To request a printed copy of this report, e-mail [email protected].

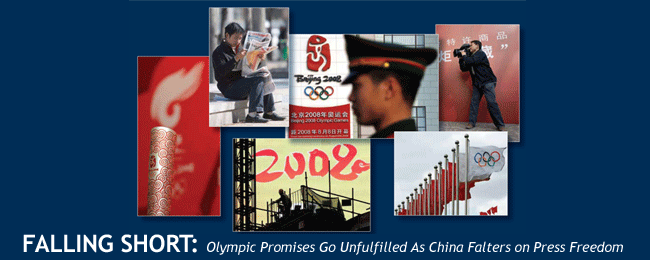

4. Inwardly Restricted: Domestic Repression Remains

Despite Beijing’s promises, restrictions on the domestic press have tightened in the years leading up to the Olympic Games. The administration of President Hu Jintao uses administrative measures, ideological mandates, and punitive actions such as imprisonment.

In July 2001, crowds rushed into the streets of Beijing in celebration. The Chinese capital’s massive advertising campaign in support of its bid to host the Summer Olympic Games in 2008 had resonated deeply among its citizens. The International Olympic Committee’s decision, telecast live from Moscow, brought a flood of collective joy—even the police dispatched to control the crowds couldn’t keep themselves from grinning.

If you asked a Beijinger then about the Olympics, you were likely to hear the word kaifang, or open. Open to reform, open to change, open to competition, and open to joining the international community. The last time that so many people had flooded the streets may well have been during the protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989. For the few whose memories weren’t dulled by time and censorship, the events there had come to symbolize the closing of possibility. In 2001, well into a transformative economic boom that would lead to its accession to the World Trade Organization, China seemed poised to open its arms to the world. Seven years later, in the place of real change for the Chinese public, an expression of frustration has settled in. Wai song nei jin. Outwardly relaxed, inwardly restricted.

China’s domestic press situation is a paradox. In an increasingly rich media environment, ordinary people transmit their digital recordings of news events before censors have time to act, bloggers argue against the Communist Party line, and commercial news outlets compete for readers. At the same time, the administration of President Hu Jintao has boosted efforts to keep the news under its control through administrative measures and party-driven ideological mandates, hiring and firing heads of news outlets and jailing journalists. Chinese reporters face more threats than their foreign colleagues at the local level, where government officials and businesses hire thugs to quiet negative coverage.

Physical attacks against journalists occur regularly. In January, as many as 30 men attacked a journalist with the Hong Kong-based Ta Kung Bao as he was photographing forced evictions in Wuhan, China’s central Hubei province, Radio Free Asia reported. Last year saw a high number of serious work-related attacks. In January 2007, a Nanfang Daily journalist was hospitalized after five unidentified men attacked him outside his home. The next month, a group of men beat two Guangxi cameramen and seized their cameras as the journalists tried to report on workers’ efforts to get back wages. And in August 2007, a local agriculture official and his staff assaulted five reporters as they conducted interviews with relatives of the victims of a deadly bridge collapse in Hunan province.

As alarming as these assaults have been, however, official repression in the form of arrests, censorship, and demotions has had more lasting and wide-ranging effect. When Guangzhou’s Nanfang Dushi Bao (Southern Metropolis News) took on the role of public watchdog, for example, it got a bitter taste of government retribution. In 2004, three of its staff members were jailed after the paper reported the death of a young college graduate in police custody. The exposé forced the government to change national laws for detention and custody, but the story also prompted bureaucrats to lash out at the messengers. Editor-in-Chief Cheng Yizhong was detained for five months. Former Editor Li Minying spent three years in jail before being released in 2007. And General Manager Yu Huafeng was freed in February after serving four years on trumped-up corruption charges.

AN EDITOR’S VIEW: TUNNELING THROUGH STONE

“The censorship system has never undergone substantive change, even if its methods have become more nuanced and concealed. But in spite of this fact, change is unavoidable”

The jailings of Nanfang Dushi Bao staff illustrate the prevailing tension in the Chinese media. The popular commercial newspaper has genuine sway; its exposés and editorials have informed its readers, changed laws, and transformed the consciousness of the Chinese public more than any foreign news outlet could do. But the imprisonment of its staff members—two of whom, Li and Yu, were not even involved in the reporting of sensitive stories—stand as a warning to those who would offend powerful Communist Party officials.

