After a vain search of local hospitals and mortuaries, the family of journalist Maneno Selanyika concluded their mourning rites on November 8 with prayer, but without a body. He was one of three journalists among hundreds or more Tanzanians killed during protests over a disputed election.

Selanyika was killed on the evening of October 29, Tanzania’s election day, near his home in the city of Dar es Salaam, according to the Dar City Press Club and Twaweza, a local civil society organization.

Two other journalists were killed:

- Master Tindwa Mtopa, a sports journalist with the privately owned Clouds Media, was at home in Dar es Salaam when he was shot, according to two journalists familiar with his case and the independent news outlet The Chanzo.

- Kelvin Lameck, who worked with Christian station Baraka FM, died in the southern city of Mbeya. A civil society statement said he was killed while “on duty.”

CPJ has yet to independently and fully confirm the circumstances surrounding the three journalists’ deaths and if they were linked to their work.

CPJ has not documented the fatal shooting of a Tanzanian journalist since 2012.

‘None of us expected it to be this bad’

The lack of clarity surrounding these killings echoes a broader murkiness about the days surrounding the elections as authorities suppressed protests, which escalated with President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s declared win with 98% of the vote.

Further protests are planned for independence day on December 9.

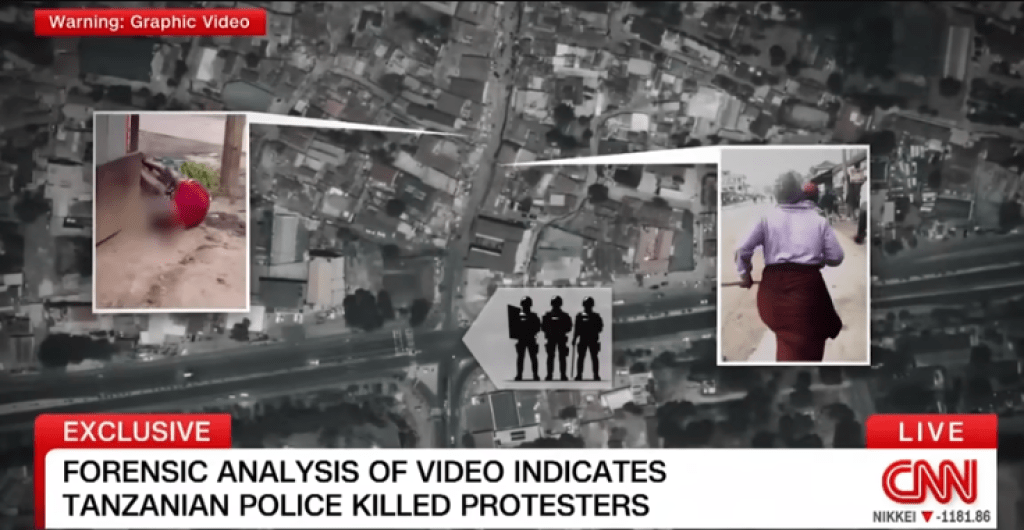

Different counts estimate that several hundred to 3,000 people died as the state responded to crowds of young demonstrators with deadly force amid a five-day internet blackout. Footage verified by the BBC and CNN showed bodies lying on the streets and piled up outside a hospital.

“The signs were there that things would be difficult during the elections, but none of us expected it to be this bad,” one veteran editor told CPJ.

Ahead of the vote, human rights groups warned of “deepening repression” and “terror” in Tanzania, with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and United Nations experts highlighting abductions, killings, and torture of opposition officials and critics. The main opposition party Chadema was banned from the election and its leader charged with treason.

There are signs that Tanzania tried to limit foreign press access during the polls, with at least three international outlets reporting to CPJ that their media accreditation applications were rejected. The Nairobi-based International Press Association Eastern Africa (IPAEA), which represents about 300 journalists regionally, told CPJ it was not aware of any successful applications to cover the elections on mainland Tanzania.

Charged with treason

CPJ spoke to at least 20 Tanzanian journalists, as well as several activists, who described a suffocating climate of fear of retaliation for speech perceived to question official narratives. The government refuses to provide an official death toll or respond to allegations of mass graves, while Samia has blamed foreigners for the protests.

“We cannot publish. I have a lot I want to write but I can’t,” one media owner told CPJ, explaining why his outlet had not reported on the journalists killed. Like most of those interviewed, he spoke on condition of anonymity, citing safety concerns.

“They will come to you and give you a treason charge if you publish,” he said.

Human rights lawyer Tito Magoti told CPJ that the media had largely failed to cover the elections comprehensively due to a combination of state control and the sector’s failure to exercise “boldness.”

“The media was absent in Tanzania during elections, if you call what happened on the 29th elections,” Magoti said. “Even now, as we speak, the media is missing, such that there is no reporting of what happened during elections, the atrocities that were committed, but also there are no critical voices from the communities coming out through the media.”

