The Chavez administration pulls a broadcast license as it asserts media muscle

By Carlos Lauria and Sauro Gonzalez Rodriguez

| CARACAS, Venezuela |

Posted April 24, 2007

|

|

|

A scantily dressed Blanca struck a seductive pose and rubbed her foot against Daniel’s muscled leg when–surprise!–her ex-husband, Esteban, burst into the room to start an invective-hurling, furniture-jostling brawl. “How to Get a Man,” a soap opera-style drama on Radio Caracas Televisión, or RCTV, Venezuela’s oldest private television station, was filling the nation’s TV screens with its popular tales of lust and love on this January afternoon.

One of those screens was in the office of Willian Lara, Venezuelan minister of communication and information, whose gaze CPJ’s Recommendations

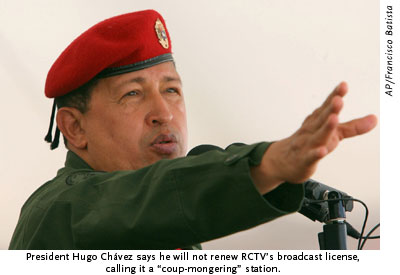

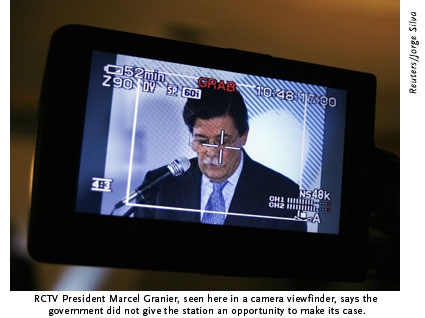

CPJ calls on the Venezuelan government to implement the following recommendations. Barring a last-minute reversal–something RCTV is pursuing in court–the government says it will not renew the station’s license to use the public airwaves when the term expires on May 27. The license–or concession, as it is known in Venezuela–would be the first to be effectively pulled from a private broadcaster by the government of President Hugo Chávez Frías. As Chávez continues to move toward what he and his supporters call “socialism of the 21st century,” his administration’s decision could have broad implications for free expression in this South American nation of 26 million. Officials from the president on down have accused RCTV of violating the constitution and the country’s broadcast laws–not to mention, they say, collaborating with planners of a 2002 coup against Chávez. But a three-month investigation by the Committee to Protect Journalists has found that the government failed to conduct a fair and transparent review of RCTV’s concession renewal. Instead, CPJ found, the evidence points to a predetermined and politically motivated decision. Chávez himself announced the decision in a December 28 speech, in which he said the government would not renew the “coup-mongering” RCTV’s license. In the months before and after the announcement, the government held no hearings, followed no discernible application process, and provided RCTV no opportunity to respond to assertions made by top officials in press conferences, speeches, and interviews.

