jailed four journalists who came into possession of a purported government memo that raised questions of fiscal impropriety. One of those journalists was tortured; a second died in prison. It’s important to understand that your ethical responsibility could be severely tested in conflict zones by coercive actors who may resort to threats or force.

Journalists should study and use source protection methods in their communications and records. Consider when and how to contact sources, whether to call them on a landline or cell phone, whether to visit them in their office or home, and whether to use open or secure email or chat message. Consider using simple code or pseudonyms to hide a source’s identity in written or electronic files. Physically secure written files, and secure electronic files through encryption and other methods described in Chapter 3 Technology Security.

The identity of a source could still be vulnerable to disclosure under coercion. Thus, many journalists in conflict areas avoid writing down or even learning the full or real names of sources they do not plan to quote on the record.

Laws on privacy, libel, and slander vary within and between nations, as do statutes governing the recording of phone calls, meetings, and public events, notes the Citizen Media Law Project at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society. In many nations, local press freedom groups can provide basic details of privacy and defamation laws, along with the practices of authorities in applying those laws. (Many of these organizations are listed in Appendix E Journalism Organizations; a comprehensive list of press freedom groups worldwide is available through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.) Being a journalist does not give one the right to steal, burglarize, or otherwise violate common laws in order to obtain information.

Security and Arms

Most journalists and security experts recommend that you not carry firearms or other gear associated with combatants when covering armed conflict. Doing so can undermine your status as an observer and, by extension, the status of all other journalists working in the conflict area. In conflict zones such as Somalia in the early 1990s, and Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000s, media outlets hired both armed and unarmed security personnel to protect journalists in the field. While the presence of security guards hindered journalists’ observer status, many media organizations found they had little choice but to rely on private personnel to protect staff in uncontrolled situations.

Carrying a firearm on other assignments is also strongly discouraged. In nations where law enforcement is weak, some journalists under threat have chosen to carry a weapon. In making such a choice, you should consider that carrying a firearm can have fatal consequences and undercut your status as an observer.

Sexual Violence

The sexual assault of CBS correspondent and CPJ board member Lara Logan while covering political unrest in Cairo in February 2011 has highlighted this important security issue for journalists. In a 2011 report, CPJ interviewed more than four dozen other journalists who said that they, too, had been victimized on past assignments. Most reported victims were women, although some were men. Journalists have reported assaults that range from groping to rape by multiple attackers.

Being aware of one’s environment and understanding how one may be perceived in that setting are important in deterring sexual aggression. The International News Safety Institute, a consortium of news organizations and journalist groups that includes CPJ, and Judith Matloff, a veteran foreign correspondent and journalism professor, have each published checklists aimed at minimizing the risk of sexual aggression in the field. A number of their suggestions are incorporated here, along with the advice of numerous journalists and security experts consulted by CPJ.

Understand the culture and be aware of your surroundings. Travel with colleagues and support staff. Stay close to the edges of crowds and have an exit route in mind.

Journalists should dress conservatively and in accord with local custom; wearing head scarves in some regions, for example, may be advisable for female journalists. Female journalists should consider wearing a wedding band, or a ring that looks like one, regardless of whether they are married. Journalists should avoid wearing necklaces, ponytails, or anything that can be grabbed. Numerous experts advise female journalists to avoid tight-fitting T-shirts and jeans, makeup, and jewelry in order to avoid unwanted attention. Consider wearing heavy belts and boots that are hard to remove, along with loose-fitting clothing. Carrying equipment discreetly, in nondescript bags, can also avoid unwanted attention. Consider carrying pepper spray or even spray deodorant to deter aggressors.

Journalists should travel and work with colleagues or support staff for a wide range of security reasons. Local fixers, translators, and drivers can provide an important measure of protection for international journalists, particularly while traveling or on assignments involving crowds or chaotic conditions. Support staff can monitor the overall security of a situation and identify potential risks while the journalist is working. It is very important to be diligent in vetting local support staff and to seek recommendations from colleagues. Some journalists have reported instances of sexual aggression by support staff.

Experts suggest that journalists appear familiar and confident in their setting but avoid striking up conversation or making eye contact with strangers. Female journalists should be aware that gestures of familiarity, such as hugging or smiling, even with colleagues, can be misinterpreted and raise the risk of unwanted attention. Don’t mingle in a predominantly male crowd, experts say; stay close to the edges and have an escape path in mind. Choose a hotel with security guards whenever possible, and avoid rooms with accessible windows or balconies. Use all locks on hotel doors, and consider using your own lock and doorknob alarm as well. The International News Safety Institute suggests journalists have a cover story prepared (“I’m waiting for my colleague to arrive,” for example) if they are getting unwanted attention.

In general, try to avoid situations that raise risk, experts say. Those include staying in remote areas without a trusted companion; getting in unofficial taxis or taxis with multiple strangers; using elevators or corridors where you would be alone with strangers; eating out alone, unless you are sure of the setting; and spending long periods alone with male sources or support staff. Keeping in regular contact with your newsroom editors and compiling and disseminating contact information for yourself and support staff is always good practice for a broad range of security reasons. Carry a mobile phone with security numbers, including your professional contacts and local emergency contacts. Be discreet in giving out any personal information.

