To request a printed copy of this report, e-mail [email protected].

1. Summary

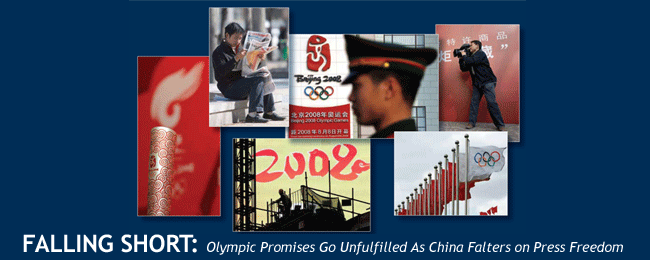

China jails journalists, imposes vast censorship, and allows harassment, attacks, and threats to occur with impunity. It has failed to meet its Olympic promises to provide media freedom.

The Committee to Protect Journalists prepared this report in 2007, updating and reissuing it this year, to illustrate the yawning gap between China’s poor press freedom record and the promises made in 2001 when Beijing was awarded the Olympic Games. The International Olympic Committee awarded the 2008 Games to the Chinese capital based on assurances that authorities would allow the media “complete freedom,” and that they would apply “no restrictions” to coverage. The government did ease restrictions on foreign journalists in January 2007—but failed to adhere to the liberalized rules during March unrest involving Tibet. Chinese journalists are in jail. Vast censorship rules are in place. Harassment, attacks, and threats occur with impunity. China has fallen short in its pledge to the international community. It should do much more to honor its promises and to foster a truly free press. Here is an overview:

Domestic Censorship in Full Force

Domestic censorship remains in force across all regions and types of media, operating at a particularly high level since October 2007. All news outlets are subject to orders from the Central Propaganda Department. Provincial officials cooperate with their counterparts in other regions to shut down coverage of sensitive local issues.

Journalists face blanket coverage bans. They must avoid stories about the military, ethnic conflict, religion (particularly the outlawed spiritual movement Falun Gong), and the internal workings of the party and government. Coverage directives are issued regularly on matters large and small. Authorities close publications and reassign personnel as penalties for violating censorship orders.

By law, all news outlets must be overseen by some state body, which in turn is responsible for ensuring that party propaganda orders are followed. At the national level, the Xinhua News Agency, China Radio International, China Central Television, the Guangming Daily, and the People’s Daily are under the control of central government and party leadership. Provincial and municipal authorities oversee regional and local newspapers and television stations.

Chinese Media, Past and Present

Starting in 1979, the Chinese media enjoyed a general revitalization, with serious efforts made to safeguard press freedom and to protect journalists. That trend was abruptly reversed when the government cracked down on pro-democracy demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

While Communist Party “guidance” of the news remained tight after 1989, media were swept up in the country’s economic growth. The result: media conglomerates with party and government ties, producing modern, commercially savvy products for an increasingly sophisticated audience.

The salary system for journalists is a principal means of regulating content. Reporters are paid a low base salary, supplemented by bonuses when articles are published. Reporters typically pursue stories sure to make it into print or broadcast, reporting them in a way that will satisfy the censors. In awarding pay, many news outlets also apply a ratings system that judges the political merits of a reporter’s coverage.

Journalists say these controls are effective at quashing investigative reporting in the state-controlled media. Despite the restrictive climate, many Chinese reporters pursue difficult stories and post their work on blogs or online message boards.

Threats to Chinese Journalists

At least 26 journalists are in Chinese prisons as a direct result of their work, most of them on vague antistate charges. These cases typically involve reporting and commentary that promote democracy or embarrass party leaders. China is the world’s leading jailer of journalists, a notorious distinction it has held for nine consecutive years.

Violent attacks on the press, though uncommon in Beijing, occur with frequency in the rest of the country. Local officials and businesspeople suppress coverage by using brute force, hiring thugs to threaten or attack journalists. These local figures also use civil defamation lawsuits to silence critical coverage. Since the local courts do the bidding of local party bosses, such cases are usually decided against journalists. Truth is not a defense.

Chinese journalists do not have the right to organize to protect their interests. The officially sanctioned All-China Journalists Association has failed to address their needs, and Chinese journalists lack an official venue to recommend reforms.

Controlling Cyberspace

China’s efforts to control the Internet have met with success, but its many thousands of censors are struggling to stay ahead of its Web-using citizens. An estimated 210 million people are online in China, and subscription rates are rising at double-digit rates.

Internet censorship is both technological and regulatory. The government demands that individual service providers monitor content. These providers filter searches, block Web sites, delete content, and monitor e-mail traffic. A study of China’s e-mail filtering system conducted by the Internet censorship research organization OpenNet Initiative found that messages with politically offensive subject lines or text had been blocked.

International service providers have proved susceptible to Chinese government pressure. Yahoo turned over e-mail account information that led to the arrest and imprisonment of a journalist and several dissidents. Microsoft came under fire for deleting a well-regarded reporter’s blog. And Google launched a self-censoring Chinese search engine.

Risks and Rules for Foreign Reporters

In January 2007, the government introduced temporary regulations that were supposed to allow foreign correspondents the freedom to travel without government permission and to interview anyone who consents. The liberalized rules are due to expire in October 2008.

Government officials have not adhered to the relaxed regulations. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China has recorded more than 230 cases of harassment, obstruction, and detention since the rules were adopted. Many of the complaints came when the looser regulations were put to their first real test: coverage of the ethnic demonstrations that led to rioting in the Tibet Autonomous Region in March. Foreign journalists were barred from Tibet and from three neighboring provinces where protests were being staged.

In official statements, the government alleged an anti-China bias in foreign news coverage, stoking national pride and anger at outsiders in the press. At least 10 foreign correspondents reported receiving anonymous death threats; numerous other Western journalists said they had received harassing phone calls, e-mails, and text messages.

Foreign news organizations are instructed to hire local assistants through authorized service organizations only. Sources and assistants remain vulnerable to government pressure. Chinese citizens who speak to the media about sensitive issues or help reporters cover such matters can be subject to reprisal.

» continue to Chapter 2:

Words and Deeds: Confronting the Contradictions