Guide for reporting in hazardous situations.

- Covering Conflict

Who is at Risk?

Training

Security Training Courses

Biochemical Courses

Security Training Firms

Security Literature

Funding for TrainingBody Armor

Anti-Ballistic Vests

Helmets

Purchasing Body Armor Protective Gear Companies

Biochemical Equipment

Armored VehiclesVaccinations and Health Sources

First-Aid Kits

Medical Identification

Medevac - Reporting in Hostile Terrain

Staying in Touch

Minimizing Risk in Conflict Zones

Comportment

Clothing and Culture

Theft

Weapons

Credentials

Language SkillsSexual Aggression (added June 7, 2011)

Embedding with Combatants

Rules of War

Captive Situations

Stress Reactions - Readings and Resources

Suggested Articles

Support Resources

Acknowledgments

Comments and Feedback

CPJ is extremely grateful to the Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation, CNN, and the Gannett Foundation whose generous support for CPJ’s journalist security program made the publication of this handbook possible.

Click here to download PDF (Adobe Acrobat) version of this document. Best quality for printing and most convenient format for e-mailing.

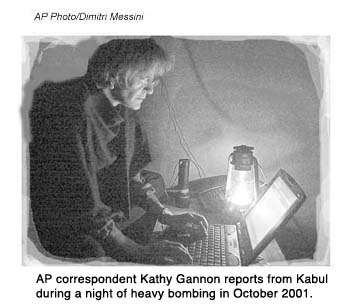

In the early months of 2002, Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl was abducted and executed by his captors while pursuing a story about Islamic militants in Pakistan. The kidnapping, which came only weeks after eight reporters were killed covering the conflict in Afghanistan, was a terrible reminder for journalists around the world of their vulnerability.

In the aftermath of Pearl’s murder, veteran journalists–including the most seasoned war correspondents–began examining their own routines: Could they have suffered Pearl’s fate? What can they and their media organizations do to make their work safer? How should they respond in an emergency? Are there new security issues for those reporting on terrorism, as Daniel Pearl was, in the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington?

At the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), we asked ourselves the same questions.

CPJ was founded more than 20 years ago to fight for the rights of journalists to report the news freely. We do so primarily by using journalism to advocate on behalf of our colleagues: We document individual press freedom abuses; produce daily news alerts and send formal protest letters; publish a biannual magazine, Dangerous Assignments, and an annual survey, Attacks on the Press. We also issue special reports and carry out advocacy and research missions to countries where journalists are confronting serious abuses. Through our work, we have acquired considerable expertise about the physical dangers that journalists confront.

Over the years, CPJ has also offered advice to journalists going into risky situations. For instance, 10 years ago, CPJ published a “survival guide” for journalists covering the violent breakup of Yugoslavia. But since then, much has changed in the world of war correspondence. The proliferation of satellite telephones and other technology has greatly increased the number of journalists covering conflicts while intensifying the competitive pressures that can push them to take unwarranted risks. Media companies increasingly send their news teams to special security training courses that were virtually unknown a decade ago. Greater awareness of the effects of posttraumatic stress has encouraged programs to help war journalists cope after covering wars or other tragedies.

But far too many journalists still cover conflicts without proper preparation–adequate health insurance or training for dangerous encounters, for example. This guide should be read not just by those in the field but also by the media managers who send journalists on dangerous assignments. Those managers should treat the safety of their journalists as paramount. This means discouraging unwarranted risk-taking, making assignments to war zones or other hostile environments voluntary, and providing proper training and equipment for those assignments.

With this handbook, we hope to give journalists and media managers a basic overview of security issues. Readers will find links throughout the text to valuable resources, as well as to suggested readings. While some topics are covered in depth, others involve specific skills that can only be developed through comprehensive training. This report also includes information to help news gatherers obtain training, equipment, and insurance policies. Additional information on safety principles and practices is being developed by a new International News Safety Institute, whose members include CPJ and other press freedom organizations, as well as media companies.

No set of principles, no training course, and no handbook like this one can guarantee any journalist’s safety. Indeed, as we worked with editors, reporters, and others to compile this guide, we heard frequent concerns that some journalists might gain a false sense of security from training courses or safety manuals.

So it’s worth stating again: This handbook and the resources and ideas presented here can help minimize risks but can never guarantee safety in a given situation.

Journalists in dangerous situations must constantly re-evaluate risks and know when to back down. As Terry Anderson, CPJ honorary co-chairman and former Associated Press Beirut bureau chief, who was held hostage for nearly seven years in Lebanon, has said: “Always, constantly, constantly, every minute, weigh the benefits against the risks. And as soon as you come to the point where you feel uncomfortable with that equation, get out, go, leave it. It’s not worth it. There is no story worth getting killed for.”

| Two cautions about this guide: From its years of research, CPJ recognizes that the journalists who are most at risk are often local reporters. They, and their news companies, often cannot afford body armor or expensive training courses. Some of them live with daily risks, different from the risks addressed in this handbook. Some of them are also employed by foreign media companies. CPJ strongly urges all media companies to ensure that journalists and others working for them in conflict zones (including local free-lancers, stringers, and fixers) are properly equipped, trained, and insured.

Through extensive research and reporting, CPJ staff have compiled the information presented here. We welcome your feedback. Any suggestions, comments, and updates to this report may be sent to [email protected]. |

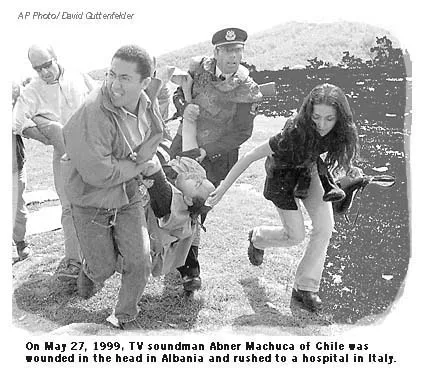

During the last decade, CPJ has compiled a list of 366 journalists who have been killed while carrying out their work. An analysis of this list gives some sense of the kinds of journalists who are most vulnerable to physical attack.