Constitutional and legal affairs minister, Juma Homera, said that 2,045 people were arrested over the election chaos. Among the detainees were prominent social media users and journalists, on charges that included treason, which carries a death penalty, incitement, and armed robbery.

At least one journalist, Godfrey Thomas Ng’omba, bureau chief with the online news outlet Ayo TV, was charged with treason. Ng’omba was arrested on election day, detained for six days, then rearrested. He was charged with treason and conspiracy to obstruct the elections on November 7, alongside 62 other co-defendants, according to court documents, reviewed by CPJ, which did not specify which actions amounted to the offenses.

Ng’omba was released on November 25, as authorities withdrew hundreds of charges, including for treason, following a presidential directive.

Accused of spying

Three journalists were arrested:

- On October 31, Kenyan journalist Shoka Juma was at the country’s coastal Horohoro border to report on stranded cargo trucks, when a group of plainclothes security personnel arrested him. Juma, a reporter with privately owned Nyota TV, told CPJ that the men held him at a police facility on the Tanzanian side of the border, asked him if he had been filming, and reviewed images on his phone.

“They were insisting that I was a spy,” Juma said. “I told them I came because I am concerned about the lives of the border people. But they accused me of incitement.”

He was released into the custody of Kenyan officials after about four hours, following public outcry and interventions by local advocacy groups Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI) and Vocal Africa. MUHURI activist and witness Francis Auma told CPJ that the plainclothes officers also tried to detain him but he ran away.

- On October 31, a broadcast reporter was arrested by men in military uniform in Dar es Salaam. The journalist, whom CPJ is not naming out of safety concerns, was found unconscious in a ditch the following day, minus his equipment.

- Alphonse Kusaga who runs the online media outlet Kusaga TV and reports for Arusha-based Sunrise Radio, was arrested on November 4 and released on bail the following day.

Muzzling online dissent before ballot day

Efforts to control the information flow began long before ballot day.

When Samia became president in 2021, following the death of John Pombe Magufuli, who was persistently hostile to the media, she initially adopted a progressive posture, lifting media bans. But her government continued to arrest journalists and shut down critical outlets, particularly targeting online dissent and eschewed an overhaul of problematic laws.

In January, the ministry of information required internet service providers to filter prohibited content when ordered to do so by the state, via an amendment to the Online Content Regulations, which already criminalized and censored speech on overly broad grounds.

In May, authorities blocked access to the social media platform X after the police’s account was hacked and used to falsely announce Samia’s death. Authorities later said X was blocked because it hosted pornography.

On October 20, the broadcast regulator on Tanzania’s semi-autonomous Zanzibar islands accused 11 online media outlets of operating without licenses. The Zanzibar Broadcasting Commission said three of the outlets, owned by the opposition ACT Wazalendo party, had been “found to broadcast content that incites hatred, provocation, and division” by airing a campaign speech by a senior party member.

ACT Wazalendo, whose leader was among those barred from running against Samia, denounced the move as “state-based censorship.”

One of the party’s leaders Janeth Rithe told CPJ that ACT Wazalendo had to start its own outlets because it was difficult to get airtime on mainstream media.

“A lot of media outlets in Tanzania have decided to be fearful because journalists are being targeted. They do what the ruling party wants. We are in slavery, slavery of the media,” said Rithe, who was arrested in June for telling supporters that the ruling party was running a police state.

Election observers from the African Union and the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) noted that media coverage in Tanzania favoured the Chama Cha Mapinduzi party, which has won every election since the restoration of multipartyism in 1992.

‘We don’t want to give people the pleasure of silencing us’

In the face of such pressure, some journalists fear they are losing public support by failing to tell the truth.

“We seem to be a bunch of unserious people who did no work during the elections and it is because of the behaviour of government institutions, squeezing us, threatening us in everything we wanted to do,” veteran editor Neville Meena said in a November public forum.

Khalifa Said, co-founder of The Chanzo, which has been documenting the post-election killings and abuses, told CPJ he will continue the painstaking work of shining a light on such atrocities.

“Hundreds of people took bullets. What kind of person, what kind of coward, would I be if I knew that and I was not willing to write an article with my name?” he asked.

“We don’t want to give people the pleasure of silencing us.”

CPJ’s emails requesting comment from the office of the government spokesperson, police, and Zanzibar Broadcasting Commission did not immediately receive responses. Chief government spokesperson Gerson Msigwa, Zanzibar Broadcasting Commission director general Ramadhani Bukini, and police spokesperson David Misime did not answer queries sent via messaging app.

Editor’s note: This text has been updated in the 20th paragraph to correct the number of co-accused to 62 and in the 27th paragraph to correct the description of Kusaga TV.