Burma’s military junta imposed tighter internet restrictions after the Saffron Revolution. But news continues to flow thanks to the exile-run media and their resilient undercover reporters.

Posted May 7, 2008

RANGOON, Burma

When Burmese troops opened fire on unarmed demonstrators here last September, marking the violent culmination of weeks of pro-democracy protests, the Norway-based Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) had 30 undercover reporters on the streets. Despite the military government’s strict coverage bans, the journalists used the Internet to transmit news reports and images to DVB, which disseminated the information globally. The reporting, some of which was rebroadcast by major international media outlets such as CNN and Al-Jazeera, provided the world with disturbing and iconic images of the unrest, which came to be known as the Saffron Revolution. Burmese authorities, seeing these uncensored pictures leak through their tightly controlled borders, shut down the Internet altogether at the height of their brutal crackdown, which resulted in the detentions of nearly 3,000 people and the deaths of at least 31 others.

Since then, Burma’s military junta has applied additional pressure and imposed new restrictions to prevent news reports from being transmitted via the Internet. Five DVB reporters are still jailed and another five cannot be accounted for, according to Moe Aye, news editor for the satellite television and radio broadcaster. “We don’t know many of their fates,” Moe Aye said from DVB’s regional office in Chiang Mai, Thailand. “We fear they are paying the price for their courage.”

Yet exile-run news organizations and their in-country, undercover reporters have proved surprisingly resilient, a CPJ investigation has found. Savvy undercover journalists have continued to find ways around government-administered firewalls through the use of proxy servers and other tactics, CPJ found after observing conditions here and interviewing editors in the exile news media. Editors say their news organizations are reporting stories from inside the country as quickly as ever. And a review of recent coverage-including reports on the devastating May cyclone that struck southwestern Burma-shows that the quantity and depth of in-country reporting has remained consistent or improved since the crackdown.

Take Mizzima, a New Delhi-based, exile-run news agency that saw its unique daily readership more than double, to 15,000, since last year’s crisis. Mizzima lost contact with several reporters after the crackdown, but Editor-in-Chief Soe Myint said the agency emerged stronger from the experience because it forced editors to better coordinate and systematize news gathering. Some in-country reporters, for example, have received training in Internet safety and encryption techniques, Soe Myint told CPJ in a telephone interview.

“The new Internet restrictions haven’t so far had much effect on our daily work,” he said, adding that editors and reporters have established a system to convey news even if the government should unplug the Internet again. Soe Myint declined to discuss details but is confident that “we are prepared for the worst-case scenario.” With renewed international interest in Burma-related news, he said, Mizzima has expanded its in-country reporting network since the Saffron Revolution.

Mizzima’s assessment is shared by other exile media outlets. Aung Zaw, editor and founder of the Irrawaddy news Web site and newsmagazine, said that his reporters continue to send news from Internet cafés every day. In late February, for instance, undercover reporters transmitted video footage of a massive fire in the central Burmese city of Mandalay, which editors were able to post on the Irrawaddy Web site just hours after the blaze began. In March, its monthly magazine published a detailed cover story that highlighted-and even mocked-the government’s attempts to censor the Internet.

Mizzima’s assessment is shared by other exile media outlets. Aung Zaw, editor and founder of the Irrawaddy news Web site and newsmagazine, said that his reporters continue to send news from Internet cafés every day. In late February, for instance, undercover reporters transmitted video footage of a massive fire in the central Burmese city of Mandalay, which editors were able to post on the Irrawaddy Web site just hours after the blaze began. In March, its monthly magazine published a detailed cover story that highlighted-and even mocked-the government’s attempts to censor the Internet.

In recent weeks, Irrawaddy‘s online edition has broken a number of stories about new government restrictions, including heightened surveillance of student groups in the run-up to the national referendum on a new constitution in May.

Exile-run media groups also challenged official accounts of the May 2-3 cyclone that ravaged the country, leaving tens of thousands dead and missing and as many as 1 million homeless. The government initially said only 350 people were killed and, in the aftermath, state-run broadcast media flooded the air with images of Prime Minister Maj. Gen. Thein Sein holding government meetings, consoling dislocated villagers, and surveying the storm’s damage.

Mizzima, for one, offered readers a more critical assessment of the government’s response, which its on-the-ground reporters found to be sorely lacking in several disaster-hit areas. Amid widespread electricity blackouts and extensive telecommunication damage, Mizzima reporters made use of satellite phones to send images and information out of the country, Soe Myint said.

“The difference between our news and the government’s news was that we were able to provide eyewitness accounts,” Soe Myint said. “That’s something the government never does.” Mizzima, citing unnamed government and international aid officials, reported casualty figures much higher than the government’s official count, which itself eventually rose into the tens of thousands.