While conflict and war have provided the backdrop to much of the violence against the press over the last decade, the vast majority of journalists killed since 1993 did not die in cross fire. Instead, they were hunted down and murdered, often in direct reprisal for their reporting. In fact, according to CPJ statistics, only 60 journalists (16 percent) died in cross fire, while 277 (76 percent) were murdered in retribution for their work. The remaining journalists were killed in conflict situations that cannot be described as combat–while covering violent street demonstrations, for example.

Since 1993, CPJ has recorded only 21 cases in which the person or persons who ordered a journalist’s murder have been arrested and prosecuted. That means that in 94 percent of the cases, those who murder journalists do so with impunity. Many times, journalists were murdered either to prevent them from reporting on sensitive issues, such as corruption or human rights abuses, or to punish them after they had done so.

In 23 cases since 1993, journalists were kidnapped–taken alive by militants, criminals, guerrillas, or government forces–and subsequently killed. A handful were held for ransom, but most were kidnapped for political reasons.

While the killings of U.S. journalists generate intensive media coverage in the United States, they are not very common; of the 366 journalists killed in the last decade, only 13 were Americans. In fact, most of the journalists killed were local journalists who were murdered in their own countries. But since Daniel Pearl’s murder, U.S. and other Western journalists feel a heightened sense of risk, and there is evidence that today they are more likely to be targeted as journalists. This is the same kind of risk, unfortunately, long faced by journalists around the world.

The murders of dozens of journalists around the world each year receive little attention and often go unpunished. For example, the May 13, 2002, murder of Edgar Damalerio, an outspoken radio reporter on the Philippine island of Mindanao who was gunned down after reporting on corruption by local officials, remains unsolved even though eyewitnesses have clearly identified the gunman. A month later, in a slum outside Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian television reporter Tim Lopes was abducted and executed while reporting on drug traffickers involved in the sexual exploitation of minors. In both cases, these murders received scant international attention.

One of the most important skills that journalists can learn is how to protect themselves and each other in the field. Several companies offer “hostile-environment training” tailored for journalists; hundreds have taken these courses in the last few years, and many who finish the week-long sessions say they are extremely valuable. Even correspondents with years of experience covering dangerous assignments say they learn much from the courses, which are usually taught by former military personnel.

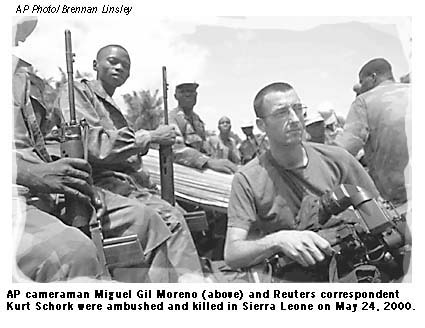

But even the best training cannot guarantee survival, as illustrated by one of the most dramatic cases documented by CPJ in recent years:

But even the best training cannot guarantee survival, as illustrated by one of the most dramatic cases documented by CPJ in recent years:

In May 2000, foreign correspondents around the world were shocked by the deaths of Kurt Schork of Reuters and Miguel Gil Moreno de Mora of Associated Press Television News, who were killed in Sierra Leone while driving two vehicles with Sierra Leonean army soldiers onboard. Rebels ambushed the vehicles, killing the two journalists instantly, along with several of the soldiers.

Schork and Moreno were two of the most experienced war correspondents in the business, described by colleagues as savvy and careful in combat situations. Schork had also completed a hostile-environment training course for journalists. But the surprise attack gave neither correspondent the chance to use his knowledge; they were hit immediately.

Two other Reuters journalists were with them, however, and both survived. Yannis Behrakis, a veteran photographer, and Mark Chisholm, an experienced cameraman, were not hit in the initial gunfire and managed to flee the cars to escape into the bush. Once in hiding, “Behrakis smeared himself with mud and leaves to blend into the terrain as the rebels looked for survivors … within 15 feet of him,” reported Peter Maass in a lengthy article on the incident in the now defunct media watchdog magazine Brill’s Content. Behrakis, who served for two years as a soldier in Greece before becoming a journalist, credited training that he received from the British firm Centurion Risk Assessment Services Ltd. with helping to save his life.

Centurion, along with AKE Ltd., is the oldest private firm to offer specially designed security training courses for journalists. Since the 2002 murder of Daniel Pearl, several more firms based in the United Kingdom and the United States have begun offering security training courses specifically for journalists.

While there is no substitute for experience, training helps. Students in these programs spend about half of their time in the classroom and the other half applying their lessons in field simulations. The simulated exercises are conducted in groups, allowing individuals to test and improve their ability to cooperate with others under emergency conditions.

The central focus of such courses is to raise awareness skills. For example, journalists learn how to listen for the trajectory of bullets, to evaluate the thickness of a cement or brick wall (and thus its ability to withstand bullets and for how long), to filter sediment from filthy water, and to locate a safe place to stand when covering street demonstrations. Nearly every course includes extensive training in emergency first aid. Such comprehensive programs usually last five days; refresher courses are recommended every three years.

Journalists who may cover a conflict with the possible introduction of biological, chemical, or nuclear weapons should obtain both proper training and gear to cope with such hazards. Several security training firms now offer specific training for this type of warfare.

The following companies offer security training for journalists. CPJ does not endorse any specific firm or course but strongly urges media companies to provide hostile environment training for journalists covering dangerous assignments.

For a list of security training firms, click here

Security Literature

No matter what training course journalists or their employers choose, the most important skill that such classes teach is to be mindful of danger in advance. Training manuals exist, but actual hands-on training is preferable.

The U.S.-based relief agency World Vision sells a journalist’s security manual that covers many of the same topics that are dealt with in any comprehensive security training course. The manual can be purchased at http://www.echonet.org/shopsite_sc/store/html/WorldVisionSecurityManual.html

Centurion also offers portable and comprehensive manuals, including “Hostile Environments and Emergency First Aid” and “A Guide to Biological and Chemical Warfare.”

