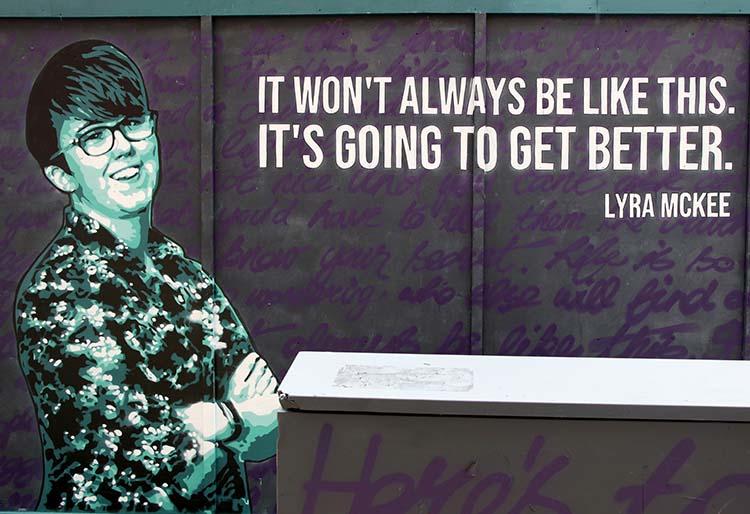

Leona O’Neill was reporting in Londonderry’s Creggan estate on April 18, 2019, the night Lyra McKee, 29, was struck by a bullet. Considered a rising star in the British and Irish media, McKee was the first journalist to be killed in Northern Ireland since 2001, CPJ noted at the time.

McKee’s death shows the risk of covering unrest in Northern Ireland, where CPJ has also reported death threats against reporters. The group that claimed responsibility for McKee’s death calls itself the New IRA (Irish Republican Army) and represents the “most severe paramilitary threat facing Northern Ireland,” according to Foreign Policy magazine. Research from UNESCO published in 2019 highlights the risk of conflict returning to Northern Ireland after it officially ended with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, 21 years before McKee was killed. Police continue to investigate the shooting; two men have been charged with rioting and arson offenses, though not in direct connection with McKee’s death, according to the BBC.

O’Neill, a journalist for more than two decades, writes for The Belfast Telegraph newspaper and works as a producer for Al-Jazeera TV. A blogger accused her of fabricating McKee’s death, sparking a torrent of online abuse against O’Neill, according to the Guardian.

O’Neill spoke to CPJ about her experiences and the changing nature of journalist safety in Northern Ireland. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Before Lyra McKee’s death, what was the press freedom situation like in Northern Ireland?

The press in Northern Ireland enjoy a lot more freedom than in other countries. We are not censored in our day-to-day work, but a lot of reporters have been issued death threats by paramilitary organizations because of their work.

I have lived with a number of paramilitary threats over the course of my career. In more recent years, I have been threatened online. Threats intensify during times of conflict here, and are often intertwined with parades and other issues concerning identity. Threats and hostility have become a part of the fabric of being a journalist in Northern Ireland, sadly.

The terrorism threat level is severe in Northern Ireland at the moment, and due to the fact that dissident republicans have stepped up their attacks, I often do not feel safe covering certain stories. Police officers are a target, and because they are often at the scene of events which are news stories, there is a danger of being caught up in any potential attack, as Lyra was.

Can you tell me about the night of April 18, 2019?

I was told that there was an operation—a bomb alert—in Creggan, a large nationalist housing estate where police are often attacked. I went to the scene to cover it as normal. There was a heavy police presence. Crowds had gathered and I was filming what then developed into serious rioting. Youths were throwing stones, bottles, and petrol bombs at armored police vehicles.

People had come out of their homes to watch. There were children walking around, teenagers standing in the street filming for social media. There was little sense of danger at that stage.

Cars were hijacked and set ablaze at the bottom of the street. A shot rang out and I ran for cover. A dissident republican gunman was firing up the street at us, targeting the police vehicles. A bullet hit Lyra, who had been standing beside a police Land Rover. There was screaming and chaos as people realized what had happened. My friend put his coat under Lyra’s head as she lay on the ground. I called an ambulance.

Police officers placed Lyra in the back of their vehicle and drove through the burning street barricades to the hospital, where she tragically died.

You received online abuse in the aftermath of Lyra’s death. How did that affect your ability to do your job?

The day after I escaped death in a shooting and had witnessed a colleague being murdered, I was faced with hundreds of messages calling for me to be attacked, stabbed, arrested, set on fire, that my children would burn in Hell, that I was a liar, and that I made up what happened for personal gain.

This went on for months. I had to contact the police about several people who seemed to be obsessed with causing me harm and had solicited donations to “wage war” on me.

Eight months later, the harassment is still happening, but to a lesser extent. Some messages tell me I am not welcome in certain areas of my city.

It impacted my mental health. I became anxious and hyper-vigilant for a time as I dealt with PTSD, not only from the traumatic event I had been a part of, but the tsunami of abuse afterwards. I carried on working and went to trauma counselling, but at times it was extremely difficult to do my job.

What kind of impact has Lyra’s death had on the community of journalists in Northern Ireland?

The journalist community banded together in the wake of Lyra’s death. The National Union of Journalists rallied the journalist community. The Belfast Telegraph were very supportive of me also, which as a freelancer, was very appreciated.

Has Lyra’s death made you rethink your personal safety, especially while covering unrest?

I have rethought my personal security. Depending on the situation, I will wear protective clothing and assess every scenario for risks. In the past I might not have. I haven’t had any safety training during my career, mainly because I am a freelancer. I have also covered dozens of riots.

Journalists in Northern Ireland may have become complacent over the years.

For information on journalist safety, see CPJ’s Emergencies Response Team Resource Center.