Óscar Martínez knows first-hand the dangers of reporting on crime and gang violence. The co-founder of Sala Negra (Black Room)–an investigative reporting project run by the El Salvadoran new outlet El Faro–says he and his colleagues have been threatened and harassed for their hard-hitting coverage. But, Martínez says, their sources are equally at risk of attack just for talking to the press.

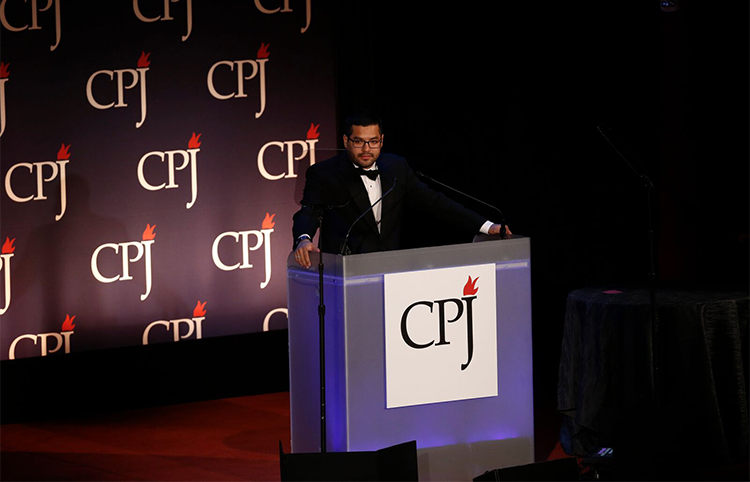

When he was honored with the International Press Freedom Award last year, Martínez told CPJ, “I don’t think we’ve suffered yet even 1 percent of what those who we write about suffer.”

CPJ is committed to improving journalist safety, especially for those reporting in regions where kidnappings and killings are rife. In an interview with CPJ, Martínez said those conversations on safety should go further and that journalists working in dangerous regions need to share their knowledge of risks and advice with those they report on.

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]

You’ve been outspoken on the importance of source protection, including in your acceptance speech at the International Press Freedom Awards. Why is protecting sources so important for journalists in countries like El Salvador?

For those of us who work as journalists in violent regions, the subject of our own safety is something that’s very present. We talk a lot about how to protect ourselves while working, but we leave this discussion about sources in the background. The truth is that we’re lethal weapons for some people.

Imagine that a foreign reporter comes to El Salvador and goes to a gang-controlled area with a police escort. This reporter goes into someone’s house to ask questions, stays there a while–everyone sees it, and then afterwards what happens? This person might be in danger because the gang thinks they said something, that they’re giving some information to authorities. The journalist is gone, but this person is still there.

And yet this issue is something we rarely talk about, even though it’s very common. It doesn’t even appear in most safety manuals … We can’t do our work without our sources, so we have to be able to protect them.

This isn’t to say there isn’t risk for us, too–look at Mexico, where they are systematically killing journalists. If they’re capable of murdering a great, well-known journalist like Javier [Valdez Cárdenas], it’s understandable that people there are afraid. [EDITOR’S NOTE: Valdez was shot dead near his newspaper’s office May 15.] They have to think about how to protect themselves. But this doesn’t mean forgetting about our sources. They’re equal parts of the same conversation.

We also have to recognize the advantages we have as journalists–we have our publications, colleagues, and networks that support us. Sources often don’t have this. Many of our sources are people from humble backgrounds. They don’t have protection schemes and they may not be able to put their own situation of risk in perspective. It’s our responsibility to make sure they understand.

On the other hand, of course, we as journalists can’t be responsible for their protection in terms of physical measures or legal decisions–that’s the responsibility of the authorities. What we can do, though, is make sure our sources are informed.

This seems like an important distinction. Do you think there’s a broader societal obligation–for state institutions and non-governmental actors–to protect people who have spoken to the press as well?