Yet the White Book, published by the Ministry of Communication and Information, does include 45 pages of documents outlining alleged RCTV violations of broadcast laws. The citations on their face appear to be minor; the book offers no means to gauge their severity, to judge them against established government standards, or to compare them against the records of other broadcasters. The government, for example, cited RCTV for covering a well-known murder case in a “sensational” manner and for showing alcohol consumption during a professional baseball game. The government also chided the station for calling the Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television–which sets broad content restrictions on broadcasters–as the “content law” in its news broadcasts. Other accusations against RCTV–such as promoting “pornography”–are not cited in the book even though they were made publicly by top officials. Founded in 1953, RCTV has long been known for its strident opposition views, but it disputes the government’s assertions of illegality and says the Chávez administration is engaging in political retaliation and suppression of critical news coverage. RCTV said it was never penalized for any violation, only warned. By contrast, RCTV said, the government left intact the licenses of other stations that have been penalized. This record, CPJ found, reflects an arbitrary and opaque decision-making process that sets an alarming precedent and casts doubt on Venezuela’s commitment to freedom of expression. The threat of losing access to the airwaves hangs over dozens of other television and radio stations whose concessions have also come up for renewal, prompting some news outlets to pull back on critical programming. The RCTV case also comes as the Chávez administration is moving aggressively to expand state media and amplify its voice. The government says it will take over RCTV’s frequency with plans to make it a public broadcasting channel. Chávez has interpreted his landslide victory in the December 3, 2006, presidential election as a mandate to accelerate his socialist agenda. He immediately called on the political parties that make up his ruling coalition to dissolve and fold into one, and he recommended the appointment of a commission to reform the constitution–to include, possibly, indefinite presidential re-election. In January, the National Assembly–its seats filled entirely with pro-government legislators since the opposition boycotted the 2005 legislative elections–unanimously approved a law granting Chávez power to legislate by decree for 18 months in key areas such as national security, energy, and telecommunications. Since Chávez first took office in 1999 promising to implement what was widely considered a reformist, nationalist agenda, he has developed a highly contentious relationship with the press. Although he was elected in 1998 with the support of some media outlets, Chávez soon broke ties with them. As his agenda became more radical (or authoritarian, in the view of media executives), private media outlets took an openly partisan role, actively seeking his ouster and embracing the positions and language of his opponents. Some analysts say that private media, particularly television broadcasters, contributed to the country’s polarization with one-sided coverage of the political crisis that overtook Venezuela from 2001 to 2004, and with their hostility toward the government and its supporters. “Television turned into one of the elements that accentuated the polarization of the country; a powerful sector used the stations to overthrow the government,” said Teodoro Petkoff, editor of the Caracas-based daily TalCual and a leading opposition politician. The April 2002 coup against Chávez was a watershed for the administration, according to Marcelino Bisbal, a professor at Universidad Católica Andrés Bello who has written extensively on press issues in Venezuela. That was the moment when Chávez realized the government’s communications apparatus–composed of a radio network, one TV channel, and the official news agency–was at a disadvantage with respect to commercial media. Since the coup, the administration has undertaken an ambitious plan to beef up the government’s communications portfolio. Chávez has used this growing state-owned sector as a government megaphone, stacking its personnel ranks with sympathizers and influencing content to ensure that he receives vast amounts of uncritical coverage. In addition, he has used cadenas–presidential addresses that preempt regular programming on all stations–to counter the private media’s news coverage and to single out individuals for censure, often lashing out at journalists and media owners. His aggressive rhetoric has reinforced hostility toward journalists among his supporters, and officials have repeatedly made unsubstantiated charges linking local journalists to purported U.S. attempts to destabilize Venezuela. From 2000 to 2004, coinciding with peaks of political conflict, scores of Venezuelan journalists were attacked, harassed, or threatened, for the most part by government loyalists and state security forces. The violent animosity has not been one-sided: Opposition sympathizers have attacked or harassed reporters and photographers working for state media. One photographer, Jorge Tortoza, was shot and killed while covering clashes between opposition demonstrators and government supporters that preceded the 2002 coup.