The fee for a five-day training course in either conventional or unconventional hazards exceeds US$2,000. The Rory Peck Trust, which was established in the name of the free-lance cameraman killed in cross fire while covering the October 1993 coup attempt in Moscow, offers a limited number of grants distributed through the Rory Peck Awards. The grants are available to free-lance journalists and subsidize about half the cost of security training. Also, the Reuters Foundation has in the past helped subsidize the costs of such training for some free-lance journalists, and it continues to do so on a case-by-case basis.

The most important thing to remember about body armor is this: Bulletproof vests are not bullet proof. Body armor may stop some projectiles, but one can still suffer serious injury or die as a result of the blunt trauma inflicted by high-caliber or high-velocity bullets. Journalists should consider in advance whether they may require body armor, and what kind or level of protection they may need.

Body armor is primarily categorized according to a six-level system of threats that was developed by the U.S. National Institute of Justice.. Most manufacturers use this system to rate body armor.

Also remember: Protective gear must be properly maintained. Anti-ballistic ceramic plates can crack if dropped or mishandled. Kevlar vests and other gear must be kept dry. Centurion provides tips for care on its Web site.

One risk of wearing body armor is that it tends to be bulky and conspicuous. In a few places, such as Colombia, journalists say they avoid wearing such armor for fear of being mistaken for drug enforcement officials. Body armor is also relatively heavy, and in hot climates it can slow down the wearer.

Nonetheless, body armor is highly recommended in combat zones, including the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Afghanistan, where both cross fire and attacks on journalists are common. And body armor is always recommended wherever there may be shrapnel.

Each type of body armor is designed for a specific purpose. Some are designed to guard against knife attacks, which may be recommended when covering large street demonstrations. Other vests are manufactured to protect against short-range gunfire, which may be recommended for journalists facing the possibility of a targeted attack and for protection against shrapnel from hand grenades or mortar bombs.

Only ceramic or metal plates inserted into the center of the jackets will stop automatic or high-powered rifle fire. But keep in mind that there are special armor-piercing bullets that can penetrate ceramic and metal plates, and even with such plates worn in front and in back, only a portion of the body is protected.

Body armor prices vary depending upon protection level, weight, and durability. Journalists covering any military environment should use nothing less than a level III vest, as outlined by the U.S. National Institute of Justice.

Journalists working in conflict zones should also consider wearing combat helmets, which provide effective protection from flying shrapnel. A helmet, however, will not stop a round fired by a military assault rifle.

Helmets shaped like baseball caps and designed for protection against riots, rock throwing, and similar unrest are available through special order by calling Centurion in the United Kingdom at +44 (0) 1264-355255 or +44 (0) 7000-221221.

Journalists should shop carefully when purchasing body armor. Most vests useful for covering violent street activity (offering protection mainly in case of a stabbing) are under US$350. Vests designed to stop most handgun bullets cost about US$500. Vests rated for work in military zones cost from US$600 to US$2,000.

While most vests are made of Kevlar, Spectra, which floats in water, is becoming increasingly popular. (Even though Spectra floats in water, the vests deteriorate in water. Only special Spectra vests that are designed for military divers will not deteriorate in water. NP Aerospace also makes special anti-ballistic flotation vests designed for prolonged use in water.)

As for inserted plates, although ceramic plates are more expensive than steel ones, they tend to weigh less and are more likely to stop projectiles safely. Steel plates have a tendency to deflect projectiles upward toward the face or head.

NP Aerospace which has designed a jacket for journalists, produces one of the lightest ceramic plates currently available on the market. Its jackets for journalists come with a notebook pocket, along with an option for additional pockets and nonslip shoulder pads for camera operators.

If buying used body armor, always inspect it carefully for damage, especially bullet marks. Once a vest is fired upon, it must be discarded since it can no longer offer full protection.

The Web site run by the French firm Sema offers several useful images of different kinds of body armor, including three types recommended specifically for journalists.

For journalists based in the United States, Zero G Armorwear lists retailers of body armor throughout the United States on its Web site, http://www.bodyarmor.com. For journalists outside the United States, Zero G Armorwear has another site, http://www.safariland.com, listing retailers of body armor in many countries.

In addition to acquiring the right level of protection for a particular situation, journalists should also make sure that the vest or jacket fits properly. The U.K.’s Vest Guard offers a useful diagram for measuring oneself for body armor

For a list of companies that sell protective gear, click here

News gatherers working in areas where biological or chemical weapons may be used face additional risks, as noted above under the section titled “Training.” Training alone is not enough; journalists must purchase biochemical protective equipment, which can be even more expensive than the courses. Some television networks and other news gatherers often buy packages of training and gear through Bruhn NewTech Group.. Centurion also offers both biochemical training and gear.

Journalists working in conflict zones may require armored vehicles, and media employers should provide them when requested. During the 1990s, media companies provided their journalists with armored vehicles in the Balkans, and more recently, news organizations have used them regularly in the West Bank. Journalists should keep in mind that even armor-plated vehicles, however, remain vulnerable to attacks by the shoulder-fired Light Anti-tank Weapon (LAW) and anti-tank land mines.

Armored vehicles cost up to three times the price of standard vehicles. Regular vehicles may also be modified to better withstand blasts from land mines or other explosive weapons; however, journalists should seek expert advice to ensure that any such reinforcements are sufficient to withstand blasts.

Besides Land Rover (http://www.landrover.com), which armors vehicles for media companies such as Reuters, these firms also armor vehicles according to customized needs.

For a list of companies that make armored vehicles, click here.

While most journalists from North American and Western European nations have health insurance provided through either their employers or national plans, a surprisingly high number of journalists from Africa, Latin America, and Asia work without any insurance. Journalists from many less developed nations tell CPJ that health insurance in their countries is rarely available. In such cases, journalists who are injured, even on the job, may or may not be able to rely on their news employers to cover their health care and related costs.