The Irrawaddy ran critical commentary on the government’s initial reluctance to allow foreign aid workers into the country. “The government made [storm] announcements and newspapers ran the story on pages four or five of their editions,” Aung Zaw said. “If they had treated the story like they should have-like we did, as front page news-there’s no telling how many lives could have been saved.” Aung Zaw said the storm coverage reinforced his belief that “the information we are receiving now is arguably better than ever before… Despite the culture of fear and intimidation, we are receiving more and more applications from lots of twentysomethings who say they want to do something useful and are willing to take the risks to become our reporters.”

Many found inspiration in the street protests that began in August 2007 after a government policy shift caused fuel prices to spike. As the antigovernment movement gained momentum, Buddhist monks came to lead tens of thousands into the streets to call more broadly for democratic change. State censors banned local media from reporting on the demonstrations-but striking images of aggrieved robe-wearing monks, transmitted out of the country by undercover journalists, captivated global news audiences.

On the afternoon of September 27, Burma’s military government struck back, closing all connections to the Internet (a shutdown that lasted four days), blocking journalists’ mobile telephone signals, and ordering soldiers to open fire on demonstrators. Japanese news photographer Kenji Nagai, shot at point-blank range by a Burmese soldier, was among the victims. Despite the government’s censorship efforts, the shocking murder was captured on video and disseminated worldwide.

The same day, Irrawaddy‘s Web site was hit by a debilitating virus that caused the site to crash for four days. The news organization later found that the virus was written in Russian script and sent via an Internet protocol address based in Panama. Aung Zaw told CPJ that while “it was not 100 percent clear” that the Burmese government had launched the viral attack, the timing seemed “more than coincidental.” To guard against future cyberattacks, he has changed Irrawaddy‘s Web host and established a new backup site in case of emergencies.

Most exile-run news outlets have their roots in political opposition groups. While some have maintained those ties, others have professionalized their operations with the help of public and private donors such as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the Canada Fund, and the Open Society Institute.

These news organizations fill the critical news gap left by Burma’s tightly controlled domestic media. Well before last year’s crackdown, CPJ had designated Burma as one of the world’s most censored countries. Local newspapers are heavily censored by state authorities before publication, while the broadcast media is wholly monopolized and manipulated by the military. Journalists who have tested the regime’s near-zero tolerance for media criticism have often ended up in prison. Burma is a perennial leader in jailing journalists, according to CPJ’s annual surveys.

That censorship regime includes government-administered blocks on accessing the World Wide Web and popular internationally hosted e-mail services such as Yahoo and Google’s Gmail. OpenNet Initiative, a research project on Internet censorship conducted jointly by Harvard University and the universities of Toronto, Oxford, and Cambridge, found Burma’s Internet controls among the “most extensive” in the world in 2005.

OpenNet said that Burma’s government, through its influence and control over the country’s two Internet service providers, “maintains the capability to conduct surveillance of communication methods such as e-mail, and to block users from viewing Web sites of political opposition groups [and] organizations working for democratic change in Burma.” Blocks continue to be maintained on the most prominent exile-run media outlets, including DVB, Mizzima, and Irrawaddy.

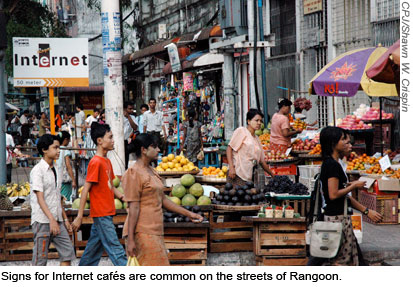

Even so, there are large technological holes in the junta’s firewall. Because of the exorbitant costs and restrictions on direct home access, nearly all Burmese citizens access the Internet in privately run cybercafés, which in recent years have proliferated in Rangoon and a handful of other major cities.

Even so, there are large technological holes in the junta’s firewall. Because of the exorbitant costs and restrictions on direct home access, nearly all Burmese citizens access the Internet in privately run cybercafés, which in recent years have proliferated in Rangoon and a handful of other major cities.

Those cafés were the main conduit for the news and information that was sent out to exile media groups during the Saffron Revolution. The government has since tried to tighten the screws on café owners, mostly through intimidation and heightened surveillance. The effort also includes new requirements that Internet cafés post signs warning their customers that accessing restricted materials is a crime punishable by imprisonment.

One Internet café administrator who spoke to CPJ on condition of anonymity said police officials told him that he would be held personally responsible for what his customers viewed. Editors for exile media say that certain cafés now check the contents of patrons’ memory sticks before allowing them to plug into computers.

DVB’s Moe Aye said police recently pressured an Internet café administrator in Rangoon to provide assistance in tracking and identifying a customer-one of DVB’s undercover reporters-who sent messages and video clips over the Internet to Oslo, Norway, where DVB’s main news office is based.