In June 2006, a brief Xinhua News Agency report announced that Beijing Vice Mayor Liu Zhihua, who oversaw building for the Olympics, had been removed from his post for “corruption and dissoluteness.” The dispatch did not provide information about the specific wrongdoings of which Liu was accused, and Chinese party-run and commercial newspapers were ordered to carry only the official report. Though commercial papers outside of Beijing drew attention to the news with large headlines and additional information culled from official Web sites, Chinese journalists were forbidden from conducting their own interviews or investigations into the case.

The accusation of corruption raised serious questions about the 300 billion yuan (US$40 billion) allocated for construction and infrastructure development in Beijing ahead of the Games. International Olympic Committee representatives assured reporters that they had been told the case was unrelated to Olympics construction. But even foreign reporters faced a wall of silence when they attempted to investigate the case.

“Anything involving construction or development for the Olympics involves high-level officials,” said Charles Hutzler, an Associated Press journalist who reported extensively on the city’s preparations for the Games. “It’s impenetrable.”

Like other sensitive or forbidden topics in Chinese media, bad publicity in the Liu Zhihua case could pose a potential threat to the political power of the top Communist Party leadership. At its heart, the aim of the propaganda machine in China is to preserve the hegemony of those in power, and any restriction on reporting can be traced back to this objective. Along the way, a flurry of crucial information has been lost, hidden, or unexamined.

Li Datong, former chief editor of the progressive China Youth Daily supplement Freezing Point, said the last decade has seen far too many important issues go unreported until too late: corruption within the Politburo; AIDS transmission in Henan caused by official greed and missteps; huge and potentially catastrophic mistakes in the building of the Three Gorges Dam; and the ambitious and costly South-to-North Water Diversion Project—approved in 2002, it has yet to deliver a drop of potable water to Beijing.

Journalists are forced to tread carefully on issues of major public interest, or lose their jobs. Li himself became a vocal critic of official control over the media after he was demoted from his editorial position in 2006.

The level of risk facing individual writers, intellectuals, and journalists is a function of personal connections, professional status, and the tone and context of his or her critique. Direct criticism of national leadership or the current system of governance is sure to bring trouble, but the extent varies. Beijing University law professor He Weifang, who has written frequent editorials for newspapers such as Xin Jing Bao (Beijing News), has not been able to publish his writings since April 2006, when his calls for multiparty reform and his praise of the Taiwanese model of democracy, made during a closed government meeting, became public. But, protected by his employers and his reputation, He continues to teach classes, post his writings in a blog (one that is occasionally deleted by its hosting service), and speak to the foreign media.

Writers without such protection face more severe consequences. In these ranks are people like Yang Tianshui, a dissident writer who spent the entire decade of the 1990s in prison on a charge of “counterrevolution.” After his release, he became a frequent contributor to the banned U.S.-based Web sites Boxun News and Dajiyuan (Epoch Times), the latter an outlet that authorities particularly revile for its connection with the anti-Communist spiritual movement Falun Gong. Yang came under surveillance by state security agents in connection with his work and was frequently detained. In 2005, a group of overseas Chinese elected him (without his knowledge, he said) as “secretariat” of a fictional “democratic Chinese transitional government” in a fantasy online exercise. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison on charges of “subverting state power.”

For writers like Yang with a history of activism or a perceived connection to anti-Communist groups, authorities seem to read criticism of the party as a call to action. The merciless punishments in these cases reflect the ruling party’s mandate to suppress any organized opposition.

Daily journalists are less likely to face prison because they are blanketed by layers of censorship. Party-run news outlets must please their masters at local and central party committees, and content is under the oversight of an in-house official hierarchy. At commercial news outlets, where editors may steer clear of straight propaganda in an attempt to solicit increasingly discerning audiences, a mandatory affiliation with a state agency nonetheless forestalls complete independence. No specific orders need to be given to journalists to remind them not to offend the Communist Party leadership, and matters of greater nuance are handled by communiqués from local propaganda departments to the relevant officials connected to each outlet.