Even staff journalists from North America and Western Europe should review their employers’ health insurance policies to ensure that they are covered in conflict zones. Journalists heading overseas should confirm whether their policies include acts of war and other dangers they may face on assignment. Journalists and their families should also find out what life insurance coverage is in effect. Many large news firms provide medical evacuation, either as needed on a case-by-case basis or explicitly through employment insurance policies.

Staff journalists may also be covered when on assignment overseas through workers’ compensation insurance policies. However, workers’ compensation policies in the United States may vary from state to state, so journalists should review policies prior to departure.

Journalists and their families should ask their employers to provide copies of their insurance policies to review language for war or related situations before going into a conflict zone. Ambiguities should be resolved or at least noted in advance. Journalists covering wars should also keep in mind that, according to the World Health Organization, among the greatest risks to any traveler (including war correspondents) is injury or death by a vehicle, so round-the-clock (not assignment-specific) coverage is worthwhile.

In the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks in New York and Washington, some insurance companies rewrote their policies to expand areas they will not cover. For instance, one Florida-based firm now excludes coverage for: “Treatment and expenses directly or indirectly arising from or required as a consequence of war, invasion, acts of foreign enemy hostilities (whether or not war is declared), civil war, rebellion, revolution, insurrection or military or usurped power, mutiny, riot, strike, martial law or state of siege or attempted overthrow of government or any acts of terrorism.”

Free-lance journalists face particular problems with health insurance. Many such correspondents, even those covering war zones, work without coverage. There are instances where the news organizations they file for have assured them they did have coverage, but later it turned out they did not. In addition, even where coverage exists for free-lancers and stringers, it may not apply on days when they are not filing stories for a news organization. This means that they might not be covered in a traffic accident or other incidents that occur when they are not working on a specific story.

Media companies should recognize their responsibility to free-lancers and stringers covering conflicts and should provide them with coverage equivalent to staff correspondents. Free-lancers and stringers unable to obtain coverage from a media company should contact the organizations listed below to explore their options.

One option is to obtain insurance through high-risk providers such as Lloyd’s of London (+44 [0] 20-7327-1000). U.S. citizens may obtain such policies through the following brokers:

Health Insurance Links

Journalists may also explore other options, including the following:

- Members of the U.S.-based Society of Professional Journalists (http://www.spj.org) may obtain a plan called “Gateway Premier,” which is offered by March Affinity Group Services and is designed for individuals planning to work abroad for at least six months. Fees depend upon the policy terms selected, such as the level of deductible costs. However, while the March Affinity Group Services plan applies to journalists working in war zones, its accidental death or dismemberment coverage does not.

- Reporters Sans Frontières and the French insurance company Bellini Prévoyance, in partnership with ACE Insurance Group, now offers coverage to journalists, photographers, and free-lancers who are residents of countries within the European Union on assignment “anywhere in the world.” The coverage, which is per day, is available in three options that are among the most affordable policies available to journalists (http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=2350).

- The Rory Peck Trust, which promotes safety and security among free-lancers, can advise journalists on insurance policies. Journalists having trouble securing adequate coverage can contact the Rory Peck Trust at http://www.rorypecktrust.org.

Private insurance brokers around the world also help develop policies between news gatherers and insurance firms. Such brokers can arrange for health and life insurance along with special needs, including medical evacuation as required. But some policies provide no coverage for the Middle East, and the prices on polices vary greatly. Available insurance brokers and firms recommended by the Rory Peck Trust and others include:

Health Precautions

Health Precautions

Journalists should check with qualified medical experts to learn what specific immunizations may be needed before traveling. Many countries require visitors to present an International Certificate of Vaccination to customs officials. The certificate, which can be obtained from a physician, should be dated and stamped after each inoculation.

Some countries require journalists to show that they have received a cholera inoculation prior to entry, although many health officials discount the usefulness of cholera shots. Other nations require journalists to submit to an HIV test prior to entry. Journalists who face the possibility of having blood drawn under such conditions should bring their own sterilized needles.

Vaccinations and Health Sources

A general practitioner can either advise journalists on needed vaccinations or refer them to medical services that can provide advice and inoculations, as well as prescriptions for anti-malarial or other recommended medications.

Most physicians will recommend a 10-year tetanus shot for all travelers. Journalists traveling to areas where malaria is prevalent will generally be prescribed prophylactic anti-malarial medication to protect against infection. For some areas, vaccination against polio, hepatitis A and B, yellow fever, and typhoid may also be recommended. The vaccination for hepatitis-B must be planned a half year in advance because it requires three inoculations over a six-month period.

Journalists may consult the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (see “Travelers Health” at for updated, comprehensive, and geographic-specific information on outbreaks, diseases, and recommended vaccinations)

To review health issues, journalists may wish to consult a professional guide such as “Travel Health Companion,” which is distributed by Traveler’s Medical Service of New York and Washington, D.C., and is available from Shoreland Inc.

- Journalists should carry either individual first-aid kits or larger ones, depending on the size of the group with which they are traveling. First-aid kits should, at minimum, include:

- Sterilized bandages in a variety of sizes, including triangular bandages and medium and large dressings;

- Disposable gloves;

- Small plastic airway device or tubing for breathing resuscitation;

- Scissors;

- Safety pins;

- Plastic bags;

- Flashlight or, preferably, a head lamp;

- Adhesive tape;

- Porous tape; and

- Triple antibiotic ointment

Note: Be careful with using basic medications, including aspirin, since some people respond negatively to different drugs.

Journalists may either assemble their own first-aid kits or purchase them from retailers. Many different kits are commercially available through the following sources:

http://www.safety-first.biz/dlx_fak.htm

http://www.first-aid-product.com/226-u.htm

http://www.rescuebreather.com/store/index.cgi?code=3&cat=5

Centurion also designs first-aid kits for journalists depending on size and need. Go to http://www.centurion-riskservices.co.uk and search for “first-aid kit.”

