“CPJ Insider,” which was recently renamed from “CPJ Highlights,” is CPJ’s monthly newsletter that brings you behind-the-scenes updates on CPJ’s work around the world.

CPJ travels to Ecuador to meet with journalists, leaders

In March, a CPJ delegation traveled to Ecuador to meet with journalists, civil society groups, and government leaders and call for reform of the country’s communications law, one of the most repressive pieces of media legislation in the region.

Here, a Q&A with Natalie Southwick, CPJ’s South and Central Americas research associate, who set up the trip and participated in the mission:

Why was Ecuador a focus for CPJ?

CPJ has been advocating on behalf of journalists in Ecuador for years. In 2011, we published a report on press freedom under then President Rafael Correa, one of the most destructive leaders in the region in terms of a free press. Correa set the tone for other repressive countries. He led outrageous lawsuits against journalists, established ridiculous fines–he was very public in his disdain for the press.

His vice-president, Lenín Moreno, took office in May, and everyone expected he would continue this trend of Correismo. But we started to see this clear break with Correa’s legacy. Moreno was making changes–he was reaching out to journalists and he wasn’t using Ecuador’s abusive institutions in the same way.

So we sensed there was an opportunity. One of the main things for which we were advocating was reform to the country’s 2013 communications law, which was used to harass journalists and media outlets and establish patterns of self-censorship. That law is still on the books.

Who went with you and with whom did you meet?

The CPJ delegation consisted of Joel [Simon, CPJ’s executive director], John [Otis, CPJ’s Andes correspondent], and advisers Anya [Schiffrin, professor at Columbia University in New York and a member of CPJ’s Leadership Council] and Ricardo [Uceda, director of the Peruvian press freedom organization Instituto Prensa y Sociedad and a CPJ Americas Advisory Group member].

We met with a range of journalists, primarily from the few private media outlets that are left. We were in Guayaquil, where we spoke to journalists from El Universo, one of Correa’s primary targets. We also went to Quito, where we met with journalists from the daily El Comercio as well as from Teleamazonas and Ecuavisa, two private TV outlets that suffered harassment under Correa. We spoke to Janet Hinostroza, a TV reporter and CPJ’s 2013 International Press Freedom Award winner. Joel also appeared on her show.

You also had meetings with government officials. What were those like?

The delegation met with a lawmaker in Ecuador’s National Assembly, which has been involved in proposals to reform the communications law, and with individuals from the state media regulatory body CORDICOM. We also met with Andrés Michelena, Ecuador’s secretary of communication. Michelena was formerly an aide to Moreno, and, as far as we understand, they’re still very close. That was a good opportunity to get a read on what the president’s approach to press freedom may be.

When we presented our concerns and suggestions to him, Michelena made some commitments to us. He said the government would invite the special rapporteurs on freedom of expression of the United Nations David Kaye and of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Edison Lanza to visit and do an analysis of the press freedom environment and make some suggestions. Michelena said they expected to send the letters in a few weeks.

Michelena also said Moreno would consider making a speech on the importance of press freedom and clarifying his position toward the media, ideally for May 3, which is World Press Freedom Day. We’ll be following up to see how we can make sure that happens.

That’s a big deal. What’s next for CPJ on Ecuador?

We’re planning on publishing a special report on our findings. Stay tuned!

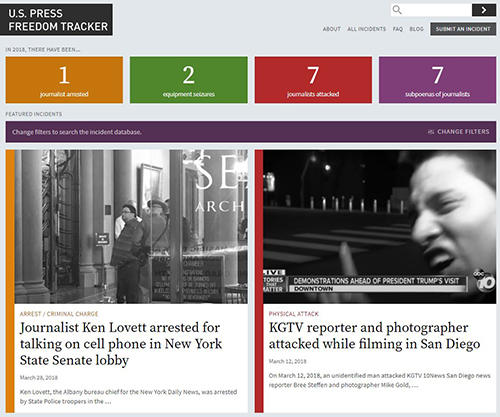

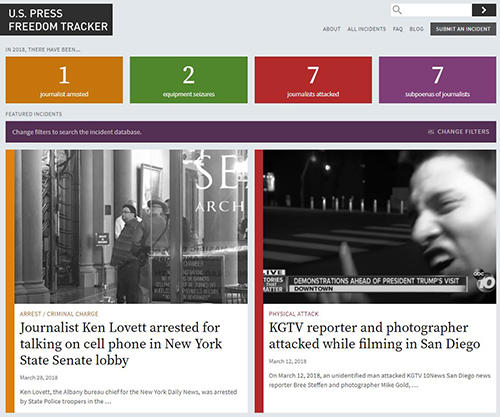

Press freedom incidents in the U.S. in March