“The government doesn’t want to harm journalists,” said Li, the former Freezing Point editor. “It controls them.”

In the nearly 30 years that have passed since Deng Xiaoping initiated economic reform in China, there have been many occasions to hope for press freedom. Commercialization, technology, and an apparent desire by the public for more and better information have pushed the press to be increasingly liberal and consumer-friendly. But each sign of a door’s opening seems to trigger the instinctive slamming of it by Beijing authorities.

While the scope of topics available to Chinese media consumers today is greater than in the past, criticism of the national leadership remains a largely unchallenged taboo. In this aspect, the media has yet to reach the level of serious political debate with which it engaged the public in the 1980s, the early years of reform that some journalists still see as a golden age for the press.

The Tiananmen Square crackdown was the turning point for the press, and even those journalists who merely covered the events there were condemned and “re-educated.” A 1993 CPJ publication, Don’t Force Us to Lie: The Struggle of Chinese Journalists in the Reform Era, documented the demoralizing process of re-education that faced the journalists not jailed or relocated after 1989. In that book, a China Daily journalist described the aftermath of the crackdown: “Writing self-criticisms. Attending a lot of meetings to read aloud my self-criticisms so other people could criticize my self-criticisms. Really terrible.”

In the 1990s, central authorities reimagined the news media as a commercially viable entity tied financially and legally to the government and the Communist Party. The contradictory forces of this new arrangement seemed to come to a head in the SARS crisis.

At the end of 2002, a deadly pneumonia-like virus spread quietly throughout southern China. It was months before the Ministry of Health made its first report about SARS, and another two weeks before Guangzhou media reported it. Coverage was then shut down by orders of the Central Propaganda Department. In the early months of 2003, Chinese authorities systematically covered up new cases of the virus before vocal international concern at the global spread of SARS prompted a change in policy.

For a moment, the freshly installed administration of President Hu seemed to take this lesson to heart. Health Minister Zhang Wenkang was sacked along with several other high-level officials, including the mayor of Beijing, and the government pledged to boost transparency. In the spring of 2003, one former newspaper editor told CPJ, “We realized that we could break the rules.” Despite propaganda department orders to play down the spread of SARS, the Chinese press sent reporters into hospitals and reported new cases of the disease. The moves by Hu and Premier Wen Jiabao to penalize officials responsible for the cover-up encouraged hopes for media reform.

The opening was short-lived. “There was a three-month spring,” said He, the Beijing University professor, “but it wasn’t followed by summer. It went straight to winter.” President Hu, still an enigmatic figure both in and out of China, proved disappointing to those who had him pegged as a reformist. The next five years saw increased restrictions on the press, the prosecution of several high-profile journalists, and a string of progressive editors removed from their posts.

One of the chief ways that authorities have limited investigative reporting during Hu’s tenure is empowering provincial officials to cooperate with their counterparts in other regions to block coverage of sensitive local issues. For years, each local propaganda department minded only its own media, allowing reporters from outside the region to parachute in and do some real reporting. But now, through the support of the party’s Central Committee, the lines of communication between officials in each region have opened—and the reporting opportunities have closed. There is now less of what reporters call yidi jiandu, or cross-territorial reporting, which had become a common way for commercial news outlets to keep their stories interesting without angering authorities in their home region.

In addition, provincial and city-level officials often collude with local businesses to suppress potentially embarrassing information. Ideology becomes a stick used by businesses to protect their own commercial interests; propaganda authorities are easily influenced by businessmen who claim that critical reports will threaten stability. As an increasingly common line of defense for public figures and corporations, civil libel cases against media outlets and journalists have created a further disincentive to critical reporting. These cases are usually decided against the press, according to separate research by professor Benjamin Liebman at Columbia University Law School and professor Chen Zhiwu of the Yale School of Management.

Here is a line you are unlikely to read in a Chinese newspaper today: Full press freedom will only follow serious political reform. As long as the party’s department of propaganda has authority over media content, journalists will not be free or safe. As long as the government maintains the right to decide who can publish or broadcast news to a mass audience, the press will always have strict limits. And without an independent judiciary, journalists will remain at risk of arrest and prosecution in connection with their reporting.

