To request a printed copy of this report, e-mail [email protected].

2. Words and Deeds: Confronting the Contradictions

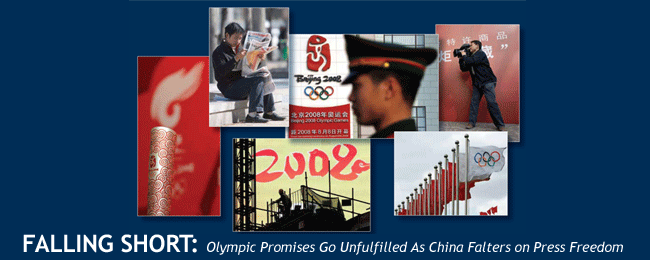

As part of the Olympic bid process, Beijing pledged complete freedom for all accredited journalists. Yet as the Games are set to begin, China has fallen far short in allowing free and unfettered news coverage.

Seven years ago, when Chinese officials filed their official bid to host the 2008 Olympics, they made a crucial promise. “There will be no restrictions on media,” the Beijing organizers said, an assurance that helped them win the Games and one that they repeated frequently in the months and years that followed.

Yet China has failed to meet its obligation as judged by international press freedom standards: More than two dozen journalists are jailed for their work. Domestic media remain tightly controlled by the state. Internet censorship is more elaborate than ever. Foreign media are heavily obstructed.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has been remiss in confronting Beijing on its unfulfilled promises, although China’s failure was not always a given. Many journalists were optimistic, in fact, when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs eased restrictions on foreign media in January 2007. The new rules said foreign reporters could travel without government permission and could interview anyone who would speak with them. But the relaxed regulations crumbled when put to their first test: coverage of the ethnic demonstrations that led to rioting in Tibet in March 2008.

As soon as antigovernment demonstrations broke out, foreign journalists were expelled from Lhasa, capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Foreign travel to the Himalayan region was cut off after peaceful pro-independence demonstrations escalated into clashes with security forces and Han Chinese migrants. As the crisis grew, the government expanded its obstruction of foreign media into the neighboring provinces of Gansu, Qinghai, and Sichuan. In the six weeks after the March 14 crackdown in Tibet, more than 50 foreign journalists were obstructed while trying to report on the unrest. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) said its members had been “detained, prevented from conducting interviews, searched, and subjected to the confiscation or destruction of reporting materials. Authorities have intimidated Chinese sources and staff, and in some cases ordered them to inform on foreign correspondents’ activities.”

WHAT THEY SAID

“There will be no restrictions on journalists in reporting on the Olympic Games.”

Foreign news reports on the unrest, from sources as diverse as CNN and YouTube, were blocked within the country. Domestic news outlets, which are controlled by the state, carried reports from the official Xinhua News Agency, which played up nationalist themes and described the demonstrators as “separatists” who threatened the country’s unity. In official statements, the government alleged an anti-China bias in foreign news coverage, stoking both national pride and anger at outsiders in the press. A nationalist campaign raged online as Chinese pointed to inaccuracies in news coverage as evidence of a bigoted foreign press. At least 10 foreign reporters received death threats, according to the FCCC, while CPJ and other rights organizations saw their e-mail systems come under cyber-attack.

The situation was sharply at odds with the 2008 Olympic slogan, “One World, One Dream.” Conditions deteriorated so severely by late April that FCCC President Melinda Liu, Beijing bureau chief for Newsweek, felt compelled to say that “the reporting interference and hate campaigns targeting international media may poison the pre-Games atmosphere for foreign journalists.”

Back in 2001, the IOC was also reviewing bids from Istanbul, Osaka, Paris, and Toronto to host the Games. But China, ascendant as a world economic power, and its leaders, seemingly eager to create a more open society, made a powerful argument that Beijing deserved this international showcase. To quell concerns over China’s repressive media practices, the IOC’s evaluation commission, in a report issued on April 3, 2001, cited the government’s promise that “there will be no restrictions on media reporting and movement of journalists up to and including the Olympic Games.”

During the IOC’s deliberations, Chinese officials repeated this commitment to press freedom and other human rights. “By allowing Beijing to host the Games you will help the development of human rights,” Liu Jingmin, vice president of the Beijing bid committee, told Agence France-Presse in an April 2001 interview. “China and the outside world need to integrate. China’s opening up is irreversible.” Others offered broad assurances. “We will give the media complete freedom to report when they come to China,” Wang Wei, secretary-general of the Beijing bid committee, told reporters the day before China was awarded the Games in July 2001.

These were encouraging words—and credible ones given that China’s media universe had been expanding for more than a decade, driven by commercialization and the demands of an increasingly sophisticated readership. Many Chinese reporters, then and now, have pursued stories in a competitive atmosphere similar to that faced by reporters worldwide.

But the state continues to oversee all news outlets—and the Central Propaganda Department has stepped up censorship when tested by sensitive events. In the days before the important 17th Communist Party Congress in October 2007, authorities imposed such strict content requirements that the major dailies all used the same Xinhua political stories with the same headlines. Security agents shut Internet data centers that hosted even a single Web site considered politically offensive. Tens of thousands of Web sites were affected during that time.