CPJ recommends carrying blood-type identification, as well as information on other medical conditions (i.e. drug allergies, heart murmurs, etc.). In conflict areas, journalists should map out in advance the locations of available medical services along with evacuation routes. Media employers should be prepared to evacuate injured journalists from conflict areas after they receive immediate care in or near the place they were injured, which may involve either a helicopter or vehicle evacuation.

News organizations should provide medical evacuation for journalists in emergency situations. There are many Medevac providers, but only three have an international network capable of providing international evacuations–including evacuation from war zones:

For a list of firms that offer medevac services, click here

Knowing the Geographic Hot Spots

While prudence and caution are always essential, nothing can substitute for knowledge on the ground in a rapidly changing environment. A road that is safe one day could be mined the next. In some situations, traveling in a large group is safer. In others, it might be better to be inconspicuous. Over and over again, reporters tell us that accurate, up-to-the-minute information is essential for making the right decisions.

Although information can quickly become outdated, a number of Web sites offer periodic updates on situations in conflict areas.

For a list of organizations that offer periodic updates to the situation in conflict areas, click here.

II. REPORTING IN HOSTILE TERRAIN

Staying in touch means staying alive. Editors at home should always know your schedule in detail, and at least one trusted individual in the field should know your itinerary in order to enable your colleagues to act quickly on your behalf should you suddenly disappear or fail to return as expected.

In addition, every journalist covering a dangerous story should develop an emergency response contingency plan before he or she begins reporting. Such plans should include these basic features:

- Make sure at least one person–preferably your supervising editor–knows where you are, with whom you are meeting, and when you are expected to return. That person should also know precisely what to do if you do not return or are delayed. If you plan to be gone for more than a day, a plan should be worked out for you to call a designated person (your editor, your spouse or partner, a parent, etc.) every 24 hours. Your failure to call by an appointed time should trigger phone calls to emergency contacts.

- Several people–including colleagues both in the field and back in the office–should be provided with a list of emergency contacts, as well as detailed instructions for how to get in touch with them. The list should include CPJ and other press freedom organizations, which can mobilize international attention on your behalf. Journalists should also carry local emergency phone numbers with them in the field.

Consider working with a partner or with a group wherever possible. In some cases, this means putting aside competitive pressures to collaborate with other journalists. Editors should never push a journalist to visit an area that he or she deems too dangerous; likewise, a journalist should not travel into a dangerous zone without advance clearance from a supervising editor.

In some areas, it may be either difficult or unwise to discuss particularly sensitive matters with editors back home. In many nations, especially countries with active intelligence services, journalists should consider being cautious when using telephones. Moreover, using e-mail to communicate may not be secure either. Some journalists may choose to encrypt their e-mail to communicate with editors and others, but the security of encryption programs remains debatable, and sending encrypted text is likely to raise a red flag to anyone who might be monitoring you. Where Internet access is freely available, journalists and their editors may wish to communicate using generic e-mail accounts such as Yahoo! or Hotmail, which are more difficult to trace. For added security, they may wish to avoid using proper nouns in messages or to develop a code system in advance that can be used to communicate by voice or electronically.

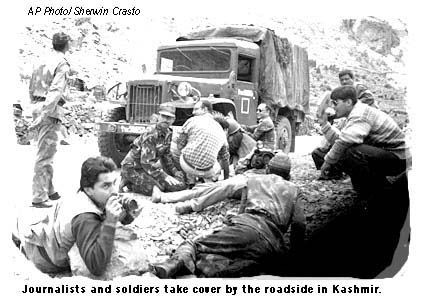

Minimizing Risks in Conflict Zones

How journalists conduct themselves in the field may help save their lives, and the unwritten rules can vary from conflict to conflict. In some situations, for example, it may make sense for journalists to have a high profile, while in others, drawing attention to yourself may draw a hostile reaction from combatants. Talking with seasoned reporters who have covered the region is essential; veteran correspondents are usually generous with advice to newcomers.

The Brussels-based International Federation of Journalists publishes a useful safety manual (http://www.ifj.org/hrights/safetymanual.html) that members of the press should review.

Journalists should always be aware of their behavior in conflict zones and should avoid doing anything provocative. In an increasing number of wars, crossing combatant lines has become more dangerous and difficult, if not impossible. Many combatants and others have challenged the neutral status of journalists in places such as Afghanistan and Colombia; foreigners in both these nations have claimed to be journalists but have allegedly either carried out an assassination or taught bomb-making. CPJ vigorously protests any such impersonations because they increase the risks for all journalists. Moreover, journalists covering conflicts should never represent themselves as something other than what they are: journalists trying to cover a story. They should also avoid being photographed with combatants.

Clothing and Culture

Journalists should be mindful of the kind and color of clothes they wear in war zones. Members of the media should always place prominent labels on their clothing (including helmets) that clearly identify them as press. Journalists who accompany armed combatants–irrespective of whether the combatants are uniformed or not–must consider how their own clothes may look from a distance.

Bright and light colors that reflect a lot of sunlight may make a journalist too conspicuous. But wearing camouflage or military green could make journalists targets. Depending on the terrain, dark blue or dark brown may be preferable. In particular, some photojournalists prefer black because it doesn’t reflect light, but some combatants, especially rebel forces, often wear black.

Of course, journalists should also respect local sensibilities. This includes men and women dressing as decorum may require. Foreign journalists of both sexes should also be aware of practices that could be offensive in some cultures.

Theft

Journalists walking around with protective gear, cameras, or computers should keep in mind that their equipment may be worth a fortune to local residents and should exercise discretion and care with their materials. Correspondents may also wish to separate their money and credit cards and hide them in various pockets or among their gear. Pouches, belts, and other items may be purchased for this purpose at travel stores or on the Internet.

Journalists covering conflicts should never carry arms or travel with other journalists who carry weapons. Doing so jeopardizes a journalist’s status as a neutral observer and can make combatants view correspondents as legitimate military targets.

In some particularly dangerous conflicts journalists have hired armed guards, which can also jeopardize correspondents’ status as neutral observers. Some broadcasters now regularly employ experts from private security firms to accompany their news crews in the field, but these experts are not armed and primarily provide guidance on movements in conflict areas, including large street demonstrations.