If a journalist perceives imminent sexual assault, she or he should do or say something to change the dynamic, experts recommend. Screaming or yelling for help if people are within earshot is one option. Shouting out something unexpected such as, “Is that a police car?” could be another. Dropping, breaking, or throwing something that might startle the assailant could be a third. Urinating or soiling oneself could be a further step.

The Humanitarian Practice Network, a forum for workers and policy-makers engaged in humanitarian work, has produced a safety guide that includes some advice pertinent to journalists. The HPN, part of the U.K.-based Overseas Development Institute, suggests that individuals have some knowledge of the local language and use phrases and sentences if threatened with assault as a way to alter the situation.

Protecting and preserving one’s life in the face of sexual assault is the overarching guideline, HPN and other experts say. Some security experts recommend that journalists learn self-defense skills to fight off attackers. There is a countervailing belief among some experts that fighting off an assailant could increase the risk of fatal violence. Factors to consider are the number of assailants, whether weapons are involved, and whether the setting is public or private. Some experts suggest fighting back if an assailant seeks to take an individual from the scene of an initial attack to another location.

Sexual abuse can also occur when a journalist is being detained by a government or being held captive by irregular forces. Developing a relationship with one’s guards or captors may reduce the risk of all forms of assault, but journalists should be aware that abuse can occur and they may have few options. Protecting one’s life is the primary goal.

News organizations can include guidelines on the risk of sexual assault in their security manuals as a way to increase attention and encourage discussion. While documentation specific to sexual assaults against journalists is limited, organizations can identify countries where the overall risk is greater, such as conflict zones where rape is used as a weapon, countries where the rule of law is weak, and settings where sexual aggression is common. Organizations can set clear policies on how to respond to sexual assaults that address the journalist’s needs for medical, legal, and psychological support. Such reports should be treated as a medical urgency and as an overall security threat that affects other journalists. Managers addressing sexual assault cases must be sensitive to the journalist’s wishes in terms of confidentiality, and mindful of the emotional impact of such an experience. The journalist’s immediate needs include empathy, respect, and security.

Journalists who have been assaulted may consider reporting the attack as a means of obtaining proper medical support and to document the security risk for others. Some journalists told CPJ they were reluctant to report sexual abuse because they did not want to be perceived as being vulnerable while on dangerous assignments. Editorial managers should create a climate in which journalists can report assaults without fear of losing future assignments and with confidence they will receive support and assistance.

The Committee to Protect Journalists is committed to documenting instances of sexual assault. Journalists are encouraged to contact CPJ to report such cases; information about a case is made public or kept confidential at the discretion of the journalist.

Captive Situations

All over the world journalists are regarded as potentially lucrative abductees by criminal gangs and violent actors.

In Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State has not only used the ransoming of journalists as a major source of funding, but they have also murdered journalists, both local and international. The videotaped killings of James Foley and Steven Sotloff in 2014, after both men were kidnapped and held captive by the Islamic State, cast a spotlight on the dangers of abduction to journalists.

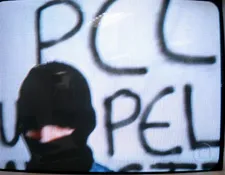

Kidnapping is not a new risk. The kidnapping of journalists for ransom or political gain has occurred frequently since CPJ was founded in 1981. Numerous cases have been reported in nations such as Colombia, the Philippines, Russia, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Mexico, and Somalia, according to CPJ research.

The best antidote is precaution. Research extensively the nature and prominence of the threat. Kidnappings can last years before the criminals have extorted all possible money out of the family and loved ones. Even then there is no guarantee that the victims will be returned. Carefully consider how high the threat is, taking into account whether you would want to expose your family to this kind of trauma.

Travel in teams in dangerous areas, making sure that editors and perhaps a trusted local individual know your plans. Use tracking devices to raise the alarm quickly, and prepare a contingency plan with contact information of people and groups to call in the event you go missing. In advance discussions with editors and trusted contacts, decide the length of time at which they should interpret your being out of touch as an emergency. Consider which individual or group may have leverage over the kidnappers, and try to create a relationship with them before embarking on work in areas where there is a high-risk of kidnapping.

If you’re taken captive, one of the first things a kidnapper may do is research your name on the internet. Everything about you online will be seen by your abductors: where you have worked, the stories you have reported, your education, your personal and professional associations, and possibly the value of your home and your family’s net worth. You may want to limit the personal details or political leanings you reveal in your online profile. Be prepared to answer tough questions about your family, finances, reporting, and political associations.

Be prepared for your bank accounts and financial savings to be extorted as kidnappers often demand passwords. If possible, give a trusted individual power of attorney over your finances so your accounts can be frozen in an emergency. Formally identifying a family member or an individual who can make decisions for you can avoid stagnation during a crisis.

Hostile environment training includes coping mechanisms and survival techniques. Among them is developing a relationship with your captors, a step that could reduce the chance guards will do you harm. Cooperate with guards but do not attempt to appease them. As best as you can, explain your role as a non-combatant observer and that your job includes telling all sides of a story. Pace yourself throughout the ordeal and, as much as possible, maintain emotional equanimity. Promises of release may not be forthcoming; threats of execution could be made.