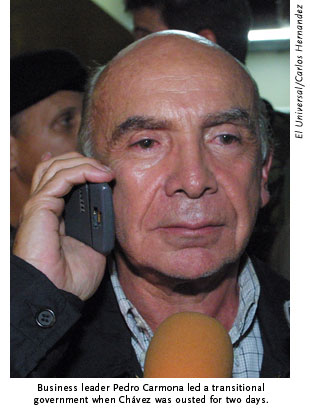

Long before Chávez came to power, other Venezuelan presidents had attempted to silence critical news coverage. Their methods ranged from threats and overt censorship to denials of preferential exchange rates for the import of newsprint. Some media outlets were known to quietly cave in to pressure and accommodate government demands; others denounced those pressures. For instance, after a failed military coup in February 1992–this one led by Chávez, then a lieutenant colonel–at least five media outlets in Venezuela were raided, censored, prohibited from circulating, or had copies confiscated by authorities. Chávez administration officials told CPJ that they pride themselves on promoting free expression. While the democratic period from 1958 to 1998 was marked by media self-censorship and acquiescence to government demands, they said, free speech has flourished under Chávez. “In Venezuela, we are recovering the freedom of expression that until now has been confiscated by large corporate groups. The very moment in which Venezuela is accused of violating freedom of expression is the moment when there is the most freedom of expression,” said José Vicente Rangel, a Chávez ally who served as vice president until this year. For proof of their commitment to free speech, officials note that no journalist has been imprisoned or expelled and that no newspaper or TV station has been seized or suspended during Chávez’s eight-year tenure. “There’s an authentic democracy in Venezuela in the property of media. It’s not true that private media are being smothered,” said Lara, the communication minister. The administration also points to state-supported community media–low-power, limited-range stations that are billed as independent, nonprofit entities serving the communities in which they are based. According to government figures, regulators granted licenses to 193 community radio and TV stations between 2002 and 2006, while the 2007 budget allocates approximately US$1 million for community media. The government trumpets these stations as evidence it supports greater media diversity, but analysts say that much of the programming thus far has been homogeneous and government influenced. At the same time, journalists, media executives, and free speech advocates told CPJ that authorities have sought to marginalize the traditional private press by blocking access to state-sponsored events, government buildings, and public institutions; by refusing to give statements to reporters working for private media; by withholding advertising; by denying access to public information; and by filing criminal defamation complaints. “There are two different perceptions about what a journalist’s job should be, from inside and outside the government, and those perceptions are mutually exclusive. Every time the media reports on government mistakes or acts of corruption, they are accused of becoming involved in politics,” said Gregorio Salazar, secretary-general of the national press workers trade union. All of the journalists and media executives who spoke with CPJ agreed they could express their views but said they risked retaliation in the form of tax harassment, administrative inspections, official silence in response to their requests, and verbal attacks aimed at discrediting them. Executives with the independent channel Globovisión, for example, said that their station had asked the government repeatedly for permission to expand the station’s signal but had received no answer. The print media, which are not covered by the social responsibility law, are less vulnerable to direct government pressure. Instead, newspaper editors told CPJ, they tend to see state advertising pulled in retaliation for critical coverage. “In our business model, we’ve decided that official advertising does not exist,” said El Nacional ‘s publisher and editor, Miguel Henrique Otero. Broadcasting a mix of news, sports, soap operas, talk and game shows, RCTV has long been a leading network in Venezuela. Its weekly satirical program, “Radio Rochela” has been a Venezuelan institution, lampooning politicians well before Chávez was first elected in 1998. The station has also been among those closely associated with the political opposition, actively promoting a partisan agenda and harshly criticizing Chávez. The administration has long reminded RCTV and other private media of their cheering for the April 2002 coup that briefly unseated Chávez, as well as their participation in a failed, opposition-led general strike in late 2002 and early 2003 that sought to force his resignation. Chávez has regularly threatened to review or revoke the broadcast concessions of private TV channels, which the government has labeled golpistas, or “coup mongers,” but whose executives have never been charged with involvement in the coup. The situation escalated in June 2006, when Chávez threatened to block the license renewals of unnamed television and radio stations that were waging “psychological war to divide, weaken, and destroy the nation” as part of an “imperialist plan” to overthrow the government. Days later, Lara announced that the government was legally entitled to refuse license renewals to stations it deemed in violation of the law. Broadcasters, he said, had demonstrated “a systematic tendency to violate” the social responsibility law. After having won re-election, Chávez singled out RCTV in a December 28 address to Venezuelan troops. “There won’t be any new concession for that coup-mongering channel that was known as Radio Caracas Televisión,” Chávez said. “Venezuela must be respected.” That applies to international observers, too, he made plain. When José Miguel Insulza, secretary-general of the Organization of American States, expressed concern that the action was unusual and could have international implications, Chávez publicly called him an “idiot.” Several free speech advocates, some of whom are highly critical of RCTV’s programming, told CPJ that the government was clearly punishing the station for its editorial stance–and that the effect on unbiased reporting would be enormous. They said the non-renewal of RCTV’s concession was a political decision with the thinnest of legal veneers. “My interest is not [defending RCTV chief] Marcel Granier but defending the people who want to follow and watch RCTV’s programming–even if the government finds it annoying,” said Carlos Correa, director of Espacio Público, a nongovernmental organization that promotes free expression and journalism ethics in Venezuela. Lara said the RCTV ruling was not a politically inspired act of retaliation. “The elite always assume they are above the law, above the constitution,” Lara said. “We don’t need any process because their concession is not being revoked; their frequency becomes free after May 27. A TV signal in Venezuela must have a social function–that’s a constitutional mandate.” But licensing, CPJ found, is wrapped in ambiguity and ripe for political manipulation. The government’s White Book says the 1987 broadcast decree and the 2000 Organic Law on Telecommunications form the basis for handling renewals. But neither document spells out in detail the criteria or process by which applications are to be evaluated. RCTV argues that the government ignored one crucial provision of the broadcast decree, which says that current license-holders should be granted preference when they are seeking renewal. The station has pressed a