Over all, Internet censorship is so extensive that in February, the government boasted that it had removed more than 200 million “harmful” online items during the prior year. Web sites that have not been established by an official news outlet such as a newspaper or broadcaster are barred from posting their own news or commentary. By law, they may only reproduce material that has passed through censors at approved media organizations.

China continues to hold 26 journalists behind bars, more than any country in the world. The cases have many common elements: Eighteen of these journalists are jailed for their online work, and 20 are being held on vague antistate charges such as subversion. In case after case, authorities have punished reporters for exploring issues that might embarrass the government or challenge its public officials. But one trend stands apart: Two-thirds of these journalists were imprisoned after China made its 2001 promise to free the media.

The detainees include Lü Gengsong, a freelancer jailed in August 2007 for “inciting subversion” in online articles that detailed government corruption and organized crime. Zhang Lin, a political essayist, was imprisoned in January 2005 after writing about unemployed workers and official scandals. Zhang Jianhong was jailed in September 2006 for an online commentary that decried the recurrence of human rights and press freedom violations in the run-up to the Games. He called the situation “Olympicgate.”

How did the IOC allow this to happen? At times, IOC officials have been ambivalent about the importance of press freedom at the Games and their own obligation to enforce the commitments made by China. “In this country there are laws and they have to be respected—that is something we have to accept and everybody has to accept,” Hein Verbruggen, head of the IOC’s coordination commission for the Beijing Games, told reporters at a May 2006 press conference in Beijing. “As long as the media behaves in the normal way, then I’m sure there will be no problems. … If it’s in the law, then it is in the law.”

Concerned by such statements, CPJ met with IOC Olympic Games Executive Director Gilbert Felli and his staff at their headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, in November 2006. CPJ board member Jane Kramer urged IOC officials to take a strong position on press freedom because the Olympics stand for principles of open exchange and transparency.

The meeting was unpromising. “It is not within our mandate to act as an agent for concerned groups,” Felli told CPJ. “Journalists are imprisoned all over the world, sometimes for good reasons, sometimes for bad reasons.” While the IOC representatives said that they would consider CPJ’s press freedom concerns, their subsequent statements were equivocal.

At a press conference in April 2007, Verbruggen, pressed on the broader question of China’s human rights offenses, repeated the IOC’s stock response that the Games would bring “positive change” to China. IOC President Jacques Rogge said the Games are “a force for good wherever they are staged”—a vague formulation the committee stuck to whenever media issues were raised.

Only recently—after the clampdown on Tibetan coverage—has IOC leadership expressed serious concern about the press situation. At an April 10, 2008, press conference with foreign correspondents in Beijing, Rogge called on China to live up to its “moral engagement” to improve human rights and provide greater media freedom. “We will do our best to have this be realized,” he said, referring to the regulations that were supposed to grant foreign reporters the freedom to travel throughout the country. “It is very easy with hindsight to criticize the decision” to award the Games to Beijing, he added.

Tepid though it was, Rogge’s admonition drew a strong government response. A Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said her government expected the IOC to adhere to “the Olympic charter of not bringing in any irrelevant political factors.” In effect, Chinese officials were now dismissing their own promise of greater press freedom as a political irrelevancy.

China’s media policies were tested again within weeks by two disasters—one resulting from human error, the other from natural causes. In April, authorities restricted foreign media and tightly controlled domestic reporting after two trains collided in Shandong province, killing 70 and injuring hundreds. Coverage of the May 12 Sichuan earthquake, which killed thousands and left many more homeless, was far less restricted as Chinese reporters broadcast live from the quake area and foreign journalists were given wide access. The nature of the events appeared to affect the coverage controls. The train accident betrayed a flaw in the transportation system—officials failed to relay information about track construction—while the quake offered an opportunity to show leaders responding aggressively to citizen needs.

So what should visiting journalists expect when they come to China? Veteran foreign correspondents, for example, assume that their phone may be tapped and their e-mail scanned. They know they run the risk of confrontation if they look too closely at issues such as the military, Taiwanese independence, pro-democracy activists, AIDS villages, the banned Falun Gong religious movement, or underground churches that meet without the government’s permission. Advocacy groups report heightened government surveillance of pro-Tibet, pro-democracy, and religious groups in the run-up to the Games.

Experienced Chinese journalists know the limits of their freedom; not one journalist interviewed by CPJ plans to break new ground while the Games are being held. But thousands of young, inexperienced Chinese will be hired by foreign media as production assistants, translators, runners, and drivers for the Games. Foreign journalists should realize that their Chinese counterparts face potential risk if they arrange sensitive interviews or reporting trips.

Visiting journalists should also understand the realities of reporting in China. For those who venture beyond the sports venues to capture a wider view of China, a different and far more restrictive set of rules applies. If non-Olympic events suddenly become newsworthy—as events in Tibet did in March—every journalist should be prepared to work in an environment that has been traditionally unfriendly and sometimes hostile to the media, no matter how glittering the Games appear.

» continue to Chapter 3:

Commerce and Control: The Media’s Evolution