Public debate over press conditions in China stops at the point of mentioning the underlying political causes. Up to that point, the press has been vocal in defending its rights to report the news safely and without interference. The domestic media’s interest in their own working conditions was illustrated last year by two very different cases. The first involved a well-known reporter for a state-run news outlet who had just been released after eight years in jail. The second, which occurred in the same coal-mining province of Shanxi, involved a young man bludgeoned to death in a case that raised questions about the ethics of the Chinese press.

Gao Qinrong, an established reporter for the official Xinhua News Agency, was imprisoned in 1998 after doing what any good investigative journalist is supposed to do. Suspecting that something was awry in the construction of a costly public irrigation project in his home province, he discovered that not one of the thousands of tanks was connected to a water source. Xinhua wouldn’t publish his report, but it ended up in the internal edition of the People’s Daily, which is distributed to high-ranking party members only. It wasn’t long, however, before other news outlets had caught on to the extraordinary scoop, and national TV cameras flocked to cover the corruption scandal.

Local authorities held Gao responsible for the embarrassment, and he was sentenced to 12 years in prison on charges that included fraud, pimping, and embezzlement. Gao spent eight of those years in jail and was finally released in December 2006.

Gao went to the media, giving interview after interview to domestic and international news outlets describing his ordeal and calling for his conviction to be vacated. The regional Chinese newspapers Nanfang Zhoumo (Southern Weekend) and Nanfang Dushi Bao published lengthy interviews with Gao in which he described his reporting, his imprisonment, and his efforts to get the charges dismissed. By the time the Central Propaganda Department acted to shut down coverage of the case, Gao had again become national news, a high-profile example of what seemed to be the worst fate that could befall an enterprising journalist in China. CPJ honored Gao in 2007 with its International Press Freedom Award.

A few weeks after Gao’s release, another Shanxi media employee was in the news. This one, a young man named Lan Chengzhang, was a former coal miner who had been working for a Beijing-based newspaper for just a few days when he was killed. Chinese news reports on his death debated whether or not to call Lan a journalist; like many reporters, he didn’t hold official journalist accreditation. Too, when he arrived at the site of an illegal coal mine, Lan may have been looking for what dozens of other reporters, accredited or not, had also been seeking: hush money from an owner of a mine that should not have been operating. Men hired by the mine boss brutally beat him in full view of a colleague.

The case sparked public outrage, and President Hu called for an investigation. Six men were quickly brought to trial and convicted. It remains unclear whether Lan was soliciting a bribe.

Chinese media used these two cases as a platform to draw attention to their own rights. Gao was presented as a hero, a journalist whose dedication to the truth had stolen him from his wife and young daughter. The press presented his attempt to restore his name as a fight for justice. In the coverage of Lan, the news articles debating his status as a journalist clearly placed a premium on this distinction. Obviously, his killing was wrong. If he was a journalist, then his killing indicates something larger—an obstruction of the right and duty of the press to seek and publicize the truth. If he was not a journalist, or if he was an unethical one, then his death takes on a much different meaning.

Together, coverage of these two cases points to an awareness among the domestic media about their circumstances, their obligations to the public, and their limitations. Yet Chinese journalists are unable to speak in concert.

Unlike foreign reporters in China, who presented a united case to the International Olympic Committee and the Foreign Ministry for improving their working conditions in the run-up to the Games, mainland Chinese journalists do not have the right to organize independently. The official All-China Journalists Association has failed to address their needs, and Chinese journalists lack an official venue for making specific recommendations for reform. The press has so far been unable to take advantage of the hosting of the Olympic Games to further its own right to report the news.

Political reform—however likely or unlikely it is in the long run—will not happen before the opening ceremony on August 8. But China could make significant improvements in press conditions by reforming its libel laws to allow for criticism of public figures, by narrowing the terms of national security legislation, and by ensuring that local officials who punish journalists for their reporting are held accountable.

» continue to Chapter 5:

Censorship at Work: The Newsroom in China