All journalists should carry individual press identification, as well as any other event-specific credentials, including military press passes.

Journalists should make sure that they have the ability to communicate in the local language whenever they travel in a hostile zone. Ideally, journalists who do not know the local language should travel with a qualified interpreter who can help them communicate and understand local customs. Journalists should also learn and be able to pronounce the words for “press” or “journalist” in local languages.

Sexual Aggression (Added June 7, 2011)

The sexual assault of CBS correspondent and CPJ board member Lara Logan while covering political unrest in Cairo in February 2011 has highlighted this important security issue for journalists. Dozens of other journalists have reported to CPJ that they, too, had been victimized on past assignments. Both local and international journalists reported being attacked. Most reported victims were women, although men were also targeted, often while in detention or captivity. Journalists have reported assaults that range from groping to rape by multiple attackers.

Being aware of one’s environment and understanding how one may be perceived in that setting are important in deterring many forms of sexual aggression. The International News Safety Institute, a consortium of news organizations and journalist groups that includes CPJ, and Judith Matloff, a veteran foreign correspondent and journalism professor, have each published checklists aimed at minimizing the risk of sexual aggression in the field. A number of their suggestions are incorporated here, along with the advice of numerous journalists and security experts consulted by CPJ.

If you are traveling to a location, especially for the first time, always seek prior advice from colleagues with experience in that locale. Journalists and experts emphasize that situation-specific advice from trusted colleagues is crucial in planning an assignment and assessing risks in the field.

Journalists should dress conservatively and in accord with local custom; wearing head scarves in some regions, for example, may be advisable for female journalists. Female journalists should consider wearing a wedding band, or a ring that looks like one, regardless of whether they are married. They should avoid wearing necklaces, ponytails, or anything that can be grabbed. Numerous experts advise female journalists to avoid tight-fitting T-shirts and jeans, makeup, and jewelry in order to avoid unwanted attention. Consider wearing heavy belts and boots that are hard to remove, along with loose-fitting clothing. Carrying equipment discreetly, in non-descript bags, can also avoid unwanted attention. Journalists should consider carrying pepper spray or even spray deodorant in case they need to deter aggressors.

Journalists should travel and work with colleagues or support staff for a wide range of security reasons. Fixers, translators, and drivers can provide an important measure of protection for international journalists, particularly while traveling or on assignments involving crowds or chaotic conditions, according to experts. Support staff can monitor the overall security of a situation and identify potential risks while the journalist is working. It is very important that journalists use care and diligence in vetting support staff and that they seek recommendations from colleagues. Some journalists have reported instances of sexual aggression by support staff.

Experts suggest that journalists appear familiar and confident in their setting but avoid striking up conversation or making eye contact with strangers. Female journalists should be aware that gestures of familiarity, such as hugging or smiling, even with colleagues, can be misinterpreted and raise the risk of unwanted attention. Don’t mingle in a predominantly male crowd, experts say; stay close to the edges and have an escape path in mind. When traveling, try to choose a hotel with security guards whenever possible, and avoid rooms with accessible windows or balconies. Use all locks on hotel doors, and consider using your own lock and doorknob alarm as well. The International News Safety Institute suggests journalists have a cover story prepared (“I’m waiting for my colleague to arrive,” for example) if they are getting unwanted attention.

In general, try to avoid situations that raise risk, experts say. Those include staying in remote areas without a trusted companion; getting in unofficial taxis or taxis with multiple strangers; using elevators or corridors where one would be alone with strangers; eating out alone unless one is sure of the setting; or spending long periods alone with male sources or support staff. Carry a mobile phone with security numbers, including your professional contacts and local emergency contacts. Keeping in regular contact with one’s newsroom editors and compiling and disseminating contact information for one’s self and support staff is always good practice for a broad range of security reasons. Editors should be assertive in raising security questions about an overall deployment and each planned assignment.

If a journalist perceives imminent sexual assault, she or he should do or say something to change the dynamic, experts recommend. Screaming or yelling for help if people are within earshot is one option. Shouting out something unexpected such as, “Is that a police car?” could be another. Dropping, breaking, or throwing something that might cause a startle could be a third. Urinating or soiling oneself could be a further step.

The Humanitarian Practice Network, a forum for workers and policy-makers engaged in humanitarian work, has produced a safety guide that includes some advice pertinent to journalists. The HPN, part of the UK-based Overseas Development Institute, suggests that international visitors have some knowledge of the local language, and that they use vernacular phrases if threatened with assault as a way to alter the situation.

Protecting and preserving one’s life in the face of sexual assault is the overarching guideline, HPN and other experts say. Some security experts recommend journalists learn self-defense skills to fight off attackers. There is a countervailing belief among some experts that fighting off an assailant could increase the risk of fatal violence. Factors to consider are the number of assailants, whether weapons are involved, and whether the setting is public or private. Some experts suggest fighting back if an assailant seeks to take an individual from the scene of an initial attack to another location.

Sexual assault affects both female and male journalists. Although female journalists constitute the large majority of those assaulted while on assignment, CPJ research shows, sexual abuse can also occur when a journalist is being detained by a government or being held captive by irregular forces. In such instances, both men and women have been targets of abuse. Developing relationships with one’s guards or captors and seeking to stay together with any fellow captured journalist may reduce the risk of all forms of assault. But journalists should be aware that abuse can occur in such circumstances and they may have few options. Protecting one’s life is the primary goal.

News organizations can include guidelines on the risk of sexual assault in their security manuals as a way to increase attention and encourage discussion. While documentation specific to sexual assaults against journalists is limited, organizations can identify places where the overall risk is greater, such as conflict zones where rape is used as a weapon, areas where the rule of law is weak, and settings where sexual aggression is common. Organizations can set clear policies on how to respond to sexual assaults that address the journalist’s needs for medical, legal, and psychological support. Such reports should be treated as a medical urgency and as an overall security threat that affects other journalists. Managers addressing sexual assault cases must be sensitive to the journalist’s wishes in terms of confidentiality, and mindful of the emotional impact of such an experience. The journalist’s immediate needs include empathy, respect, and security.