Journalists captured as a group should act in a way that leads guards to keep them together rather than separate them. This could involve cooperating with guards’ orders and persuading captors that it would be less work to keep the group together. Journalists should offer each other moral and emotional support during captivity. Maintaining cohesion could help each captive’s chances of successful release.

Opportunities for escape may arise during captivity, but many veteran journalists and security experts warn that the chance of success is exceedingly slim and must be balanced against the potentially fatal consequences of failure. In 2009, in Pakistan, New York Times reporter David Rohde and local reporter Tahir Ludin did escape from Taliban captors who had held them for seven months. After weighing the risks, the two men concluded their captors were not seriously negotiating for their release and chose “to try to make a run for it,” Rohde later wrote. Some captors, however, may have a cohesive chain of command in which you may eventually be allowed to make the case that you are a reporter who deserves to be released.

During a captive situation, editors and family members are encouraged to work together. As soon as the captive situation is confirmed, they should get in touch with government representatives in the hostage nation, along with authorities in the news organization’s home country and that of each of the journalists. They should seek out advice from diplomats experienced in the theater, private security experts, and press groups such as CPJ. In 2016, CPJ created the Emergencies Response Team, which is able to advise journalists and their families in times of crisis.

Beyond CPJ, the International News Safety Institute has a Global Hostage Crisis Help Centre that can recommend hostage experts. The Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma can advise affected parties on how to obtain counseling for family members and others. (See Chapter 10 Stress Reactions.) Whether to meet captors’ demands is a difficult question. Patience and emotions will be tested as the ordeal goes on.

Editors and relatives should make every effort to present a cohesive front, designating a person as a conduit to authorities and as a public spokesperson. Authorities may well make decisions independent of (and contrary to) the wishes of family and colleagues, but establishing a clear and consistent message to authorities and the press improves the chance of effectively influencing decision-making.

Most governments have stated policies of not paying ransom demands, although in practice a number of governments, including those of France and Japan, have reportedly helped pay ransom in exchange for the release of captive journalists. Editors and family members may or may not be able to influence decisions on the deployment of a government rescue operation. The American and British governments have a strict policy of non-payment of ransoms to proscribed terrorist groups and, in at least one case, have threatened families with potential prosecution when the question was raised. In Syria, this policy resulted in the death of several journalists, while non-British or American colleagues were freed following a ransom payment.

Kidnappers may try to coerce a news organization into running propaganda or one-sided coverage of their viewpoint. In the 1990s, leftist guerrillas and rightist paramilitaries in Colombia often kidnapped journalists to coerce news outlets into coverage of their political grievances. In 2006, Brazil’s TV Globo aired a homemade video detailing perceived deficiencies in prison conditions after a local criminal gang kidnapped a station reporter and technician. The two journalists were later freed. Editors need to recognize that acceding to kidnappers’ demands could invite future attempts at coerced coverage.

In another form of coercion, captors may demand that a journalist make propagandistic statements on video. Some journalists have agreed, calculating that it may increase their chances of safe release. Others have resisted in the belief that displaying independence may give them some leverage with their captors. The decision depends entirely on the circumstances and the individuals involved. John Cantlie, a British journalist who has been held by the Islamic State since 2014, has been forced to make propaganda videos for the group.

Responding to Threats

Threats are not only a tactic designed to intimidate critical journalists; they are often followed by actual attacks. More than one fourth of journalists murdered in the last two decades were threatened beforehand, according to CPJ research. You must take threats seriously, paying particular heed to those that suggest physical violence.

How to respond depends in part on local circumstances. Reporting a threat to police is usually good practice in places with strong rule of law and trustworthy law enforcement. In nations where law enforcement is corrupt, reporting a threat may be futile or even counterproductive. Those factors should be weighed carefully.

Do report threats to your editors and trusted colleagues. Be sure they know details of the threat, including its nature and how and when it was delivered. Some journalists have publicized threats through their news outlets or their own blogs. And do report threats to local and international press freedom groups such as the Committee to Protect Journalists. CPJ will publicize a threat or keep it confidential at your discretion. Many journalists have told CPJ that publicizing threats helped protect them from harm.

Journalists under threat can also consider a temporary or permanent change in beat. Editors should consult closely with a journalist facing threats and expedite a change in assignment if requested for safety reasons. Some threatened journalists have found that time away from a sensitive beat allowed a hostile situation to lessen in intensity.

In severe circumstances, journalists may consider relocation either within or outside their country. Threatened journalists should consult with their loved ones to assess potential relocation, and seek help from their news organization and professional groups if relocation is deemed necessary. The Colombian investigative editor Daniel Coronell and his family, for example, relocated to the United States for two years beginning in 2005 after he faced a series of threats, including the delivery of a funeral wreath to his home. Coronell resumed his investigative work when he returned to Colombia, and although threats continued, they came at a slower pace and with lesser intensity. CPJ can provide advice to journalists under threat and, in some cases, direct support such as relocation assistance.