Bruno Jacquet Ossébi, a Franco-Congolese journalist known for outspoken coverage of government corruption in the Republic of Congo, dies after a mysterious fire burns down his house. By Mohamed Keita with reporting by Sarah Turbeaux

For most of a late January evening, Bruno Jacquet Ossébi had been propped in front of a flickering television in his home in Brazzaville, capital of the Republic of Congo, watching images of the historic inauguration of Barack Obama half a world away. Fire suddenly erupted. Flames sped through the one-story, two-bedroom house shortly after 1 a.m. on January 21, killing Ossébi’s companion and her two boys, ages 8 and 10. The 44-year-old Ossébi, badly burned, died 12 days later, just before a scheduled medical transfer to his native France.

The official Brazzaville fire service report identified the cause of the blaze as a “short circuit,” although Lt. Col. Alphonse Yamboula, commander of the Brazzaville fire rescue center, acknowledged in a CPJ interview that the finding was not based on any forensic investigation.

Numerous questions have arisen. Ossébi was known for his outspoken coverage of alleged government corruption and his support for a lawsuit that seeks to uncover the purportedly extravagant personal holdings of African leaders. Ossébi’s brother, Roland Kouka, told CPJ that family members fear the fire may have been set to retaliate for the journalist’s coverage of alleged official corruption.

In February, police and judicial authorities acknowledged the mounting questions. On February 25, Public Prosecutor Alphonse Dinard Mokondzi appointed an investigating magistrate to oversee an inquiry. “A man has died in a fire; we want to know whether it was of criminal or accidental origin,” Mokondzi told CPJ. The prosecutor said his office took an interest in the case because Ossébi was a journalist and “there is a lot of suspicion.”

Yet much about the investigation remains unclear, including its expected scope and duration and whether its findings will be made public. The investigation itself is hampered because the remains of the rental home were bulldozed and cleared within days of the fire, destroying potential evidence, according to several local sources.

To prepare this report, CPJ interviewed three dozen of Ossébi’s relatives, friends, and colleagues, some of whom declined to be quoted by name, as well as officials in Congo. CPJ also reviewed the few available official documents in the case, along with personal notes Ossébi sent out of the country.

A Focus on Corruption

Ossébi’s death comes amid the run-up to the 2009 presidential election scheduled for July. Incumbent Denis Sassou Nguesso—who seized office in 1979, lost a 1992 election, and stormed back to power in a bloody civil war five years later—is expected to seek re-election although he has not announced his intentions. Several challengers have launched candidacies, including Mathias Dzon, whose headquarters were targeted by unidentified arsonists in late January. That case remains unsolved, according to local journalists.

Ossébi had been a correspondent for the France-based Congolese online newspaper Mwinda since 2006, according to the Web site’s editors. Mwinda—meaning “Light” after a pro-democracy movement founded by the late Congolese politician André Milongo—is among a number of diaspora-run Web sites that closely scrutinize the Congolese government.

A former French colony, the Republic of Congo lies west of the much larger Democratic Republic of the Congo, across the Congo River. Africa’s fourth-leading oil producer, the Republic of Congo has scored poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, an annual assessment of government integrity, ranking 158th out of 180 countries in 2008.

Just four days before the fire, Ossébi wrote a story accusing officials with Congo’s national petroleum authority of improperly negotiating a US$100 billion loan with a French bank, according to CPJ research. Neither the government nor the officials named in the story, including Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso, the president’s son, publicly commented on the story, according to local journalists. Alain Akouala, the government’s minister of communication, declined to comment when contacted by CPJ.

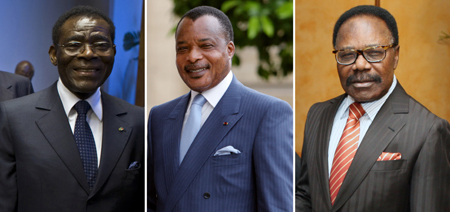

Ossébi also wrote about an unusual lawsuit, filed in France, that questions how the ruling families of the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon assembled extensive private holdings in France. In addition to writing pieces for Mwinda, Ossébi published a blog that regularly described developments in the case. The plaintiffs—Transparency International and a taxpayer of Gabon—allege the defendants acquired large portfolios of real estate, cash, and automobiles by embezzling public funds.