number of other arguments in favor of its concession renewal. Granier, the station president, told CPJ that the National Telecommunications Commission (Conatel), the agency in charge of broadcast concessions, failed to respond to RCTV’s formal application to update the license–first filed in 2002–and thus the concession should automatically roll over. “We are being accused of being golpistas, of pornography, but we haven’t seen one single file containing those accusations so that we can defend ourselves,” Granier said. Indeed, some public allegations made against RCTV went undocumented in the government’s own White Book. Lara, for example, said that the station had violated the social responsibility law by airing shows such as “How to Get a Man” during daytime hours. The law on social responsibility does spell out an array of content restrictions, CPJ found, but it does not explicitly forbid such programs during the daytime hours. A number of other Venezuelan stations, in fact, have similar daytime broadcasts. RCTV has appealed the decision to the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, asking the court to ensure its right to due process and to issue an injunction blocking the government’s actions. Termination of the license could be a devastating blow. In an interview with the daily El Nacional, Granier said the station “lives on its permit to operate broadcast frequencies.” Moving RCTV to cable or satellite does not hold great commercial promise in Venezuela, where only one in five homes has access to such transmissions. Using RCTV’s frequency, the government plans to create a public service channel by allowing independent producers, community and social organizations, and cooperatives, to design programming, said Chacón, head of the newly created Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technology. The government initially said it would expropriate RCTV’s transmitters, antennas, and towers, although Chacón later said it would purchase and install its own equipment. The 2002 coup attempt is central to all discussions about government-media relations. On April 11, 2002, following three days of opposition protests, the government preempted broadcasts by local television stations for a message from Chávez. During the address, private stations continued covering the protests using split screens. Chávez accused the stations of conspiring to overthrow his government and ordered them closed. At around midnight, the president was ousted by a group of high-ranking military officers, and Pedro Carmona, head of the country’s most powerful business group, was appointed leader of the new, military-backed cabinet. News of the coup resulted in protests by Chávez supporters, and within 48 hours military officers loyal to Chávez had reinstated him. During his ouster, the four main private TV channels featured scant coverage of pro-Chávez demonstrations and instead showed cartoons and movies. Many analysts alleged that private media executives had colluded to impose a news blackout, heeding instructions given by Carmona. The executives claimed that they could not cover the story for fear that Chávez’s backers, who had harassed several media outlets earlier in the year, would attack their staff or their offices. No media owner or executive has ever been charged with involvement in the coup. And in a controversial decision, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice ruled that what happened on April 11, 2002, wasn’t a coup d’état at all. Coup or not, it’s had a lasting effect on the news media. Venevisión, RCTV’s main competitor as Venezuela’s top-rated TV channel, appears to have escaped the government’s ire for the time being. Once among the Chávez administration’s favorite targets, Venevisión, led by media mogul Gustavo Cisneros, had opposed the government and championed the opposition’s cause. Officials had previously alleged that Cisneros was a leading figure in the events surrounding the coup. But in June 2004, a private meeting between Chávez and Cisneros, mediated by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center, produced a ceasefire of sorts. “There was a mutual commitment to honor constitutional processes and to support further discussions between the government of Venezuela and the country’s news media to ensure the most appropriate climate for this constitutional process,” the Carter Center said in a statement. Venevisión subsequently removed opinion and news shows that were highly critical of Chávez, and it now focuses almost exclusively on entertainment programming. Today, government officials cite Venevisión as a model of behavior. Venevisión executives did not return messages from CPJ seeking comment on programming. Without RCTV, local journalists and free speech advocates predict there won’t be any national broadcaster left to criticize the government. (Venezuela’s other critical TV station, Globovisión, can be seen as a broadcast channel in metropolitan Caracas and the state of Carabobo only.) The remaining private broadcaster with national reach, Caracas-based Televén, is widely believed to have followed Venevisión’s steps in curbing its criticisms of the Chávez administration. In an October 2005 report, the Peruvian press freedom group Instituto Prensa y Sociedad said Televén had dropped four opinion programs since September 2004. Televén executives did not respond to CPJ’s requests for comment. A report on the 2006 presidential election by European Union observers found yawning gaps in broadcast coverage of the campaign: “The tone of the coverage on Televén and Venevisión was generally not very critical of either of the leading coalitions, but from a quantitative point of view both openly favored the [Chávez] position.” Venevisión, the observers said, devoted 84 percent of its political coverage to the Chávez coalition; Televén, 68 percent. Uncertainty hangs over the concessions of dozens of other broadcasters whose 20-year terms expire this year under the 1987 decree. At various times, telecommunications minister Chacón has suggested that the government would have the right to take over frequencies at some undetermined point in the future. More recently, he’s said that concessions will be renewed for five-year periods. These ominous and shifting standards, journalists say, are certain to dampen critical coverage. As the Chávez administration moves assertively on licensing, it is building its own media structure. Until 2002, the state communications apparatus was composed of the Radio Nacional de Venezuela network, Venezolana de Televisión (VTV), and Venpres, the official news agency. Since then, the government has challenged the private media’s influence through investment in state-owned and community media projects, for which it has budgeted 362 billion bolívares (US$169 million) in the last two years alone. VTV, which had been neglected by previous administrations, received an infusion of technology that allowed the channel to improve the quality and reach of its signal. The government has also invested in new national broadcast and cable outlets and the creation of alternative and community media, including TV and radio stations, newspapers, and Web sites. Since 2003, it has financed the startup of ViVe TV, a cultural and educational television network with nationwide coverage; ANTV, which broadcasts National Assembly sessions on the airwaves and on cable; and Ávila TV, a regional channel run by the city of Caracas.