Journalists who have been assaulted may consider reporting the attack as a means of obtaining proper medical support and to document the security risk for others. Some journalists told CPJ they were reluctant to report sexual abuse because they did not want to be perceived as being vulnerable while on dangerous assignments. Editorial managers should create a climate in which journalists can report assaults without fear of losing future assignments and with confidence they will receive support and assistance.

The Committee to Protect Journalists is committed to documenting instances of sexual assault. Journalists are encouraged to contact CPJ to report such cases; information about a case is made public or kept confidential at the discretion of the journalist.

Journalists have long chosen to travel at different times with combatants on one side or another of an armed conflict. In 2002, the U.S. Defense Department announced that it would allow journalists to “embed” with U.S. military units in any foreseeable war. The Pentagon also began to offer journalists a week of military training with U.S. forces free of charge (attending this training exercise is not necessary to qualify for embedding). While many journalists welcome the Pentagon’s plans to embed them with U.S. forces, others remain wary that the government may use the process to restrict their movements and control their reporting on the ground.

Whether or not to embed with any armed forces is a trade-off in nearly every case. A primary advantage of embedding is that a journalist will get a firsthand, front-line view of armed forces in action. A disadvantage is that journalists will only cover that single part of the story. There are other trade-offs as well. Embedded journalists run the risk of being mistaken for combatants. This is especially true if journalists wear military uniforms when embedding.

If journalists are not embedded with troops and move about independently on the battlefield, they could find themselves being targeted by combatants on all sides of the conflict.

International humanitarian law, which governs the conduct of the parties in an armed conflict, comprises a series of treaties and conventions, including the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocols. Any journalists covering war should understand the basic principles of international humanitarian law for two reasons: first, because journalists covering war should be able to report effectively on violations of the rules of war, including war crimes; second, because a number of provisions of the conventions apply directly to journalists.

An invaluable resource on international humanitarian law is the Crimes of War project, established by journalists Roy Gutman and David Rieff to educate journalists and others about the laws of war. The Web site, http://www.crimesofwar.org, contains articles on current issues, as well as an alphabetized reference guide to dozens of essays on a variety of topics, including the protection of journalists.

The text of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocols are posted by the International Committee of the Red Cross, which is based in Geneva, Switzerland.

Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, journalists accredited by an accompanying military force are considered to be part of the military entourage. If opposing forces capture them, journalists must be treated as prisoners of war (POW) and cannot be charged with crimes, such as espionage, in a civilian court. Under the conventions, POWs must be treated humanely. Their camps must be located away from hostilities, and inmates must be fed, housed, provided with medical care, and given the right to send and receive letters.

The Geneva Conventions were drafted in the aftermath of World War II, when war correspondents generally wore military uniforms and accompanied armed forces. Thirty years later, when the Additional Protocols were drafted and ratified, the nature of war coverage had changed dramatically, and new language sought to address this reality. Article 79 of Protocol I states that “journalists engaged in a professional mission in the areas of armed conflict shall be considered civilians” as long as they take no action to compromise this status, such as wearing a military uniform. Under the rules of war, civilians cannot be deliberately targeted. However, if they are captured, civilians are not entitled to prisoner of war status and may be detained or tried for violating national law (for example, entering a country without a visa).

Thus, under international humanitarian law, journalists have two options. They can accredit themselves as war correspondents and accompany military forces. Journalists intermingled with military forces can potentially be targeted by opposing military forces but are entitled to prisoner of war status if captured. Journalists can also cover a war as a civilian correspondent under the terms of the 1977 Additional Protocols. Journalists, like all other civilians, cannot be deliberately targeted. However, civilians are not entitled to POW status if captured or detained by a hostile government.

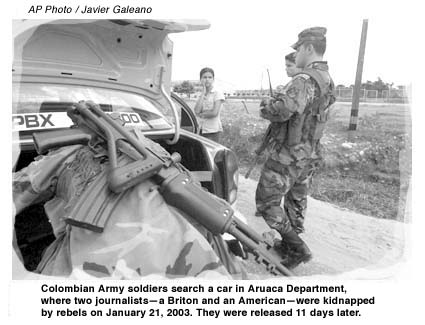

More than 23 journalists have been kidnapped and killed since 1993. The Daniel Pearl and Tim Lopes cases in 2002 underscore this terrible phenomenon. In several cases, notably in Algeria and Turkey, journalists have simply “disappeared” after being taken into government custody.

In several regions around the world, including the Philippines, Chechnya, and Colombia, journalists have been kidnapped for ransom. But journalists are more commonly held hostage or secretly detained for political reasons. Journalists have been beaten, gang-raped, or subjected to other forms of torture, including threats against their children or other loved ones. In both the Pearl and Lopes murders, perpetrators killed each victim to send a message.

Whether or not to try to resist an abduction attempt is a difficult decision that no one is likely to make until it occurs. Kidnapping is an important focus of the hostile-environment training courses now available to journalists, and most security firms encourage journalists to cooperate with perpetrators attempting to abduct or detain them.

Many journalists may think that they are immune to the emotional impact of covering violence, but the evidence suggests otherwise. One 2001 study led by Dr. Anthony Feinstein of the University of Toronto found that war correspondents are more likely to exhibit symptoms of posttraumatic stress than other journalists, and that their reactions are even stronger than those of police officers and firefighters who respond regularly to human crises, and are instead on par with those of military combat veterans. Local reporters covering crime, domestic abuse, or death penalty executions are also at risk.

Stress is a normal reaction to repeated exposure to trauma, especially violence. The reactions are often subtle, including increased irritability, poor concentration, sleep disturbances, emotional numbing, or feelings of insecurity. In most cases such emotions pass, but they are likely to recede more quickly once the individual has discussed memories with either peers or a professional listener.

