“The current situation has made it necessary for the First Main Directorate (PGU) of [Russia’s] KGB to give the First Main Directorate of [Bulgaria’s] Ministry of Internal Affairs the following special means: devices for silent, mechanical ejection of special needles, containing swift poisons. …”

The above is an excerpt from Addendum 13 of the “Perspective plan for cooperation between the intelligence services of USSR and communist Bulgaria in the period 1972-1975”–a secret document made public thanks to Hristo Hristov, an investigative reporter with the Bulgarian independent daily Dnevnik who won a six-year-long legal battle for access to the secret archives of Bulgaria’s National Investigative Service (NRS), the country’s security agency. Last week, Hristov published his book The Double Life of Agent Piccadilly, based on more than 90 volumes of previously undisclosed NRS documents that shed light on the 1978 murder in London of Bulgarian dissident journalist Georgi Markov.

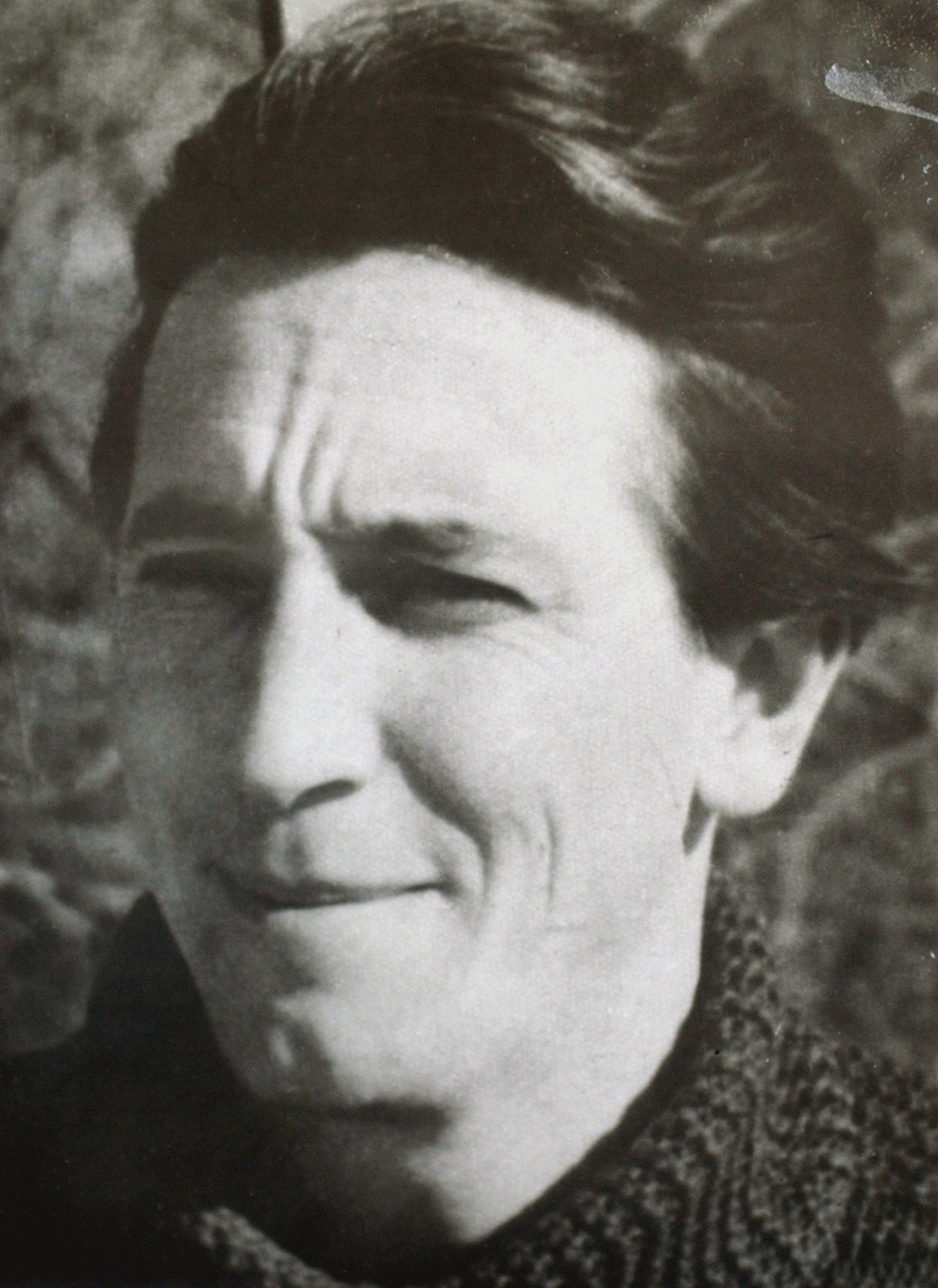

The “current situation,” as described in Addendum 13, refers to Markov’s critical BBC and Radio Liberty broadcasts against the communist regime of Bulgarian dictator Todor Zhivkov. Markov–a prominent writer and journalist–had defected to London in the late 1960s, but continued to energize the Bulgarian dissident community with his writings and radio commentary. Supporters thought of Markov as the Bulgarian Solzhenitsyn; the regime perceived him as the enemy whose activities justified the use of “special means” of elimination.

In September 1978, the means reached the end–Markov died in a London hospital of a mysterious flu-like illness, four days after being injected with the poison ricin, concentrated in a pellet doctors found in Markov’s body post-mortem. Markov told colleagues he remembered someone pricking him in the leg as he walked across Waterloo Bridge to work that day; when he turned to see who it was, he said he noticed a stranger picking up an umbrella from the ground. Since then, the ominous legend of the “Bulgarian umbrella” that was used as a murder weapon spread throughout Europe. It was widely believed that the assassin used the umbrella’s tip to inject the ricin pellet into Markov’s body. But Hristov argues in his book that the assassin used the umbrella not as weapon but as a distraction, and that the real weapon was a pen-like injection–the kind of device for “mechanical ejection of special needles, containing swift poisons,” described in Addendum 13.

Thirty years later, Bulgarian authorities decided to forego the statute of limitation on Markov’s case and keep the investigation open. As they should. The purported killer–Francesco Gullino, a Dane of Italian origin contracted for the job by the Bulgarian communist leadership under the code name “Piccadilly”–is still at large. So are the masterminds of the murder.

The investigation into Markov’s case, moreover, might illuminate more recent journalist poisonings in which Russian Security Service (FSB) involvement is suspected. (FSB is the successor to the KGB.) In July 2003, Yuri Shchekochikhin, the deputy editor of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, was overtaken by flu-like symptoms while on a business trip outside Moscow. When he returned, his condition worsened rapidly, leading to organ failure; several days later, Shchekochikhin was dead. Doctors said he developed a sudden “acute allergy” but could not find the cause. Shchekochikhin’s medical records were sealed, the case was buried. Colleagues believe he was poisoned to stop him from further uncovering an intricate, high-level corruption scheme.

A year later, Anna Politkovskaya fell ill and was hospitalized after drinking tea on a plane bound for the North Caucasus. Politkovskaya was en route to Beslan on September 1, 2004, to cover the hostage crisis at School No.1 that claimed the lives of more than 330 people–mostly children. She never reached her destination. Her colleagues at Novaya Gazeta believe she was poisoned. As in the case of Shchekochikhin, Politkovskaya’s medical tests were never disclosed. She survived that attempt on her life, but it was never investigated. Politkovskaya was later shot to death in October 2006.