Telesur is broadcast from Caracas via satellite link, and its signal can be received in Latin America, in most of the United States, and in Europe. Cable systems in a number of Latin American countries have signed agreements to distribute the network’s programming, and in Spain, several small TV stations will carry its news programs. Telesur said it intends to launch its own station in Spain later this year. Last December, Telesur bought Caracas-based broadcast television channel CMT in order to expand its reach beyond cable and satellite subscribers. On February 9, the network began transmitting its signal to all major Venezuelan cities, including Caracas. In the rest of the country, it’s available through DirectTV’s satellite system, cable providers, and community TV stations. In a January 8 interview with the Caracas daily El Nacional, Andrés Izarra, former minister of communications and information and Telesur president, said the Chávez administration is building “information hegemony.” “For the new strategic scenario that is discussed, the struggle that falls in the ideological field has to do with a battle of ideas for the hearts and minds of people,” Izarra stated. “We have to prepare a new plan, and the one we are proposing is aimed at achieving the state’s communication and information hegemony.” He insisted that this hegemony did not mean the end of dissent, and that media not aligned with the government would continue to exist. By expanding state and community media, Lara and other top officials say, the government is fulfilling its constitutional mandate to guarantee Venezuelans’ right to information. Media analysts such as Bisbal say that approach has been self-serving. “For this government,” Bisbal wrote in a 2006 analysis, “information is about creating one sole truth, one sole communication, one sole information, one sole culture.” Without ensuring due process in the RCTV case, the government reinforces that viewpoint. The record shows that, first, a decision was announced, and then a flurry of public allegations made. But thus far, there has been no fair and transparent process whereby evidence could be scrutinized and the station could present its case. Instead, the record reflects the actions of a government motivated by political considerations to suppress critical coverage. Because the broadcast concessions of many radio and television stations are due to expire this year, the RCTV case is forcing other outlets to soften their coverage and rid their programs of critical voices. The Chávez administration appears to be replacing what it considers to be corporate domination of the airwaves with state domination. Carlos Lauría is CPJ’s senior program coordinator for the Americas. Sauro González Rodríguez, CPJ’s former Americas consultant, is a Miami-based journalist. |

||

this day passed over an entire bank of television monitors carrying broadcasts from across Venezuela. It was around 5 p.m. as Lara was meeting his visitors, a time slot that government regulators say should be tailored to family viewing. “Just for this reason,” Lara said, “RCTV doesn’t deserve a broadcast concession.” Though standard dramatic fare by regional standards, such RCTV programs have been assailed as “pornography” by government officials–one of many shifting and often unsupported public accusations made against the station.