Yes, it is an issue for society as a whole, but [journalists] have a greater responsibility. At the end of the day, it’s on us first and foremost. We have to recognize that there are ripple effects, our work has consequences for other people. We can’t change what’s already happened. We can’t offer a mother new children. But we can try not to cause any more harm.

I do believe there are strategies we can use to support one another. Really, we need something that’s more than a guide for responding to these situations. We can also coordinate with other sectors of society: human rights defenders, support networks, and other organizations that can help.

Journalists can face attacks, death threats, or risk being killed for their reporting. What are the consequences for sources? What dangers do they face for speaking to the press?

The mildest consequences are insults or harassment on social media. You could be fired–this has happened with some sources. We’ve seen workplace harassment, too. For example, if a police officer speaks to the press, he might not get promoted, or he’ll be sent to the worst, most remote police station, far from his family.

People get death threats–this has also happened to some of our sources, like Consuelo. She was a key source for our article on the massacre at San Blas. This woman had to flee from her home, even though it was a very public case, and she was a protected witness, she still had to flee, because in this country you’re threatened with death for speaking. Look at what happened to El Niño de Hollywood. He ended up getting killed. So, the consequences can be anything from harassment to death.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Miguel Ángel Tobar, known as El Niño de Hollywood, was a former member of the Hollywood clique of the Mara Salvatrucha gang turned witness for El Salvador’s Attorney General’s Office. Tobar’s testimony helped send an estimated 30 gang members to prison, according to El Faro.]

It’s not always possible to prevent this happening, but we can try to prevent it. The least we can do is try. What I think is completely inexcusable is to be naive, or fail to tell sources that something could happen. Instead, we should be saying, “We know it’s possible that this could happen,” and then talk about it.

That’s another important issue: you have to have established trust with the source. Trust between a journalist and sources is very important. As the journalist, you need to speak clearly and honestly with your sources, give them all the information and make sure they understand. This is how you build trust, and then you can have those difficult conversations … Without this foundation, as a journalist, you have nothing.

Why is the environment in El Salvador so dangerous for journalists and their sources?

I live in a country with the highest homicide rate in the world. We have what are called protected witnesses–people who were involved in committing a crime, they don’t serve a sentence in exchange for their testimony, and they receive protective measures. Often it’s not hard to find out who they are, though, so despite the measures, a lot of protected witnesses are still killed. And journalists can’t even provide sources with this kind of protection.

This is one reason why people are afraid to come forward: even if their identity will supposedly be protected, they can often be identified. This is why names are often withheld. But sometimes you have to say, “I can’t publish this,” even if it’s a very important story, because there’s just no way to ensure that person’s safety. I remember once, we were working on an article and we spent two hours with a source trying to figure out how to ensure they remained anonymous. It couldn’t be done, so in the end we decided there was no way to tell that story, even though it would be valuable to our readers.

What can journalists do to improve safety for them and their sources?

From my experience, there are two main things journalists should consider.

The first is the option to decide not to publish. It’s hard for us to say, “I’m not going to be able to publish this story or do it in the way that I want to,” but sometimes it’s the right choice. You can’t force a source to talk, and you can’t force them to put themselves in a position where they’re in greater danger. That’s their decision to make and we have to be able to accept that.

The second is that you have to be completely honest with your source. If you have decided to publish something, you should explain to them that their life may be in greater danger, they might have to take precautions to protect themselves and their families, they might even have to move. We can’t soften this, or try not to scare them–they need to understand the risk.

Martín Caparros, a well-known Argentine journalist, once said, “A journalist can be anything except naïve.”

We can’t be naive. As journalists, we have to think preemptively about what we can do and what could happen as a result. It’s not hypothetical–this is an action plan. We should have a list of resources on hand: they could help protect you, they could help get you out of the country, and so on. The key is it has to be well thought-out and clear beforehand, so we’re not trying to react after the fact. We need to be prepared, and help our sources be prepared as well.