From Cape Town to Lilongwe, four photographers on routine news assignments in major southern Africa cities were assaulted by security officials in the past two weeks. The details differ, but the heavy-handed actions in each case reflect a belief among those responsible for security that they are above the law and not publicly accountable. These recent attacks in southern Africa also highlight a wider phenomenon: Every day, somewhere in the world, news photographers are subjected to physical abuse by security and public officials who wish to suppress or control the powerful message delivered by images.

“Photographs provide incontrovertible proof. If there is no photographic evidence it’s easy to explain things away,” says Greg Marinovich, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer and co-author of The Bang-Bang Club, which detailed the work of photographers documenting violence in South Africa during the transition from apartheid. “There’s an audible noise when pictures are taken and a breaking of tension when the shutter is released. The subject understands when the picture is taken and I think officials have been told, ‘Don’t get yourself caught on camera.'”

In risky situations such as street protests or conflict zones, photographers and camera operators suffer disproportionate rates of fatality as documented by CPJ. Photographers and camera operators constitute more than 35 percent of journalist fatalities since the beginning of 2011, a period marked by large-scale civil unrest in the Arab world and conflict in the Middle East and South Asia.

But underlying the fatalities are instances of harassment, obstruction, and assault that photographers face every day in Africa and elsewhere. The recent southern Africa attacks all occurred in countries at peace, with functioning democratic institutions. In the most violent episode, on May 29, a private security guard fired rubber bullets at close range at The Star photographer Motshwari Mofokeng, who was photographing the eviction of people living in an empty Johannesburg factory. Such guards are routinely employed by provincial and local governments in South Africa to evict people occupying buildings or land illegally

Mofokeng, working with a reporter, was outside in a public place, covering a public issue. All seemed fine at first, until Mofokeng photographed security personnel chasing people. A guard turned his attention to Mofokeng, striking him and threatening to break his camera, the photographer told CPJ. In the subsequent melee, Mofokeng said, someone threw a stone at the guards and then a guard in a black uniform began firing. “The first shot was right at me. There were five or six shots after that: pah, pah, pah,” said Mofokeng, who was hit in the chest. He continued working, but later sought treatment at a local hospital and filed a complaint with police.

In an editorial, The Star editor Makhudu Sefara said the shooting was an attack on all citizens. “The truth is that media freedom is not a privilege for media practitioners, he wrote. “All of us, as freedom-cherishing South Africans, must realise that every time a journalist is klapped [hit], or shot, or killed, it is not merely about their publication or family, it is about all of us.”

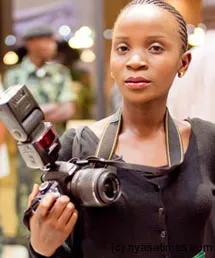

In Lilongwe, capital of Malawi, Nation photographer Thoko Chikondi was punched and manhandled by a security guard while taking images of a consumer rights activist delivering a petition to parliament on May 30. “Suddenly the chief security officer arrived and told the activist to get out of parliament,” Chikondi told CPJ.

“If the security guard had used force on the activist it would have made a good photo and I would have taken it, but that didn’t happen and so I didn’t take a picture of the security guard, only the activist,” she added.

“But within the blink of an eye,” said Chikondi, the guard grabbed at her camera and shouted that she had been photographing him without permission. “I held on to my camera trying to protect it and I was hit in the face. The guard hit me on my head with his hands.” Chikondi, who was treated at a local hospital for bruising, filed a complaint with police. Police later lodged an assault count against the security officer, who denied the charge in court this week. “I was lucky there was another photojournalist who took pictures of what was happening to me,” Chikondi said. “If not for those pictures, it would have been otherwise.”

In two separate episodes in Cape Town, photographers from the Cape Argus–a sister newspaper to The Star owned by the Independent Group–were roughed up and obstructed as they tried to cover the Department of Home Affairs’ treatment of refugees and asylum-seekers. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimates there are half a million refugees and asylum-seekers in South Africa, mostly from Zimbabwe, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

On May 22, photographer David Ritchie and reporter Yolisa Tswanya were interviewing family and friends of refugees who had been arrested for not carrying their identity documents and who had gathered outside the Caledon Square police station in central Cape Town. “As Dave lifted his camera, an official wearing a brown uniform spotted him,” Tswanya said. At first the journalists thought the individual was a prison official, but they later came to believe he was with Home Affairs. “He came over and told Dave to delete the photo. Dave refused, the official tried to take his camera, then grabbed Dave by the arm and dragged him into the police station courtyard. They wouldn’t allow me to go with him.”

The official deleted the pictures and returned the camera to Ritchie–who went back to the gathering and took more photos. The newspaper is considering both a civil and criminal complaint against the official.

The director-general of the national Department of Home Affairs told the Cape Argus that the agency had a policy of transparency and did not support the official’s behavior. The department’s manager for the Western Cape province said an investigator would look into the reported assault.

Five days later, Cape Argus freelance photographer Thomas Holder was taking pictures of hundreds of asylum-seekers waiting to renew their papers at the Refugee Reception Centre on Cape Town’s Foreshore.

When the gates to the center opened, Holder said, the crowd surged and staff turned a fire hose on the refugees. “I moved towards the gate with the crowd, never entering the premises, and shot more pictures closer to the gate of police and Mafoko Security staff pushing people out of the doorway of the centre and battling to close the gate,” Holder told Cape Argus reporter Kieran Legg.

Holder said a security guard directed him to stop taking pictures. When Holder refused, another guard grabbed him, pulled him into the reception center, and punched him in the chest. According to the Cape Argus report, the manager of Mafoko Security’s Cape Town branch, Newton Mathosa, called Holder’s report “implausible” because roughing up someone would have provoked the crowd.

Security personnel and public officials have long known–and often feared–the power of images. And today digital technology and social media have led to the exponential spread of documentary photography.

“Even in the time of Bang Bang (some two decades ago) people were wary of being documented because it could be used as part of cases, or evidence. And the more sophisticated were aware of how images could be used for propaganda,” Marinovich said. Referring to the spreading influence of documentary photography, he said: “Perhaps I see a difference now in the effect of photographs. There’s a trickle-up effect given the power of the picture to show what’s happened.”