“Some cafés that wouldn’t cooperate [with authorities] have been closed down,” said Moe Aye, citing information from his reporters. The Burmese government is known to be particularly sensitive to DVB’s often critical broadcasts, which are beamed by satellite from London around the world and into Burma. As many as 1 million Burmese have satellite dishes, according to news reports.

CPJ research conducted several months before the 2007 unrest found that Internet café administrators often helped patrons bypass government firewalls to connect to the World Wide Web, usually through proxy servers hosted in foreign countries. One popular proxy server at the time was gLite, which allowed surfers to circumvent government blocks on Gmail. Certain versions of gLite were shut down at the height of the Saffron Revolution, according to the site’s India-based administrator.

Yet the government pressure has not stopped users from getting around the firewall. All nine current versions of gLite were accessible across a wide cross-section of Rangoon’s cybercafés when CPJ conducted its latest research trip in March. The site’s administrator said gLite attracts more than 100 new users every day. And his site is just one of a wide array of proxy servers in use in Rangoon’s cafés, CPJ found. “Users are just as creative as ever in circumventing government firewalls,” the gLite administrator said.

Burma’s cybercafés are still filled with young users who regularly bypass the state-censored print media and instead access global news sources online, CPJ found in March. This researcher saw dozens of Internet café patrons visit forbidden news sources such as the BBC and Al-Jazeera. Just as popular were critical blogs, which publish in the Burmese language and post foreign news stories critical of the government.

One prominent blogger, the pseudonymous Niknayman, posted a story on Blogspot urging Burmese citizens to vote against the proposed constitution, while Myochitmyanmar, another blogger, posted a wire service report about the military junta’s recruitment of children to fight in the ongoing conflict with ethnic insurgent groups.

In all but one of the 15 cafés visited, CPJ was able to access numerous sites that the government had officially blocked, including DVB, Mizzima, Irrawaddy, and video-sharing sites such as YouTube and Metacafe. One café posted a list of its most visited Web sites, which included five internationally hosted proxy sites, the banned e-mail service providers Yahoo! and Gmail, and the forbidden online chat forum GTalk.

The list was posted next to the government’s warning against accessing restricted materials.

That doesn’t mean that dissident surfing is safe, of course, particularly for in-country bloggers. Nay Phone Latt, a blogger who posted material critical of the junta on his Web site, was detained on January 29 while patronizing an Internet café. He was being held at Insein Prison in spring.

Why Burma’s reclusive regime continues to allow Internet users and undercover reporters to defy its restrictions is unclear. Bertil Lintner, a well-known author of books on Burmese politics who recently researched a critical survey of Burma’s media, contends that the junta still lacks the technological competence to effectively and efficiently police the Internet.

Lintner notes that other authoritarian countries devote considerably more resources to enforce Internet restrictions. In China, cybercafé owners are required to install network monitoring equipment and turn over to the authorities any patrons who access restricted materials. In Vietnam, cafés are equipped with video cameras and monitored by secret police.

To effectively censor the Internet, Lintner said, Burmese officials “have to use more technology like China or more manpower like Vietnam. From what we’ve seen so far, it seems they’re incapable of doing either and can only resort to threats and intimidation.” At the same time, Lintner argues, the authorities cannot shut down the Internet altogether because the politically influential business community has become reliant on cybercafés for cheap overseas communication.

Irrawaddy’s Aung Zaw believes that the junta’s surveillance capabilities were diminished by an October 2004 purge of military intelligence officials, many of whom had been trained in monitoring techniques in Russia.

These openings offer promise, but they also present risk. While relatively few Burmese citizens regularly see news from exile media, politically active university-age citizens are actively surfing the Internet and encountering these reports. Aung Zaw and his colleagues are wary of being overconfident. Aung Zaw said some in-country reporters fear that the current climate is all a ruse—that authorities have created a false sense of security so they can identify and eventually apprehend undercover journalists.

Those fears are driving Burma’s undercover reporters to become more innovative. DVB’s Moe Aye said his in-country reporters now check in with editors by pay phone at predetermined times to mitigate the risk of communicating on lines that may be tapped by authorities.

In-country journalists have their own clandestine procedures. One undercover DVB reporter secretly reported on the trial of a popular political prisoner by using his mobile telephone to record the detainee entering the courthouse. Later that day, he used the Internet to transmit the footage in time to meet DVB’s production deadline.

“They say, ‘Don’t ask me how, just wait and it will be there.’” Moe Aye said. “I don’t ask, so I can’t tell you how they do it. They have their own ways.”

Shawn W. Crispin is CPJ’s Bangkok-based Asia program consultant.