Talking, writing, drawing, painting, or crying can change the way a traumatic memory is regarded. Child survivors of conflicts from Guatemala to Bosnia have begun to heal by drawing images of attacks. When such articulation is coupled with the opportunity to grieve, it often provides an emotional release, enabling survivors to recall the memory with less pain.

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, which is based at the University of Washington in Seattle–in coordination with the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies–offers journalists a referral service for professional counselors worldwide. U.S.-based press groups like the National Press Photographers Association have also led peer support workshops in coordination with the Dart Center.

Professional counseling is especially important in cases where journalists have been subjected to torture or other forms of physical or psychological abuse, including witnessing the torture of others. The Marjorie Kovler Center for Survivors of Torture is a clinic in Chicago that has developed considerable expertise in treating war refugees.

Below are a few recommended readings that can offer general guidance for any journalist assigned to cover conflict zones:

Press freedom organizations, including CPJ (http://www.cpj.org) and Reporters Sans Frontières, along with such media outlets as the BBC, CNN, ITN, and Reuters have jointly endorsed the general security principles of the International News Safety Institute,, an initiative by the International Federation of Journalists, in cooperation with the International Press Institute.

“Deadly Competition,” an article by Peter Maass in Brill’s Content (September 2000), reports on the Sierra Leone ambush shootings of Miguel Gil Moreno de Mora and Kurt Schork earlier that year.

“Reporting War: Dispatches from the Front” is the text of a speech given by Kate Adie, chief news correspondent of the BBC, who has been reporting on and in conflicts for more than 20 years.

“In the Danger Zone: Weighing Risks” by Michael Parks in Columbia Journalism Review (May/June 2002).

“Staying Alive and Other Tips” by Stephen Franklin in Columbia Journalism Review (May/June 2002).

“Advice for Photographers Covering Demonstrations” is a practical guide available from the National Union of Journalists London Free-lance Branch.

“Danger: Journalists at Work” is a practical safety manual published by the Brussels-based International Federation of Journalists.

“Preparing for Battle” by Sherry Ricchiardi in American Journalism Review (July/August 2002).

A Freedom Forumsponsored panel in 2000, “Setting the Standard: A Commitment to Frontline Journalism; An Obligation to Frontline Journalism,” featured a variety of American and British journalist and their views. The discussion led to the release of a set of safety guidelines for media employers and journalists. A transcript can be read at:

“Out on a Limb: The Use and Abuse of Stringers in the Combat Zone” by Frank Smyth in Columbia Journalism Review (March/April 1992) examines special issues facing free-lancers.

Stories by journalists about the emotional impact of covering wars appear regularly, along with related information about on-the-job stress at http://www.dartcenter.org.

The University of Toronto study of war correspondents, “A Hazardous Profession: War, Journalists and Psychopathology,” by Anthony Feinstein, John Owen, and Nancy Blair, was published in a September 2002 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The results of the study are posted at http://www.dartcenter.org.

Case studies by journalists and experts applying the rule of law to conflict situations are available online at http://www.crimesofwar.org.

Journalists working in hostile environments may turn to many organizations for various forms of support. Below is a list of organizations and how to contact them.

The International Committee of the Red Cross helps detainees in conflicts, including journalists. The main number in Geneva, Switzerland, is (41) 22-734-6001. The emergency after-hours number during weekdays is (41) 79 217-3204 and during weekends is (41)79 217-3285. The ICRC hotline may also be reached through e-mail at [email protected].

To report attacks against journalists or to review previous cases, visit CPJ’s Web site or call or write:

Committee to Protect Journalists

330 Seventh Avenue,12th floor

New York, NY 10001

Tel. 212-465-1004

Fax: 212-465-9568

[email protected]

Journalists can also report attacks involving journalists or review previous cases by contacting Reporters Sans Frontières.

Reporters Sans Frontières

5, rue Geoffrey-Marie

75009 Paris, France

Tel: (33) 1 44-83-84-84

Fax: (33) 1 45-23-11-51

[email protected]

This report was written by Frank Smyth and researched by Kristin Neubauer and Benjamin Duncan.

Frank Smyth is CPJ’s Washington, D.C., representative and journalist security program coordinator. He has reported for CBS News, The Economist, The Village Voice, and other publications and has covered conflicts in El Salvador, Colombia, Rwanda, Sudan, and Iraq. In 1991, just after the Gulf War, Iraqi authorities detained him for 18 days. He is a contributor to Crimes of War: What the Public Should Know, edited by Roy Gutman and David Rieff.

Kristin Neubauer is a free-lance journalist and producer for Reuters Television in Washington, D.C.

Benjamin Duncan is a congressional reporter with Capitol Pulse based in Washington, D.C.

Many colleagues and experts contributed to this report. CPJ wishes to thank the following for their invaluable input: Marcio Aith, Rosental Calmon Alves, Terry Anderson, Oscar Francisco Ayala-Silva, Audrey Baker, Ana Baron-Supervielle, Yannis Behrakis, Phil Bennett, Colin Bickler,Jeremy Bigwood, Elaine Bole, Nora Boustany, Dave Butler, Tina Carr, Analya Cespedes, M. Kasim Cindemir, Carolyn Cole, Neal Conan, Chris Cramer, John Daniszweski, Bob Drogin, Douglas Farah, Linda Foley, Pamela Glass, Gustavo Gorriti, Roy Gutman, David Handschuh, Jay Horan, Kathleen Jackson, Sally Jacobson, Steven Jones, Stephen Jukes, Andrew Kaine, Predrag Kosovic, Olga Krupauerova, Michael J. Limatola, Hilary Mackenzie, Duncan March, Adam Ouloguem, John Owen, William Parra, Paul Rees, Monica Riedler, Bruce Shapiro, John Siceloff, Alison Smale, Philip A. Tazi, Martin Turner, Leonard Venezia, Sandra Vergara, Aidan White, and David Wood.

Any suggestions, comments, and updates to this report are welcomed and should be sent to [email protected].