Three Southeast Asian journalists–Cambodia’s Hang Chakra, Malaysia’s Zulkiflee Anwar Ul Haque, or Zunar, and Thailand’s Chiranuch Premchaiporn–were among the 48 awardees of the Hellman/Hammett grant, given to writers targeted with political persecution, who were recognized today by Human Rights Watch for their commitment to press freedom.

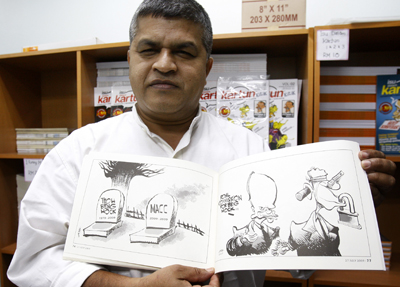

Hang Chakra, editor-in-chief of the daily Khmer Machas Rok, was imprisoned for 287 days on “disinformation” charges related to a story he wrote about high-level corruption. Zunar, a cartoonist and contributor to online news site Malaysiakini, now faces sedition charges and possible imprisonment for his banned political illustrations. Chiranuch faces a possible 50 years in prison on charges related to anonymous comments critical of the Thai monarchy posted to one of her news site’s Web boards.

I spoke on a panel with them today in Bangkok, where I described the repression they have faced and discussed how their individual cases are indicative of a downward trend in regional press freedom conditions. Excerpts from my address follow:

On behalf of CPJ, I would like to extend my hearty congratulations to these three recipients of the Hellman/Hammett awards, but underscore my organization’s belief that none of them should have suffered from the government harassment that is implicit in being a recipient of one of these prestigious awards.

These awards speak to the lack of progress in press freedom in three of Southeast Asia’s reputed democracies and point disturbingly to the closing of space that was once open for journalists to report and opine in Cambodia, Malaysia, and Thailand.

It is notable and chilling that two of today’s three recipients have been persecuted for their activities or journalism that originally appeared online. CPJ research shows that the region’s governments are increasingly targeting online journalists. Nearly half of the journalists jailed worldwide published their work predominantly online.

Chiranuch’s case, we believe, is meant to serve as a threatening example and warning to other online journalists, editors, and bloggers to censor themselves and refrain from reporting on taboo topics. Many Thailand-related blogs, our research has found, have as a result shut down their comment boards to avoid similar suits.

Chiranuch’s case has simultaneously underscored the arbitrary and vague ways Thai authorities have opted to enforce the Computer Crimes Act, legislation CPJ has identified as among the most punitive in the world from an Internet freedom perspective. Those inconsistencies, including the lack of institutional guidelines on what represents a violation of the act, have been laid bare in testimony given by Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Ministry officials in Chiranuch’s court case.

The Yingluck Shinawatra government in Thailand has an opportunity to set a new press freedom course, including by throwing out both the pending charges against Chiranuch and prioritizing the amendment of the Computer Crime Act’s vague provisions, particularly on third-party intermediary liability.

We note that the signals so far from Deputy Prime Minister Chalerm Yoobamrung and ICT Minister Anudit Nakornthap have been less than encouraging. Without moves to re-establish press freedom across Thailand’s political divide, Yingluck’s inaction will expose the bogus claims to democracy that her government’s affiliated street movement campaigned on while in the opposition.

In Malaysia, the government is taking back the online space it previously pledged not to censor. Our research shows the Malaysian government has backtracked on its vow to keep the Internet a censorship-free space.

Malaysiakini, a pioneering online news organization that has for over a decade pushed the boundaries of Malaysian journalism, has often featured Zunar’s political cartoons. CPJ views the harassment Zunar has suffered as a clear and present danger to both press and Internet freedom in Malaysia.

That authorities there continue to use antistate charges as outdated as the Official Secrets Act, the Sedition Act, and the Internal Security Act to undermine freedom of expression and threaten journalists like Zunar with imprisonment shows how far Malaysia has to go before it can claim to be a genuine and functioning democracy under the United Malays National Organization‘s rule.

In Cambodia, our view is that Hang Chakra was wrongly jailed for reporting on alleged government corruption and failing to disclose his sources. Cambodia’s government purports to support a free press and points to the explicit laws in Cambodia’s law books protecting press freedom–laws that authorities frequently circumvent to stifle criticism.

The reality on the ground is that Cambodia’s media is dominated by newspapers sympathetic to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party, and those that refuse to step in line–such as Hang Chakra’s Khmer Machas Rok–are often targeted for harassment by his government. Along those lines, we continue to campaign on the unresolved death of Cambodian journalist Khem Sambo, who reported critically about Hun Sen’s government and was murdered just weeks before the 2008 general elections.

All three of these journalists honored here today have effectively been punished for their courage to speak journalistic truth to power in their respective countries. Their courage in reporting is an inspiration to all of us who believe democracies cannot function without a free and probing press. Their repression raises uncomfortable questions about the quality of democracy in their respective homelands.

May the governments who have bid to make punitive examples of their courage in reporting take note of the international recognition and prestige they have received here today.