When the news came that Greg Gianforte was making a $50,000 donation to the Committee to Protect Journalists it was 10 p.m. on the East Coast, but 8:30 a.m. in Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s Disney-like capital city, where members of our CPJ team were meeting officials to discuss that country’s punitive press laws.

At first, we were baffled. CPJ had had no contact whatsoever with the then-congressman-elect, and had criticized him harshly for body-slamming Guardian reporter Ben Jacobs and breaking his glasses. But as we read the Gianforte letter more carefully it became clear that the donation and public apology were part of a legal settlement, compelled by Jacobs and his lawyer. This was confirmed when we were able to reach Jacobs. CPJ accepted the donation based on this understanding.

For more than 35 years, CPJ has defended journalists around the world facing the threat of violence and legal action. That was why we were in Myanmar. At the same time, we have pushed leading democracies to uphold the highest standards of press freedom. We produced a critical report, “The Obama Administration and the Press,” examining Obama’s record of prosecuting leakers and withholding public information. We are acutely concerned by President Donald Trump’s hostile rhetoric toward the media and his threats to put journalists in jail. We have documented a series of physical threats, including the arrests of reporters covering the Standing Rock protests and the Trump inauguration in January, not to mention Gianforte’s body slam.

Since the beginning of the year, we have taken a number of actions to better uphold and defend press freedom in the U.S.–adding new research capacity and hiring a Washington Advocacy Manager. We have joined forces with leading press freedom organizations including the San Francisco-based Freedom of the Press Foundation to work on a project that will document every major press freedom incident that occurs in this country. We are calling it the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. Former Politico reporter Peter Sterne is leading the project, which is due to go live next month.

After I returned to New York from Myanmar, I called Trevor Timm, head of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, and asked if he thought we should use Gianforte’s compelled donation to underwrite the project. Timm liked the irony of using the settlement to ensure the systematic documentation of violations such as the one Gianforte committed.

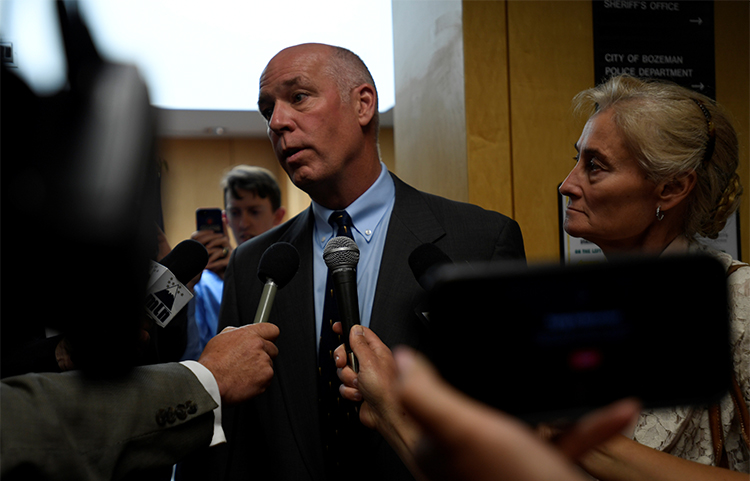

I also reached Jacobs on his cellphone in Montana, where he attended Gianforte’s criminal hearing. Jacobs supported using the funds to document press freedom incidents in the U.S. “This was a miserable experience that no one should have to go through,” Jacobs told me. “But if some good is to come of it, I am happy about it.”

Meanwhile, we have requested a meeting with now Congressman Gianforte to discuss our concerns about his behavior and to urge him to use his position in Congress to stand up for the rights of journalists not just in this country, but around the world. We know that the next time we are in back in Naypyidaw, or in some other part of the world where governments seek to intimidate and stifle critical reporters, we will face inevitable questions about the U.S.’s press freedom record. It will be tough to explain how someone who beat up a journalist is now a member of Congress.