Today we released our annual census of imprisoned journalists around the world, citing 145 reporters, editors, and photojournalists behind bars on December 1, an increase of nine from 2009 figures. The tally begs the question, What’s in a number?

Cuban journalists Normando Hernández González and José Luis Garcia Paneque know all too well the significance and weight of this number. On March 18, 2003, Cuba’s state security forces carried out a three-day countrywide raid and arrested 29 journalists in the crackdown, González and Paneque were among those detained. Cuba’s so-called “Black Spring” had begun. Their crime was practicing independent journalism in a country where control of the media and brutal enforcement of censorship are absolute.

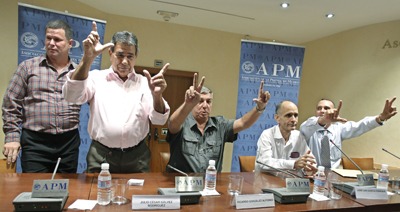

In response, CPJ obtained a license from the U.S. Treasury allowing us to provide urgent financial assistance to the imprisoned journalists’ families to help them pay for food, medicine and travel expenses to visit the remote locations of the prisons where their loved ones were held. CPJ also provided a list of imprisoned journalists to the Spanish Foreign Ministry to ensure that those named would be part of any negotiations for the release of jailed Cuban dissidents. In 2010, the Spanish government and the Cuban Catholic Church negotiated a deal with Cuba, which agreed to release all imprisoned journalists rounded up in 2003. To date, 17 have been released, with the majority resettled in Spain.

Three from the 2003 crackdown remain behind bars, as does one other Cuban journalist.

In an ongoing CPJ series of first-person stories by freed Cuban journalists, Normando Hernández González gives a graphic account of the horrors of his experience behind bars: “I long to forget, but cannot, to erase from my memory the murmurs of suffering, the plaintive screams of torture, the screeching bars,” he writes. “I detest having my hands handcuffed behind my back and attached to my feet, also handcuffed, and lying for hours on my side on the cold, damp cell floor while insects and rodents walk all over my garroted body being tortured with the technique known in prison slang as ‘Little Chair.’ I want to sleep without enduring the pain caused by a rubber cane or tonfa used to bruise or break my skin.”

Again, what’s in a number? In the case of Canadian-Iranian journalist Maziar Bahari, one of dozens of journalists imprisoned in Iran, there was arbitrary arrest then 118 days of incommunicado detention and torture. His crime? Simply being a journalist. Without the efforts of CPJ and other press freedom organizations, Bahari may well have served out a 13-year sentence handed down by a Teheran Revolutionary Court delivered to the journalist in absentia in May 2010. “I know my jailers in Iran were aware of the depths of international concern,” said Bahari.

International attention has an impact both in pressuring governments to release journalists imprisoned around the world and in providing direct assistance to families that are often impoverished with the loss of the sole breadwinner’s income. CPJ provides assistance for food and medicine, as well as resources for legal counsel, appeals, and petitions for amnesty.

In Azerbaijan, Emin Fatullayev, the father of imprisoned Azerbaijani journalist Eynulla Fatullayev, says he has been threatened with death if he does not stop speaking out about his son. An anonymous caller telephoned his Baku home on March 17 and said he and his son must “shut up once and for all,” or “the entire family will be destroyed.” Eynulla Fatullayev and his family have endured harassment, physical attacks, and death threats, none of which have been adequately investigated by the police.

Iran and China, with 34 imprisoned journalists apiece, tie for the world’s worst jailers of the press. CPJ is working to win the release of each journalist that is part of the outrageous number that is 145. Where that is not yet possible, we are seeking to provide urgent care and support for the families of imprisoned journalists.

In 2010, CPJ helped to secure the release of at least 46 imprisoned journalists around the world. Please give your support to journalists and their families by ensuring that they receive adequate medical, legal, and financial assistance to meet their needs while unjustly behind bars. In the words of Maziar Bahari, “raise an outcry” for the release of journalists in Iran and worldwide.

Here are some ways you can get involved:

- Donate to CPJ’s distress fund for journalists. The fund provides emergency grants to journalists facing persecution for their work.

- Help sponsor the family of a journalist imprisoned for his work. When a journalist is jailed, his or her family is often left destitute. A little support can have a large impact on these shattered lives.

- Let us know if you have pro-bono services you can offer.

- Contact us if you plan to travel to countries where journalists are imprisoned or attacked. You can volunteer to help local journalists.

- Publicize the plights of journalists facing persecution around the world. If you would like to interview, book a speaking engagement, or publish work by a journalist assisted by CPJ, contact the Journalist Assistance program.

CPJ is grateful to the Ford Foundation and to Molly Bingham for supporting our campaign to win the release of journalists imprisoned around the world.