In an interview with the French daily Le Figaro, Congo’s Nguesso denied any impropriety and said the plaintiffs had “manifest intent to harm.” Gabonese presidential spokesman Raphaël Ntoutoume declined comment. Calls made by CPJ to Jeronimo Osa, Equatorial Guinea’s information minister, went unanswered.

The civil complaint, which seeks damages from the three ruling families, is being heard by French magistrate Françoise Desset, who will decide whether the case can go forward.

“Legally speaking, it would be a first,” said Maud Perdriel-Vaissière, a legal adviser with the French international justice network Sherpa, which is providing support to the plaintiffs. Perdriel-Vaissière noted that no foreign citizen or group has yet been allowed to sue a foreign head of state in a French court. A favorable ruling could set a precedent allowing other foreign citizens to sue their leaders in French courts over property in France.

Ossébi was “passionate” about the lawsuit and eager to become a co-plaintiff, according to Bruno Ben Moubamba, a France-based journalist and activist of Gabonese descent who is tracking the complaint closely. Transparency International confirmed Ossébi’s interest in becoming a plaintiff. Enlisting taxpayers from the affected countries can potentially strengthen the case, said Julien Coll, a top official with Transparency International France.

Ossébi’s outspoken stance against alleged government corruption was a bit of a twist, some colleagues said, because his family was considered part of the ruling elite in Congo. His uncle Henri Lopes is the country’s ambassador to Paris; his now-destroyed home was in a neighborhood known as a stronghold of the ruling party. Ossébi seemed to draw some courage from his family standing. “I’m not afraid. … After all, I have an uncle, the ambassador of Congo in Paris, who knows very well the origins of the funds that allow all of these people to make wild expenses,” Ossébi wrote in a December 2008 e-mail to a friend, Serge Berrebi.

Ossébi did not report getting any threats in connection with the case, according to family and colleagues. Others who documented the case in detail or expressed support for it, however, have been subjected to threats and harassment, CPJ research shows

In December 2008, Gabonese military intelligence detained for 13 days five people—Gregory Mintsa, the only individual plaintiff named in the complaint; journalists Léon Dieudonné Koungou and Gaston Asseko; and civil society leaders Marc Ona Essangui and Georges Mpagi. The public prosecutor charged the men with “inciting rebellion against authorities” after they were found with copies of an open letter that Moubamba published on his blog criticizing Gabonese President Omar Bongo’s management of the country’s resources. The case is pending. In March 2008, Gabon’s state-run National Communications Council suspended Tendance Gabon for three months after the private newspaper reprinted a report on Bongo’s holdings in Paris, according to local news reports. The original story appeared in Le Monde.

In France, exiled Congolese dissident Benjamin Toungamani said a series of telephone threats forced his wife to withdraw her name from the lawsuit. Toungamani heads a Europe-based exile group called the Congolese Platform against Corruption and Impunity; his wife is a Congolese taxpayer and, thus, could have been valuable to the case as a co-plaintiff. Toungamani had discussed the case in an extensive interview published in Mwinda just days before the fire.

Coincidentally or not, a fire was reported at Toungamani’s home in the north-central city of Orléans on the same night as the blaze that destroyed Ossébi’s house. Toungamani, who was home at the time but unharmed, said an insurance investigator traced the origin to a short circuit in a washing machine. Nonetheless, he asked police to investigate the matter.

Transparency International has spoken out against the reprisals. Coll said the organization is working with others to develop ways to strengthen protections for people who try to combat corruption.

Overall, the lawsuit has drawn little media attention in the three African countries. In Equatorial Guinea, one of the world’s most censored nations, virtually nothing has been reported. Coverage in the Gabonese press has been heavily self-censored since last year’s suspension and arrests. In Congo, Ossébi was one of the few journalists stationed in the country who wrote about the allegations.

‘Fuzziness’ Surrounds a Death

In Brazzaville, fire investigators did not interview Ossébi while he was in the hospital, although the journalist did recount the circumstances to a friend. Joe Washington Ebina, a businessman and childhood friend of Ossébi, told CPJ that the journalist said he was watching the living room television when he heard a commotion in an adjoining room. When he opened the door, Ossébi told his friend, he was knocked to the floor and badly burned by flames. Ossébi said he crawled on his hands and knees out of the home before making a failed effort to return for his housemates, Ebina recounted. Companion Evelyne Koma and her two children, Lourd Sagesse Ockoueret and Madide Ockoueret, were pronounced dead at the scene. Ossébi suffered second-degree burns over 30 percent of his body, according to one of his doctors.