this day passed over an entire bank of television monitors carrying broadcasts from across Venezuela. It was around 5 p.m. as Lara was meeting his visitors, a time slot that government regulators say should be tailored to family viewing. “Just for this reason,” Lara said, “RCTV doesn’t deserve a broadcast concession.” Though standard dramatic fare by regional standards, such RCTV programs have been assailed as “pornography” by government officials–one of many shifting and often unsupported public accusations made against the station. In late March–three months after the decision was announced–the government released a 360-page paperback book that sought to explain the decision. Part documentary and part polemic, the White Book on RCTV devotes chapters to corporate media concentration, a history of Venezuela’s broadcast concessions, its view of RCTV’s role in a failed 2002 coup, and what it describes as the harmful effects of concentrated media ownership. The book lays out the administration’s position that it has full discretion on whether to renew the broadcast licenses first granted to RCTV and other broadcasters for 20-year terms under a 1987 decree. Jesse Chacón, a top telecommunications official, said at a March 29 press conference that the RCTV decision was not a sanction against the station but simply the “natural and inexorable” product of the concession’s expiration.

In late March–three months after the decision was announced–the government released a 360-page paperback book that sought to explain the decision. Part documentary and part polemic, the White Book on RCTV devotes chapters to corporate media concentration, a history of Venezuela’s broadcast concessions, its view of RCTV’s role in a failed 2002 coup, and what it describes as the harmful effects of concentrated media ownership. The book lays out the administration’s position that it has full discretion on whether to renew the broadcast licenses first granted to RCTV and other broadcasters for 20-year terms under a 1987 decree. Jesse Chacón, a top telecommunications official, said at a March 29 press conference that the RCTV decision was not a sanction against the station but simply the “natural and inexorable” product of the concession’s expiration. The government’s rhetoric has been accompanied by a legal offensive against the news media. In 2005, the National Assembly drastically increased criminal penalties for defamation and slander while expanding the reach of the penal code’s desacato provisions, which criminalize expressions deemed offensive to public officials and state institutions. The Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television, which took effect that year, has been widely criticized by press freedom advocates for its broad and vaguely worded restrictions on free expression. Article 29, for example, bars television and radio stations from broadcasting messages that “promote, defend, or incite breaches of public order” or “are contrary to the security of the nation.”

The government’s rhetoric has been accompanied by a legal offensive against the news media. In 2005, the National Assembly drastically increased criminal penalties for defamation and slander while expanding the reach of the penal code’s desacato provisions, which criminalize expressions deemed offensive to public officials and state institutions. The Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television, which took effect that year, has been widely criticized by press freedom advocates for its broad and vaguely worded restrictions on free expression. Article 29, for example, bars television and radio stations from broadcasting messages that “promote, defend, or incite breaches of public order” or “are contrary to the security of the nation.”

In July 2005, the Chávez government launched its most ambitious media project to date: Telesur, a 24-hour news channel that officials see as an alternative to CNN. Venezuela owns 51 percent of the channel, while the governments of Argentina, Cuba, Uruguay, and Bolivia own minority stakes. Telesur currently has several news bureaus in Latin America, the Caribbean, and in Washington. It plans to start a news agency and open bureaus in London and Madrid later this year.

In July 2005, the Chávez government launched its most ambitious media project to date: Telesur, a 24-hour news channel that officials see as an alternative to CNN. Venezuela owns 51 percent of the channel, while the governments of Argentina, Cuba, Uruguay, and Bolivia own minority stakes. Telesur currently has several news bureaus in Latin America, the Caribbean, and in Washington. It plans to start a news agency and open bureaus in London and Madrid later this year.