Initial reports, some from Ossébi’s own family, suggested the fire was caused by an electrical problem with the television. Ossébi’s cousin, Ogers, said the journalist told him the television caught fire. Ebina told CPJ, however, that the journalist never mentioned a short circuit or a television problem in several conversations before his death.

Because no one has been able to authoritatively reconstruct the circumstances of the fire, a “real fuzziness” has hung over the case, said local reporter Arsène Séverin Ngouela, who frequently encountered Ossébi at Groupe Négoce International, a cyber-café in downtown Brazzaville.

Fuzziness has also surrounded Ossébi’s death, which occurred nearly two weeks after the fire during a time when the journalist appeared to be recovering. “We were laughing. He was talking. I brought him some fruits. He was eating. For us, he was going to recover,” said Ebina, who visited him regularly. Ossébi even requested a BlackBerry to check his e-mail, Ebina said.

An attending physician, who spoke to CPJ on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss the case, confirmed that Ossébi’s condition was improving and that there were no apparent predictors of a relapse. The physician, noting that burn victims can suffer sudden reversals during recovery, said Ossébi went into severe respiratory distress before dying on February 2.

The death certificate identifies the cause of death as a “cardio-respiratory arrest,” according to the physician. No autopsy was done. The death occurred a day before Ossébi was scheduled to be airlifted to a French hospital for recuperation, according to family members.

“It’s sad because [Ossébi] was someone who took part in his own way in the debate of ideas,” Congolese Communications Minister Akouala told CPJ in February. Patrick Okamba, director of Brazzaville’s International Press Center, remembered Ossébi as an avid reader of newspapers who enjoyed critiquing their coverage while sipping espresso at La Mandarine, a cafe in downtown Brazzaville. Patrick Eric Mampouya, a France-based political blogger and activist told CPJ that Ossébi’s activist journalism inspired him to start a blog and an e-mail newsletter.

The magistrate appointed to look into the case, Jean Michel Opo, ordered police to form a commission to determine the cause of the fire. Depending on the findings, Opo told CPJ that he can recommend the inquiry be pursued further, with the potential of criminal charges being brought, or he can urge that the case be closed. Asked whether the findings will be publicly released, Opo told CPJ that the process was protected by judicial confidentiality.

Questions involving the fatal fire at Ossébi’s home have gone largely unexamined in the domestic press. Several journalists told CPJ they fear digging too deeply. Friends say they, too, don’t want to ask many questions. “I don’t want to talk about Bruno’s death, particularly on the phone,” one associate told CPJ. Citing fear of reprisal, he asked not to be identified. “I don’t want it to cost my life.”

Mohamed Keita is CPJ’s Africa research associate. Sarah Turbeaux is a consultant for CPJ’s Africa program.

CPJ’s recommendations to the government of the Republic of Congo:

- Based on unresolved questions about the fire and Bruno Ossébi’s death, we call on the Republic of Congo’s public prosecutor to pursue all leads in investigating the case, including possible criminal motives linked to Ossébi’s journalism.

- In the interest of transparency, authorities in Republic of Congo should publicly disclose the results of their investigations into Ossébi’s death.

CPJ’s recommendations to the government of Gabon:

- CPJ calls on the public prosecutor in Gabon to drop all charges against journalists Gaston Asseko and Léon Dieudonné Koungou; civil society leaders Marc Ona Essangui and Georges Mpagi; and Gregory Mintsa. The five are charged with “inciting rebellion” for allegedly possessing an open letter criticizing Gabonese President Omar Bongo’s management of the country’s resources.

- We urge the government of Gabon to halt efforts to censor reports on the misappropriated public assets lawsuit filed by Transparency International.

CPJ’s recommendations to the governments of the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and France:

- CPJ calls on authorities in Republic of Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and France to thoroughly investigate all threats and attacks made against people who have described or commented on the misappropriated public assets case.